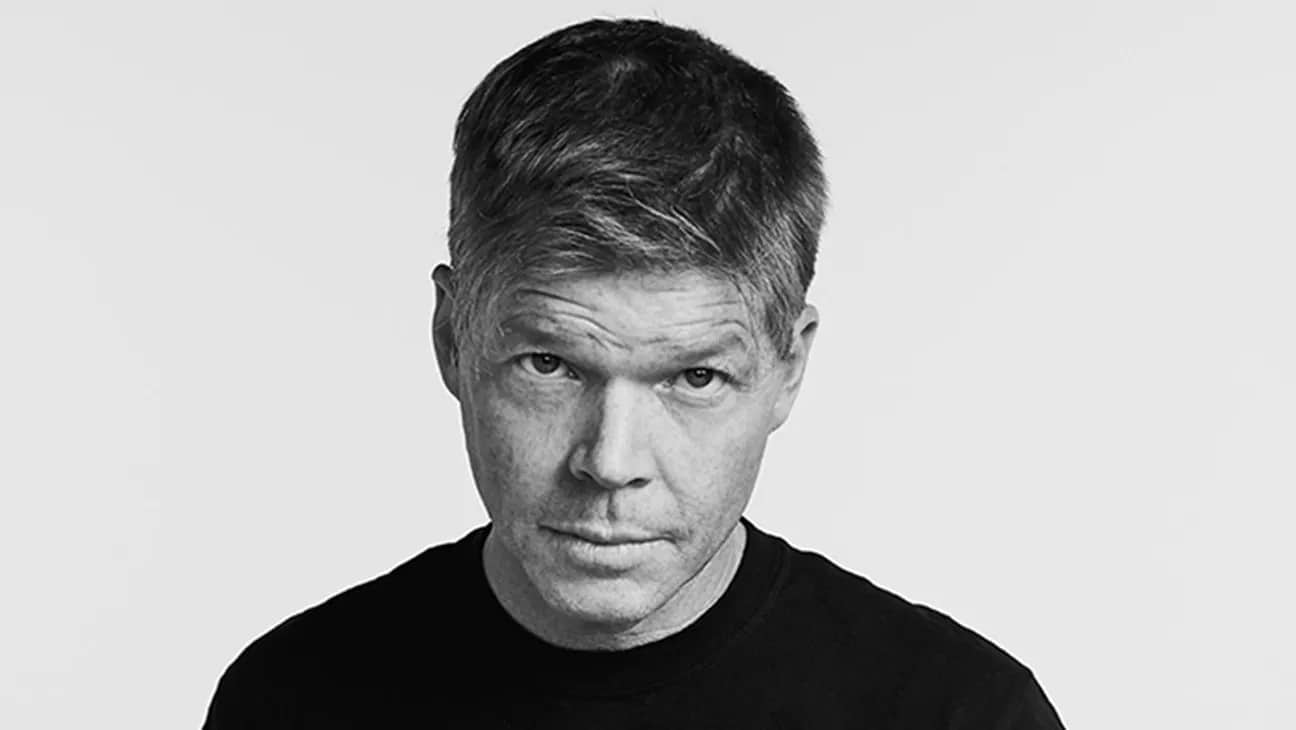

David Brothers is one of the most accomplished writers-about-comics around, a blogger who recently moved into the industry himself as a member of the Image Comics staff. Having made a name for himself on websites like 4thLetter and Comics Alliance, his writing on (in particular) creator-owned comics, artwork, Manga and race have provided some of the more compelling and articulate dissections of the industry of the last few years.

He’s one of the best, basically, and a number of other bloggers – myself included – see him as the pacemaker for our own writing. After a brief – very brief! – meeting in New York, David kindly agreed to talk to The Beat about his new role at Image; his thoughts on comics, genre, diversity and ownership; as well as where he hopes the industry will progress to over the next few years.

His answers are extensive – and well worth reading.

Steve: What persuaded you to make the move into the comics industry, after years of blogging, critiquing, and editorials?

David: The short version is that I had a meeting with my former bosses, and midway through the meeting, I realized that I had to quit my job, that staying where I was would be a tremendous mistake. I had no opportunities for growth, economically or in terms of promotions, and I was pretty unhappy with where things were going. The problem was that I dropped out of college for the job, and had spent most of my twenties specializing in one specific industry, and I had no idea what would happen after I quit. Compounding things was the fact that ComicsAlliance, my regular freelance writing outlet, had been shut down a couple weeks earlier, so I was feeling more than a little like I was SOL.

But, while walking to the bus home that day, Ron Richards, who is a friend and someone I worked with and/or for at iFanboy for a brief bit, sent me a message asking how happy I was at my job. Very soon after that, I had an interview with Ron & Eric Stephenson, and the Monday after that interview I put in my two weeks notice at my video game gig.

It was a blessing the way things worked out, because I was looking at worst-case scenarios, and how it happened was a total surprise. So it wasn’t a conscious move on my part, but… A musician I like a lot by the name of Vast Aire once said, “Opportunity was like, ‘Fuck knocking, I’ll pick the lock.’”

It was a lot like that.

Steve: What is it about the concept of editing, building up comics which most interests you? Was this something you’d always wanted to get involved with?

David: Editing was on my radar as a thing I could do, and I’ve done it freelance here and there (and for free when people asked nicely, in hindsight), but I never thought about editing comics as a career. I went through a very brief phase of wanting to write comics for myself before deciding writing comics wasn’t for me, and that’s about as close as I came to wanting to be “in the industry” in any real sense of the phrase.

I do enjoy it, though, because it works muscles that I enjoy using. Looking at a story, spotting what’s great and what’s not, figuring out how it fits into several different greater contexts, and then figuring out how to explain that to a creative team without babbling—helping people do the story they want to do, basically—all of that appeals to me. I like support roles and helping people out a whole lot, whether it’s being there as a sounding board for ideas, giving input on art choices, or even going “What if this? Where would that take it?”

I like getting a chance to see a story gestate before it’s released, and hopefully making it better than it would have been without me. I don’t ever want to make it worse, or to sandbag a book or not pull my weight. If someone trusts me enough to be their editor, then I need to be able to come with my A-game every single time. But the most interesting part to me, I think, is what is required of me to even attempt to rise to that challenge. With comics blogging, I’m beholden to myself, and only myself. Working with others, collaborating on something, requires more effort —a different kind of effort—than my usual mode. It’s like solving a new, but familiar, puzzle. It’s a different feeling than examining a finished work.

A shorter version of this answer is probably “I like the challenge.”

(I like the finished work a whole lot, too.)

Steve: How do you feel that moving ‘behind the scenes’ has changed the way you connect with comics, yourself? Do you feel more aware of production now?

David: I’m trying to think of something I’ve learned since starting at Image that would make me recant some of the outrageous nonsense I’ve talked over the years, but honestly, my connection to comics has always been a work in progress. Being able to tell if lettering is rich black or 100K hasn’t really changed how I read comics, you know? It’s just another tool in the box.

I definitely connect with comics differently than I did this time last year, though that isn’t necessarily a result of joining Image. I quit Marvel and DC in 2012, which caused a seismic shift in my comics reading (and writing) habits, and joining Image shifted them again. Having comics for a job has made me even pickier in my personal comics reading, just like working in video games made me very picky about playing games at home. The stuff I’m into hasn’t changed much, beyond broadening a bit as people introduce me to new things, but how and when I read has.

When it’s not winter, I mostly read comics on the weekend. I have a little lawn chair, a short table, and a tiny balcony at my place. I’ll wake up on a Saturday or Sunday, work out, and then chill outside for a couple hours going through books, reading on my laptop or iPad, and listening to music. If I’m riding the bus or a train to work, I’ll bring a book along there. I’ll read some manga before bed here and there, but I rarely read for long periods of time during the week, outside of special occasions, books I’m really into, or Weekly Shonen Jump, which I read as soon as I can.

