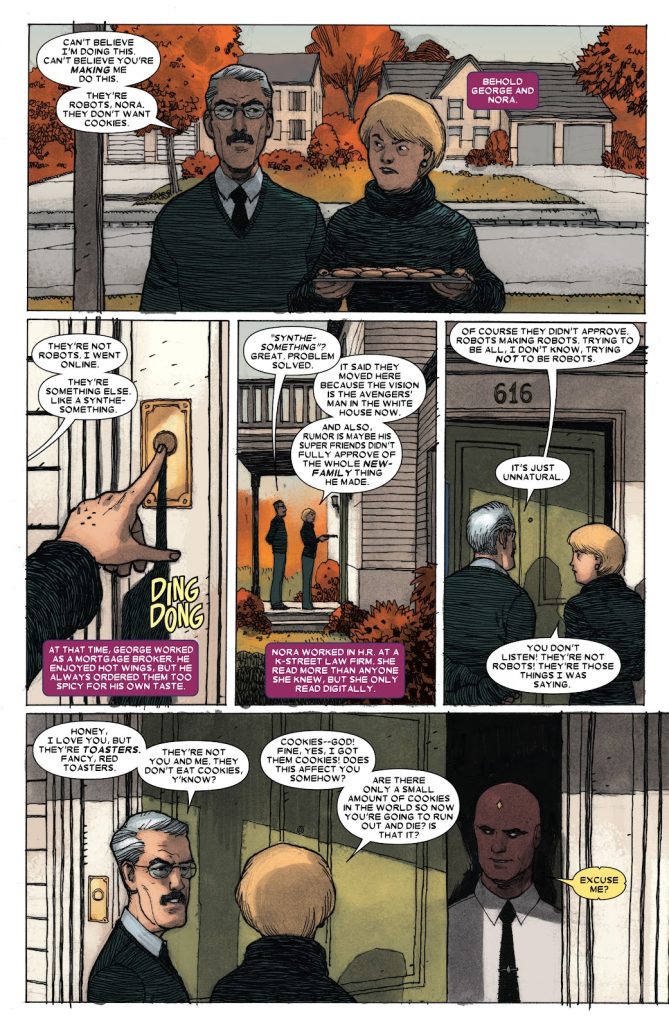

“They’re robots, Nora. They don’t want cookies.”

There’s an adage from Leo Tolstoy in Anna Karenina that’s oft repeated in regards to families, that “all happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way”. There are other applications and interpretations that follow-on or precede the adage, stemming from an idea that there are many ways to fail a set situation, but only one to find success, in everything from mathematics to ethics. Some will dismiss that happy family as boring, especially in a narrative form, but I’ll set aside that discussion for some other time. What does intrigue us more readily is the drama, conflict, and salaciousness of the unhappy family. Such is the case in The Vision from Tom King, Gabriel Hernandez Walta, Michael Walsh, Jordie Bellaire, and Clayton Cowles.

