As America lurches forward to this week’s inauguration of one Donald J. Trump to be the Forty-Fifth President, the country finds itself at a crossroads. For some, the ascension of Trump is a repudiation of the so-called “mainstream,” a fresh start. But for the majority of voters, this wasn’t supposed to happen. How could a personified meme triumph over someone who had spent years in public service and had all the experience in the world to take over the job of commander-in-chief? In the purgatory between the last days of Obama and the age of Trump, there’s been agitation on both sides of how to react. Even then, there are degrees of what emotions to feel: exasperation, perhaps? maybe resignation? Or… how about resistance?!

For the editors and publisher of RESIST!, a sprawling collection of grassroots cartoons and comix from artists all over the world, this latter emotion was (obviously) the only way to respond. RESIST! is the brainchild of Gabe Fowler who, as the owner of Desert Island Books in Brooklyn, is also the publisher of Smoke Signal, an independent quarterly anthology of comics, in collaboration with Françoise Mouly and Nadja Spiegelman. From the moment the first open call was announced in late November, thousands of artists submitted pieces to the magazine. Now, after weeks of hard work, planning, editing, and cultivating, the final product is ready to launch just in time for this Friday’s inauguration festivities. The COMICS BEAT sat down with Fowler, Spiegelman, and Mouly to discuss the genesis and logistics of the RESIST! project, the meaning of political art, and what’s next for cartoonists in the era of President Trump.

AJ FROST: What were your first thoughts that November night when Donald Trump was elected as President of the United States? And how did you feel about it?

GABE FOLWER: Grim.

NADJA SPIEGELMAN: I was in Paris, so I stayed up as late as I could but went to bed at 2 or 3 in the morning. When I went to bed, it looked like Florida was going to be won by Hillary and things were going to be okay. So I went to bed hopeful. But then I woke up at 6 AM with my phone going off and saw text messages that just said ‘No! No! No!’ I really felt like I was waking up into a nightmare, or a parallel universe. I kept hoping that if I went back to sleep, I could somehow wake up to a world where this wasn’t the case. I ended up going to a café. Now, cafés in Paris are places where most people go to get their morning coffee and discuss the news, especially when some big event happens; it’s a place where people can congregate. I wanted that sense of community and, yet, I felt alienated because, for the Parisians reacting to this news, it was horrifying for some, amusing for some, but it wasn’t as visceral as it felt for me.

When I began speaking to my friends back in America, I also felt alienated because they were seeing it as an American problem, when for me it seemed so connected to this global movement towards the extreme right; whatever happens in America has a global affect. That was part of why, when my Mom and I began trying to figure out what specifically our call was, I wanted to not just resist Trump, but to resist it all: resist fascism, resist everything worldwide that is happening!

FRANÇOISE MOULY: For me, it had to do with seeing the very specifics because I work in media. I had to make plans for what I thought would be the result of the election.

And I had told artists that I work with at the New Yorker to keep sending me schedules, keep sending me ideas because after the election we can rest, because, of course, we were going to be celebrating the first woman president. And then, the narratives that had been so breathless for a year could take a break because we were in a world that we had been planning for. It didn’t occur to me in the middle of the night between [November] 8th and 9th when I realized that that scenario was so off the mark. I wasn’t ready for that. It wasn’t like there was ‘Plan A’ and ‘Plan B.’ But I was at the receiving end of David Remnick [editor-in-chief of the New Yorker] putting out a strong denunciation of Trump on our website and then gathering the staff and saying ‘We have a job to do.’ I was very grateful to be in an environment, with colleagues around me, that were in a shared situation.

I couldn’t imagine what it would be like—not so much for people in New York because everyone in New York was in catatonia-land—in Arizona or somewhere where you’d go to work and half the people would be celebrating. We didn’t even need to have conversations; we all knew we shared the sense of a shattered reality. I wanted to, in a way, use what I had, which was: ‘I’m not doing anything. I’m going back to bed and pulling the covers over my head and not answering the phone or my emails. I never again wanted to check out the news. I didn’t want hear any words.’ But then, when I was told, like: ‘Ok! We’re doing something. We’re putting an issue out. Our job is more important than ever!’ I realized that as violently as I was thrust into this, it had a salutary effect. It’s better, even when you think you can’t, you can. It’s better to do something…

I started going through the stages of denial, then anger—whatever it was—and then back to anger. I never got to the part where you settle. I kept doing it like a wheel: any steps I tried to process would get me back to the anger part.

FOWLER: We need leaders with detailed knowledge of the intricacies of world leadership, not self-interested aristocrats who would happily rape the earth for a quick buck.

