[Warning: The following contains spoilers for Watchmen, The Outer Limits, and some old sci-fi you probably weren’t planning on reading.]

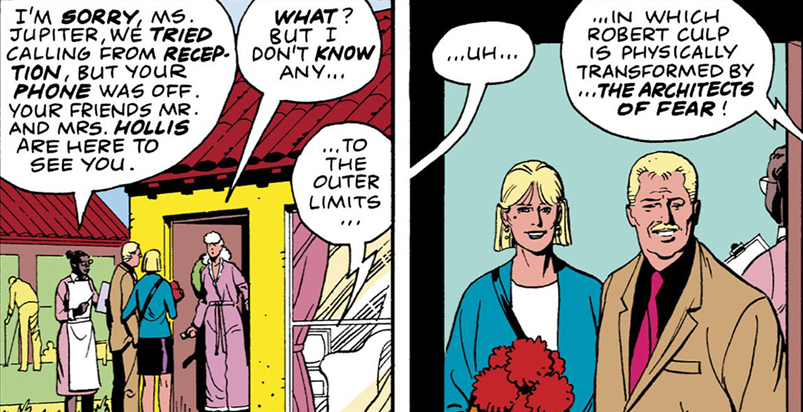

At the end of Watchmen, a television set in the background announces a rerun of The Outer Limits episode “The Architects Of Fear.” This was a reference to a creative debate that occurred behind the scenes between writer Alan Moore and editor Len Wein. In their own words:

“Around issue 10, I came across a guide to cult television. There was an Outer Limits episode called ”The Architects of Fear.” I thought: ”Wow. That’s a bit close to our story.’ In the last issue, we have a TV promoting that Outer Limits episode — a belated nod.”

—Alan Moore (Entertainment Weekly, 2009)

“I kept telling him, ‘Be more original, Alan, you’ve got the capability, do something different, not something that’s already been done!’ And he didn’t seem to care enough to do that.”

—Len Wein (Wizard, 2004)

The book Alan Moore was looking at was likely Cult TV: A Viewer’s Guide To The Shows America Can’t Live Without!! by John Javna, published in 1985. This is an educated guess based on it being the only book on the topic I could find that existed in the late ’80s. Its section on The Outer Limits contains a list of “Classic Episodes,” with “The Architects Of Fear” appearing as #1. The brief episode summary describes it as:

Robert Culp, a scientist, is selected by idealistic cronies to frighten the nations of Earth into united against a common enemy. The plan: he’ll be transformed into a monster, land a flying saucer at the U.N., and threateningly announce he is from the planet Theta. Instead, the saucer crashes off course, and he’s shot by a bunch of hunters. Innovative and startling special effects.”

“A bit close” is a good way to describe the first two sentences. However, all it takes is a casual viewing of the episode (which was difficult in the pre-internet days) to see just how dramatically different from Watchmen the story really is.

“The Architects Of Fear” is really about the lead character’s emotional struggle as he loses both his marriage and his humanity. A full 40 minutes of this 50 minute episode are devoted to his coming to grips leaving his wife, and his slow and terrible transformation into a monster. The faked alien invasion is merely an excuse to explore this drama and horror, with the twist being that the stunt ultimately fails. Compare to Watchmen, where the stunt is the twist.

The reason the stunt fails is that instead of landing at the U.N. as planned, the ship goes out of control and lands in the woods. Our monster encounters three hunters, who it tries to intimidate by disintegrating their vehicle with a lab-supplied ray gun. One of the hunters shoots the monster, who somehow manages to limp back to the lab without being seen by any other bystanders — except for his wife, who snuck into the lab based on a feeling.

