This week: Alex presents a mildly spoiler-y advance review of Superman: Year One.

DC Comics is trying something new. In the wake of their Rebirth initiative, the publisher has rapidly expanded its content to include diverse new imprints such as Young Animal (redux!), Wildstorm, Jinxworld, Wonder Comics, Black Label, Ink, and Zoom. As their lineup expands, it can be hard to figure out what to pick up each week. That’s what our team is here to help with, every Wednesday, with the DC Round-Up!

Note: the reviews below contain spoilers. If you want a quick, spoiler-free buy/pass recommendation on the comics in question, check out the bottom of the article for our final verdict.

Superman: Year One #1 & #2

Superman: Year One #1 & #2

Writer: Frank Miller

Artist: John Romita Jr.

Inker: Danny Miki

Colorist: Alex Sinclair

In many ways, Frank Miller has had one of the most curious careers in comics. There’s no denying that his work has been massively successful and influential. At his creative peak as a writer and cartoonist, with works like Sin City and The Dark Knight Returns, one could argue the he reinvented the characters he worked on and expanded the possibilities for comics more broadly. Even some of his more maligned work, like The Dark Knight Strikes Again, has a certain creative fervor that’s hard to ignore. But then there’s work like Holy Terror, an Islamophobic screed that Miller has only recently somewhat disavowed in a public way. There’s also his depiction of women more broadly, which often reads as degrading, fetishizing, or both. This complicated legacy is what Miller brings to his latest work, Superman: Year One.

On its face, Superman: Year One is a sibling to Batman: Year One, Miller’s, David Mazzucchelli’s, Richmond Lewis’, and Todd Klein’s revered take on the Dark Knight’s origin story. But where Batman: Year One focused specifically on a turning point in the lives of young Bruce Wayne and Jim Gordon, to call this new Superman book “Year One” is more of a spiritual evocation than a temporally accurate description of what Miller, Romita, Miki, and Sinclair try to do within these pages. Superman: Year One is less about a formative year than it is about a formative life, where chapter focuses on a different point in Clark’s long journey to becoming the Man of Steel.

