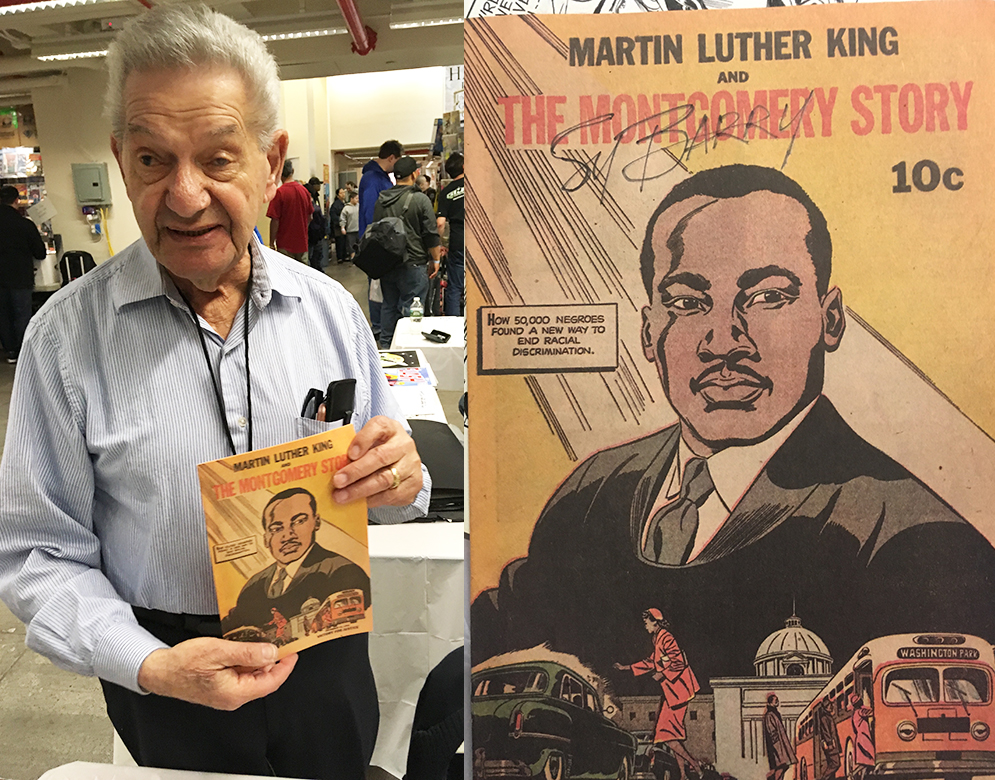

This last weekend, the Penn Plaza Pavilion in NYC was the home of the annual Big Apple Con, which featured a host of old school comics talent. I went to this event for specific goals. Foremost among these was my hope to finally clear up the long-standing mystery of who drew the famous and widely distributed comics pamphlet Martin Luther King Jr: The Montgomery Story. Because finally, Sy Barry emerged as a guest at the Big Apple Comic Con and indeed, he confirmed to me that it was he who drew the comic.

The thin color comic book offers a gripping depiction of the early days of African-American’s battle for civil rights through the use of peaceful civil disobedience. First published in 1957, it went through several editions and remained in print for years, because in grade school in the mid-sixties, I and many thousands of other children were given free copies of it. Venerated Democratic Congressman John Lewis of Georgia has repeatedly cited the comic as the inspiration for his three-volume March trilogy, the National Book Award and Eisner Award winning, N.Y. Times bestselling graphic novel series, a collaboration with his advisor Andrew Aydin and artist Nate Powell, which is published by Top Shelf. Lewis was one of the “Big Six” organizers of the 1963 March on Washington. Aydin made the comic the subject of his Master’s thesis for Georgetown University, a paper entitled “The Comic Book that Changed the World”. Here is an excerpt from Aydin’s thesis abstract:

“Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story is a comic book that has had a profound influence in both the United States and around the world. It has been uniquely successful in spreading the philosophy and discipline of nonviolent social resistance and serves as perhaps one of the strongest examples of the potential for comic books as a medium for inspiration.”

The comic is described on Wikipedia in terms of the very real life and death struggle faced by African Americans:

“Instead of the typical distribution network for comics in those days, which were newsstands, pharmacies, and candy stores, The Montgomery Story was distributed by the Fellowship of Reconciliation among civil rights groups, churches, and schools…(who) would distribute the comic to younger attendees as something to take with them and study. Some African Americans memorized and destroyed the comic to avoid being lynched for having it in their possession.”

