As I’m probably too fond of saying, each year’s San Diego Comic-Con represents the end of comics’ fiscal year, and we’re now in a new cycle of sales, renewal and looking forward to the next thing. Although the con was not that memorable on its own, it did mark a new plateau in the direct sales era for comics penetration into the mass media, and for having a variety of voices and genres that the medium has probably has never been seen before.

This situation, while far from ideal, still represents a dream come true for a lot of us who have been toiling in the comics industry for a while. I remember as if it were yesterday, sitting in various comics industry think tanks in the 90s wondering WHAT could be done to expand the audience for comics, how to bring in genres that weren’t superheroes, and how to overcome the tyranny of the “32 page pamphlet” as it was dubbed by either Kurt Busiek or Marv Wolfman, depending on who you ask. These tasks seemed daunting at the time, and it actually took 25 years to get to a place where it could be argued that it’s true, and everyone at those meetings is a certified old timer now.

Chris Butcher is too young to have been at Pro/Con in 1992, but he’s shared some of the same goals and aspirations as manager of The Beguiling. And at Comic-Con 2015, Chris Butcher looked around and saw that it was good as he recounts in an essay called Shifts and living history, which traces this road to a diverse industry back to the manga revolution of the turn of the century, a revolution that wasn’t always welcome:

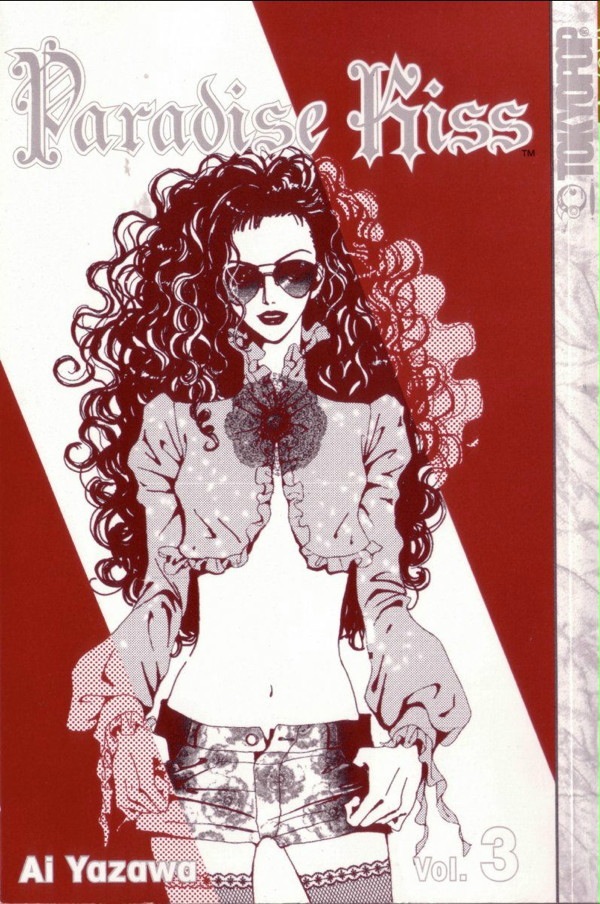

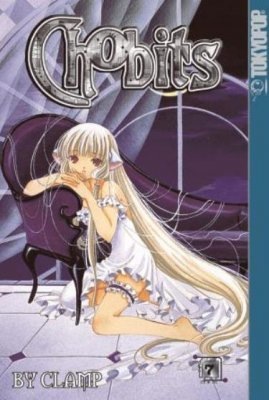

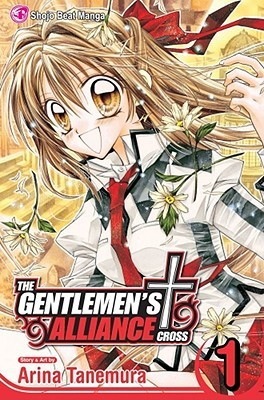

So, basically, my theory goes that the manga boom in the late 90s sort of blew up every single thing that the industry thought about comics, and who the audience is for comics, and what comics can do. I’ve been writing about comics on and off since about 96-97, and I’ve been writing not only about the potential for comics, but then the realization of comics. It was a time of really quick change, a lot of it good change, sparked mostly by $10 trade paperbacks of Sailor Moon (big-ups to Tokyopop). The success of those books and the ones that followed like Card Captor Sakura, Peach Girl, Fruits Basket, and so many more, were the proof to the theories that comics could be for everyone, for women and for girls especially, and could sell in numbers that were comparable to how they sold overseas. Then Viz launched Shonen Jump, Random House launched the Del Rey Manga line (now Kodansha), Hachette launched Yen Press. The comics came out, the comics sold well, the comics brought in new audiences. Sales exploded, sales leveled, sales crashed, sales leveled again, and just this year everyone’s saying that sales are up a little once more. Not just for girls and women, but across the board. This is all stuff that actually happened, and you can go back and look it up if you don’t want to take my word for it.

