[An earlier version of this appeared in the Comics Beat newsletter, but it has been updated with more examples.]

By now, most of you have seen Ed Brubaker‘s comments on The Winter Soldier and his treatment over the character. He reveals that he’s made more money from his cameo in the film than for co-creating the character (with artist Steve Epting, who should also be part of this conversation.)

When Brubaker mentioned this in his newsletter there was some talk about it, and I heard from several people who pointed out that the Winter Soldier is a “derivative character,” one based on a pre-existing character, in this case Bucky Barnes, who was created by Jack Kirby and Joe Simon. Both Marvel and DC do have “character equity” contracts for when a character from the comics is used in media, but with a derivative character there is not an ongoing participation in the use.

In other words, Ed knew what he was signing. But that still doesn’t make it sit right with a lot of people.

It can’t be argued that the use of Bucky in the MCU wasn’t its own creative use — certainly actor Sebastian Stan brought his own special talents to the character and Kevin Feige and the Russo Brothers had their own vision for him.

But Brubaker and Epting created this specific use of Bucky — a character whose resurrection in the Marvel comics was strictly prohibited up to that point. (Uncle Ben is, I believe the only other character who had a permanently, truly dead rule for a while, although of course he has also come back in clone form.) Captain America’s beloved sidekick coming back as a deadly assassin with a covert ops past was both a unique interpretation of the character and very much of the post-9/11 time. And one that grew with added subtext over the years and spilled over into the films.

Reading Brubaker‘s tale, I’m reminded of many other classic stories of comics creators whose contracts betrayed them. And also, of the little petty things, like Brubaker and Epting not getting invited to the Captain America: The Winter Soldier after-party. I have a whole little folder of slights of this kind, and honestly, it’s just such a small thing and comics creators have such meager expectations that just getting to have some free snacks and hobnob with directors would probably make most of them happy.

I wrote a story about this topic almost a decade ago that still has some salient points. At the time, I wrote:

So, you adjust. A happy Alan Moore would have made more money for DC than an unhappy one. (The unhappy one has made a ton.) Think about the value of a happy Jim Lee, a happy Geoff Johns, a happy JMS. JMS was happy at Marvel…until he was unhappy. And SUPERMAN EARTH ONE made a lot of money for DC.

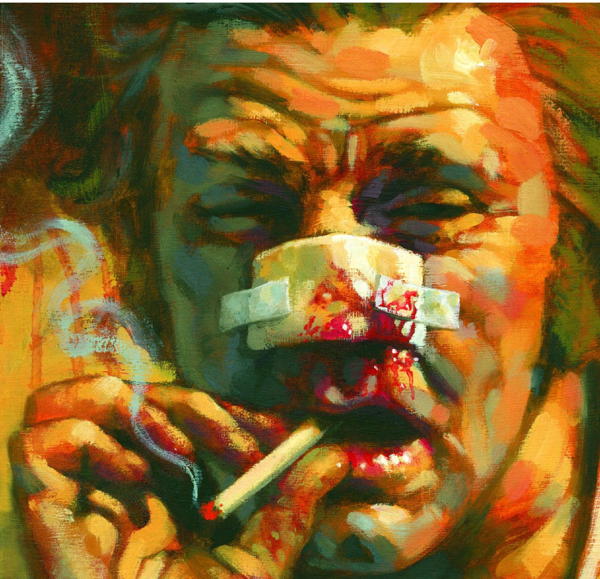

At one point, Marvel wanted to make Ed Brubaker happy. So happy that they “let” him and Sean Phillips create Criminal for their creator-owned Icon line, which was for a while a place for Marvel’s must valued creators to own some of their ideas. Bendis, Brubaker and, most notably, Mark Millar all published books through this line. Millar was a regular media factory there, with both Kick-Ass and Secret Service, the latter becoming the Kingsman series of films.

The Icon line dwindled away after Disney bought Marvel, and creators gradually took their properties to Image, where they had even more lasting control over their work. Millar sold his Millarverse to Netflix (where it is just beginning to appear) and Brubaker and Phillips have become a cottage industry of acclaimed and successful series. They’ve just shifted to a graphic novel first format with even more success: Pulp and Reckless were the #2 and 3 bestselling graphic novels of 2020 for Diamond last year.

Marvel as it exists — and DC in a different way — have no use for making themselves a long-running home for authors. Giving creators perks and extras to keep them happy isn’t seen as something that makes them money over the long run. (See the update below). They are IP factories, and by now, everyone should know this.

And yet, Disney does everything to make Kevin Feige happy, and Warners was happy to become a home for James Gunn when he was (briefly) exiled from Disney. The reason is the scale of money that the Feiges and Gunns make compared to publishing. But as I pointed out in my piece on Alan Moore, in the conventional publishing world, authors make tons and tons of money. You won’t see Scholastic doing anything to upset Dav Pilkey or Raina Telgemeier any time soon.