Aydin and Sylvia Rhor investigated this important comic’s creation and were able to verify that it was co-written by Alfred Hassler (of the peace and social justice organization Fellowship of Reconciliation) and Benton Resnik. Still, Aydin and Rhor were unable to confirm the identity of the artist; their search sparked online speculations about who had drawn it. Cartoonist Eddie Campbell believed that either legendary golden age artist Sy Barry or his late younger cartoonist brother Dan Barry had been involved. Aydin tells me that he and Campbell worked with comics scholar Jim Vadeboncoeur, Jr. and the Digital Comics Museum to confirm this, but their attempts to contact Barry were unsuccessful.

In 2013, I expressed interest in ID-ing the artist to Aydin after seeing that the beautifully drawn and colored art job was uncredited. Aydin gave me a copy of the MLK comic, which I showed to a range of knowledgeable individuals, including Gary Groth and former N.Y. Times and The Nation art director Steven Brower, who was then engaged in writing a book about Johnstone and Cushing, the noted firm that specialized in comic strip advertising from 1936 to 1962. Again, among other candidates, the names of Sy Barry and his brother Dan were mentioned as possibilities. I did not know how to find Barry, though. Five years passed.

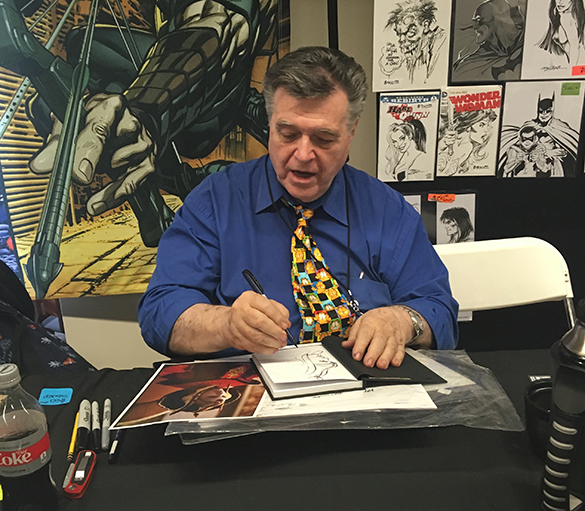

Now, the truth is at last revealed. Barry says that he was given the job by the Capp Studio, which was run by Li’l Abner cartoonist Al Capp’s brother, Elliot Caplin. Barry stated that his name had been on the cover of the very first edition of the MLK comic, but for later printings his signature was replaced by a text box. Barry would be later hired in 1961 as the artist of the daily/Sunday strip The Phantom, which takes place in Africa; it was a suitable job for an artist with such a solid grasp of drawing diverse likenesses of black people.

When I told Sy Barry of the long search for his identity that had been undertaken by Aydin and others and the importance accorded the comic by Congressman Lewis, Barry told me that he has very great respect for Representative Lewis and considers him to be the most worthy member of the legislature.

Barry, a master of dramatic visual contrast (inked “black-spotting”), is also well known for drawing Golden Age comic books for a wide range of publishers including Timely and DC Comics; for his tenures on the King Features daily/Sunday strips Tarzan and Flash Gordon; and for being genius cartoonist Alex Toth’s most accomplished and favored inker. He shared with me an anecdote about his involvement in the notorious incident from the mid-1950s when the famously temperamental Toth threatened to throw DC Comics editor Julius Schwartz out of DC’s skyscraper window because Schwartz was making Toth wait unreasonably long for a paycheck. Barry told me that he and inker Joe Giella (who was also at the con) were present for this fracas. The two succeeded in saving Schwartz by wrestling Toth out of the offices, they then “took him to lunch, where it took Toth nearly an hour to calm down”. One is tempted, though, to think that Toth’s fury might have formed a rough if displaced justice for Schwartz, who in those pre-“Me Too” days was never made to answer for his well-known pattern of sexual harassment of women who crossed his path.

I was faced with limited time and there were plenty of fans lining up to talk to the various guests at the con, so I didn’t get a chance to talk to Giella or take his picture, nor did I think to ask the wonderfully talented Golden Age artist Ramona Fradon about her thoughts on DC editors like Schwartz, although I did take her picture.

Fradon deserves a lot of appreciation for the quality of her work and as perhaps the only female artist to rise to prominence at DC Comics in the Golden Age up through the Silver Age and beyond. She has always always drawn with great fluidity and dynamism. Her beloved works include a long run on Aquaman and her co-creation, the incredibly bizarre Metamorpho and later in the seventies on Plastic Man, Super Friends and a series of moody, exceptionally expressive stories for DC horror titles. So she surely saw it all in her career, and yet she persevered in comics, eventually taking over the Brenda Starr daily/Sunday strip from 1980 to 1995.