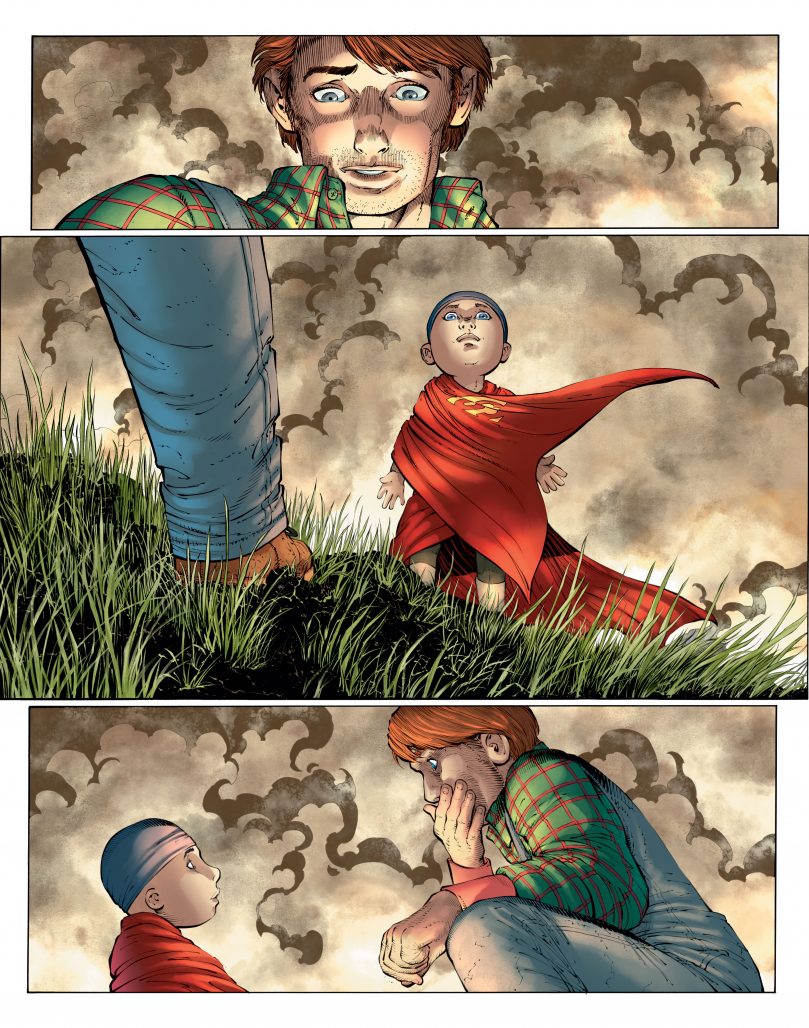

Superman: Year One #1 examines Clark’s childhood, from his birth and the death of Krypton up until the point he becomes a legal adult. It’s clear in a variety of ways that this version of Kal-El is written to be a messiah figure. As the baby who will become Superman crashes down to Earth– a scene we’ve seen time and time again now– the omniscient narrator tells Clark that “a world needs you. A world you must save.” And as Clark meets Jonathan Kent for the first time and examines his farmland surroundings, he wears a fascinated expression as the narrator says “Everything on God’s Earth– it’s like it was all made just for him.” If you really need the comparison hammered home, the first thing we see Martha Kent do is address a farm worker named Hiram. The reason why I point this reference point out is not to say it’s novel– we just saw Zack Snyder play out this version of Superman on screen– but rather because it is a big clue to what kind of world we’re going to be presented with throughout this book.

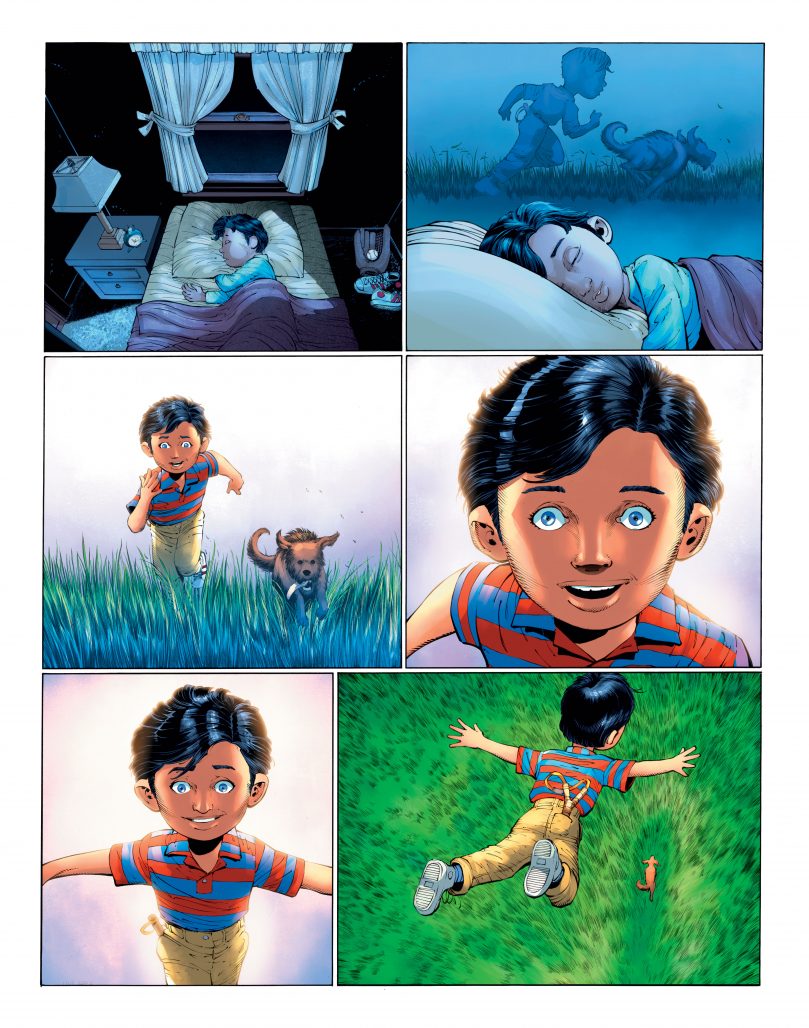

The reason why Zack Snyder’s version of Superman as messiah did not work for me was because that version of Clark felt more like a miracle machine than a man. As much as Man of Steel talks about Clark needing to balance his superhuman nature against his humanity, it– and each subsequent DCEU movie that features him– rarely shows us Superman’s human side. That’s not the case in Superman: Year One, and it is absolutely where this book shines brightest. Much of the first issue is atmospheric. It’s driven by a sense of discovery rather than conflict. There’s a beautiful sequence where Clark, lying in bed, discovers his super-hearing because all the nocturnal animals around him keep chattering. And there’s another beautiful bit where Ma and Pa Kent lose a young, fast-running Clark in their farm’s tall grass. They wonder where he’s gone, and then see him leap over their heads for the first time– a first step on Clark’s journey towards flight. They marvel. I marvel.