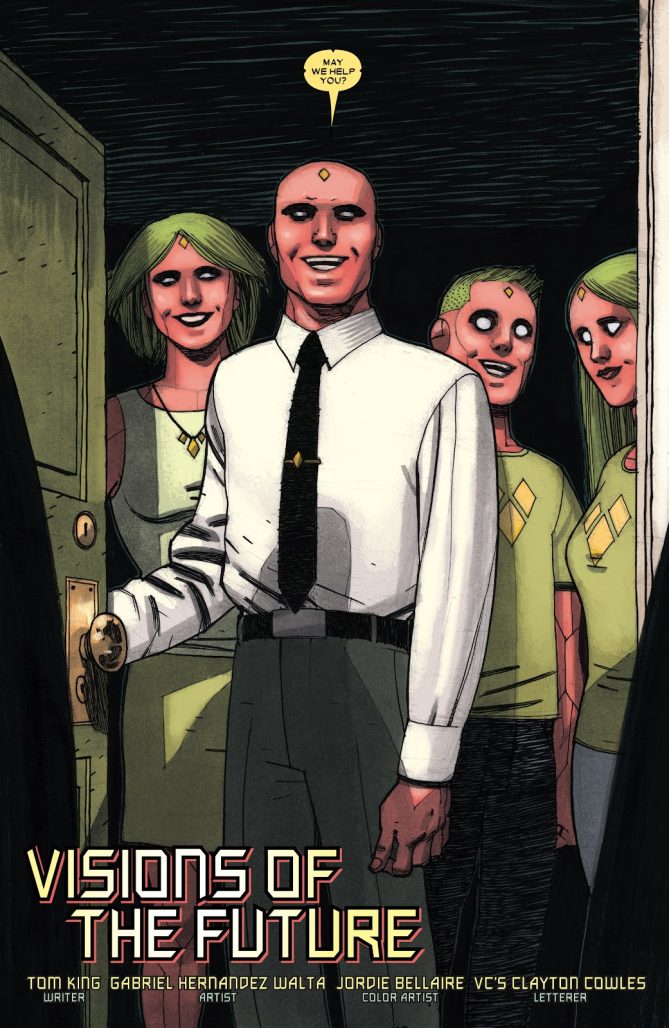

Before domestic bliss was ingrained as a recurring motif in much of King’s work (like in Mister Miracle, Batman, and Strange Adventures), he kicked it off with Marvel‘s resident synthezoid attempting to start his own family. The Vision introduces us to his family, Virginia, Viv, and Vin as they try to settle down to an ordinary life, going to school, hosting neighbors, and dealing with murderous uncles. Just like the archetypal American family in any Norman Rockwell painting.

There are a number of ways that you can look at the flaws in the design of the Vision’s family, which make it an interesting way to look at how a family can fall apart. Sure, you can put it in the box that a synthetic family is automatically destined to fail, that manufactured emotions in a verisimilitude of real life will naturally lead to strife, but I think that’s a simplistic view of the layers presented in the story. Although it’s a contributing factor, real or not, the actions carried out by the family, the fractures in Virginia and Vision’s behavior, were likely to happen regardless of whether or not they were synthetic. When you consider the situation of Virginia’s mental state, how a synthetic lifeform can suffer depression, and what she does for her children and family, it’s indistinguishable from what many a flesh and blood mother would do for their child.

There are examples of the characters falling into recursive loops when something negative happens contrary to their programmed optimal outputs, as Virginia keeps repeating words following behavioral breaks, Viv becomes obsessed with a classmate that actually treated her like a normal person, and Vin endlessly recites Shylock’s soliloquy from The Merchant of Venice, but is it really any different from an ordinary human who suffers a trauma? Reliving that experience over and over again, either stuck in the moment or trying to figure out how we could have taken a different turn. That latter sequence also speaking to whether or not Vin and his family still qualify as real emotional beings in the same fashion that Shylock explains that he too is a living being. And building out one of the central themes of this work, revenge.

The artwork from Gabriel Hernandez Walta, Michael Walsh (who provides the art for the one flashback chapter that deals with the Vision and Scarlet Witch), and Jordie Bellaire is atypical for superhero comics and I think that helps set this apart from ordinary superhero derring-do. Walta’s characters are stockier, with harder angles and increased hatching, that sets them apart from the smooth, rounded lines of a lot of superhero styles. Coupled with the softer pinks and greens of the Vision’s costume that Jordie Bellaire uses as the basis for the book’s color palette, there’s a kind of pencil crayon feel to the art that gives the impression of a dreamlike state. Or possibly a blueprint to those halcyon days of the middle America in that Rockwell painting. Enhanced further by Clayton Cowles’ letters, bringing a distinct digital voice to the family’s word balloons.

I also find that the rhythm of Walta’s layouts helps inform the overall feel of the story. In many of King’s other books, there’s an adherence to structure, particularly variants on 9-panel grids or 3-4 widescreen tiers. This doesn’t follow such a rigid structure, but Walta still gives the pages aspects of grids and tiers, that feel like part of a clockwork. That there’s still an internal mechanism, but it’s not keeping strict time, that’s it’s forming new patterns and sometimes it breaks. Much as the Vision would tell you that he’s keeping strict record, but that there are some flaws that he’s not willing to share. It manifests particularly beautifully in the ninth chapter, when more trauma falls.

The Vision from King, Walta, Walsh, Bellaire, and Cowles is a tragedy. It’s about a Pinocchio who fails to be a real boy, but perhaps in doing so replicates the realest aspects of the human condition. It’s a meditation on family, loss, grief, and sacrifice with an intriguing subtext of mental illness. This family is unhappy in a unique and yet universal way, beautifully realized in art and dialogue.

The Vision

Writer: Tom King

Artists: Gabriel Hernandez Walta & Michael Walsh

Colorist: Jordie Bellaire

Letterer: Clayton Cowles

Publisher: Marvel Comics

A super hero story like no other. He was created to kill the Avengers – but he turned against his “father.” He found a home among Earth’s Mightiest Heroes and love in the arms of the Scarlet Witch – but it didn’t end well. Now, the Vision just wants an ordinary life – with a wife and two children, a home in the suburbs, perhaps even a dog. So he built them. But it won’t end any better. Everything is nice and normal – until the deaths begin. Tom King and Gabriel Hernandez Walta confound expectations in their heartbreaking, gut-wrenching, breathtaking magnum opus – collected in all its Eisner Award-winning glory.

Release Date: January 10, 2018 (The Complete Collection)

Read last week’s entry in the Classic Comic Compendium!