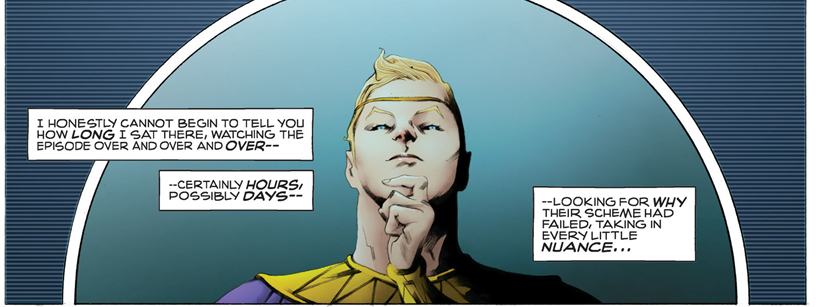

Instead of creating a worldwide frenzy, it results in three hunters having a wild tale that no one else will ever believe. This makes Len Wein’s Before Watchmen: Ozymandius that much more grating, because it makes this supposed genius out to be a complete nincompoop when he watches the same episode for research:

Dude, it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to see why they failed.

But debating the finer details of The Outer Limits is ultimately a moot point, because it turns out there was an even earlier story that is much closer to Watchmen, though it still doesn’t involve a giant squid.

