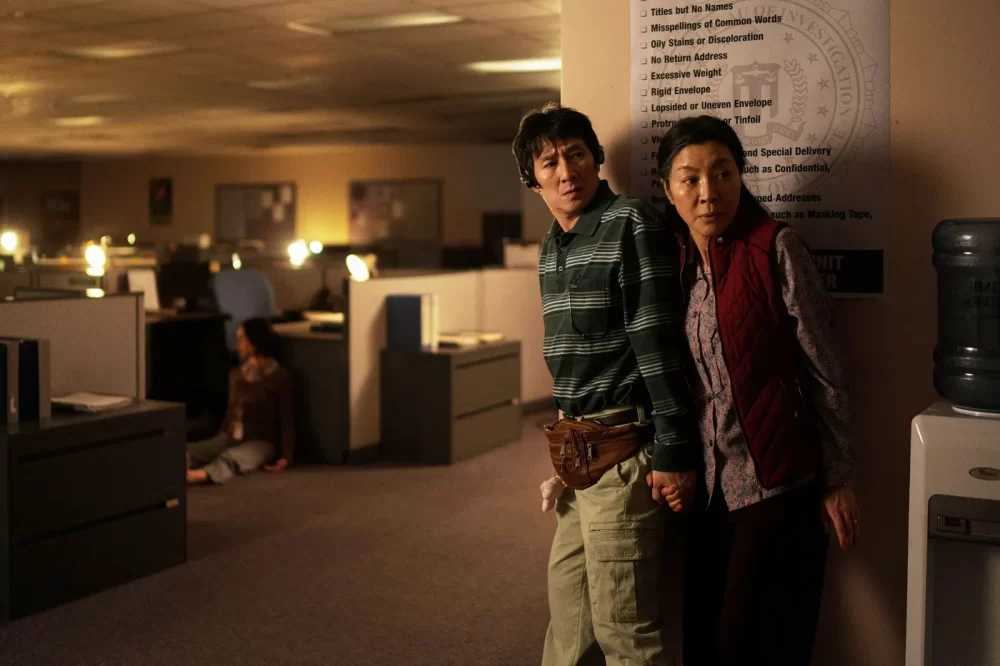

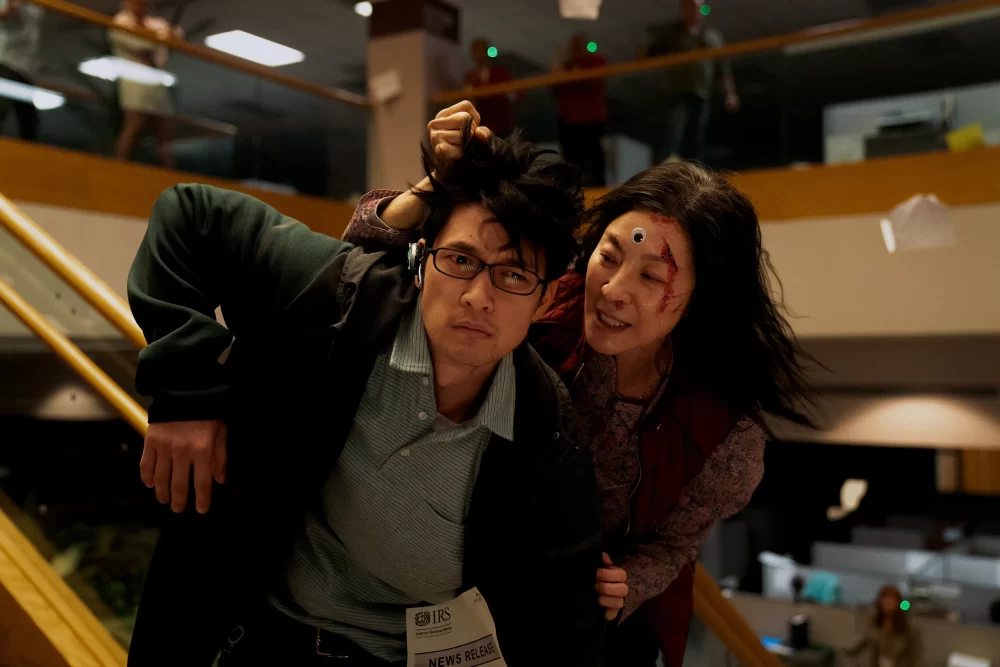

What would you do if you could live a different life? One where you’re stronger, more confident, richer, and more famous? The characters in Everything Everywhere All At Once explore just that concept. Directed by the Daniels, Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert, Everything Everywhere is about a woman named Evelyn (Michelle Yeoh) who must explore the multiverse in order to save it, all the while trying to balance a tenuous relationship with her own family. Her family consists of her husband Waymond (Ke Huy Quan), her daughter Joy (Stephanie Hsu), and her father (James Hong), who has just come to America from China.

Everything Everywhere is the Daniels’ second feature film after Swiss Army Man in 2016 and tells a story about a normal Chinese American family that is thrown into chaos when the multiverse is threatened. Bizarre, crazy, and completely chaotic, the film brings together themes of family, regret, and healing while wrapped up in a kooky hot-dog-finger-raccoon-chef package. We spoke with the Daniels about their new film and talked to them about how their film got made, the mindset behind the idea of multiverses, working with their amazing cast, and some of their influences for the film. Read more below!

Therese Lacson: So, I would love to know the impetus for the story because it was the wildest ride I’ve been on in a while, but I absolutely enjoyed it. Can you talk about how the story came together?

Daniel Scheinert: Yeah, it took six years, and a couple of 100 people. But it started with us having just made Swiss Army Man, wondering what we do next. And journalists, like you, being like, “Are you guys gonna do like a Marvel movie next?” And I think it made our brains go: what kind of action sci-fi like, what would we want to make? And we started chewing on this multi-verse jumping premise. Back then there was a moment when we decided it could be an ode to kung fu movies and that style of action, which we love. We could cast those actors that we admire. Then the family would be Chinese American, which would be something we hadn’t gotten a chance to explore in our work. That was when we’re like, “Let’s write that. I think that sounds exciting.”

