by Bryan Hill

When Heidi offered her forum to me to discuss issues of diversity, I was hesitant. I admire activism, but I’m a writer and my passion is talking storytelling and character. The opportunity made me feel unsafe, like somehow I would put storytelling in danger by raising the issue of diversity within it. I realized, during a long play session of FALLOUT 4 (my chosen tool for meditation), that my safety wasn’t at stake.

I was protecting my comfort.

Diversity is an uncomfortable conversation, especially on the internet. Writing popular fiction is kin to walking barefoot on hot coals. If you ignore the heat, you can make it to the other side. The moment you think about what’s underneath you, the flame takes you forever.

The greatest truth in my life is that all answers are found in storytelling, so my contribution to the diversity conversation is a story about me and Batman. Like all stories, its meant to personalize its thesis and hopefully explain, in emotional terms, why this conversation is important to have.

Once upon a time, when I was nine years old, my father died. There wasn’t a masked villain behind it. It was just plain old cancer that upended my world and taught me what the word “mortality” meant. The day my father died I walked into a comic book store. I lived in an apartment building at the time with my mother, and the store was across a four-lane street I wasn’t allowed to cross by myself. That day, after the adult hands on my shoulders and the chorus of deep voices saying “now I needed to be the man of the house” finished with me, I needed to go outside. I saw the bright colors in the window of that comic book shop in Olivette, Missouri, and I broke the family law. I crossed the street (on the green light), walking through the Galaxy Comics door while a John Byrne SUPERMAN: MAN OF STEEL cutout smiled at me with Kryptonian dimples.

Batman found me like he finds most people — quietly, grabbing me before I even knew he was there.

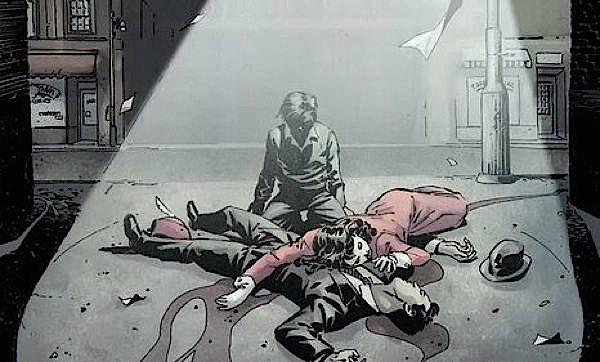

I don’t remember picking up the issue. I don’t remember what issue it was. It would be a better story if I did, but the truth is I don’t. I do remember opening it and seeing a panel of little Bruce Wayne under a spotlight, holding the hands of his dead parents. You know, THAT panel. THE panel. It understood me. The best attempts by the people who loved me to ease my tragedy all failed, but that panel triumphed. It was a mirror. I felt like that. Part of me will always feel like little Bruce Wayne. I read that issue of Batman in the store, sitting in the window, trying to not wrinkle the pages because I didn’t have any money in my pocket to purchase it. Ernest The Manager didn’t mind. He didn’t know me but I was a kid and I was reading and most adults know better than to get in the way of that. I don’t remember the details of that story. Someone in Gotham did something and Batman put himself in harm’s way to stop that something from harming innocent people. That’s probably what it was.

I do remember what that story taught me. It taught me to build a purpose out of grief. It taught me to harness anger around that purpose. It taught me that I had something in common with Batman. I wasn’t a billionaire, about the farthest from it, but it taught me that what I felt wouldn’t smother me forever, not if I worked hard to push through it.

I waited to cry that day until I was alone because Bruce cried alone. I wore my funeral suit and held my hands in front of me because Bruce did. I swore to my father’s ashes that I would give my life purpose because Bruce did.

Batman was my personal totem, the fictional friend and mentor that I didn’t have to share with anyone else. Batman, like I’m sure he’s done for many children, helped me. That’s the power of heroic storytelling.

But Batman didn’t look like me.

I never minded that Batman didn’t look like me; most old money billionaires didn’t. What began to bother me, over the years I continued reading Batman comics, was the only people who looked like me were the people Batman targeted. My face was never the grand villain with the Aristotelean tragedy. My face was never on the character that elicited both sympathy and fear. My face was on the thug. The people who looked like me sold drugs, mugged people, and they ended with an armored boot in the stomach and a hog-tie from a lamppost.

I knew I could be Batman, in my own way. I knew I could be good. I knew I could resist the temptation to harm others for my own personal gain. I knew I could even sacrifice myself for the sake of an ideal.

But the book didn’t believe I could.

Batman the character told me that I had to hold myself to a higher standard and it would be difficult, and I would fail, but if I truly dedicated myself I could overcome any obstacle targeting me. The book told me I was a criminal, that people who looked like me were criminals, that the people who needed to save Gotham from me would never look like me. The book taught me that being white wasn’t a privilege, but a requirement to be a person of virtue. It hurt, but Batman taught me what to do with hurt. Batman taught me despair only wins when you let it. So I didn’t.

I chose not to believe the book. I chose to believe Batman.

Inclusion isn’t an intellectual affair. It’s a personal one. Stories are mirrors and they reflect what a culture believes. When you don’t see yourself reflected in stories of heroism, you are being taught by that culture a clear lesson: You Can’t Be A Hero. You Can’t Be Admired. You Don’t Matter.