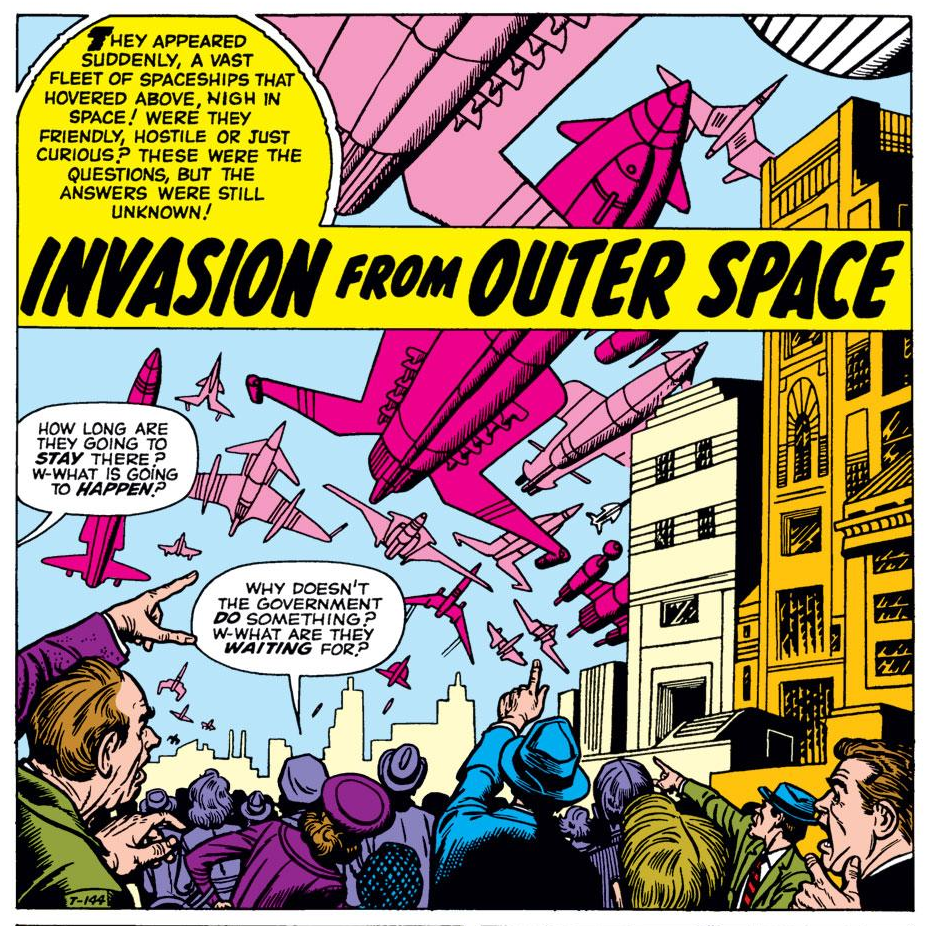

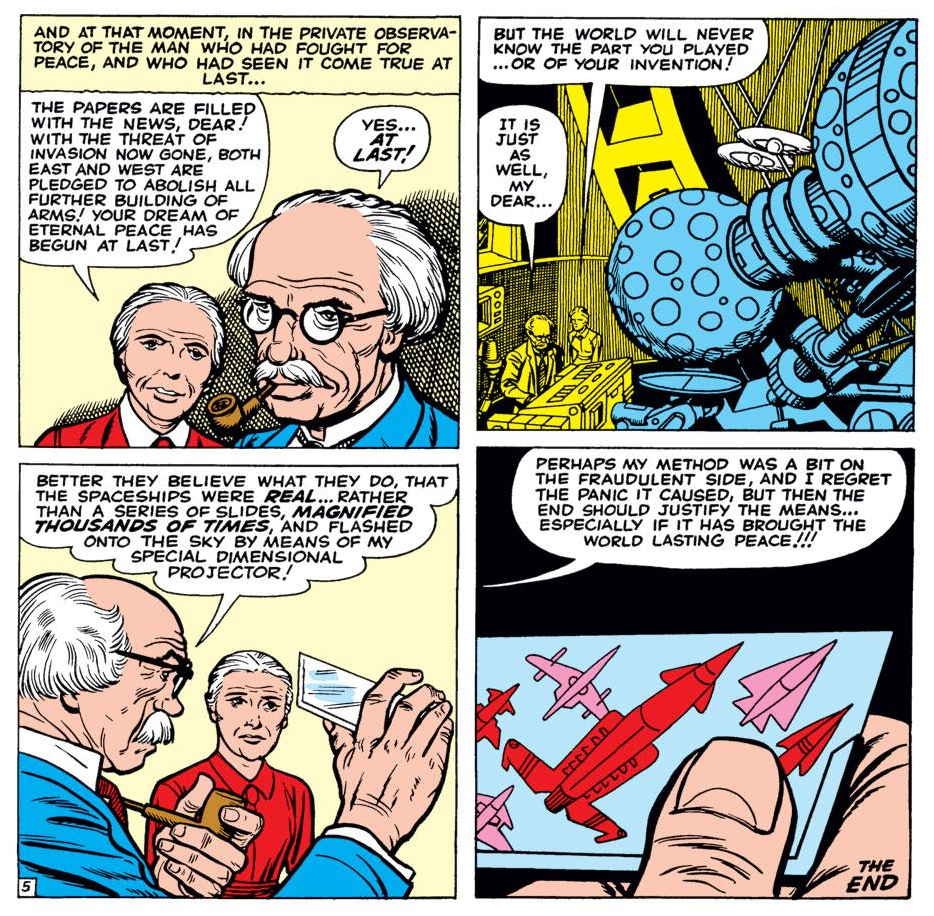

“Invasion From Outer Space” was the lead story in Tales Of Suspense #2. It was published in 1959, four years before “The Architects Of Fear.”

The story is uncredited, but most scholars agree that it was drawn by Jack Kirby and inked by Christopher Rule. No one is positive who wrote it, but it’s unlikely to have been Stan Lee, who signed his name to every story he scripted. I’m no expert on identifying writing styles, but I did notice that nearly every caption ended with an ellipses, which was a quirk of Jack Kirby scripted stories at the time.

The story starts with an alien invasion that has united the world’s leaders against a common threat. Initially they try to bomb the ships out of the sky, but when their weapons have no effect, they decide the only option is to dismantle their armory in order to demonstrate that they are peaceful. Once everything has been dismantled, the ships go away. The twist, of course, is that a scientist has faked the entire thing.

Being such a huge Jack Kirby fan, is it possible Alan Moore read this story at some point and simply forgot about it? Or for that matter, could “The Architects Of Fear” writer Meyer Dolinksy have read it?