Daniel Kwan: So this was our, what if we sold out —

Scheinert: It started as our sellout project, but then it became like…

Kwan: I still think we sold out.

Scheinert: Yeah this is our sell-out project. We did it for the money! [Laughs]

Kwan: The fact that everyone’s liking the movie meant we didn’t do a good enough job.

Scheinert: Yeah, we wanted to piss people off like last time.

Lacson: I mean, you worked with the Russos on this, so I was definitely gonna ask you something along those lines. I’m glad you just saved me the trouble.

So, obviously, when you’re talking about a story like this, you don’t want to get too in the weeds when it comes to traveling through universes. How did you come up with this unique and wacky version of connecting yourself to your different multiverse forms?

Kwan: We both grew up loving Kurt Vonnegut and Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, and that kind of stuff. So, there was always this absurdist bent on how we like to appreciate sci-fi. And then we grew up and Charlie Kaufman started doing a lot of sci-fi stuff. We always wanted to create something that was very playful and absurd, but that was still grounded in the ideas of quantum physics and probabilities. But then, one day, I watched a double feature at the New Beverly in LA, and it was Fight Club and The Matrix, and I remember was coming out of that being like, “Those movies are amazing. They’re still just the most fun.”

Scheinert: Was it in that order?

Kwan: No, it was The Matrix then Fight Club.

Scheinert: Oh my god, your brain must have been fried.

Kwan: I know. So The Matrix was so much fun and then Fight Club was just so nihilistic, both of which kind of fell into this movie as well. And so I was on the way to a wedding venue, because me and my wife, my fiancé at the time, were trying to figure out where we’re gonna get married. We were driving up to Big Sur, and back and forth along those switchbacks, I just started imagining a premise where you can connect with other versions of yourself, but it’s actually a blessing and a curse. You get their power, but then you get distracted and have existential questions arise every time you do it. So I just imagined, what if we just played in that sandbox? And the idea kind of grew from there.

