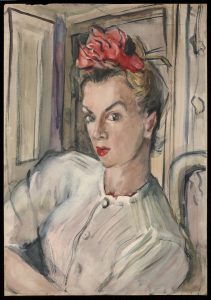

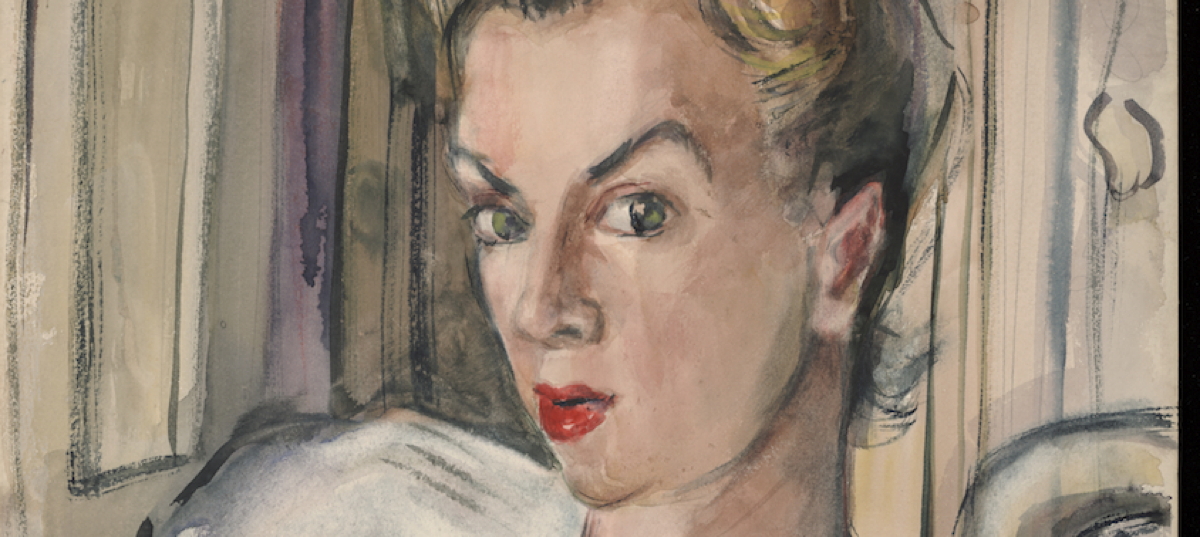

Tell Me A Story Where The Bad Girl Wins: The Life and Art of Barbara Shermund is an exhibit currently on display at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum. Shermund is a name that few will recognize today, but in the 1920s and 30s, she was one of the major artists at The New Yorker magazine, drawing hundreds of cartoons and nine covers. She was syndicated by King Features, contributed to Esquire, Collier’s, and Life.

The show is curated by Caitlin McGurk, who’s an Associate Curator and Assistant Professor at Ohio State University. She is also running a GoFundMe campaign right now to bury Shermund. After she died, Shermund’s ashes were never claimed, and only recently has her niece – who never met her aunt – claimed them. The story of a cartoonist being acclaimed and successful, but completely forgotten by the end of their life is something that has struck a nerve among many people in the comics community.

With the exhibit in Columbus Ohio ends March 31 and the GoFundMe campaign ongoing, I reached out to McGurk to ask about Shermund and this project.

Who was Barbara Shermund?

Barbara Shermund was one of the first female New Yorker cartoonists. She was a longtime contributor to Esquire magazine and a number of other men’s magazines. I discovered her when I first started working here. As the outreach curator one of my early tasks was to create a social media presence for the cartoon library and run a blog. I spent a lot of time just going through boxes of artwork in the archives. One of the things I came across was Barbara Shermund art and when I went to write about her, I was disappointed to find almost no information about her whatsoever on the internet or anywhere. I found some information about her in Liza Donnelly’s wonderful book Funny Ladies, about the history of women working for The New Yorker. She contributed about 600 cartoons to The New Yorker, multiple covers, but there wasn’t a lot of information. It sent me on this quest to figure out who this person was who could be making such cutting edge feminist commentary and such a huge body of work that I had never heard of – and that all of the other comics friends of mine have never heard of. I started researching her and I’ve spent time connecting with her remaining family members. None of whom ever met her themselves but one of which has taken an interest in her work and also happens to be a private investigator.

