If you had asked me a week ago what I thought of the idea of a comic about the ghost of Sid Vicious palling around with a modern-day kid, I’m not sure what my answer would have been. It might have been an eye-roll. The idea in itself seems rich for lame punk nostalgia and gross, inappropriate heart-felt gooshiness. Or maybe the exact opposite. Someone could use concoct the scenario for over-the-top rudeness, using the Vicious character as an excuse to portray questionable behavior in some sort of sad bid to go after political correctness.

But that’s if you had asked me a week ago.

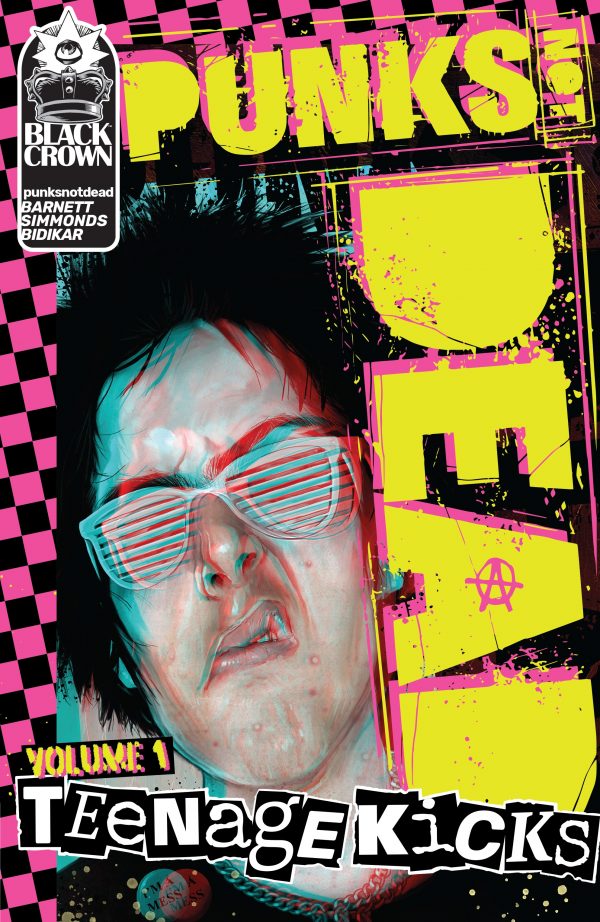

That premise I laid out there is exactly what Punk’s Not Dead Volume 1: Teenage Kicks is about, at least in its most basic terms. Written by David Barnett with art by Martin Simmonds, the modern day kid is Fergie, obviously named in tribute to Feargal Sharkey, and after a strange event in Heathrow Airport shackled to the ghost of Sid Vicious. Sid has been haunting the place ever since his mother accidentally left a bit of him there, and here he comes off as a bit of a trickster, though with not enough foresight to actually disrupt much. A little dopey, a little sweet, a bit impulsive and inarguably thick, Sid is about as agreeable as a ghost sidekick could be, actually.

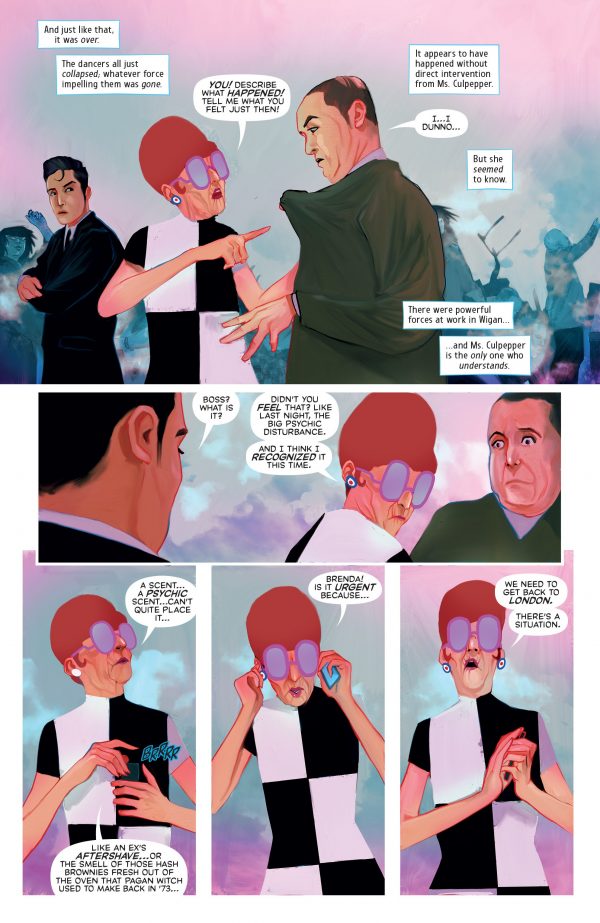

But Sid leaving Heathrow triggers some high-level supernatural alarms that have forces like the Department of Extra-Usual Affairs, a government agency devoted to monitoring paranormal events, investigating other music-related disruptions, including a never-ending rave of old people at the site of a former Northern Soul music event.

Heading up the department is Dorothy Culpepper, an old lady in groovy Emma Peel outfits. Actually, she has a story of her own, but I won’t reveal that here. Suffice it to say, she’s her own supernatural phenomenon and she’s been tracing Vicious for a while. His sudden departure from Heathrow and the ensuing supernatural alarm bells has her looking into Fergie closer, especially after his tussle with a fellow student that resulted in a mysterious impact that no one can explain, least of all the guy who was impacted.

There’s a level to which this all appears so chaotic, but that’s a ruse, much like the Sex Pistol’s music and career itself. And if so much has been added to the ultimate goal underlying punk of the 1970s, it should be noted that most of those folks stuck around long after punk had become deceased or transformed into an American phenomenon or whatever, and turned their attention to pop-oriented music, whether they were hits or not. Punk was only briefly against the grain, only briefly political, at least in its English form, and Vicious’ legend benefits from his young death before the music’s demise.

That’s actually important to Punk Isn’t Dead, because what the ghost of Vicious is used for isn’t to re-radicalize the movement, to give it back its significance. Quite the opposite. Vicious is there to humanize it. The Sex Pistols weren’t four revolutionaries out to change everything — well, five if you count Malcolm McLaren, and I do. They were four kids and a Fagin having an adventure, making some money, scoring some clothes and whatever else they desired. They were human and swept up by the times, and that’s the Sid Vicious who appears in Punk’s Not Dead.

Barnett has a knack for letting the history of British pop music seep its way into the crevices of the adventure, and Simmonds is great at pulling in the needed visual styles to express this light scholarship, but it’s important for the book to not become a bunch of references thrown into a plot in lieu of something to actually involve the reader. Instead, it joins together seamlessly and naturally, another way in which punk is not seen as something that happened in a vacuum, but part of a continuum. There is a straight link from Dorothy Culpepper to Sid Vicious, and even beyond, actually, and that’s wherein the beauty of Punk’s Not Dead lies within the good fun it tosses out.

This was a great book. I’m waiting for the second series.

Comments are closed.