I work closely with production and marketing over the course of my job, but I don’t know that it’s changed my connection with comics. I definitely wrinkle my eyebrows when I see wordless pages now (“Wait…was this intentional? Or did a layer end up turned off?”) and I totally get how certain baffling-but-common errors happen now. But as far as changing my relationship with comics—nah, not really. That relationship is always evolving and probably always will evolve.

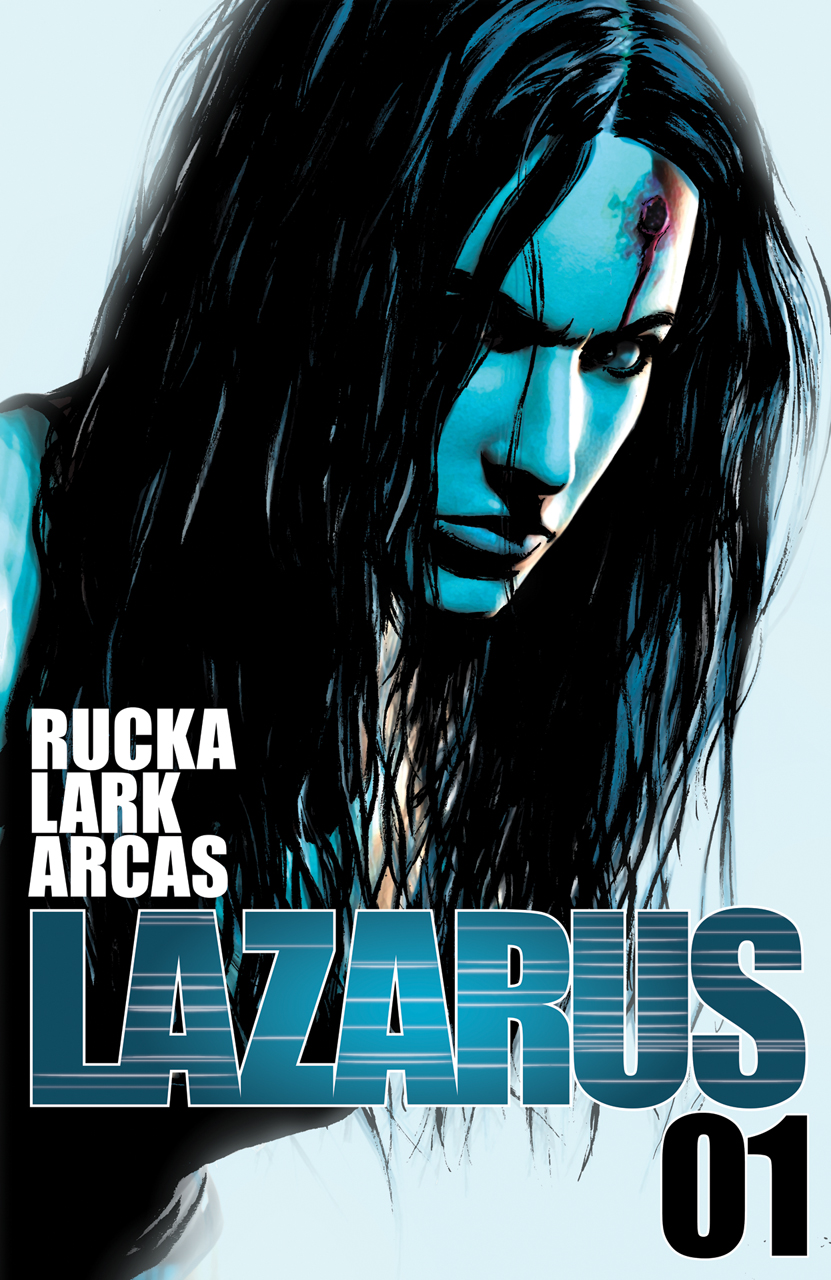

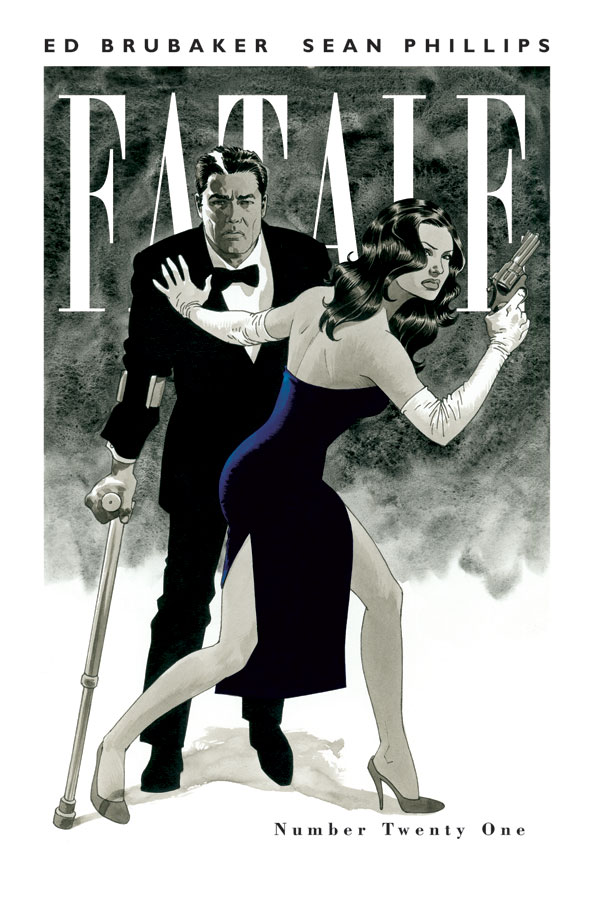

Steve: From what I’m aware, the comics you’ve been involved with at Image are books like Fatale and Lazarus. Do you have a particular interest in crime or noir stories?

David: I do! My first “adult” comic, or “comic with cuss words and nudity” more accurately, was Frank Miller’s The Big Fat Kill #5. It made a huge impression on me, which was only compounded by the books my mom was reading around the same time—James Patterson, Patricia Cornwell, folks like that. I kept seeking out these stories as I grew up, from Scarface to Payback to Stray Bullets. My favorite movie to this day is Out of the Past, with Jane Greer and Robert Mitchum. My favorite genre of music is rap, and rap is positively lousy with great crime tales. Ghostface Killah & Jadakiss’s “Run,” some of Nas’s Illmatic, Bone thugs-n-harmony’s Creepin’ on ah Come Up, Killer Mike’s “Dueces Wild,” TI’s Trap Muzik…

I grew up absorbing more crime than any other genre, and across a variety of modes. I probably define it a little wider than most, too, but it works for me and I can back it up.

Steve: What is it about the concept of a crime story which has such lasting depth to it? Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips have been building crime stories for years, but there’s been no repetition in their work.

David: I think the barrier for entry to a crime story is much lower. All you have to believe to buy into your average crime story is that one man with a gun can ruin someone else’s day, or that a stray bullet can have effects that echo down through the years. Even when it’s pure fantasy—leaping out of windows, firing two guns simultaneously, invincible protagonists, cliché plot twists, inexplicable headshots—it’s still something you can look at and go, “This is familiar. This is real,” because the foundation is familiar. I have a hard time with a lot of sci-fi, and especially faux-medieval fantasy. Even something as rooted in political maneuvering and realpolitik as Game of Thrones makes me want to fall asleep in protest or re-read a Parker novel or something.

Crime stories—and maybe this is true of all stories but specifically crime stories here—are about bad decisions and consequences. Tony Montana makes a series of bad decisions that wreck, and eventually take, his life. The goons Richard Stark’s Parker goes up against chose to break their word and suffer the consequences accordingly. Kendrick Lamar, on good kid, mAAd city, has to live with the choices other people made and his own bad choices.