I was able to see a letter to her, I think it was from King Features, saying that they wouldn’t be buying things from her anymore that feature women drinking or smoking. Her voice was smothered and suffocated by the 40s and 50s and 60s. She started working for men’s magazines like Esquire and others and for whom she would draw other people’s gags. As a result her voice really dimmed and eventually disappeared. Her later work is funny and they’re great drawings, but they’re not what her work was. She died in 1978 and after she passed away, no one ever claimed her ashes. One of her husbands was remarried and the other one had passed away. She never had children. She was estranged from her family due to a sad history with her father and the death of her mother when she was young. When I connected with her niece Amanda Gormley as part of the research process, Amanda informed me that she had discovered Barbara’s ashes were never claimed. So she got them and as you know we are now in the process of trying to raise money to bury her finally.

The title is actually a caption from one of her cartoons. It’s not the cartoon we use for the main image for the exhibit, but I think it works. I wasn’t sure what to call this exhibit. That was a really difficult thing. This suggestion came form a colleague who was brainstorming with me about it and when she landed on it, I almost broke out in tears because it was just too perfect. It really captures everything from the scenes of her work to telling the story of this forgotten person whose work was considered no longer valuable once society changed. Everything about it felt really perfect. If I get to do a book, which I’m hoping to, I think I’ll probably stick with the same title.

The Billy Ireland is the largest collection of comics art in world, is that right?

It’s the largest collection in the world. We have over three million items. It’s hard to compete with that. We’ve been here since the 1970’s, which is also hard to compete with. There are a lot of libraries that are collecting this kind of material on the archival level now, but when we started that was one hundred per cent NOT the case. We were one of the only places doing it which meant that people like Will Eisner and Walt Kelly and Milton Caniff sent their stuff here and we’ve grown exponentially since. We focus on all material types. We collect comic books, original art, manuscript material, graphic novels, the whole broad spectrum.

The museum has had amazing exhibits and as you mentioned you have a lot of work from a lot of great people. Do you and others see your role and the role of the museum in doing exhibits like this one with Shermund that it’s important to not just display the work of famous artists, but to explore and reframe the history of comics?

That’s exactly what it is. Believe me, we did not think that when we announced a Barbara Shermund exhibit people would be knocking down the door to buy tickets to come to Columbus to get here. No one knows who that is. That’s part of the point. One of the things that we planned early on when we were moving into this new facility about five years ago was that if we were doing an exhibit of a major artist to try to balance that out in the other gallery with an exhibit of a lesser known artist. For example, the previous exhibit I curated was a Koyama Press exhibit. We did that at the same time as a Mad Magazine exhibit. The general public definitely knows Mad Magazine, but they don’t necessarily know who Annie Koyama is. It was amazing because it brought in these people who were here to see Mad who ended up discovering this whole other thing. That’s always been part of our effort.

For me personally, in my research and scholarship I really try to focus on unearthing the stories of forgotten cartoonists, be they women or men. I just think it’s important. With comics, until recently, there was no official comics scholarship. There was just fandom and fans were the scholars. You couldn’t get a degree and get this rounded out liberal arts perspective on comics history. Instead you get books or fanzines or articles written by a very specific kind of person about very specific areas of comics that those people were interested in. Most of it was older white males who were interested in superhero comics. There’s less in the canon about women cartoonists. I always go back to is the Angouleme controversy a few years ago where there were no female nominees for the Grand Prix Award. When asked for a comment the President of the festival said, if you look at the history there just aren’t women in it. I think that guy sucks, but maybe it’s not his fault that he thinks that – because the histories that have been written are not about women. If you look at what you have access to, you’re going to have this idea that no women worked in comics. It was male dominated, sure, but women were always there. I like to show that women have been working in comics since the very beginning. We try to highlight great women artists in our galleries any chance we have.

Of course we’re not celebrating Shermund because we’re discovering this amazing artist and this incredible body of work, but you’re running a Go Fund Me because of this horribly sad story that no one ever claimed her ashes.

It’s very sad. I will be very sad if this does not get funded. I imagine some people will read this and think it’s kind of crazy. This person’s been dead for a long time. But I feel passionate about this, and I think it does strike a chord with some people. A lot of people have been extremely generous. I just sat at my computer and cried the morning I launched it as these donations rolled in from cartoonists in my community and academics and I was really moved by the support. We have everything set up with the cemetery and permissions, so we just need the funding.

The GoFundMe campaign for the Barbara Shermund Burial Fund is going on now.

Comments are closed.