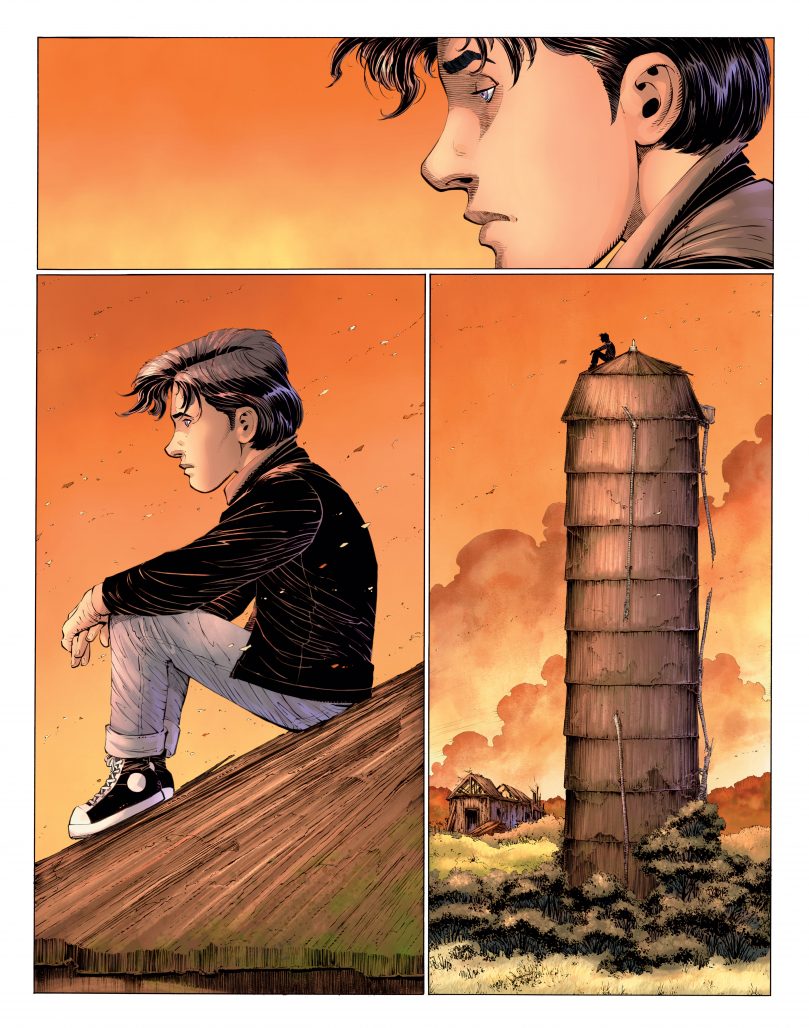

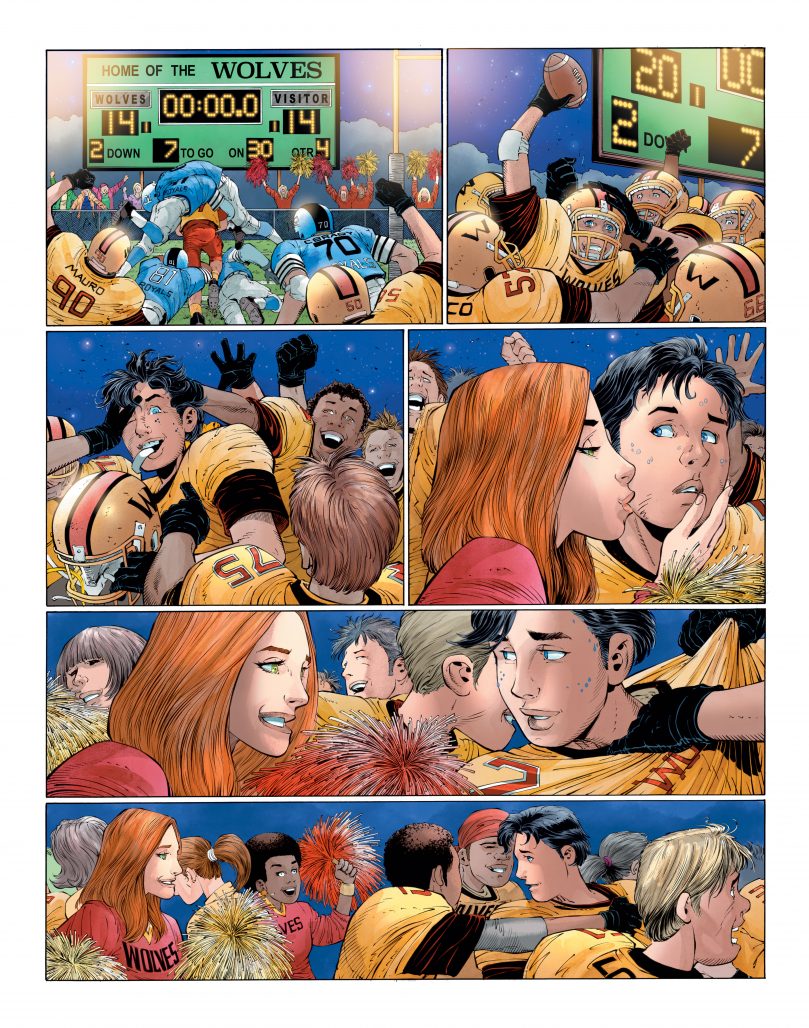

Even after the first chapter turns towards a more central conflict– how Clark, now a teenager– should moderate the usage of his gifts at school, the thematic exploration is mostly done well. When Clark’s “weirdo” friends are bullied, he is pulled into a moral dilemma about what it means to exercise restraint in the face of injustice and what it means to fight back when you’re so much more than your opponent– than anyone else on Earth.