We all make bad decisions, and a lot of us spend a lot of time trying to recover from those bad decisions. I look back at my teenaged self and I wanna fight me for the decisions I was making at the time. We all know what it feels like for a good idea to go horribly wrong. We definitely know what it’s like to hope nothing goes wrong after you screw up, I think.

So it’s very easy to relate to, even if you don’t own a gun and have never thrown a punch. My favorite crime stories have some type of basic thematic hook you can grab onto, whether it’s Parker’s professionalism and anger (have you ever thought “Why didn’t you just keep your word, idiot?”), the Leverage crew’s guilt and hope for a better world, or even the idea that one person in the right place at the right time with ten thousand bullets can make a lasting difference. (They generally can’t, but that’s why crime fiction is just another wish-fulfillment fantasy.)

I think Ed and Sean do particularly well at the poor decision-making spiraling out into something horrible. I dig all of them, but my favorite Criminal arc is Last of the Innocent, and it’s fundamentally about veiled Archie characters making increasingly awful decisions and trying to get out of the consequences. You read it, your eyes bug out, and even though they’re terrible people, part of you wants them to get away scot-free. Another part of you wants them to face bloody justice.

Crime stories let us see horrible things play out in someone else’s life in a very grounded (my preference, at least) way. It’s like watching a trainwreck, and the only people that get hurt are fictional and probably have it coming anyway. And my preferred style of crime, the Stark/Elmore Leonard/James Ellroy/Walter Mosley works, is clever, too, with amazing prose and exceedingly cold-blooded acts dressed up in incredible language. My most favorite bit of prose ever is in Stark’s The Outfit, where a group of thieves break into an office dressed as mailmen and Stark details the receptionist’s utter inability to recognize the reality of what was happening. It’s a short scene, but it’s beautifully written.

Steve: Both the comics I mentioned have fantastical elements, but the crime genre does add an idea of realism to the stories. Do you think there is a growing interest or need in companies publishing comics in more ‘realist’ genres – like crime, or romance, or similar?

David: I’m not sure that it’s realism exactly, but I think the general interest is definitely there. But that’s more a result of the comics industry finally catching up to the rest of the world. Comics can support a wider variety of genres now, and you can buy them at more than just comics stores. I think that’s the thing that has led to more work in other genres getting a chance to shine. I don’t just want to read one type of comic, and I figure a lot of people are the same as me. Someone out there wants this stuff, I think, and it’s nice that we can finally get it.

Steve: Do you think that the range in diversity of genres and styles of comics – Manga’s influence; the arrival of Korean Webtoons; European and South American comics in American stores – has diversified not just the readership of comics, but also the people who are inspired to make comics themselves?

David: It absolutely, objectively has. To dial it back a few years—Frank Miller is one of the most important artists in comics, and had a killer 1985-1986 in particular. He was unquestionably putting up Michael Jordan numbers. But Frank Miller wouldn’t be Frank Miller if he didn’t discover manga. This was long before manga was as mainstream as it is now, before kids across the country grew up on it as being a normal part of their reading experience.

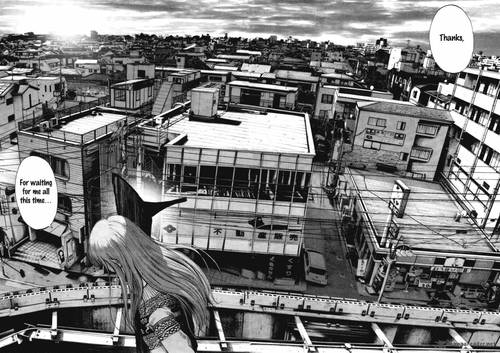

Art by Inio Asano

So if we look at today, where manga has been more-or-less mainstream for a good long while, the possibilities are endless. There are a few groups of creators making neo-shoujo comics, I personally know two different people working on tokusatsu/Super Sentai-style comics, there was an issue of Batman recently that honored the work of Shotaro Ishinomori to an extent…this is new. It’s an ongoing conversation between the creators and their influences, as they process and incorporate what they’ve learned or absorbed from these books.

I’m looking forward to seeing what autobio comics influenced by Inio Asano or Taiyo Matsumoto instead of Chris Ware or whoever will look like, what kind of action scenes people raised on Akira Toriyama or Hiromu Arakawa will do, the types of stories that a fiend for Kazue Kato will create. I’ve spent hours in hotel bars at cons talking about exciting comics with people around my age, with nary a mention of anything American.

Influence isn’t everything when trying to predict what will come forth, but it does matter a lot. It’s sort of like a blind drawing, in the lottery sense. If you only have aspects of American comics in a hat, then you’ll have a lot of variety, sure, but a limited toolkit. If you throw in manga and everything else, you’ll get more variety and more options.

So, for instance, people who like vampires but not superheroes could have gotten heavy into Vampire Hunter D, Blood+, Hellsing, and Vampire Knight as teens. That shows them not just that comics exist that they’re interested in, but if they’re willing to tell stories about that stuff, then they can make comics and find an audience, too. We’re seeing it now, I think, and it’s only going to get better as time goes on and people age into the industry.

I love it, because while capes were my first love, I’m super into all this other stuff, too. The stuff I’m seeing now feels increasingly like “my” comics, where I get a lot of the foundation of books because I have the same frame of reference the creators do.

The mainstream view of comics is generally superheroes, since that was the dominant genre for so long. If you never scratch the surface, then you’ll think comics are superheroes. But if you grew up with a parallel tradition, for lack of a better phrase, you know and can do more, and that’s true whether we’re talking diversity of storytelling or diversity of the talent on your books. More voices from more places means more variety means more opportunities.

Steve: As a black reader, would you say that you feel more represented within contemporary comics now than ever before? Or do you feel there is still a noticeable lack of representation for, in example, African-American readers?

David: Definitely, though not if I limit it to just superheroes. Capes are better than they were for the most part, but the cape comic that hits as hard as Ronald Wimberly’s Prince of Cats, where I recognized half the cast as people I personally knew growing up, or Marguerite Abouet and Clément Oubrerie’s Aya, which serves to show how normal growing up black is.

On a mainstream level, speaking specifically of the “Big Seven” side of the comics industry, representation sucks, but is getting better. But mainstream works service a small market and are subject to the whims of that market, and that market, at least so far, isn’t really into representation, judging by sales and such.

But if you break it out to comics as a whole, the ration feels way better. I know of at least two different ongoing black-centric comic conventions—ECBACC and OnyxCon—and that’s utterly wild to me. OnyxCon is in my home state, even. We’re in comics, we’re making comics, and we always have been. It’s just becoming increasingly obvious now that things are more democratized. The demand is there, and the supply is getting there.

I think there’s still a noticeable lack, but I feel way better about it now than I ever have in my entire life. We’re getting there. I’m hopeful. But until I feel content, I’ve got to keep banging the drum for more creators, better works, more nuance, and a definition of comics that includes all these wonderful books, too.

By Ronald Wimberly

Steve: You’ve recently been producing a series of spotlight pieces for Robin McConnell’s Inkstuds podcast. Where did the idea for this come about? Do you have any particular hopes or goals for the interviews, going into them – or is the plan to just see what happens once the recording starts?

David: It started like most of my ideas: Half the things I’ve ever written were me trying to organize my thoughts, or to figure out something I couldn’t crack without putting pen to paper. In January, the thought of trying to build a picture of what people in and around the comics industry actually do crossed my mind. I’ve been trying to figure out a way to have a conversation with various industry types for a while, and Robin McConnell has been wanting me to contribute to Inkstuds for at least a year now. His 500th episode gave me a good entry point after months of stalling on my part.

