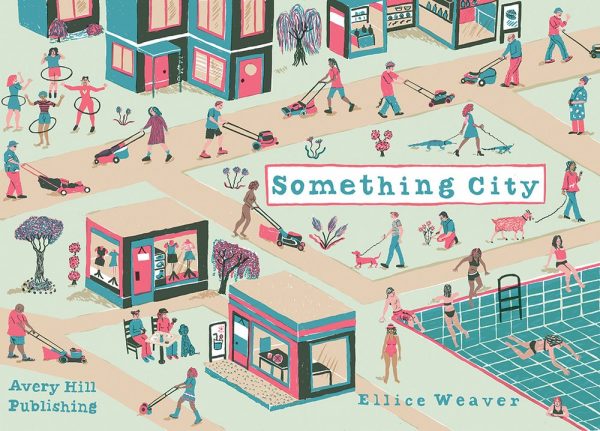

Like a Richard Scarry book for the modern urbanite, Ellice Weaver’s beautifully drawn Something City weaves together various corners of an urban environment to create a tapestry of experience that portrays the trees to make the forest more clear. A city is a super-organism, a compilation of sections and neighborhoods, which are in turn the sum of their residents.

Each short piece in Something City corresponds to an area of the city, with some characters and situations making more than one appearance, but none dominating the travelogue. These are pit stops that give you a flavor for the parts of the city, echoing the intro to the old TV show Naked City that promises you the existence of eight million stories there. In Something City, there are at least 10, but probably more.

In “Upperhaven Squaresville,” a couple has moved to the city to start a new life after some unknown tragedy that resulted in the harassment of the woman. We move along with them in their new life, as the mundanity of it seems to pierce the woman, and the incident that brought them to the city is revealed.

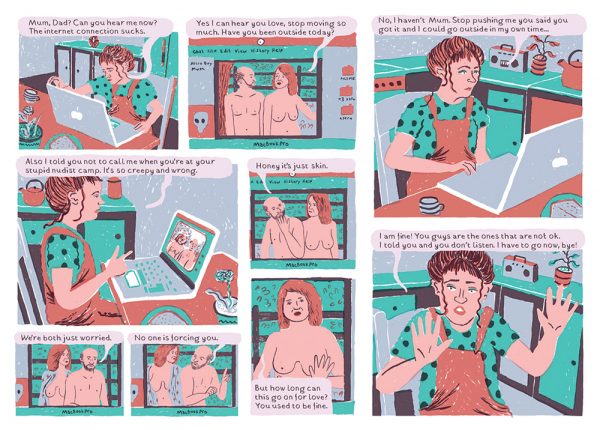

“Free Body Culture Club” takes place at a nudist retreat focused on self-actualization where our main character, Dr. Jenn, doesn’t want to be self-actualized, doesn’t want to be nude, and doesn’t want to admit that there is anything so bad in her life that she wants to meditate it away. This is probably my favorite in the book, and the idea that there are many roads to peace and/or zen — even rocky ones that some people don’t accept as spiritual roads — jibes with my life experience.

In “Ashford Minimum Security Prison” a method concocted to separate a prisoner from the others, and to stay out of trouble, may end up working the opposite. This is both a good thing and a bad thing, and these add up to some sweet and awkward comedic moments.

The free spirit vibe of the nudist colony is contrasted with “Brook Field Terrace,” in which the daughter of nudists delivers a soliloquy on why she won’t go outside. It’s a burden she feels not because of just fears for herself, but fears for everyone, and it’s measured against the hugeness of the university and the personal responsibility she feels for protecting the tiny — that is, us.

“Old Networth Square” concerns itself with the new town square, the virtual one on social networks, and the idea that presentation of self is a meticulously curated one. You are not who you actually are, but who you want to be, when operating on Face Action, and who you want to be is contingent on physical appearance. It’s the opposite of the promise of the internet, but perhaps those engineers never foresaw selfies.

In “Downtown Urban Spree” a girls’ night out prompts drunken discussion and relationship empowerment, but it’s quick to notice that no matter what your plans are for self-improvement, the other person might have their own, too — especially when your hesitation to be decisive may play into their checkmate.

“Everton Rest Village” offers a look at the way we approach endings, specifically our own, and the idea that it’s the people who aren’t reaching that finality who have the toughest time with it. That becomes obvious in the tour of the retirement home, where the elderly are sent to wile away their last moments in life, waiting and diverted.

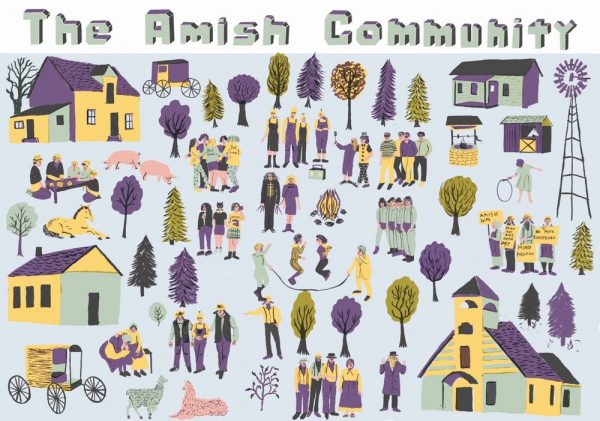

It turns out there are Amish living in Something City and “The Amish Community” offers a situation where Pokemon cards become a mysterious missive from the outside world, and are used to plant a seed of questioning in an Amish girl whose sister has left for the outside world.

“Fisher’s Floating Pontoon” visits the local fish market and introduces us to Matt, who make plenty of claims about fantastic things he’s done in his life, like appear on Oprah’s TV show. His co-workers question these tales, no surprise, but as we accompany Matt into his private life we are shown that interpretation of events is a definitely part of how you experience reality.

“Hound Town Avenue” features Dr. Jenn from the nudist retreat, taking a look at her medical practice, but really circles back to “Upperhaven Squaresville,” where we meet a woman mentioned in that story and find out how she is coping. It’s a bittersweet farewell to the city and the most direct examination of how two different realities can exist in one defined space.

Weaver intersperses these brief slices of life with panels and splashes capturing various moments around the city, as well as a couple media divergences and, in the end, a map of how each character is related to others.

It’s much like moving into a real neighborhood, actually. You meet this person, you meet that person, you hear stories, you decipher cryptic comments, you take note of the movement of people you don’t know, you put the pieces together and try to come up with what you think is going on. In Weaver’s hands, that common exercise is imbued with extra mystery and whimsy, but never so much that there isn’t an emotional truth at the center of the characters’ dramas, adding up to a fully realized example of world building in its purest form.

Comments are closed.