A little while back, Brian Hibbs wrote a piece involving the place of Kickstarters in the comics world that still seems to be making the rounds online. It comes at it from the retailer angle, and as somebody who’s run a few Kickstarters, I have a few different thoughts about how crowdfunding fits into the ecosystem. They don’t necessarily involve the Direct Market participating, either.

First off, there’s something that should be clarified. I know Brian. I shopped at his store when I lived in San Francisco. When Brian says he’s yet to sell anything he’s ordered for his shop from a Kickstarter, he’s not joshing. On the other hand, he’s in San Francisco and his shop is about a block from where all the tech company shuttles drop off and pick up. He has an unusually wired clientele, so it might not be a big shock that most of his customers are aware of what’s on Kickstarter and will have already put in a pledge for an item if it was something they wanted. Which is kind of the point of crowdfunding, really. However, it’s not clear to me that the lack of Kickstarter-funded sales at Brian’s store will be the same for *every* comics shop.

The original idea when Kickstarter began was to get artists the money they needed to make their project real. Get money for studio time to record that album. Rent some equipment to make that film. It was originally a little more “let’s get you through the last hurdle and when you’re done, you have something to sell.” It’s grown a little bit since then, but that’s how it started out and if you’re doing it right, the key concept should be “when you’re done, you have something to sell.”

If you don’t have something you can keep on selling after the crowdfunding is over, then Brian is right and you’re doing it wrong. The problem with color comics is that they’re expensive to print, especially in short runs. That cost screws things up for a lot of people. First, I’m going to talk about how this whole system works with comics and then we’ll talk about the better way that this normally happens with prose and will eventually be a common solution for comics.

The “Now” of Comics After Crowdfunding

When you play the crowdfunding game, you’re trying to get as many members of your core audience (and anyone else you can attract, of course) to pledge to the project. Naturally, this is going to mean less copies selling in the comic shops. Kickstarter is a direct-to-consumer business model. But it doesn’t mean that no copies are going to sell in the comic shops to one of your core audience (they might not all like the idea of pre-orders or crowdfunding). It also doesn’t mean that no copies are going to sell *outside* the Direct Market, either. Remember, Barnes & Noble just doubled their display space for comics and retailers complain about Amazon pulling tpb sales away from them all the time. There’s more than one venue in town.

After the crowdfunding is over, you want to have a commercial release. With the commercial release, you’re trying to pick up any of your core audience that skipped the crowdfunding and attract the casual reader. If you don’t have any copies left over after fulfillment, you can still sell digital copies, but you are dead in the water for print and good luck growing that audience. Brian is 100% correct about that, and letting volumes of series go out of print is a problem that goes beyond crowdfunding.

One way that creators go about addressing the commercial release is to get a publisher. Dark Horse, IDW and Image have all published comics that have started out as crowdfunded. This way the creator doesn’t have to worry about any of that. Do the fulfillment and let the publishing process proceed naturally, just remember to add in your crowdfunding purchases when you’re figuring out your real circulation and don’t be surprised if initial orders are lighter. Hopefully, you get a few re-orders and you keep your catalog in print so you can see the benefits of a backlist.

The other way is to print up a supply of comics to sell on your own. If you’re funding your inventory with the crowdfunding project, this is going to raise the amount of your goal, but a LOT of creators do it this way. Particularly in the webcomics world. In an ideal world, the creator puts a little money back with each sale so there’s a fund available when the time comes for a second printing.

Yes, that would be the creator acting and planning like a publisher. It’s a good mindset to have.

Where do you sell these comics commercially if you’re operating as your own publisher? Webcomics typically sell their print editions on their own website. You can get an account and sell them on Amazon directly. You *could* attempt a Diamond solicitation, but that so seldom works out for new publishers that it might be better to figure out which comic shops stock the sort of comic you’re making and contact them directly. This is the hardest part for comics. Selling digital copies, well… you should know the answer to that by now. That’s not nearly as complicated as being an independent operator in the Direct Market.

Is there a sustainable model to crowdfunding? Here is where I probably have the biggest difference with Brian’s column. OF COURSE, there’s a sustainable model. Great googley moogley, this shouldn’t even be a question. Here’s the first thing you need to know about crowdfunding. On every platform I’ve seen, there’s an option to message the backers of your previous project(s). Did you have 1,000 people pledge your last project? Well, assuming that your next one will appeal to the same audience, you’ve got 1,000 previous customers who are already in the system you can immediately contact when your project goes live. Then you go out and try and find 1,000 more.