A creator forgetting they encountered an idea elsewhere isn’t an uncommon phenomenon, especially in the music world. Paul McCartney has a famous story about how while writing “Yesterday,” he became paranoid that he might’ve accidentally nicked it from somewhere. After playing it for just about everyone he knew and no one saying they recognized it, he felt confident that it was completely original.

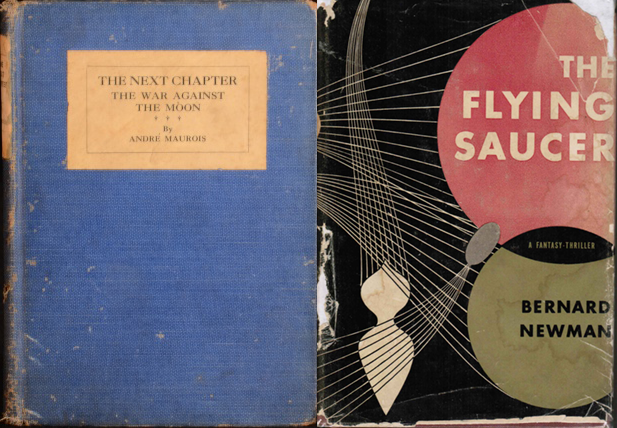

But hold the phone! Even this wasn’t the first story to use the concept of faking an invasion to trigger world peace. Bernard Newman’s The Flying Saucer was released in the UK in 1948, just a year after the term “flying saucer” was coined. The story is about — guess what? — faking the existence of aliens to unite the world against a common threat.

And it doesn’t end there! André Maurois’ 1927 French novel The Next Chapter: The War Against The Moon (translated to English in 1928) also shares the same premise, though in a crazy twist it turns out there really is a threat on the moon, and a scientist who creates a death ray to shoot at the fictional threat from Earth ends up angering the actual threat, who fire back with their own death rays. Whoops.

I’m sure it goes even further back than that, but my point is that no one was particularly stealing from anybody, any more so than Edge Of Tomorrow stole from Groundhog Day (which itself was not the first story to use a time-loop story device).

The Flying Saucer also quoted a line from an actual speech given at a United Nations conference in 1947, in which British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden said: “Sometimes I think the people of this distracted planet will never really get together until they find someone in Mars to get mad against.” Bringing everything full circle, President Ronald Reagan openly shared a similar sentiment around the time that Watchmen was being serialized.

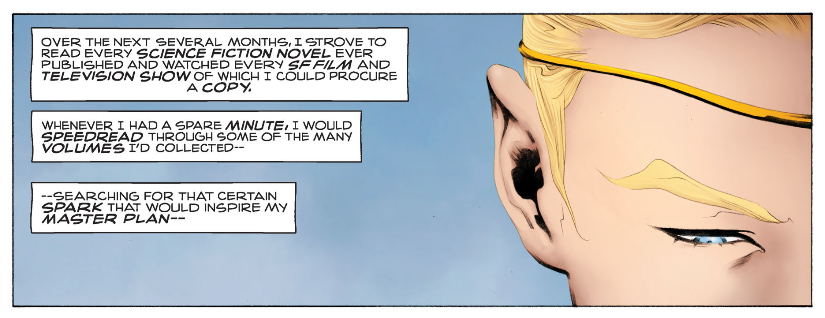

Incidentally, all of these independent occurrences of this same concept serve to make Len Wein’s Ozymandius look like that much more of an inept buffoon:

Every science fiction novel ever published, and you missed all this? That’s some great research there.

While I agree that the ending is one of Watchmen‘s weakest points, it’s not because I think it wasn’t original enough. We are, after all, talking about a story filled with thinly disguised reworkings of old Charlton characters (not to mention that Swamp Thing — the Len Wein-created character that he and Alan Moore first worked together on — is awfully similar to ’40s characters It and The Heap).

The problem with the ending is how naive it is to think that a single large attack could result in lasting world peace. For a real world example, just look at how 9/11 initially united Republicans and Democrats against a common threat, and how quickly they went back to opposing each other once the a sense of constant danger began to fade. It doesn’t matter if that newspaper prints Rorschach’s diary, because without further attacks, everyone is going to go right back to fighting soon enough regardless.