I pretty much had the idea one morning, emailed Robin and Joe Hughes at ComicsAlliance a few minutes later, worked out my list of people over lunch, and started reaching out to people by the time I got off work. Before the first episode goes up, I’ll have all but one or two of the interviews done. I don’t want to blow the line-up, but everyone I asked leapt at the chance, which was tremendously flattering. They were so enthusiastic and energetic and into the idea that it was humbling. I’m intensely grateful to them for being down, and not just that, but being fascinating. I’ve learned a lot, and I spent a bunch of hours one weekend on this and came away from it feeling like I could shoot lightning bolts from my fingers. I’m hyped for my own project, to a level that is rare for me.

As far as my interview approach…for this project specifically, I have a list of notes or prompts that I read over before the encounter, including stuff like things they’ve worked on to specific questions. I’m a dedicated note taker, though they’re more personal and mnemonic than informative to anyone but me usually. The act of writing the notes is usually enough for me to have them in my head, and I’ll sketch out notes while people speak if they say something I need to remember or follow-up on. But once Skype is up and running and they say “let’s go,” I freestyle it. I trust myself to know my subject, their work, and to be able to handle any curveballs. I want them to lead the conversation more than I want a specific list of questions answered, if that makes sense. We can and often do get to the questions, but on their terms, not mine. I’m here to listen.

My favorite interviews to do are more like conversations than anything else, or maybe lessons, instead of a pure Q&A. I like setting people up and letting them run with whatever’s on their mind, and I especially like digging into what they say. This is another thing I learned to do by watching others. You can tell which interviews have follow-up questions and which don’t. The ones that do tend to be good, because the interviewer is engaged and interested enough to want to follow-up or challenge the interviewed. That’s what I’m aiming for with Inkstuds Spotlight, something closer to a conversation than a pure interview. That’s my goal, at any rate.

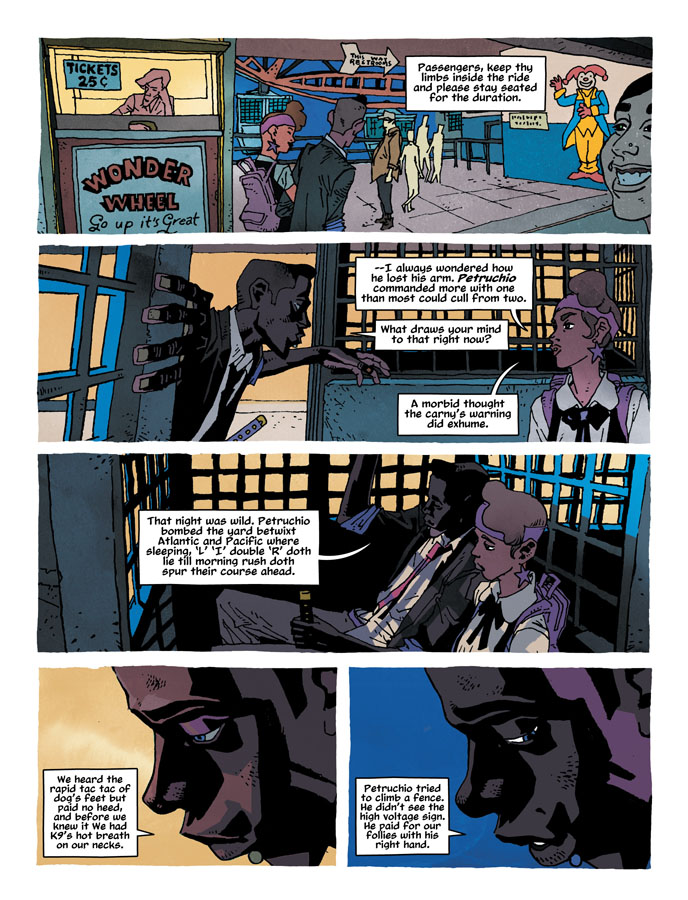

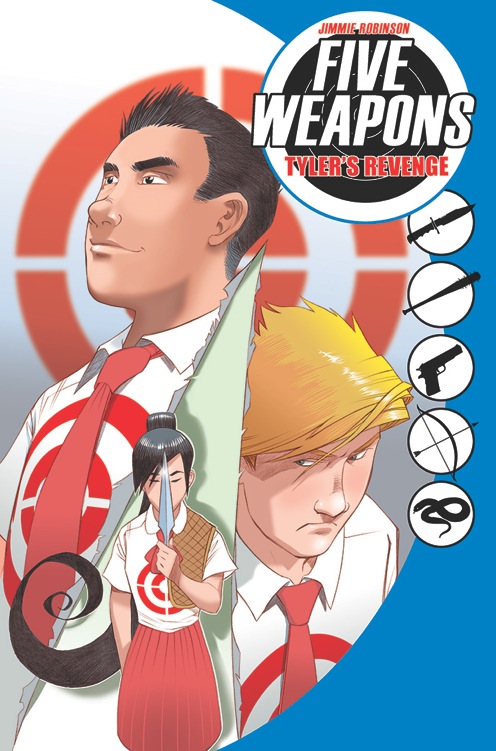

Five Weapons by Jimmie Robinson, one of the interviewees on Inkstuds Spotlight

It’s not going to be a comprehensive look, or holistic. I’m trying to tap a few people whose work I’ve found interesting and get them to tell me why they got into comics, what they get out of it, and then some facts from their life and work. I think I’ve only interviewed one of the line-up before, and while I’m familiar with all of them, this is really just me getting a chance to pick their brain to satisfy my own curiosity and letting other people eavesdrop.

Steve: Do you think we’re now heading into an era where creator owned comics have as much visibility as work-for-hire franchises?

David: Not yet, but we’re inching our way there. Marvel and DC are going to dominate the conversation as long as they’re making billion dollar movies, and that’s a tough mountain to climb for any creator-owned work. I’d love it if there was parity, but figuring out that solution might be a bit beyond my pay grade. The Direct Market is biased in favor of the Big Two, because the DM spent a lot of time building an audience who wanted Big Two comics, so non-Big Two stuff in general is going to be secondary for a long time, no matter how good or original it is. But the more people pay attention, the better things will get, right? Hopefully. I think we’re moving in that direction, and hopefully we can sustain that momentum.

But then, outside of the DM, Raina Telgemeier runs the New York Times bestseller list. Japanese and European comics are wildly diverse. Maybe the world is already ten steps ahead of us, and the DM is just trying to catch up.

Steve: What do you think has been the appeal of Image, as a brand, as a company, over the years? It’s certainly great that the books are creator-owned, but do you think readers in stores respond – or even understand – that concept as something worth supporting?

David: My first comic ever was Todd McFarlane & David Michelinie’s Amazing Spider-Man #316, and one of the first comics I bought with my own money was Jim Lee & Chris Claremont’s X-Men #1. Portacio was on Uncanny X-Men, Liefeld was on X-Force. As a kid, the appeal of Image was the art, though I wasn’t thinking in those terms at the time. They just had the best-looking books ever. They caught cool in a bottle, and I had a front-row seat as a kid.

Nowadays, now that I’m grown, the appeal is largely due to the variety. On my desk right now are Stuart Moore & Gus Storms’ EGOs, Kel Symons & Mathew Reynolds The Mercenary Sea, JMS & CP Smith’s Ten Grand, Chris Dingess & Matthew Roberts’s Manifest Destiny, Robert Kirkman & Charlie Adlard’s The Walking Dead, and Brubaker & Phillips’s Fatale. None of these books feel like each other in any real way, and I think that’s a great thing. There’s a certain level of diversity in cape comics, but they’re still all under that cape umbrella. I love Frank Miller’s Daredevil, I love Romita/Conway and McFarlane/Michelinie Spidey, but they’re superhero comics first, and crime and romance comics second. As much as I like Cape Comics Plus, it’s cool to have books that are just full-on “This is a maritime adventure story” or “This is about people getting beaten up” stories.