Now, not everyone is going to buy every project you run. If you botch a project or are spectacularly late with one, good luck getting very many your previous pledgers to return. Same thing applies if you’re starting a new campaign before the previous product has shipped. But assuming the customer is happy with what you made, you are building up your own personal sales list and it should grow a little with each successive project. It should also make your launches a little easier and perhaps lower your stress 3%. (There is no such thing as stress-free crowdfunding.) Are you going to double your pledge count with each project? That’s highly unlikely, but you should be making at least incremental gains to your customer list each time.

If you’re doing a series and you have some copies of the previous volume(s) in hand, offer a bundle of the whole series as an upsell. It can help you raise more money AND it can get newcomers caught up on the series. You can upsell with copies of previous work that isn’t part of the series. If you have work available commercially, it would not be unheard of to see a sales uptick in “normal” commercial channels from the crowdfunding campaign if your marketing is effective. It’s a way for people to sample your wares.

To be sure, just like it’s bad to release volume 3 of a series to a comic shop is volume 1 isn’t available, you want to avoid crowdfunding volume three without volume 1 and 2 being available in some of the pledge packages. At are minimum, have the digital editions available if things are out of print. You can and should reach new people with each crowdfunding campaign and not everybody wants to jump into the middle of the story.

Is anybody really doing sustained comics business on Kickstarter? Absolutely. Have a look at Spike’s creator page: https://www.kickstarter.com/profile/ironspike/created. Yes, some of those are anthologies, but you’ll see some sequels there. That’s seven projects going back to the early days of Kickstarter and 2009. Gordon McAlpin recently funded the third collection of his Multiplex webcomic: https://www.kickstarter.com/profile/gmcalpin/created. Oh, you’re more concerned with Direct Market creators? Then here are 8 projects from Jimmy Palmiotti, the mayor of comics: https://www.kickstarter.com/profile/1397702842/created.

This is real.

The Way It Will Be Done In the Future

When I did my personal Kickstarter, it was a prose-based book and I did the same thing I’ve been doing with prose books for 10 years. I went Print On Demand. I personally use Lightning Source, which has morphed into Ingram Spark for new users. Other people prefer to use Amazon’s CreateSpace. This is absolutely normal for prose, but a bit new for comics. There are some real benefits to it.

The beauty of POD is you upload the file once and whenever somebody orders a book, a copy is printed and you get sent a check. Nothing goes out of print. You don’t pay any shipping. You don’t have to do your own fulfillment (unless you’re taking orders yourself or fulfilling a crowdfunding campaign). You don’t have to store inventory. It’s nice and efficient.

The drawback to this? You need to accept that there aren’t going to be many shelf copies ordered. Probably none. When I go through Lightning Source, I embrace that and offer a short discount, as is often the case with textbooks. Pretty much every online bookstore has a listing. You can walk into pretty much any bookstore and order a copy. Libraries can get them this way, too. (Proof. And again.)

Right now, you can do this comfortably with prose and black & white comics. For color comics, we’re in a transition period. CreateSpace is not priced to support color comics right now, but don’t kid yourself, Comixology will be integrated with CreateSpace sooner than later. Over at Ingram, you can definitely make the Standard Color work, price-wise, but depending on your coloring style, you might see a little bleeding and pooling with the color. It’s good enough for a reading copy. (I found it similar to some of the really thin paper I’ve seen in Vertigo tpbs in years past.) The Premium Color will get you pretty close to the look of a Baxter book, but it’s too expensive for most uses. I haven’t experimented with their “Standard Color 70” or “Standard Select” which appear to be viable from a price standpoint and might also work on modern coloring better than the Standard Color format does.

Drawbacks for color comics? Right now, there’s no glossy paper options, which the Direct Market is in love with at the moment. That might change in the future. Then again, the math of POD just doesn’t work out for selling through Diamond and you’re probably not going to be getting many stores to bite on a lower discount. You still need offset printing for that.

It does, however, keep your work in print and give you an alternate distribution network to the Direct Market. Comic retailers probably aren’t going to like this system at all, but for the little guy trying to put out his own short run comics, it can solve a lot of problems.

[Note: I do not consider POD to be a solution if being part of the traditional book distribution system isn’t part of the offering. Ingram and Amazon give you mainstream public venues to sell in and if you do POD, you’re going to need those.]

If you’re popular enough, you’re going to have offset printing in the mix when you fulfill your crowdfunding and it will be MUCH cheaper to print your own supply to sell at that time. Different methods for different situations. Just don’t be surprised when you see this become a more prominent business model. Who knows, prices usually come down and maybe this will eventually become fiscally compatible with the Direct Market, too.

Want to learn more about how comics publishing and digital comics work? Try Todd’s book, Economics of Digital Comics.

We Kickstarted the BAD KARMA hardcover and later offered it through Diamond (selling copies we had overprinted) via Dynamite.

My guess is we sold more copies through Diamond thanks to awareness of and response to the Kickstarter than we would have had we just offered it cold to the marketplace.