As I read this, I thought to myself, a victory lap for manga! Triumphalism! Awright! It was surely the influx of new readers to Borders and (to a lesser extent) B&N that solidified the graphic novel sections to the largeish rack we now have. But Butcher also points out something that I also noted at the time: some people who were majorly invested in the old ways did not want to admit that manga and the kids market that emerged around the same time were actually proper comics and “othered” them to use Butcher’s chosen term. Manga, in particular, was scoffed at and doubted and questioned. I can’t tell you how many articles I wrote for Publishers Weekly during this time that asked “When will the manga fad end?” and I could tell many people hoped it was soon. Not because they were bad people or hated comics, but just because manga wasn’t their thing and, sure, maybe dozens of teenaged girls dressed as maids made them uncomfortable. But despite this squeamishness, a new industry emerged, Butcher writes:

So, the comics industry was able to successfully ignore the massive success and new audiences that the manga publishers brought with them. But you know who didn’t? Kids publishers. Scholastic Graphix. Papercutz. Abrams. First Second. Kids Can Press. Even Yen Press’ arm at Hachette. They saw that with the right conditions, you could get someone other than males aged 18-49 to read comics, and have it be incredibly successful. These publishers paid attention and put together imprints to publish original work specifically for the audiences that the comics mainstream insisted didn’t exist: Kids, girls especially, tweens and teens. And the books sold well. Won new audiences. A whole industry of “original graphic-novel” based creation sprung up that simply did not exist before the success of manga, the success of Bone at Graphix, of Twlight: The Manga at Hachette, Nancy Drew & Hardy Boys graphic novels, Binky the Space Cat, Diary of a Wimpy Kid, American Born Chinese. Or Smile, by Raina Telgemeier. Smile, which sat on the bestseller list for a year and was largely disregarded by the comics industry. Incredible bestsellers, many with outside-of-comics media attention, largely ignored, deliberately ignored. Because their success didn’t fit the paradigm. They weren’t comics. They were ‘for kids’.

Butcher’s narrative pretty much backs up my own experiences during the period, although a more charitable interpretation could be that comics are a big enough house to have separate rooms for a lot of different readers. Just because you like Harley Quinn doesn’t mean you’re going to like Black Butler, and vice versa.

I was a little surprised when Tom Spurgeon took exception with Butcher’s essay, even dubbing it “manga triumphalism” in a disparaging way.

Claiming the success of Raina Telgemeier as manga’s, even in oblique fashion, feels to me like a last cry for manga triumphalism. That was a way of looking at comics in the ’90s into the ’00s that insisted manga was going to be the absolute dominant and defining market force in the US for decades to come, imagined a lot of enemies where they didn’t really exist and made suggestions like complete and radical format change for North American publishers or the withdrawal of all money from direct market store support. It seems to me there was a lot of “othering” manga from pro-manga advocates, too, and while imagining it was subconscious resistance to female audiences that kept people from a full and mighty embrace is appealing rhetoric, that’s a really specific construction to connect so many people with vastly different backgrounds and approaches to the medium.