MOULY: Moving forward and making something, I had to come up with a cover for the [New Yorker] issue that was going to press within a couple of days [after the election], and the week after and make plans; I couldn’t mentally stay in that place of non-action. When I got the call from Gabe offering to do something for a specific date, then that felt that it was way more than I could take on. But, on the other hand, it is a deadline. And deadlines are useful.

In all my professional life, forty years in comics, I realized printing something—an artifact—is something I understand. It’s a way for me to remember my past. I can remember when my children were born… I can remember which book I printed/published when. I have a way of mapping out my history through publication. And that felt right to have such a publication as my way out of some insurmountable moment. For me in a way, it was a little bit of a replay of September 11th when I couldn’t figure what to do and I eventually came up with this New Yorker cover of black-on-black from [Art Spiegelman’s] suggestion that this was a way to show that there was no solution. Similarly, Gabe’s offer felt like this would be a printed artifact that will catalyze and focus a complex and inarticulate response.

FROST: Gabe, when did the idea pop in your head that you should devote an entire issue of SMOKE SIGNAL to political comix, especially by female artists?

FOWLER: I was immediately disgusted by the election results and was grasping for any positive course of action. Since I already publish a comics newspaper [Smoke Signal], the first and best thought was an issue devoted to artists’ responses to this fresh hell. My friend suggested an all-woman issue, which immediately felt right, and made want to get out of the way as editor. The very first person I envisioned as guest editor was Françoise Mouly, an absolute genius and one of the most important women in the history of comics. When she agreed, along with co-editor Nadja Spiegelman, the project took off like a rocket and hasn’t slowed down since!

FROST: And Nadja & Françoise, what your first reaction to Gabe’s offer was to take over and re-brand Smoke Signal? Did it feel like more of an opportunity or more of a burden?

MOULY: Both, but there were a few factors at play. The first thing I said to [Gabe] was ‘Give me some time!’ But there were a few things that were important: One is that I know Gabe and I trust him. He’s a straight shooter: When he said ‘no strings attached,’ he meant ‘no strings attached.’ There are very few people who have ever offered me an opportunity that is truly no strings attached and this one he was taking very seriously. I didn’t have any doubts about this.

The other was… the timing was such that, when Gabe offered it to me, I was on my way to California for something that I had scheduled that would take place after the election. I thought it would be a triumphant recall of all the New Yorker covers leading up to the election, so I had prepared it in a certain way. And then all of the sudden I was bereft. Instead, I ended up giving a lecture about political art; I ended up giving a recap of my life with printing presses, going back to doing mail books, even before I did Raw. I couldn’t understand because it was the most inefficient way to expound [my feelings]. But then I realized, No! I need to reconnect to what I believe in, to what I understand.

FOLWER: Françoise responded the same day and said ‘We have to do something, and this is the project for which I would drop everything. Let me sleep on it.’ I think she wanted Nadja to talk her out of it, but instead they both came onboard a few days later.

MOULY: I did a presentation that was supposed to be 50 minutes and ending up being an hour and 50 minutes. I moved through mail books, to Raw, to Little Lit, to Toon Books, to New Yorker covers in the present moment, via going back to Charlie Hebdo, and Fred, and publishing Philemon. To the rational part of my mind, it sounded completely like, ‘What is this about?’ And to the irrational part of mind, it was like, ‘Well, that’s me!’ It was the common denominator of the things I believe in. After I delivered [the lecture], I called Gabe and said I’d do it. I just realized that I basically defined myself as the printed publications I can make.

I had this interesting exchange where I called my mom and said, ‘Oh I have this offer to do something against Trump…’ [And she said,] ‘Are you crazy? You’re always talking about how you have too much to do. And you gotta say no. And you’re not going to take on one more thing. Why are you even considering it?…’ And then I told my son, and I said I got this offer to do this, could you play Devil’s advocate and tell me why I shouldn’t do it? And he said, ‘No, of course you have to do this. This is exactly what say you believe in.’ It was clear at that point that Gabe’s call wasn’t out of the blue. It really came from some understanding of what I could do.

And the other thing was that it was right before Thanksgiving that I was doing all this, and I knew that Nadja was coming. We had done things together and what was really interesting to me was this blank check that Gabe was giving me. It was not so much reaching out to the artists I knew, because of course I did send the call to everyone women artist that I know. I could I could actually create an open call and do something that would be far wider; I find open calls really exciting because you’re exposed to things that you don’t know, which by definition you can’t be when you’re the one making all the calls. You have, as an art director or as an editor, a vision of what your aiming for and you need artists to help shape that vision. But here, especially once Nadja just jumped into the fray, I felt we not just working as mother and daughter, but also multi-generationally. She understands that kind of democratic discourse better than I do. We worked very well together, and I think together we gave RESIST! the range that it need to have because it is both a look at the past and a look into the future.