If you’re a child being taught that lesson, you’re factoring it into your worldview in a conscious and subconscious way. You’re reading books, watching movies and you’re learning your limitations. You’re being taught your place.

Society works for everyone when everyone believes they have equal value and potential. Superhero comics, by the virtue of what they are, must teach that. When they don’t, they’re not helping society.

It is an uncomfortable conversation, diversity. It makes people feel maligned unfairly. It gets infected with catharsis and anger. It can feel threatening to the pure joy of reading stories. I understand that. The call to action here — and Batman would always lead this to a call to action — is simply keeping in mind that stories are teaching while they are entertaining. We, as creators and consumers, can read comics actively and always consider one question: What is this story saying about our world and the people in it? How do these stories make people feel when they read them?

Can we do better?

Batman thinks we can.

BH

Bryan Hill is a comic author and screenwriter. Currently he writes POSTAL for Top Cow where he is also story editor. Find him on Twitter @bryanedwardhill

Great article, Bryan! You almost had me tearing up there!

This is why comivs accessible to kids, and generational sharing are so important. Something small makes a big difference. A kid came into a Honolulu comic store I was night manager of one spring afternoon. He tagged along with his friends, and always asked to see the inside of the book to see if it had any action… when his friends were off in another corner I asked him how much trouble he had reading… he looked at me like I kicked him. Later in the visit I offered him a deal. He really wanted a graphic novel, I told him I needed a favor. I needvto stay current on product, but I cant read while I’m working, so if he read the book to me and described the action, he could keep it. His buddys egged him on, so he sat behind the counter with the book, and started up. I told him I’d help him with words he didn’t know. At 5 he headed home, and I put 6 bux in the til and figured that was that. Wrong. He was there daily with his pals. Spring became summer, then fall, then on christmas eve his whole family came in and bought over 1000 bux worth of books, toys, games and gift certificates. He’d improved from two grades behind to one ahead in reading and english, and now visited the school library. He’s now an English teacher who uses old comics to help his slow learners. As my comic mentor told me, all it takes is a little heart to share and teach the joy of comics, and to fill young readers hearts with the wonder and hope that heroes leave in their wake.

Fantastic piece! Honored to know you, sir.

Yeah, sure. But it’s not as if a kid is going to walk into a comic shop today and find even that story, or even that owner not interrupting a kid smudging and wrinkling the merch. The product isn’t made for the kid anymore. The shop isn’t the domain of the kid anymore. And you’d almost have to be little old-money billionaire Bruce to afford comics on your kid allowance, too. So all the representative inclusiveness you may inspire therein just feeds the twenty-something SJWs their own fantasy worldviews of social-left metropolitan diversity (when the fact is we are still mostly self-segregated in more ways than just race, not a world full of multicolored five man bands) and spandex fetishism (not so often heroism anymore) back to them.

Absolutely wonderful!

I applaud the message of this column and encourage like-minded readers to look at the (black) characters of Duke Thomas from the Scott Snyder/Greg Capullo run of Batman and Luke Fox as Batwing.

Duke was there during Zero Year trying to crack Riddler’s puzzles, and later appears in the Endgame story arc when Joker tests a theory by replicating the Crime Alley scenario with Duke’s parents in front of Batman. I think the scene represents Batman’s triumph, using his own grief to prevent it from happening to someone else. Duke goes on to become the focus of the We Are Robin series, leading a grassroots vigilante movement.

Luke Fox is given high-tech bat-armor from his father, Lucius Fox. He had a New 52 series that has since been cancelled (after five trades’ worth of issues), but appears in other Bat-family books, including Batman Eternal and Batgirl, and was in the recent Batman: Bad Blood animated movie.

I don’t share these details to shill for DC/Batman, I just want to provide a couple of recommendations to supplement the call for diverse characters.

Thank you for writing this!

I’m Asian American and a fan of Batman (and superheroes in general) and your points are ones I have long considered as an adult reader and consumer. Even with superhero movies I otherwise love. I remember getting an uncomfortable feeling watching the first Spider-Man (2002) film during the scene when a bunch of (apparently) hispanic thugs try to assault Mary Jane Watson. Same with The Dark Knight (2008) given that the various criminal organizations of Gotham appeared to be a collection of immigrant/non-white persons (black, Russian, Asian, etc.). I do think it is interesting to note that the largely WASPy pantheon of Golden Age superheroes (Batman, Superman, etc.) were wish fulfillment fantasies mostly created by young, struggling artists and writers from working class Jewish immigrant backgrounds; ones who had trouble getting more “legitimate” employment in design or publishing due to the anti-Semitism of the time.

Jesus. This is a phenomenal piece.

FWIW, I’ve written an essay in response to Mr. Hill’s.

http://arche-arc.blogspot.com/2016/02/the-bad-apple-defense-pt-2.html

Excellent article. I was moved not only by your personal story, but by the intelligent approach to comics and the storytelling process. My life was changed by comics, if not saved by them. And I believe we are our own superheroes having to solve our own problems and save ourselves sometimes. Which means we have to recognize the power within us, which includes the ability to create powerful and beautiful stories to enlighten and inspire. Thanks.

Comments are closed.