While both these arguments are dredging up old pre social media online squabbling, and it’s undoubtedly true that some manga proponents were a bit obnoxious in their glee over manga—which read backwards and often didn’t make sense and came in endless volumes about people who sneezed—completely thumping Occidental comics in the Bookscan numbers for years and years. In fact, you can look at ICv2’s Bookscan listings since 2008 and see that it wasn’t until the post New 52/Walking Dead era that Western comics began to dominate the top 20. You can just look at the headlines on that page and it’s crystal clear when the shift happened. Walking Dead began airing in 2010 and between that and the influx of new readers from DC’s massive advertising push for The New 52 in late 2011, a huge paradigm shift occurred in the comics marketplace that we’re still seeing the results of. And while there were new readers of all kinds, the majority of the new readers were female.

Now, perhaps you can’t draw an exact line between the girls at Otakon in 2006 and the women reading lady Thor now. There were many factors, including social media and Marvel’s cinematic universe, that made women purchase more comics, and, conversely, made purchasing comics more acceptable for young women.

But what I would say is UNDENIABLE is that the massive influx of female creators who are being taken seriously in comics now, and having extensive sales success, was largely influenced by manga. Not wholly, but largely. Again, I can’t say if its 40% or 80%…but a lot of female creators I talk to now read manga as teens. They may not have been cosplayers, but they had a manga series or two—or ten—that they read. In an interview from a few years ago, Raina Telgemeier actually

addresses this:

Your work combines both comic and manga styles. And for younger readers, comics and manga seem interchangeable. Do you think that is the future of the industry in general, a melding of these two seemingly different worlds?

I read manga and comic strips when I was growing up, and they both worked their way into my artistic sensibility, although I’m by no means a manga artist. Most of the young cartoonists I encounter these days seem to be heavily influenced by manga and anime, but I think that’s because it’s so readily available to read and watch. I don’t know. The world keeps evolving, and comics will keep evolving with it. Any time a really popular animated TV show spawns a fandom, the style of that show will start to creep into peoples’ art styles, too—right now I’m seeing lots of comics that are obviously inspired by Adventure Time, My Little Pony: Friendship Is Magic, and Avatar: The Last Airbender!

The influence of manga on today’s comics sales boom (modest though that boom may be in historical terms) is still being assessed, but I think the industry owes a lot to TokyoPop’s Stuart Levy (for all his faults), Viz’s Dallas Middaugh, Kurt Hassler at Borders and the other architects of the manga era (All now moved to other companies.). And while manga sales may have slumped from their peak, they still have some punch, as Attack on Titan’s 2.5 million copies in print show.

[Photo by Gina Gagliano)

Several people besides Chris Butcher have taken this moment to take a deep breath and get comfortable in their easy chair just to survey where we’re at. First Second’s Gina Gagliano wrote about this year’s historic Eisner Awards in terms of how it showed a broadened industry and quoted many folk, such as librarian Robin Brenner.

“This year is showing a change in both the library and the comics industry,” says Robin Brenner, Teen Librarian in Brookline, editor-in-chief of No Flying No Tights, and former Eisner Awards judge. “When graphic novels were recognized earlier this year by the ALA with both Newbery honors and a Printz honor, there was a palpable sense of graphic novels moving forward another step in terms of being recognized as the remarkable, literary achievements they can be. However, given the gulf that has existed between the book publishing world and the comics publishing world, in terms of the awareness and recognition of different creators and works, I admit I was surprised and delighted to see the Eisners highlight many of the same creators and achievements. As an industry award, the Eisners reflect their voters, and the industry in the past has kept pretty close to the names and publishers they know within traditional comics. In the past this has shown a lack of awareness of the comics and graphic novels being produced outside of the traditional comics publishing world. This year, though, there was crossover, and with people like Jillian and Mariko Tamaki, Cece Bell, Raina Telgemeier, Emily Carroll, the Lumberjanes crew, and Gene Yang all recognized, the winners emphasized that whatever divides between those two publishing spheres is happily breaking down. As a librarian and a reader who’s always simply looked for the best comics from all origin points, it’s wonderful to see such barriers fading away.”

