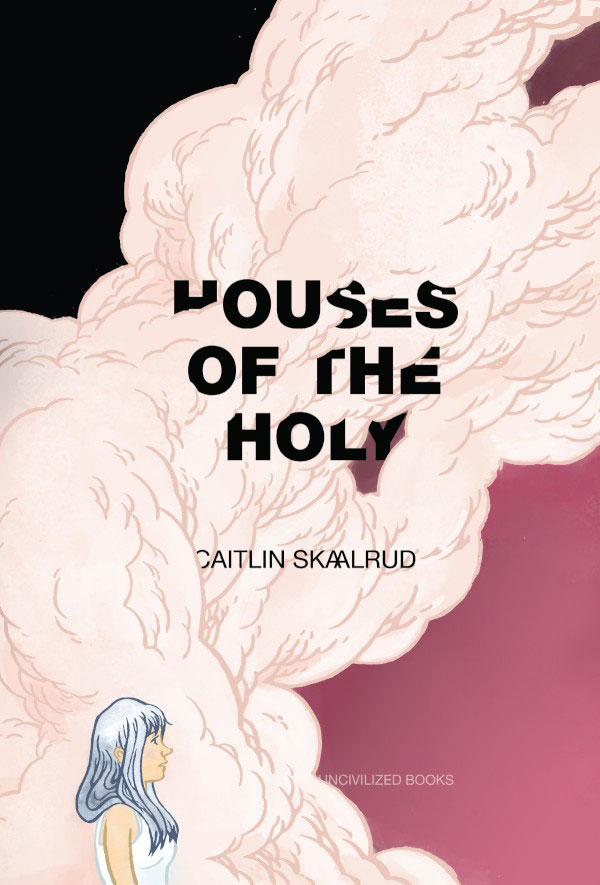

Houses Of The Holy by Caitlin Skaalrud

Caitlin Skaalrud’s Houses Of The Holy is, on its a surface, a psychedelic and psychological journey through the mind of a woman, with a heavy visual focus that carries a dreamlike surrealism of an almost Felliniesque quality. The idea, from the descriptions, is that this is a plunge into depression, and that may well be, given the spare and cryptic words that sometimes appear with the panels that hint at emotional turmoil and intense conflict. It’s less a reading experience than a plunge into someone else’s meltdown from reality.

I don’t usually do this, but Houses of the Holy moved me to look around at other reviews in the hopes of giving me some insight to the work that I could build on in reviewing it myself. Not that I wanted it spelled out for me, but I was interested in some sort of nugget that could operate as the beginning of a Rosetta Stone entirely dedicated to the specifics Skaalrud’s mysterious, poetic, apocalyptic work.

No such nugget exists, it seems, and I am left to my own intellect to try and decipher it.

While I can easily describe what happens in it, and maybe even why, I am less equipped to take the components of each image — from objects rendered in the image to the actions taking place in them — and interpret them beyond the obvious visual information you are being handed. And the reason for this is that I don’t live in Skaalrud’s head, the single factor that makes this so fascinating and so alienating at the same time.

I had reviewed an earlier release of this that corresponds with the first section of this expanded version, which struck me then as it does now for some of the resemblance to tarot cards, as well as Robert Wilson’s “14 Stations” installation, which laid out the stations of the Christian cross in the form of three-dimensional sheds.

Houses Of The Holy requires a lot more of me, and I plan to give it with further readings. It will do the same with you, and that’s a good thing, as its obscurity becomes more familiar, its details more vivid, and the experience of the meltdown so sublime that we all may realize that we don’t actually require any concrete of it at all.

In the end, I see Houses of the Holy as a series of coded messages, of collaged panels with different points of consciousness and time brought together, and moved along by snippets of response that are jumbled in their presentation. It’s an emotional reaction and summation, and trying to dissect anything too concrete, or too linear, is to refuse to accept the purity of what it is.

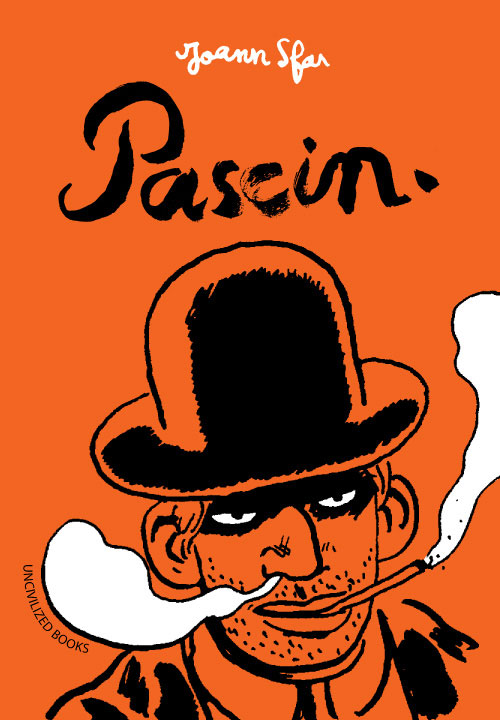

Bulgarian, Jewish painter Jules Pascin wasn’t known to me prior to this graphic novel, which depicts a sex-obsessed creative mind preoccupied with the low life. I have to make a confession before I even go further. I’m not very entranced by biographies of decadent creative types who revel in the muck of humanity as a way of cleansing their own despair, nor am I much interested in the contrast between the coarse lifestyle and the creative beauty. Given those facts, I was at arm’s length from the emotional content of Pascin’s story as it unfolded. What did bring me to the title is Joann Sfar, who’s offered some of the most exquisite comics work I’ve ever seen, though I also think pales next to his contemporary Emmanuel Guibert (which should tell you how highly I think of Guibert).

I’m unclear how much of this book is strict biography and how much is fiction, but I also know that may not be the point. Pascin’s paintings seem to have conveyed a certain narrative of life on the seedy side, and Sfar’s graphic novel embraces the same, at least as a fascination if not a manifesto. Its focus on charming depravity channeled into artistic beauty, unfolding in a series of short episodes, reminds me of Sfar’s Serge Gainsbourg biopic more than anything else he has done, but far more successful. Whereas Gainsbourg was too reverent of its subject and a little pedantic in its greatest hits biography style, Pascin is treated as more of a complicated character with a real dark and light aspects, in a story that unfolds in a casual way, at least insofar as its historical accuracy. It’s much more concerned with the emotional and philosophical content of what it presents than spelling out circumstances in any clear way that biographers typically employ.

If the philosophical and intellectual points of the graphic novel can engaging and offer substance to grab onto, the personal notes in it are much harder. Pascin isn’t portrayed as a particularly likeable guy and is actually a bit tiresome, so your interest depends on your tolerance of him. If self-destructive, self-important, mopey guys are people you don’t mind dealing with, then you will probably find yourself fascinated by Pascin.

Because it’s the work of Sfar, you can be sure that it’s beautifully rendered and realized, with his scratchy, dishevelled style perfectly matching the scratchy, dishevelled world that he documents, accentuated by his sly humor. It’s an immersive project in this way and the center of the book’s success, but I have to admit that it’s hard to connect with the book if your emotion toward Pascin is defined by distance and the feeling that he’s that guy you always run into that you will cross the street to avoid. However, if you’re not like me, this is probably the book for you, because there are few finer graphic novelists in the world that Sfar and even if I don’t quite connect with this one, the level of his artistry still stands out in Pascin.