Watchmen may have its fair share of flaws, but at least we can finally put to rest the claim that stealing from The Outer Limits is one of them.

“Sometimes I think the people of this distracted planet will never really get together until they find someone in Mars to get mad against.”

Not “world peace” but “world unification”. Instead of world peace, you have everyone united in a common goal of fighting against a common foe.

The outcome? A militarized space command, with few foes to fight, but engaged in scientific exploration, just in case.

Or, in this case, because of the dimensional ploy, you get “Maple Street”… everyone suspects everyone else of being an alien.

Then there’s the other idea: aliens haven’t contacted us because the business plan is to have the natives extract the raw materials from the planet, cause their own extinction, and then the aliens land and recycle/salvage what remains.

“The problem with the ending is how naive it is to think that a single large attack could result in lasting world peace.”

The ending isn’t naive; Veidt is. Veidt put so much effort into unveiling the “alien” that he didn’t think beyond the next day. And this is pointed out in the book to Vedit after he complete’s his great work. Dr. Manhattan tells Veidt, “‘In the end’? NOTHING ends, Adrian. Nothing EVER ends.” And Veidt is left alone to reflect what he’s become and what he has caused.

There’s a difference between a book and the characters in the book. The book, and it’s creators, know that the plan is flawed; some of the characters do, some don’t.

@Adam: I noticed that line too, but it felt to me almost like might’ve been Moore doubting himself and trying to cover his bases. The reason it felt that way to me is that the final scene showing Rorschach’s journal turning up at a newspaper is meant to play on the tension of, “oh no, if they ever print that, it’ll ruin everything!” The final scene loses its effectiveness if we’re not convinced a lasting change has been made, know what I mean?

*Everyone* has stolen from Jack Kirby.

Everybody “appropriates” from something — Alan Moore did a lot of “appropriating” and Jack Kirby did plenty of “appropriating” – this is of no importance.

The best take the old and make it new again.

@Torsten re: “world peace” vs. “world unification” — that’s an important distinction I should’ve made.

@Charlie & Horatio: At some point I want to do a Jack Kirby version of the parody Bob Dylan Wrote Every Popular Song Ever (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MumScDIZMJc).

I think Alan did care quite a bit about being considered a plagiarist for part of his story. He was diplomatic enough to hold his tongue when his ill-informed editor made that charge and agreed to the outer limits line/nod to complete the project. Most stories borrow/build upon previous stories and Watchmen clearly changes things enough to be non-plagiarism storytelling.

I think it’s obvious that Alan left the ‘ending’ of sorts up in the air for the audience to fantasize about. Does Rorschach’s journal get out and undo the whole thing? Does Veidt’s peace actually hold? The book played with so much left/right/anarchy/order politics that the ending would give readers with whichever viewpoint a way for them to imagine their political view wins, or play out the different ways the story could continue for fun if they so choose. It’s part of what makes Watchmen a great book.

BTW: Great column Kate!

“Everybody “appropriates” from something — Alan Moore did a lot of “appropriating” and Jack Kirby did plenty of “appropriating” – this is of no importance.

The best take the old and make it new again.”

@horatio: Kirby was basically the comics version of the ultimate hip-hop artist. He remixed everything that he saw in pop culture, added an awesome bass line, and put it all together with his accompanists into a mind-blowing new combination that we’d never considered before.

(By comparison, Alan Moore has always just kept taking children’s cartoon characters, filed off the serial numbers where needed, and adding nudity and swear words…)

“I kept telling him, ‘Be more original, Alan, you’ve got the capability, do something different, not something that’s already been done!’ And he didn’t seem to care enough to do that.”