SPIEGELMAN: RESIST! is both ephemeral and permanent, by both being on the web and being a printed publication, and openly democratic to everybody. Because of the open call, we also expanded the mode of distribution from one hand to another. I just want to say that I love working with my mom. It’s so awe-inspiring to watch her edit because she’s an expert and has been doing for years; and she’s brilliant! To be able to watch the speed by which she can go through images and see which ones work together, understand them, know how to correspond with artists… I learned so much from working from her.

FROST: What did it mean to all of you that once you sent out the open call and it started making made the rounds online, that thousands of people submitted art to RESIST? To me, it seemed to have a real positive impact…

MOULY: That what was so exhilarating. We became midwives to RESIST! as opposed to being the omniscient creators. It felt like it was actually articulating something that hadn’t been done before. I’d just been, in the months leading up to the open call, at the receiving end (because of my role at the New Yorker) of women lobbying for more of a women’s voice [in media]. And, they went at it the old-fashioned way, which is you shame people and come at them and ask ‘How many women, Muslims, black women, and so on, do you have on your staff?’ Which is not much motivation compared what we put in place here, which was a skeleton and a structure. We intuited from our own experience that there was a voice out there, and that it just needed an envelope in which to fill it. We didn’t go and take this piece and that piece and then make something which we had designed. We actually just facilitated a manifestation of something that we didn’t know what to do with. We didn’t commission or create the content of what was said.

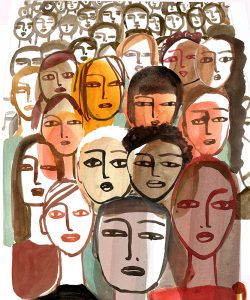

SPIEGELMAN: Once women understood that they were speaking as a collective voice and they could speak for themselves, the fact that they were women was taken for granted. Getting that range, that harmony, that collective voice all speaking at once condensed into RESIST! was so exciting.

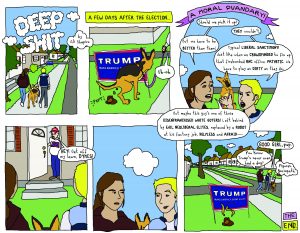

MOULY: There’s a number of phenomena that happened in an organic way, like a slow-motion video of a plant growing or a multi-celled organism organizing itself into colonies. It was fascinating. It’s not an experiment that any editor has been allowed to conduct, to say ‘Tell me if you’re a man or a woman, or a different [or no] gender…’ Who says that? So we separated the mission into men and women and saw trends over time. At the beginning, we saw a lot of established artists sending us anti-Trump images that they had already done; we showed a few of these on the site. We were also showing things in real time; Nadja was updating the website every day. Then, we started showing more women’s voices and I said specifically we would like more comics, and then we started getting more comics by women.

As more and more examples were shown [online], then each person felt, in a congenial environment, free to talk about her. Not standing in for all women, but by her specific experience. That became really exciting. Including people who are not artists, like thirteen-year-old kids, and academics, and people who’ve never really drawn but were sketching things out… We were creating a kind of bathhouse space where women could be comfortable with one another…

FOWLER: This project is about inclusivity and a roar of voices being heard. In her role as art editor for the New Yorker, every illustrator on earth wants Françoise to see their work. Her editorial power drew immediate attention from international artists, and Nadja created an effective website as a submission portal and project documentation. Both Nadja and Françoise constantly brought fresh ideas to the table and did not shy away from the more tedious logistics of shipping and nationally organizing volunteers.

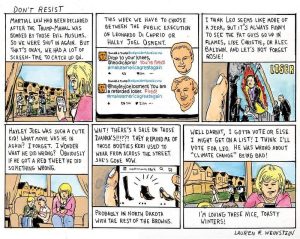

FROST: Since the original announcement, I’ve been following some of the progress that some my mutual friends on social media have been doing with respect to their submissions for RESIST! It’s been fascinating to watch. And one of the aspects of RESIST that I found most interesting was the lack of commentary in its pages. The entire issue will just be comics. What was thinking behind this decision?

MOULY: That was the goal: For us has been to represent the diversity of voices. We wrote a short editorial just to give it a little bit of context to people who will be receiving the paper. At some point at the beginning, we thought that in the back of RESIST! we should include some calls for action, places to boycott, write to your Congressman, or whatever. At some point we got in touch with Gabe, and we said, ‘We have way too many submissions, can we do more than forty pages?’ And when we talked to him, we realized that, no, because its not going to be any easier to condense at forty-eight pages. We ended up putting in over 100 submissions out of a thousand into the final paper. To put in a 120 wasn’t going to make a significant difference; we will be putting stuff on the website.