Just a few days ago, ComicsXF ran an interview with James Tynion IV which really works as a counterpoint for all of this. Tynion has, among all current creators, been using his mainstream success at DC to start carving out his own publishing world, much as Brubaker and Philips did. It’s a really a great interview that everyone should read in its entirety, but a few relevant quotes:

I am in a very privileged position to be able to do that. It’s something where, to be perfectly honest, I would not be able to bankroll a project like Razorblades at the same time as putting together the upfront costs for a series like Department of Truth without the bank role of Batman at my back. That’s something that changes and it’s something that I wanna build on. I wanted to see how each of these systems played off of each other. One big thing that bothers me a little bit about how the direct market side of the comics industry has worked for the last couple of decades, and I think there are some signs that this may be changing, is the fact that I think there are a lot of publishers out there whose core business model isn’t actually selling comic books. When the core business model isn’t actually selling comic books, and all of the benefits that creators received are contingent on how many comic books you sell, that’s why creators have to work at a bunch of mid-tier publishers to sort of add all of that up to equal a living wage and that sucks. It means that you have to spread yourself thin. I am someone who likes working a lot. My brain likes doing a bunch of different things, and I like doing a bunch of disparate things at once because I can sort of shift gears in between each of them, but I think that is the underlying philosophy is a lot of it is me.

Asked how the industry can improve he has an interesting take:

JTIV: I think there need to be younger people in decision-making positions. That is one of the most important things. Some of the tastes of the, even at the mid-tier publishers, are shaped by the sort of things that sold 10 years ago, which feels very recent, but actually isn’t all that recent in terms of the turnover of comic readers. Having done this now for a decade I’ve seen us cycle through basically three waves of audiences in that time, and I think there’s actually a new audience that’s picked up in the last year or two. But we cycle through audiences all the time, and you constantly have to shift. Each audience is coming in and asking for a different thing, and I think that we get caught in habit a lot. Oftentimes the young creators who are rising up have a better sense of what the audience actually wants then the people at the publishers.

Just as Ed Brubaker learned from the lessons of Alan Moore, James Tynion IV has learned from the lessons of Ed Brubaker. Tynion has the luxury of creating a Punchline for DC — knowing it is a part of an interconnected universe and grows from that — while creating his own stories at other publishers.

Creators keep getting smarter — and Brubaker is definitely among them, don’t get me wrong. He’s keeping his eye on changing industry trends and adapting to it.

And creators have the knowledge and freedom to do that as the industry currently stands, something Siegel and Shuster never dreamed of.

But wouldn’t it be nice if publishers addressed the needs and careers of creators as part of their business plan and not a perk to be given and taken away whenever its convenient?