—Len Wein (Wizard, 2004)

>>

He probably didn’t care. For me, the brilliance of Alan Moore was always in his amazing ability to keep a shaggy-dog story going over so many hundreds of pages. When I got to the end of Watchmen (and V For Vendetta, for the matter) I suddenly felt really let down — but then later I would often be thumbing back through these thing(s) and muttering in awe, “WHAT A RIDE !”

Kate, I’d like to see that Kirby version. Actually, did you know the video you linked to was “borrowed” from a Lenny Bruce bit about how Woody Guthrie “inspired” every song that Dylan wrote?

(Not really, but I wouldn’t be surprised.)

Kirby was basically the comics version of the ultimate hip-hop artist. He remixed everything that he saw in pop culture, added an awesome bass line, and put it all together with his accompanists into a mind-blowing new combination that we’d never considered before.

@Brian:

I read where Gary Groth said he found something very “old testament” or “biblical” about Kirby’s stuff .. ever since then, whenever I see Jack’s great work, especially his raw pencils, I think I’m looking at part of The Dead Sea Scrolls (or some ancient tablets that fell from the sky.. or whatever :)

“The problem with the ending is how naive it is to think that a single large attack could result in lasting world peace.”

Even if world peace does not last, the world was on the verge of nuclear destruction. Veidt´s plot at least save the world from that.

And next, with Dr M out of the picture, things should not be as bad, or at least not worse than the real world situation in the 80s.

While the list is long enough already, what the Watchmen ending brought to mind when I first read it was a 1948 Theodore Sturgeon story called “Unite and Conquer.” I always assumed that might have been an inspiration for “Architects of Fear.” Since Jack Kirby liked science fiction, I wouldn’t be surprised if he’d had the Sturgeon story in mind.

In any case, yes, the unite and conquer idea is pretty common, and the question is how it’s used. In both “Architects of Fear” and Watchmen (unlike “Unite and Conquer” or the Kirby story), unite and conquer isn’t the real point, just something that gets you from point A to point B. Someone once complained to Beethoven that the last dozen bars of one of his pieces were taken from another composer. “Any fool can see that,” Beethoven said.

*Edge of Tomorrow* is loosely based on Hiroshi Sakurazaka’s 2004 novel *All You Need is Kill*.

And while the novel may be inspired by *Groundhog Day* in some way (probably the same way as *Hunger Games* is in some way inspired by *Battle Royale*) nothing is really original. There’s always some inspiration.

There is an earlier example of this trope in comic books not mentioned in this article (or anywhere else I have seen): Harvey Kurtzman’s ‘The Last War on Earth’ from Weird Science #5, published in 1951. In the story, a scientist secretly initiates an attack on Earth (in this instance an atomic missile attack) which he intends to convince the populace comes from Mars, in an effort to unite Earth and ‘end war’.

He tells his confidant: “I’ve set the controls so that Middleburg… will be blown from the map. No more than 300 people will be killed! But what is 300 compared to the millions who will be saved when wars cease?” Prior to that he tells him: “The threat will come from up there! From that red planet named after the god of war… I’m going to make the people of the world think they are being attacked by the planet Mars!”

At the conclusion of the story, In the EC ‘snap ending’ style, there is a surprising, ironic twist.

Pure speculation, but it wouldn’t surprise me at all if it was a young Alan Moore’s (a child of the 1950s) first exposure to this concept. Knowing his work as I do I think it is the single most likely source as anyone familiar with both classic EC comics and the full body of Moore’s work will be able to notice a large formative influence on the young Alan Moore.

I feel that Moore’s Kurtzman / Feldstein / EC comics influence is largely unexplored but is quite significant.

Too many people generally are unread in EC comics. Anyone who fancies themselves as ‘knowing’ western comic books should prioritize reading the entirety of their New Trend output.

The thing is, Alan Moore does borrow idea from others. The big reveal at the end of From Hell is lifted (without alteration) from the 1970s Sherlock Holmes movie Murder By Decree, which is also about Jack The Ripper. I don’t think that Moore has ever commented on this as the parallel is not just similar, like in Watchmen, but identical.

Comments are closed.