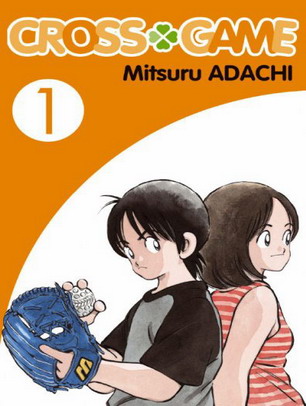

I think people respond to variety, and like your question earlier about genres elbowing their way into comics, it increases the odds that someone out there is going to go “Oh, I like baseball and there’s a really good comic about it now? Awesome.” (Mitsuru Adachi’s Cross Game, available now) Anybody who tells you otherwise ain’t really in the money-making business.

Art by Mitsuru Adachi

I love creator-owned comics, but I don’t know that it’s a selling point or value-add for most people. That’s a business issue, and it’s not as sexy as organic food, so basing a campaign around that, instead of the work, always feels like inside baseball.

Steve: Do you feel there is an immediate way that we could move the industry along in terms of diversity, or is this going to be a long-term action that takes years and years to progress?

David: It’s going to be years, because the comics industry is a part of American culture, and American culture is still recovering from being rooted in white supremacy, among other things. There’s no off switch for hundreds of years of conditioning, trauma, and unfairness. That’s a ton of inertia to combat. You have to chip away at it, taking big chunks when you can (the Civil Rights movement, for instance) and settling for small slivers when you can’t (telling a friend why it ain’t cool to say “retarded” any more).

But while that process works itself out, everyone involved has to be more proactive. Nothing ever fixed itself, even when it was mind-bendingly obvious and just. The process needs elbow grease and agitation. You’ve gotta be willing to try something outside of your comfort zone as a reader, publishers need to look beyond their rolodex and actively scout a broader range of talent, retailers need to be able to push a wide variety of content, and the press has to pay attention, too.

It’ll take years, and it’s getting better, but there’s no reason it should take forever.

Steve: You recently put up a question on Twitter asking what comic book websites would be doing to champion black creators during Black History Month. Do you think the comics media plays an important role in showcasing and spotlighting creators?

David: Yeah, to a certain extent. I don’t think that the media can make or break someone’s career, but they can definitely get someone’s work in front of someone who actually can. The way the press talks about comics affects the way we all talk about comics. It can start conversations or shine a spotlight where it’s needed. The press has got to start reflecting the vast spectrum that makes up “comics.” The “comics industry” sites, even the ones focused on criticism, rarely talk about webcomics, for instance, or the thriving scenes outside of the currently accepted dimensions of the “indie comics” umbrella. What manga coverage there is on big comics sites tends to be good thanks to great writers like Brigid Alverson and Deb Aoki, but it feels so few and far between sometimes. Akira Toriyama is one of the most important cartoonists ever, and “He’s from Japan tho” isn’t a good enough reason for the almost hilarious lack of coverage, with just a couple exceptions, of his latest work.

Comics is comics, whether it’s European, Japanese, Filipino, Chinese, or American. The arbitrary lines we’ve drawn as press are baffling to me sometimes. I feel like the comics press doesn’t accurately reflect “comics” right now, and that’s frustrating as a reader and critic. There’s a lot of great work out there that could use the discoverability that comes with informed and engaged press coverage, and when you cast your focus so narrowly, you miss out on a lot. You can’t cover everything, obviously, but covering the same stuff over and over is boring.

Steve: What do you think websites – like The Beat – should be doing to encourage diversity?

David: Widening the focus is something that would help. But speaking specifically on black-oriented racial diversity, generally about comics sites (meaning “not just The Beat”), and as someone who has been having the same conversations on the same subjects pretty much ever since he started writing about race and comics: comics sites need to stop with the dilettante approach to race and comics, and the people writing about it need to step their game way up. I include myself in that critique, of course, because I’ve definitely fallen short in that arena.

As a kid, my friend group read comics, but we got comics from white men, and they were made mainly by white men for an audience of other white men. Marvel’s Bullpen Bulletins profiled a couple of black creators and editors, but I had no real idea that black people could make comics until I tripped over Milestone. Black characters in comics often felt like a weird pantomime of actual black life, an impression of an impression, and that’s an implicit sign in a lot of ways.

I feel very strongly about not just encouraging diversity in comics, but making it plain that the diversity that is already there is worth paying attention to. I started doing yearly Black History Month sprees on 4thletter! because I felt there was a severe lack of coverage of that realm. It took me forever to figure out my approach, and the best way to get my points across on top of that, and I’m still refining because I’m still not happy with my work, and most of the coverage I see is annoying.

I take race and comics coverage seriously, or maybe personally, because it’s a subject I can’t help but have a vested interest in. While it’s a genuine cause for others, or a way to show how liberal they are at the expense of someone else’s mistake, this is actual factual real life for me. I grew up feeling like I was boxed in, and I rarely felt like there was an escape hatch. I have a very young little brother and even younger little sister who don’t deserve that. I write because I care a whole lot, and when I see people using people like me as chess pieces in a battle I’m not invited to, I definitely feel some type of way. When I see groups of well-intentioned white people belittling or ignoring the input of non-whites in arguments, I get frustrated. When I see arguments about diversity that take place entirely between groups of white people, I can’t help but think about how twisted things have gotten. When I see sites suddenly care about racial issues when something horrible or untoward happens, and the paucity of their coverage outside of controversies…well.

I’ve spent the past few months listening and reading instead of contributing, and I feel like Top 10 lists of characters who are X aren’t good enough any more. Suggesting that white creators writing black characters is an increase in diversity in the industry only works for a very, very specific definition of “diversity.” Essays comparing Malcolm X and Magneto are increasingly corny as time goes on. Only paying attention when someone says or does or writes something racist is craven. Editorials that have no substance beyond “This exists” or “This happened” should be kicked back to the freelancer until they can add some real commentary to it.

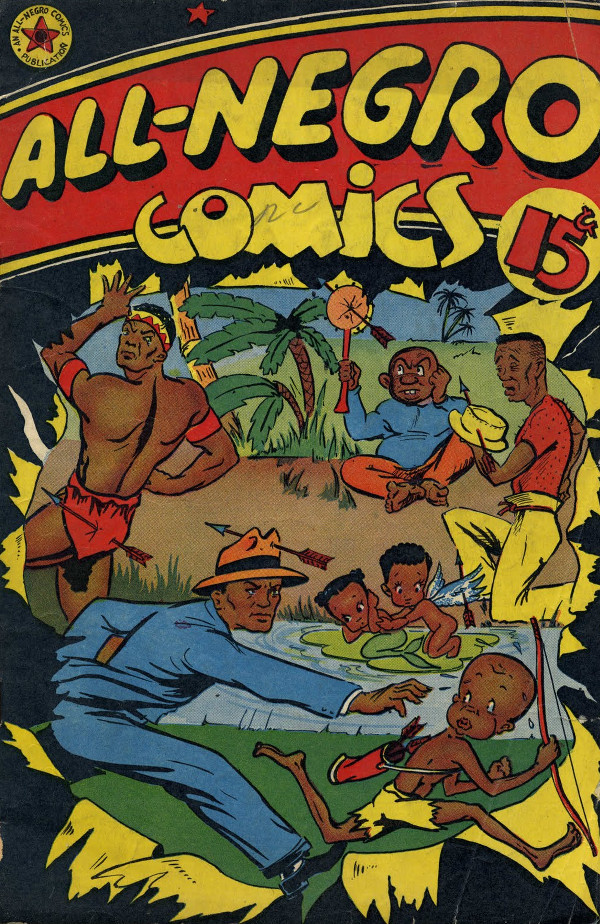

Lois Lane turned black once? Ha ha, that’s great man, but let’s talk about the Big Two having a frankly pathetic number of black writers since forever, why we’re more interested in character diversity than creator diversity, black history in comics, Milestone, ANIA, Grass Green, Jackie Ormes, George Herriman, Michael Davis, All-Negro Comics, Matt Baker, Marguerite Abouet, and more things that we’ve been missing. If something goes down, instead of racing to tell people it went down, wait a day and think about it before you put pen to paper. Stop worrying about first and start aiming for being better.