Lacson: How interesting. Well, Daniel Kwan, as a Chinese American myself, one of my favorite aspects of the script were those dialogue moments where the family is code-switching between dialects and languages, which felt very familiar to my own family. Can you talk about writing those scenes and figuring out the dialogue for those scenes?

Kwan: My dad’s family’s from Hong Kong. My mom’s from is from Taipei. So the same thing as you, I grew up in this weird world where I couldn’t even communicate with my grandparents on my dad’s side, because I only knew Mandarin. But even the Mandarin I knew was not enough for me to fully communicate with my mother’s side, and so my mother would have to try to translate. But even my mother’s Cantonese is not that good, and my dad refuses to speak Cantonese. He moved to New York when he was six, so he just absorbed English and doesn’t speak Cantonese. So, it was very messy and complicated.

But we realized it was a great opportunity to create another barrier between our characters because this is a movie about people living in different worlds, and different universes. That’s the idea. Everyone’s talking past each other. Everyone thinks they’re in a different movie. Everyone thinks they’re the star of their own movie. It’s different genres, it’s very messy. The fact that the language barrier created another opportunity for them to all be in different worlds and talking past each other was really exciting.

And then, for the actual writing of it, my Chinese is pretty terrible, but I can still hear my aunts and uncles talk and hear my mother talk. So I would just italicize anything that I knew I was going to turn into Mandarin. And a lot of that Chinglish was designed but in a very rudimentary way where I’d point out okay, this part is Cantonese, and then whenever this is italicized, that’s the Mandarin part.

Scheinert: And then our producer, Jonathan Wang, has a very similar background to Dan’s, but speaks better Chinese, so he helped us with a pass. And then Ke Huy Quan’s wife turns out to be the loveliest lady on Earth, and she speaks very fluent Cantonese and Mandarin. So then she and Jon worked together. Jon was very good at the Chinglish and she was very good at just full-blown eloquent Chinese, making sure it doesn’t sound like Americanized dialogue.

Kwan: It really came together when we did our table read with all the family of actors, Michelle, Ke, Stephanie, and James Hong. We read the whole thing out loud, and we would constantly be like, “You know what, that’s not how my family would talk.” We would rewrite it together. And someone would say something, and we would all laugh because we were like, “Yes! That’s exactly what my mother would say.” I think that made the whole thing come alive.

And the finale, the way it all wraps up, I think might get lost to English-speaking audiences. The final speech that Evelyn gives in front of her father and Waymond and her daughter starts in English so that she can communicate with her daughter, moves to Mandarin so that she can communicate with her husband, and moves to Cantonese so her father gets pulled in, and then ends once again in this Chinglish space, mostly English, almost as a way to pull it all together. So even in the structure of her speech, we try to be a metaphor for how she’s trying to pull it all together.

Scheinert: When Michelle first read it, she was like, “What are you doing? Why? My monologue switches languages four times!”

Kwan: And we were like, there’s a specific reason for each switch!

Lacson: I mean, I loved it and being able to see so many of those layers. And speaking about the talent in this film, not only did you get to work with Michelle Yeoh, who is obviously a legend, but working with Ke Huy Quan and James Hong. And also working with the new talent of Stephanie Hsu. Can you talk a little bit about how that experience was?

Kwan: We could do a whole interview about each of them.

Scheinert: We got so lucky with each of them. And each of them was perfect for the role that we wrote, but then they made it their own. It’s one of my favorite parts of the process when someone is cast and you get to sit down and talk to them about what did the character mean to them. Did anything bump them? What is their relationship with their family? And then getting to cater the parts to each of them. So, by the time we were shooting, the character was no longer mine, it was there’s.

Kwan: One of the things I really like about looking at this cast is, this movie, in a lot of ways, it’s about taking our preconceived ideas of things and exploding them, turning them upside down, and showing the depth and the multitudes that every one of us contains. Especially when I’m talking about Asian American immigrants, whatever. Looking beyond that, I just see untapped potential that is finally fully revealed. You look at Michelle Yeoh’s whole career, she has done so much. And yet, when she finally got the script, she said she was so moved by the fact that someone was finally going to let her show off everything she was capable of. I find that amazing.