This book’s version of school life feels rooted in an older version of Americana– there’s a scene in a classroom where the kids don astronaut helmets that feels more of the 1960s than the 2000s. There’s also not a smartphone to be seen, although we know they must exist, as the narration mentions them at one point. Really, the whole book feels temporally displaced, which works in some ways but feels strange in others. The kids at Clark’s school are relatively racially diverse, but there’s no exploration at all of any topical issues facing America today– whether it’s race relations, gender expression, or sexual orientation.

This isn’t to say that every story should aspire to cover every subject. But the notable absence of topical subjects and objects in this story– there are literally no screens more advanced than a football score counter in this book– reads like an active omission of anything that might inspire controversy. Instead, we get this small-c conservative version of the world in Superman: Year One— a world that seems to belie some amount of desire for the “good old days” of America. It’s a world where we don’t talk about race. It’s a world where Clark forgoes college in favor of enlisting in the navy at the end of the first issue because it’s obviously the way a man can see the world and find purpose in life. And it’s a world where gender roles are ultimately built through the lens of men.

Indeed, it’s in Superman: Year One‘s treatment of women that we see the most regressive storytelling in this book. Martha Kent is as “traditional” a mother as they come, telling Clark that violence is never okay so Jonathan can later come into Clark’s room, alone, and get the hero moment where he recontextualizes when it is okay to use violence. Lana Lang, presented here as Clark’s high school sweetheart, has a little more spark and agency, but it’s ultimately robbed from her when Clark has to…save her from being raped. After that, she mostly is just Clark’s love interest, marveling at his strength and ability to speed-read. Their relationship is visually presented as relatively earnest in spite of the horrible sequence that precedes it, but we never get to see Lana process her trauma or even, really, see why Clark idolizes her in the way that she idolizes him.

Moreover, the way Superman: Year One #1 ends, with Lana giving Clark a tearful goodbye as he leaves for military training and they promise to not forget each other, is sweet, but it’s completely undercut by the fact that Lana doesn’t even get a mention in the second chapter. Instead, Clark meets a mermaid named Lori. The two of them idolize one another for reasons that are also unclear besides the fact that Lori is beautiful, singing an alluring siren’s song; and Clark is superhumanly strong (notably, Lana is also compared to a “siren” in the first chapter). However, standing between their love is Lori’s father, Poseidon, who treats Lori as a possession and whom Clark must fight for her hand. This is a tired and staid presentation of relationships and gender at this point. The women in this book simply deserve better.

So after all this– what to make of Superman: Year One? It’s a visually beautiful book, with Sinclair finding the perfect balanced palate that adds depth and emotion to Romita Jr.’s art without overshadowing it. And to be honest, I think the book presents a specific sort of world view rather compellingly. It’s not a world view I agree with in any way, but these first two chapters of Superman: Year One explore what it means to grow up with a certain perception of manhood and destiny. And as much as it seems to revel in the positive aspects of that sort of world view, it also interrogates that perspective at times– even if they’re primarily at times where to not do so would fundamentally alter Superman’s character as we generally understand it. Yet somehow, even in light of that questioning, there still manages to be an enormous blind spot in this book when it comes to women. And more than that, it feels like this book actively avoids exploring topical hot button issues and interrogating how its general worldview connects to current the political situation in America.

As much as Superman: Year One tries to exist in a temporally isolated bubble, choosing to warp the world of your story in order to avoid touchy subjects is, in itself, taking a position of sorts. In its attempt to come off as timeless, Superman: Year One somehow feels dated. Like it came from the mind of someone or someones who long for times that felt simpler if you looked at them through the right lens, even if they weren’t, in actuality, any better for everyone.

Miss any of our earlier reviews? Check out our full archive!

Jesus god, but Romita is a terrible artist. Those shots of toddler Clark running make him look like a anthropomorphic lollipop.

JRJR is the reason I leave books. Just an opinion.

You and I watched very different Zack Snyder DCEU movies because I thought they bled humanity.

Also disagree with the ways you characterise Miller’s writing of women, and of ways to understand Holy Terror. Y’know, in a sophisticated way, situated, discursive and bifurcating of things that don’t disappear, and even if they’re ugly. Am I happy on both these counts? Yep. (and I’m not a raving Right-wing, sexist nutbag. Funny, that

Comments are closed.