We need educated commentary. We need people who are capable of putting the things creators say or characters do in their greater context outside of comics. We need to be able to interrogate our own biases, take a new look at the history of comics, and be willing to talk about the weird gaffes outside of making theoretically hilarious jokes about it. We’ve got to pay attention outside of February and controversy that makes you feel good for not being as bad as whoever.

We let Alan Moore talk about how he broke ground in comics by introducing the first interracial marriage in Tom Strong, but we’ve failed to point out all the other interracial relationships in comics in the decades before he wrote Tom Strong. The marriage bit is new, possibly, but is that such a huge leap forward when nine times out of ten your non-white cape comics characters are in interracial relationships?

I appreciate the people who currently go to the mat for diversity in comics, but that kind of lapse is embarrassing. We have to be able to separate fact from fiction better than we have so far. Vet everything before you put it out there.

We’ve got to demand more. What we’ve got isn’t good enough.

Steve: Your own writing remains some of the strongest in comics, on sites including 4thLetter and ComicsAlliance. One of the things I would say is most notable about your writing is your primary focus is on art, rather than script. How do you approach comics? Do you think you do engage firstly with art, and then with writing?

David: Thanks for the compliment. I’d be remiss not to point out some of the people who made me a better writer out of pure jealousy, like my brother Gavin Jasper, fellow comics blog class of ’05 alumni Tucker Stone and Sean Witzke, Cheryl Lynn Eaton, the Funnybook Babylon gang, Jog, and Graeme McMillan. If my work is any type of strong, it’s because I surrounded myself with and read the work of people who are better than I am.

I would actually quibble a little with your description of my focus. I’ve written a couple reviews that were entirely art-centric, but my focus is on storytelling, rather than art unto itself. I wrote a review of a Conan comic a while back that was focused entirely on how the artists portrayed the sex and violence in the book and barely mentioned the writer, but even that was approaching the work from the perspective of artist-as-storyteller, instead of writer-as-storyteller, which is the default mode of most comics reviews.

I just consciously try to avoid giving the art short shrift, and that may be why you feel I’m focused on art. But really, I try to look at the comic as a whole, not just one aspect or another.

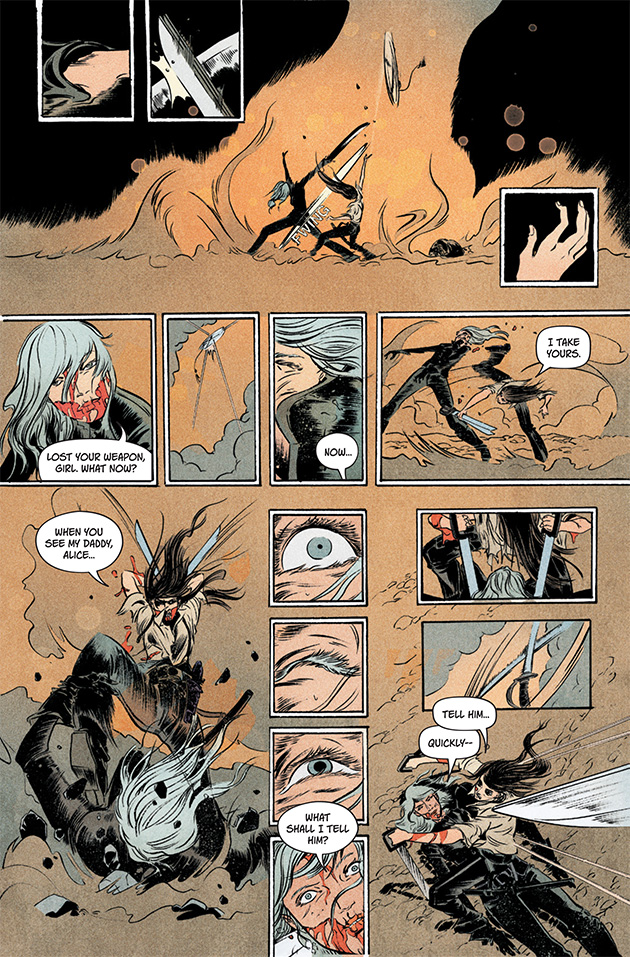

Art by Emma Rios

The comics review formula is two or three paragraphs on the writing, one limp paragraph on the art, and then a pithy outro. That’s bad writing, and doesn’t reflect what a comic book actually is. So I made a conscious decision to start digging into the art in my own work because it was the type of review I’d want to read if I weren’t the author. It’s not at the expense of the script at all, I’d say, because it’s still about the story of the comic, and the story is script+art. Watchmen’s not Watchmen without Dave Gibbons, which is a mistake I’ve made in the past. So to an extent, I pay extra attention to the art as a corrective for my own biases or poor training, but I’d argue I’m going for something more holistic than focusing on art.

My approach when evaluating a comic is basically “How do all these pieces fit together and why do they make me feel the way I do?” The script, the line art, the lettering, the colors, and sometimes even the paper quality (gloss vs matte on reprints is a big deal, for instance) all matter when discussing comics, and from there I can figure out what I want to discuss as a critic, whether it’s Inio Asano’s expressive and doughy faces, Brian Azzarello’s wordplay, Garth Ennis’s facility with dialogue, or Frank Miller drawing the best bodies in motion in all of comics.