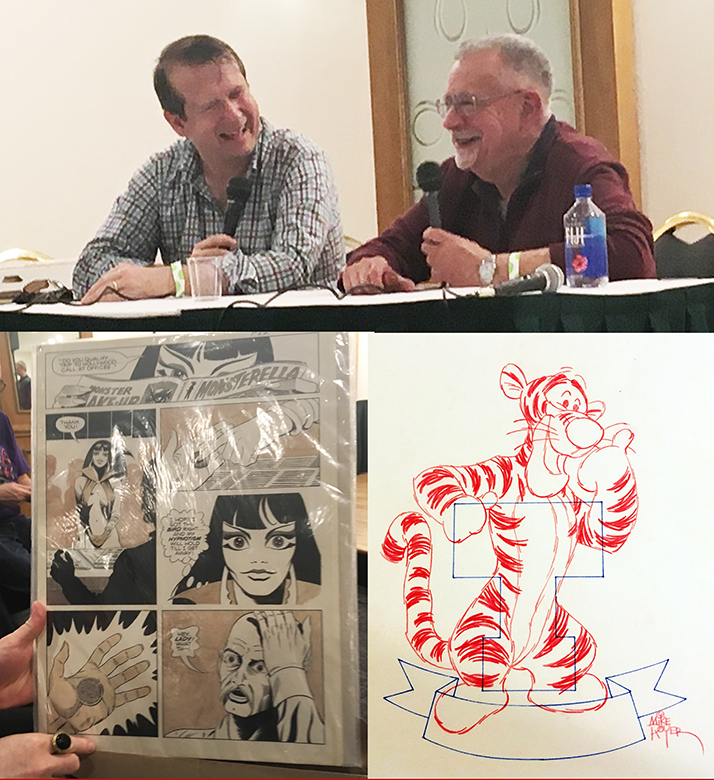

Another artist that I was fortunate to interact with was Mike Royer, who inked many of great cartoonist Jack Kirby’s most brilliant works, including the New Gods, which is being made into a feature film now by Ava DuVernay, the director of the Oscar-winning movies Selma and A Wrinkle in Time. I wasn’t able to get Royer’s opinion of DuVernay’s engagement, which seems to have enraged the usual horde of right-wing observers. I did ask him about his opinion of Argo, the Oscar-winning film about the CIA’s 1980 rescue of six diplomats who were hiding in Tehran at the height of the “Iran/Hostage crisis”, by their ruse of a fake film production seeking locations in Iran, which made use of the ornate drawings by Jack Kirby that Royer inked, that had allegedly been commissioned by producer Barry Geller for a film/theme park based on Roger Zelazney’s Hugo award winning novel Lord of Light.

I first contacted Royer about the Lord of Light art in 2002, when I told him via email of what Marguerite Van Cook and I had uncovered about the CIA’s usage of his and Kirby’s work for a zine article we were writing that would be reprinted in several venues, including a noted conspiracy magazine, Steamshovel Press. At that time Royer’s reaction was to tell me the story “sounds like bullshit.” However, Wired magazine optioned their version of the plot to George Clooney’s production company, which eventually resulted in the Argo film. The movie shows the CIA directly commissioning the work from Kirby, even asking him to amend his drawings to incorporate yet more exotic detail. Some have disputed this depiction, but questions remain because the Lord of Light proposal was publicly announced in in 1979, only a month before the CIA began their Argo operation, and a source close to the Kirbys claims that Kirby kept a copy of the CIA’s Argo poster in a closet, so it seems the artist knew of the operation before it was declassified in 1996 (Kirby died in 1993). At any rate, it is without question that the extraordinary quality of the Kirby/Royer artwork helped give the CIA agents enough confidence in their fake movie production company cover to pull off the escapade.

At the talk Royer did with Rand Hoppe of the Kirby Museum, I asked Royer from the audience about this; however he has yet to see the film and so, he remains unconvinced!

He did tell anecdotes about his dealing with eccentric publisher James Warren when Royer was one of the first artists to ever draw Vampirella, in a big-eyed syle that seems to anticipate the manga look. More recently, he has worked on product art for Disney, a job he loves. I bought a small drawing that he did of the Winnie the Pooh character Tigger. By the way, Royer also had a tale to tell about Alex Toth. In the course of telling how Toth had recommended him to Kirby as a good inker in the first place, when prompted by Hoppe to explain how he met Toth, Royer revealed that it had been he who first gave Toth the pile of copies of the Scorchy Smith comic strip art by Noel Sickles that Toth would famously distribute to so many of his cartoonist friends, influencing their approaches to their work.