And Sktchd’s David Harper, who is slowly working his way through all the major industry debate topics, sort of recreates two decade’s worth of thinking about pamphlets vs books in a think piece called Do Publishers Need to Rethink the Format of Comics?

It’s not just outdistancing floppies in revenue, though. The graphic novel market is growing, and at an even faster rate than floppies. In the numbers Miller shared, floppies surpassed the growth of graphic novels over the past three years. But much of the growth came in 2012 thanks to surges driven by the New 52, Marvel NOW! and the ascent of books like The Walking Dead and Saga. If you focus on the past two years, though, graphic novels have outgrown floppies by just over 6 percent. Miller explained why: “The acceleration in graphic novel sales growth has mostly come from the book channel, though graphic novel growth slightly outpaced comics growth in 2014 in the comic shops as well,” he said. “Part of what is going on has to (do) with the inclusion of a lot of titles that for various reasons are not captured by Diamond’s reports; comics retailers ordering directly from Scholastic, for example, would see their sales included under Book Channel.”

The reality is that having a diverse group of channels—digital, periodical, graphic novel, web, mobile and inside DVD boxes—is healthy and keeping them all around as long as they work is a great idea. We need every sale.

And while gloating triumphalism is obnoxious, speaking personally, I’m only human. Those of us who believed we could build a more diverse and successful comics industry that appealed to a wider range of readers were right all along. Woo hoo!

FINALLY, if you got all the way to the end of this, just to put an end cap on this book display, Milton Griepp checked out his local Barnes and Noble and checks out the newly expanded GN sections:

The space increase is massive. In June, the Barnes & Noble in Madison, Wisconsin, a store on the larger end of the chain’s 648 stores nationwide, had 10 graphic novel bays, including five manga bays, two for DC, two for everything else, and one for Marvel. That was up from the low for the section, but apparently just the beginning.

When we visited the store again this week, there were 18, count ‘em, 18 graphic novel bays. They were still divided 50/50 between manga and everything else, but the displays had been dramatically reorganized.

The new display includes a handsome end cap, replete with a diverse mix of styles and genres. I think we all won here. Now, on to the the next battle.

(Photo by Milton Griepp)

Speaking as someone who was in the thick of the expansion of graphic novels into the book and library channels and as the co-founder of Yen Press I want to point out a few things. Western style graphic novels and manga owe a great deal to each other; manga would not have been introduced into bookstores if efforts by American comic book publishers to get their books into these outlets hadn’t happened. In the late 1990s it was difficult to get any graphic novel into these outlets. Once that wall began to come down, retailers were more responsive to try out manga titles. The reason that manga dominated BookScan was that the bookstore market was; that’s where the core fans shopped. The direct market retailer, for the most part, did not represent manga the way bookstore chains did. So the fans flocked to bookstores and libraries.

On the flip side, the comic shops were where the core fans of DC, Marvel, Dark Horse, etc. all shopped. For manga BookScan was more of a comprehensive look at the retail piece of that business (libraries are not accounted for on BookScan). The BookScan numbers for American graphic novels represented an expansion of new readers beyond the core fan. While at DC I wanted to build a way to have the direct market retailers report into BookScan. In my eyes they were the trade book industry’s version of the independent bookseller. I would suggest that now the core customer for trade books of American titles is split between direct and book retailers.

As for the lasting effect of the manga audience, of course there are current writers and artists who grew up reading manga. It’s only natural they would be influenced by it. The same goes for American comics. We are looking at a time where anyone who is fifteen years old has lived in world where both manga and American graphic novels were available in bookstores and libraries. And we are now entering an era where the same will be said for digital comics. Expanding the reach of the medium will naturally increase the readership and influence generations of artists and writers. We are luck to live at time where the medium, regardless of country of origin, or art styles have as many outlets for potential readers. That is truly triumphant.