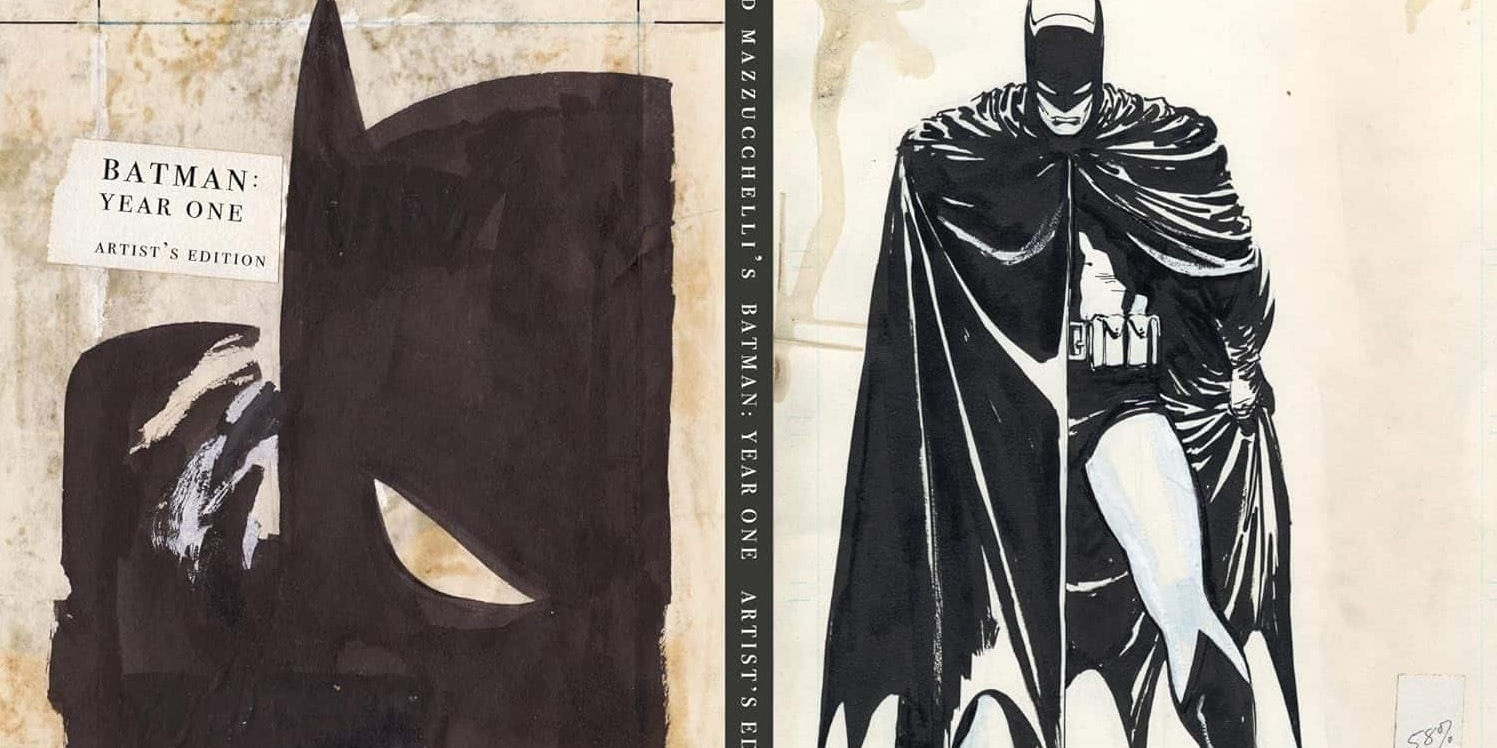

My preferred comics review, my Platonic ideal of a David Brothers Review, would tie together everything and paint a picture of why a comic works for me the way it does. One of my last things for ComicsAlliance was a long piece on Quitely & Millar’s Jupiter’s Legacy where I just dumped everything I could come up with about the book onto the page. I don’t know that I hit the mark I wanted to, but I definitely approached it with the idea that comics are actually a maelstrom of words and art, instead of words and then art. I tried something similar with Frank Miller’s Batman, which was exhaustive/exhausting. I like how that one turned out, though.

And obviously if you’re doing a deep dive on a slice of a book, your focus will be different, but if you’re doing a general review of a comic and not paying anything but cursory attention to the art, you’re half-stepping.

Steve: You’ve written about your own engagement with art, as a reviewer. What advice would you give on critiquing, reviewing, understanding art? Do you think it’s a case of just being honest to what your response is, and doing your best to put that into words and definition – you can be ‘correct’ with time, but firstly you should be honest?

David: The only advice I’ve really got is “Just do it.”

I get that you’re scared because you aren’t trained in art, but you don’t have to be a trained comedian to know when a joke’s not funny, and you don’t have to have worked as a cook to know when a hamburger tastes like crap. No one’s expecting a detailed art class critique, just your thoughts on what you read, and if you read a comic? You read the art, too. You know what you like and you know what you don’t, and you’re a liar if that stops at “this is good” or “this is bad” or pointing out obvious things like “Eduardo Risso draws sexy girls.”

It’s totally about being honest about your response. What makes them sexy? (Their faces and their glares, not just their bodies.) What makes Kevin Maguire’s faces so good? (His characters mug for the camera, over-acting like they’re in a play or the way children don’t hold back with their faces.) What makes Emma Ríos’s fight scenes so good? (The sense of motion.)

Figure out what you like about it in your own words and put it out there the same way you would if you were writing how you feel about plot-oriented developments. I’m not going to say it’s easy, but I think the idea that art is so much harder to write about than script is a fake idea. It’s just different. The more thought you put into doing it, the better you’ll understand your tastes and maybe even art, and that results in a better finished product.

Steve: You’ve been writing about comics for several years now. How do you feel about yourself as a writer? Do you think your voice and perspective came through immediately, or did they take time to grow and develop?

David: Writing about comics is an art like anything else, and the more you do it, the more your voice evolves. That doesn’t mean it’ll get better, but it’ll change as your life changes. I had a voice immediately, and it was the voice I wanted at the time, but it isn’t the voice I have now or a voice I’m at all impressed with today. I started writing about comics in my very early twenties, and I’m pretty different now than I was then. I hope, anyway. If I still had the same voice, I’d straight quit.

The easiest way for me to mark my progress is by looking back at my Black History Month posts. I did 95 separate posts on 4thletter! under the umbrella of Black History Month, from 2008 to 2011, plus a few side projects on the subject at ComicsAlliance and for Marvel.com. The meat was always on 4l! however, and they were consistently the posts I put the most thought, time, and energy toward.

The 2008 stuff I started on a lark, and it shows. It’s mostly unfocused short pieces for each day of the month that related comics to black history, black culture, and black people. I spent a lot of time talking about black characters. In 2009 I wanted to get serious but had no idea what serious meant, and by 2010 I was into the personal essay and interview zone for what I dubbed Black Future Month. I talked to people whose work impressed me, I discussed my own perspectives on the subject at length, and tried to paint a picture of where things were and where they could go. Come 2011 I cut myself out of the equation and put the spotlight directly on black creators.

At this point, I barely write about comics at all any more, and I’m over using Black History Month for a spotlight. I think I’ll better serve whatever moving target it is I want to hit by doing a more thorough job of integrating that work into what I write about in general, because I think that paying close attention for a month let me get away with failing to write about black works I enjoy outside of February. I spend a lot of time reading and learning, and that needs to be reflected in what I choose to discuss.

My evolution wasn’t an accident. I can be harsh talking about other people’s work, but nine times out of ten, any critique I’ve lobbed in someone’s direction is something I’ve had to work through myself first, from ignoring artists as a matter of course to writing about race for garbage and self-serving reasons. I don’t know exactly what I want to be beyond “better than I am,” and hopefully I’m inching my way there.

It’s not a competition for me—I’ll never be as funny as Gavin, comprehensive as Jog, sharp as Sean, and so on. But I do compare the quality of my work to the work of others, and that pushes me to really interrogate what I do and why I do it. A lot of times, if I’ve gone dark on 4l!, it’s because I haven’t written anything that I feel is up to snuff. I thought Fruitvale Station was one of the sharpest movies to hit last year and I’ve been silent on it, because I haven’t been able to do it justice yet.

Though, in the past, the trick to pushing past that has been “getting over myself and ignoring my pride,” so maybe find another role model, kids! I want to be proud of what I’ve written, but I want to be excited by it, too. Hitting those marks can be tough, and sometimes you’ve just got to stop being afraid of whatever fake bogeyman you’re avoiding (“What if this one makes people turn on me?” is dumb, trust me!) and trust yourself and your talent.

Being a writer/critic is probably like this for a lot of people, or at least I hope so. Otherwise I’ve gotta find something other than feelings of inadequacy to keep my sword sharp! I feel a lot more comfortable with my voice now, and I’ve learned how to use it much better than I could even two years ago. I’m just constantly refining my approach and voice, turning my harsh focus on myself in an attempt to get better. I’ve gotten a lot better at liking what I write after I get some distance from it, too, which I used to be a rare feeling. I don’t think I’ll ever be 100% content, but I’m okay with that, too. I just need to trust my voice.

Steve: Following that, I hope it’s okay if I end by asking a question which plays on your understanding and participation in comics – who do you think we should all be looking out for in 2014? Which artists, writers, creators do you think are going to really break through this year and make themselves known? What is 2014 going to bring us?

David: I’m actually really behind on what’s coming out in 2014. Comics news can be kind of a drag, and there’s enough stuff out that if I just discover things through word of mouth, I’ll still have plenty of things worth reading. I’ve got friends on Tumblr and Twitter who keep up with that stuff, and I’m fine discovering things through them, by accident, or naturally, like seeing a listing on Amazon or a stray link on a site or something.

I am looking forward to a few things, but they’re either things I’ve pre-ordered or already enjoy. First, Retrofit’s full year subscription, featuring work by Box Brown, Sam Alden, Madéleine Flores, Zac Gorman, Josh Bayer, Antoine Cossé, Ben Constantine, Anne Emond, Niv Bavarsky, and Jack Teagle was a must-buy. I’m not super familiar with indie comics (or however you choose to define comics in this area) yet, and I’ve spent the past few months buying them just because friends liked them or they sounded interesting. So far, that’s working out. I got Retrofit’s fall subscription last year and it was great, and they’re offering a digital-only release this year, which is great-er.