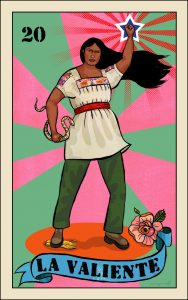

SPIEGELMAN: There’s been such a long history of art as political resistance. Unfortunately, there’s so little space for it in our modern world, and especially in America. There are so few publications that leave enough room for images. There are none or very few that are only comics images. Part of RESIST! is carving out more space for that world. It’s a necessary form a political resistance and a powerful one.

FROST: What will be the role of comics and creators in the next 4-8 years be? Do you see a flourishing of a talent inspired by opposition to a Trump White House? How should places like DESERT ISLAND and publications like SMOKE SIGNAL wield their influence to engender more positive change in the broader culture?

MOULY: I hope Gabe has an answer because I certainly don’t.

FOLWER: I’m not very political, and I don’t think reactionary art-making is the best practice. But creative people cannot sit idly by while real estate developers with ties to neo-fascism are allowed to bend the earth to their will. I don’t want to live in that world, so it is our collective responsibility to create a world worth living in, and fight for it on a daily basis with the tools at hand. All I can do personally is redouble my commitment to my own positive endeavors and try to provide a platform for free expression through art.

MOULY: One thing that we were really lucky with was to have the kind of open mandate that Gabe gave us. He didn’t tell us this must be this or this must be that. We were able take our cues because we didn’t have to please a rich patron and we didn’t have to submit to an über-editor. We were able to just go with the flow and try to do justice to what was sent to us. Our goal wasn’t to assert our political point of view, but to give a snapshot to what was sent our way.

I think one should take a leaf from Gabe’s playbook. What he created was an open platform. He had no idea that we would turn it into an internet edition of SMOKE SIGNAL, even allow us to call it something other than SMOKE SIGNAL by calling it RESIST! We happened to put in some solicitations for 10 dollars to mail a copy and we raised a gigantic amount of money through that, which allowed us to print twice as many copies and ship them everywhere in the US. If Gabe had been more didactic about, I am doing this and it is going to be that format or if we had to make a Kickstarter and find a business plan and stick to it, we wouldn’t have been as flexible in the way we let the public get involved.

I think many people will have access to the printing presses, and cartoonists should create the means and just let the artists provide the expression and be receptive to what comes.

SPIEGELMAN: You just broke down the three things that work. There’s having a deadline, a short deadline. Don’t limit who’s going to be able to submit. And, finally, make it physical, and allow it to penetrate into the real world.

FOWLER: It is cathartic, humbling, and intense. Ultimately it is unfortunate this project is necessary. But it is necessary, and I’m very pleased this platform exists for the creative expression of outrage and grief over a challenging situation.

MOULY: I think anybody in the comics world, especially the people who have comic book stores or physical distribution, are already schooled in something that is insanely valuable for the grassroots movement. In this day and age everybody gets to sign online petitions and call [their] congressman or whatever, but for those in the milieu of artists and cartoonists and publishers, we have a way of creating physical objects. These have a veracity, these have a presence and an authority that is so real. We should stop chasing clicks.

As Nadja said, this deadline was short by cartoonist’s standards, but it’s longer than what you get on the internet. Rather than typing one more comment in a chain…make a ‘zine. You know? Get your word out and go to your corner coffee shop and put a stack of it to take away for free. If anything, what I’ve learned is to reconnect with the energy of underground comics—or like Charlie Hebdo in my past. It’s probably the greatest bang for your buck: a wet press or a Xerox ‘zine. It’s better than making a $200,000 documentary or doing all of those other acts. The ratio of how widely it can be seen to the control you have over the means of production is unparalleled. It works for me, and I assume it will work for others.

To learn more about and order an issue of RESIST!, visit their website at www.resistsubmission.com. Copies will be available at the Women’s March on Washington on January 21st.

Make sure to hit up Desert Islands Comics at www.desertislandcomics.tumblr.com

Smoke Signal back issues available here: www.desertislandbrooklyn.com/smokesignal.html

As much as fans want comics to be pure escapism, the industry may not be able to ignore the Trump team. Just like it couldn’t ignore the Nixon gang some 45 years ago.

I think you’re going to see a lot of commentary about the political turmoil set to start tomorrow — both in interviews with creators, and in the comics themselves.

Comments are closed.