Then you look at Ke Quan’s story where his career was cut short because no one wanted Asian guys in their movies unless there was a side character or a joke or whatever. So he had to disappear for a while. And now when you see him in this movie, one of the biggest things that we hear from people is just anger, people are angry that he’s never got to show off what he was actually capable of. It’s really beautiful that he gets an opportunity to show off all of what he can do, and so well.

Then lastly, the same thing is true with James. James has been in 100, 300, 600 movies. He’s never really got to do too much drama, mostly it’s comedy or voice acting, and he does an amazing job, he’s got such a specific voice. Yet, he was able to do this really beautiful moving scene about letting her daughter go. And at the end of the movie, I think that’s like really beautiful for him to finally show off that side of him.

Lastly, with Stephanie Hsu, we knew how capable she was because we had auditioned with her and worked with her. But the rest of the world doesn’t know. And even our financiers, like the money people, were like, “Can we find a bigger actress?” And we’re like, I don’t know if we can find — sure, maybe, maybe we’ll find someone more bankable. But no one’s going to pull it off like her.

Scheinert: Her audition was crazy. It was really fun.

Kwan: She can show the people around us, yes, she can be the star of this movie, and she did a great job.

Scheinert: And they better not take her for granted like they did Ke! Treat her better!

Lacson: I agree! So I loved in this film we see an homage to Wong Kar Wai among other homages, and he’s one of my favorite directors. Can you talk about some of your influences as filmmakers when it came to shooting this project?

Kwan: Too many of them.

Scheinert: Yeah, there’s so many, and some of them became helpful shorthand for the audience to differentiate the universes. Where we were like, “Okay, we’re gonna lean into genre with some of these.” Getting to play with the aesthetics of Wong Kar Wai‘s work was so fun, and our cinematographer was like, “Please, please, please, let’s do that.” Like, I want that genre.

Kwan: A lot of it was just selfishness because we wanted to play in these worlds. I always separate the references into two categories. There are the overt references that you see on the screen, like Ratatouille, The Matrix, and all that stuff. But then, I do think that the more important references for us as filmmakers, were the ones that like, and showed us that movies didn’t have to follow a formula, that broke the rules. All of that pop culture stuff could be really pandering, but because we filtered it through these other lenses, I think it kind of transcends just references or even homages.

Scheinert: Sometimes people will be like, “Your movies so weird. How did you know it would work?” Then I think about the anime films that we love and are inspired by, and we’re like, “Oh, they’re much weirder.”

Kwan: Yeah, some of that stuff, and Satoshi Kon‘s stuff is obviously really inspiring. And then Mind Game by Masaaki Yuasa, that finale is one of my favorite 30 minutes of cinema ever.

Scheinert: Then we both really loved Holy Motors, that French art film, where every 10 minutes, it’s a different movie. And somehow it’s not boring at all.

Kwan: And there’s no narrative, but they don’t care

Scheinert: Watching stuff like that is so freeing, being like, “Oh, that can work?”

Kwan: Yeah, and that’s the stuff I think that really is in the DNA that not many people will know at first. But that’s the stuff that drives the structural play.

Scheinert: Then if someone’s reading this article and they think, “I don’t know any of those [movies].” We structurally wanted the movie to have a rewarding, broad, gentle final feeling. We looked at Groundhog Day and It’s A Wonderful Life as movies where the main character loses all hope and then regains it, as references to say, okay, underneath it all, we don’t want it to be just weird for weird’s sake.

Kwan: Right, this is the 2020s version of those movies.

Scheinert: Yeah, it’s like a Christmas movie. It’s like It’s A Wonderful Life but for Chinese New Year and for Tax Day!

Lacson: Well I love that and I really really enjoyed the movie. I can’t wait to go see it again! I really appreciate you guys speaking with me. I’m gonna need the Racacoonie short film with Harry Shum Jr. ASAP. I need that in my life.

Scheinert: There might be an extended version of their song coming out one of these days!

Lacson: Oh my god!

Everything Everywhere All At Once is now playing in theaters.