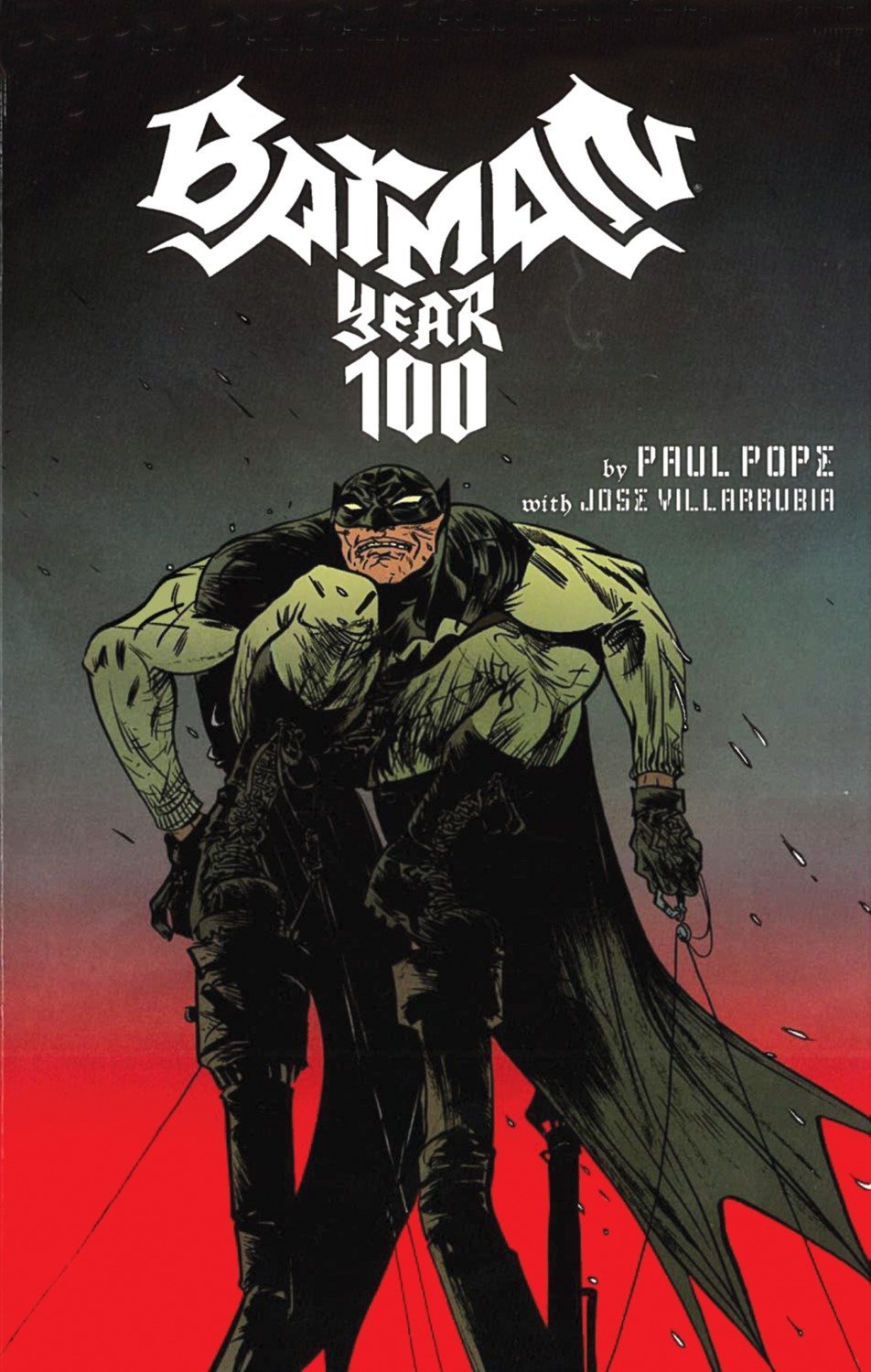

UPDATE: Yet another example of the Big Two’s lack of interest in developing authors hit me as I was reading this recent interview with Paul Pope in Hazlitt:

You released new editions of your breakout books Heavy Liquid and 100% with Image Comics—recoloured for a new decade and a new audience. What’s your attitude towards maintaining your backlist? I imagine it’s not just a question of simply keeping the titles in print.

When DC Comics moved to Burbank to be closer to their parent company Warner Bros., they went through their backlist and dropped a staggering number of properties. In my case, DC comics returned the rights to my Vertigo books, and I was able to take them to Image Comics. I consider those works to be cyberpunk, dystopian, near-sci-fi things and I think they still have an audience. The books have all remained in print, they’re published overseas, and those books are able to carry over as a placeholder as I’m finishing my new stuff. I’ve been out of the public eye for a while, just working—stealth years—and I got trapped in the Hollywood maze for a little bit, so returning to the roots for me is getting back into comics again.

Pope’s Batman: Year One Hundred is still with DC — understandably — but the publisher has no interest in reaping sales of his other work, even though it’s related in tone. It’s actually very commendable that DC/Vertigo gave the rights back to the creators of so many works that they didn’t want to publish any more — I see a GN from Peter Bagge that he published at Vertigo is coming out in a new edition from another publisher this year, to name but one example. But any aspiring creator should take note of the fact that as nice and supportive as your editor may be, the Big Two have no interest in developing your career as a creator, even if it means sales for them. They are only interested in their own IP. Tynion seems to have observed and absorbed this lesson…and to be forging a very modern path between the options. I hope it works out for him.

Raina Telgemeier is one of the first “big names” to avoid periodical comics completely. Now, 10(!) years later, and kids graphic novels shelves are full of creators who have never worked for a comics publisher.

Pilkey transitioned from picture books. There is a growing overlap of GN picture books. (Basically, a 32-page hardcover comic book.) Sendak is the proto example. Wiesner as well.

Using Marvel and DC as journeyman training is smart. Learn the business, gain a following, then incorporate a studio and own your own work.

Image is the big name for genre work, but if PRH (Del Rey) or Macmillan (Tor) enter that market…

How does the Japanese manga market work?

Paul Pope’s BATMAN YEAR ONE HUNDRED is, of course, Out of Print!

So it’s Marvel dissing the creators, not Disney? I must admit I’m kind of confused as to who is mistreating the creators but it seems that absolute antithesis of what any company whose main money maker is their characters should be doing.

Interesting.

Isn’t it obvious at this point as it is for for me that the Winter Soldier would never have had the “career” it did have without the emotional impact of him originally being Bucky Barnes. If he had been a nobody, that story would have been utterly pointless. So this discussion about some of these writers pretending to be “Creators” when they are just rehashing and spinning the work that has been done before by proper ones just makes me want to facepalm really hard. Time for a reality check gentlemen.

In any case there is no confusion that this is work-for-hire for Marvel or DC, yet it did wonders for the Image guys and many more over the years as a launching pad. So why are we still talking about this really?

Comments are closed.