Second, I got an early peek at Inio Asano’s Nijigahara Holograph, being published by Fantagraphics this month I think, and it was very good. I’m hoping a bunch of critics go absolutely ham on it, because there’s a lot going on. My first thoughts after finishing were how certain thematic aspects relate to similar situations in The Invisibles and Neon Genesis Evangelion, but thinking about what happens in that book for even a minute should yield some great essay ideas. I’m hoping to see a big roundtable on it.

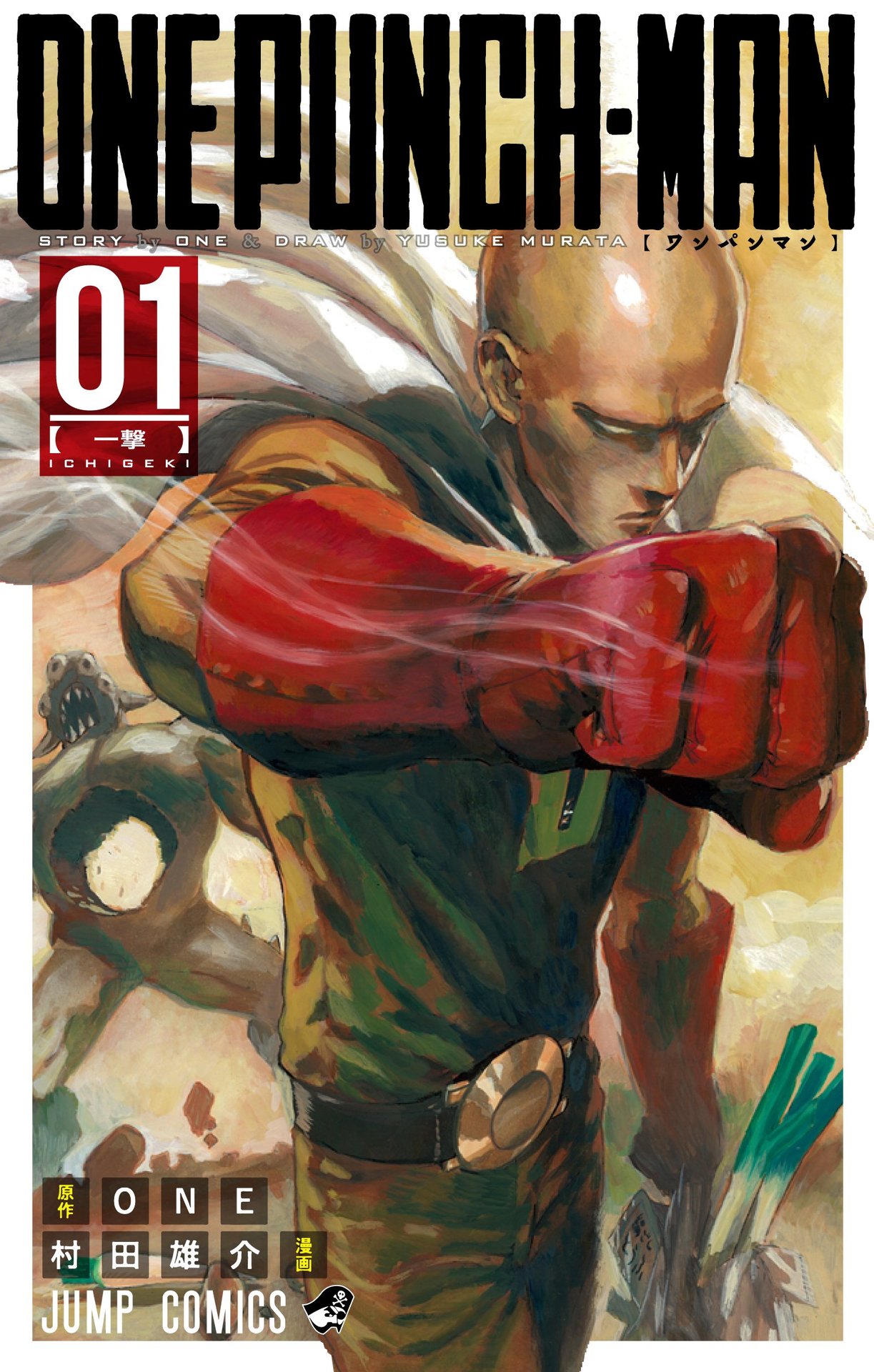

Third, I just re-upped my subscription to Weekly Shonen Jump, published by Viz Media. For my money, it’s the best anthology in comics right now, thanks to works like Eiichiro Oda’s One Piece, Yusuke Murata & ONE’s One-Punch Man, and various other works. I don’t love every strip in the book, but it’s an anthology—you’re not supposed to. Nisekoi is immaculately drawn and frustratingly boring, but One-Punch Man is one of the best cape comics I’ve ever read, and Oda is doing some absolutely devastating things with foreshadowing in recent tales. Even if WSJ only had these two series, it’d be worth the money, but there’s always a fistful of other books I dig in there, too. I imagine and hope that level of quality will continue throughout the year.

Past that, though, I just take it day-to-day. If I see something hot on Tumblr or if people are pushing something on Twitter, I’ll pick it up. I used to be really obsessive about this kinda thing, I used to have to know what was the book of the year six months before it streeted, but nowadays it’s just like…why rush? It doesn’t make the book come out faster and it sets up expectations in your head. Take it easy, sit back, and enjoy the surprises.

–

Thank you very much to David for his time and answers. You can find his writing at 4thletter, and at Comics Alliance – you can also find him on Twitter right here.

Man, I could read David Brothers riffing on comics all day (and very nearly have). Great interview piece here, Steve.

Call me biased, but I have to say this is probably THE most important piece I’ve read on The Beat. Thank you Steve for stepping up the game and for unleashing David Brothers. His passion and observations hit the mark on where comics are and should be going.

I agree wholeheartedly that the *comic industry* is often seen with such a narrow focus in criticism among a lot of sites and among many readers. It will take years, or another generation or more, before we can call our medium just *comics*.

I would love it when comics reach the awareness of a film I see at the theater. I don’t worry if a film is made by Sony, Universal, Lions Gate, WB or whatever. I go to see the film. But comics are kinda stuck in this DC comics vs. Marvel Comics vs. Indy Comics vs. Manga comics, vs. Webcomics, etc. — when in fact they are all comics. It’s all the same medium. But as Brothers said, the larger companies are grandfathered in and making billions of dollars at the box office and spin-off products.

Don’t get me wrong, I applaud that. I used to bitch and moan about the lack of public awareness of comics less than a a decade ago. Times have changed. Now we got comic awareness coming out of our ears.

But the benefits from that success isn’t complete across the board and some folks have taken it as an opportunity to draw lines in the sand and entrench their personal beliefs. We’re not doing ourselves any favors by doing that. We should all be working toward a wider understanding of comics. Not that we have to like and love all comic genres, I’m not fond of some movies but I don’t dismiss them as valid films — I just say they’re not movies for me.

I would KILL to do more straight drama , romance, young-audience comics, but I fear they will just die in the direct market. At this point my career is more about personal ideas than commercially viable ideas.

“… non-Big Two stuff in general is going to be secondary for a long time, no matter how good or original it is. But the more people pay attention, the better things will get, right? Hopefully. I think we’re moving in that direction, and hopefully we can sustain that momentum.” — Brothers

God, I hope I can sustain myself to live and work long enough to see that direction take shape.

A very good interview.

Thanks for posting it.

Good to see David Brothers talking comics again. He really drives home the need to fully engage with comics as comics instead of just as stories or just as art.

“Steve: What do you think websites – like The Beat – should be doing to encourage diversity?”

We’re trying our best at TheNerdsofColor.org

Wow. That was just.

Wow.

More please.

Comments are closed.