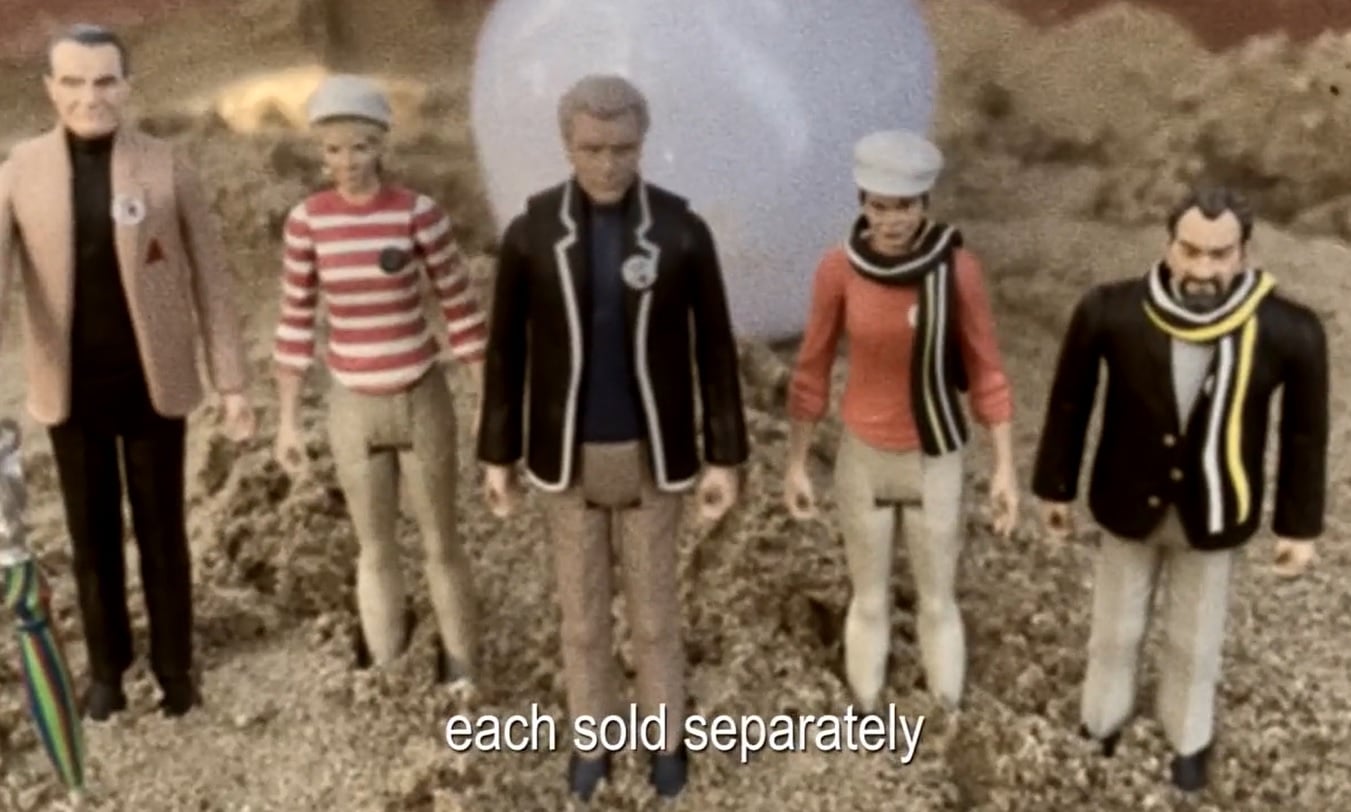

Kickstarters are a ton of work…I had to actually slow down on them a bit but picking back up in fall with a new one. The thing is you always have to look at your kickstarter as a store and try to offer the best product you can and show as much of it as you possibly can on your page. I love doing them because it creates a real connection with me and my audience and a certain kind of relationship that is just impossible to have anywhere else…but my point is that it is not an easy thing and you will judged by how well you communicate, and deliver a solid product. Like Todd says in this excellent piece, a lot of the after kickstarter income is made after the book is released and keeping digital as well as some of the books in stock like I do on the Paperfilms.com site is very important to those that might have missed the chance to become part of the kickstarter. As pictured, we have ABBADON now featured in the diamond catalogue under our partners Adaptive imprint and we are hoping word of mouth from the kickstarter helps its sales to a brand new audience.

Standard 70 ain’t half bad. I use it for advance review copies and it’s noticeably less premium, but only if you’re comparing the book to offset-printed ones on your bookshelf. The print quality is nice and crisp, on bright white paper, and most people who look at them think they’re finished books until I tell them they aren’t.

Comments are closed.