More outstanding individuals I took shots of:

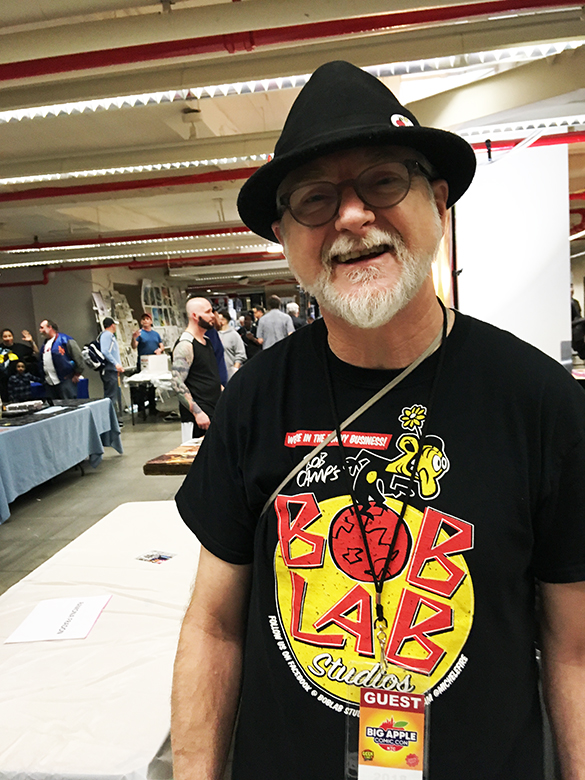

Bob Camp of Marvel’s Conan and The Nam; and TV animation such as Spongebob Squarepants—and a long run on Ren & Stimpy, whose creator John Kricfalusi is embroiled in some bad me-too controversy. But that has nothing do do with the very talented and Emmy-nominated Camp, who took over Ren and Stimpy after John K left following the first season.

________________________________________

Writer Elaine Lee shows off the gorgeous new hardcover revisions of Starstruck, her innovative graphic novel done in collaboration with the great comics draftsman Michael W. Kaluta and originally published by Epic Comics, Heavy Metal magazine and run as backups in Dave Stevens’ Rocketeer comics. These books feature many new pages in among the digitally recolored content. Highly recommended!

________________________________________

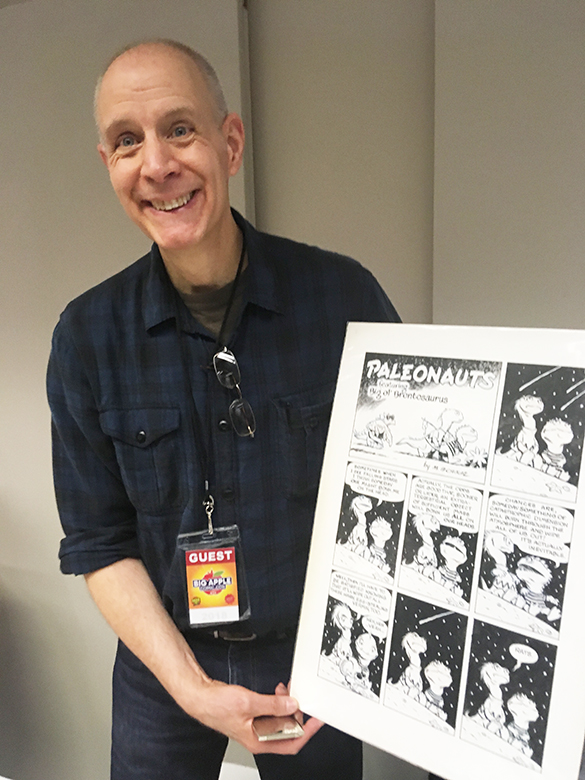

Mark Schultz, artist extraordinaire of Xenozoic Tales/Cadillacs and Dinosaurs fame and currently the writer of the Prince Valiant Sunday strip; and also my colleague in teaching our Marywood University graphic novel course.

________________________________________

I had the usual interesting but somewhat frustrating sort of conversation that I often have with legendary but contrarian cartoonist and occasionally very effective artist’s advocate Neal Adams. Adams told me he feels that young artists need to learn to draw from tracing photographs on a lightbox and I seriously beg to differ. We reached an impasse on that point, but his career has many indisputable high points, so no doubt we’ll argue it again in future.

________________________________________

And finally, I offer you a candid shot of a dealer, Ruben Miranda, an engaging character who has worked at a range of NYC shops including Forbidden Planet, the vast Koch Warehouse and other comics destinations of desire. At the Big Apple show, Ruben was functioning as the friendly face of the display put out by Harley Yee Comics of Detroit.

Th-th-th, that’s all folks!

Just one item on the great story in identifying Sy Barry as the artist on the Martin Luther King Jr: The Montgomery Story comic. The comic was released no earlier than 1958. This is because Dr. King is referenced as being a “29-year-old minister” which he does not becomes until his January 1958 birthday. it might have been written and drawn in 1957 in whole or part, but the age reference places it squarely in 1958 or afterward.

Once the Grand Comics Database is done working on its current website update, I’ll update Barry’s credits for this comic there.

Fradon deserves a lot of appreciation for the quality of her work

Run 3: I did make that statement up top, but also Fradon should get props for somehow persevering as an often lone female warrior within an astoundingly retrograde and misogynistic industry.

Comments are closed.