The summary: Manga blazed the trail into bookstores. The Book Trade notices the sales, and begins to produce original imprints as well as distributing comics publishers. The Internet facilitates discussion among librarians, critics, and fans.

—

In 1994, when I started as a bookseller, the following comics publishers were available to the bookstore/library market:

Marvel

DC

Viz

Dark Horse

First (the remnants)

WaRP

Cartoon Books

Curiously, even though comic strip collections were on the New York Times bestseller list, I rarely saw comic strip collections (the most mainstream comics of the day!) in comics shops.

In 1999, the market expanded, as Spawn had a Random House reissue (all other Image titles unavailable), and Fantagraphics began distribution with … Norton? (Or was it someone else?) That year, Viz, in bookstores for a decade, introduced Pokemon.

It was Pokemon, with the multi-platform marketing, which launched manga, not Sailor Moon.

Sailor Moon pissed off the fans with censored Saturday Morning cartoons, and Mixx (later Tokyopop) had no bookstore distribution, so all I could order for my store was the Meet Sailor Moon guidebook from Random House.

Manga succeeds because it’s already been tested in Japan. Import the titles which are popular with kids and teens.

Manga had a foothold in comics shops via Eclipse, Viz, and Dark Horse. Via comicbooks, not graphic novels.

Bookstores had been computerized ever since Borders in the 70s. Libraries barcoded books in the early 1990s. Both were able to track inventories and notice when manga and graphic novels began to sell/circulate. Compare to comics shops (where many stores still don’t have an e-commerce site, and some don’t have computerized sales systems.)

Once the books begin to sell, then whomever reads the Bookscan data can notice the trend. That’s why, in 2002, you began to see mainstream publishers slowly enter the bookstore market with comics, mostly with the help of comics moles/the geek diaspora. Also, LPC and CDS began to distribute many comics publishers (CrossGen, Tokyopop, Humanoids) to the trade in 2000.

There’s another factor that comes into play here regarding the growth of the gn category in the traditional market, as the buyer in the libraries paid greater attention to the circulation numbers for GN titles like Bone, Blankets, Maus and Persepolis they began looking for more content and the librarians were very vocal with the publishing industry about what the audience/patrons wanted and libraries needed:MORE Graphic Novels PLEASE. So when Smile was successful it encouraged other houses to follow suit. Wimpy Kid filled and still fills an incredible demand as a graphic novel in the educational market. Because of Smile you have so many more great books to follow. As the category began to strengthen independent bookstore owners grew their selections. During this time the Eisner Awards also began to gain credibility as a legitimate award in the library market which also has a librarian as a judge.

The next market? K-12. You have two generations of educators and school librarians who grew up with manga and western-style comics/graphic novels. They do an awesome job of articulating the value of comics as a literary device or tool for the classroom. The really cool thing is-they now have a really nice global catalog of graphic novels to use in their classrooms and media resource centers aka libraries. As these ‘new kids’ become the decision makers comics will hit another high point spawning even more talented creators and fantastic books.

What an awesome time to be in this business!

One critical element in all of this? Comics publishers need to learn how to operate as business people and use the same tools that Scholastic, Capstone, First Second, etc for getting books into the book trade. NONE of the buyers in the book trade know or care anything about the way the direct market operates. If you, mister publisher can master the book trade language, you have a chance to do very well.

I’ll right away snatch your rss as I can’t in finding

your e-mail subscription link or newsletter service.

Do you’ve any? Please let me know so that I could

subscribe. Thanks.

The primary cheats or hints that we are going to tell you is for any kind of device.

Kun opiskelet pokeria elävällä kouluttaja , hän voi pahenevat

jos et yksinkertaisesti eivät saa sitä .

La plancha gaz chauffe aussi plus rapidement ainsi d’attendre

longtemps pour organizations to a vos premieres.

It’s really very complicated in this full of activity life to listen news on TV, thus I only use web for that reason, and get the hottest

information.

Ce cuiseur m’a permis de faire toute les purees et compotes de mon fils pendant 10 mois!!

Comments are closed.