This week’s edition of The Retailer’s View is going to be slightly different than most – while most of the time, I’m writing these solo with support and encouragement from my wife, this one was plotted and scripted from the ground up with her as a full co-writer. Originally, it was part of a presentation that we made at a local nerd gathering where it went over quite well. It’s been modified slightly to suit this venue, but all the main points are completely intact. So without further adieu…

Deconstructing the Clubhouse

By Danica LeBlanc & Brandon Schatz

When we decided to start Variant Edition, we were very mindful about how owners of small businesses often curate the experience of being in the store – especially in a store’s infancy. When it comes to places that cater to perceived niche markets, that curation can often become intentionally (or unintentionally) exclusionary, with the culture edging towards the strict confines of audiences such as they’ve existed for years. This quickly becomes problematic when you’re attempting to work within an industry that was formed with a largely white male audience in mind.

When dealing with entertainment media in general, the content has always skewed heavily male – and lately, there’s (finally) been some pushback against this culture. People are starting to question why there’s a need to quantify the difference between the concepts of “comics” and “comics for women” – and they’re following that line of questioning to a natural conclusion: why that qualification effectively “others” an entire gender.

This isn’t anything that’s limited to gender either. The late, great Dwayne McDuffie famously spoke of a “Rule of Three” – which plied to comic industry’s quickness to label a comic as “black” if there were more than three black characters on a team, or in the story. McDuffie noted that this wasn’t always a malicious label, but one that people ascribed to books without much thought. The majority of the book’s cast could still be white, but for the larger public, it would be something different, something other. The same occurs with books or movies with largely female casts, or forms of media that feature anyone other than a white male as the lead. Suddenly, it’s not a comic, it’s something outside of an actively accepted norm.

This “othering” can get a lot harsher within the comic book industry because of the way it has evolved. When the medium first formed, it was found everywhere – the funny pages in newspapers, on newsstands, easily accessible for the masses. For a time, this public accessibility made for an environment where there were comics for absolutely everyone – although given the prejudices of the time, comics for women were largely about teen feelings, romance, or domestic life – and comics for non-white people were fairly ghettoized altogether. As the industry evolved over the years, various content restrictions and societal pressures whittled the core audience into a niche. When fears that adult comics would make their way into the hands of children caused a crackdown on content, the entire medium took on the roll of a childish sibling to that of television, books and movies. It’s a connotation that remains today, and has often been applied to those who would read comics – a childish medium for childish people.

Much of this started to change with the emergence of specialty comic shops and the direct market in the 70s and 80s. Despite the childish connotations, groups of people (rightfully) found entertainment within the pages of comics that bloomed far into adulthood. With disposable income in hand, many sought to collect comics, and the industry adapted to this audience, first building spaces for them to find products, and then building products to suit this more adult audience. For the comic industry, this was both a boon, and a curse. While it did offer the medium a lucrative stream of money in the face of the rising costs of production, it was also the moment that literal walls were put in place. A core audience entrenched themselves inside the walls of comic stores. Outside, they were ridiculed for enjoying a childish medium. Inside, they were accepted.

The danger in this should be very clear – when society attempts to other a specific group, the reaction is often (and rightfully) fierce. If you read comics past a certain age, or spent a second too long indulging in the medium, you weren’t perceived as normal. When this happens, supports are formed as coping mechanisms. In this case, comic shops started to take the form of clubhouses, and those within started to become the arbiters. This naturally collided with the patriarchal structure of the medium. The overwhelmingly white male lead series begot an overwhelmingly white male audience who identified with the characters. Attempts to push out of this realm were either largely tone-deaf, or designed to also appeal to the already existing base. This would lead to product that didn’t seem to connect with the audience, the core rejecting something they didn’t connect with, and anyone outside the core lacking the content or the means to connect. This would in turn lead comic publishers to focus on the existing audience with their product line, which would lead to the further entrenching of this specific audience.

Of course, since the formation of the direct market, things changed again. The digital age once again brought about wider access to the medium through web comics and digital copies. With the structure in place to work around walled off comic shops, you now find an increased focus on reaching the audiences who were excluded from the old clubhouse structure. With the means to reach a wider audience in place, projects that appeal to the audience outside of the old structure have started to get traction, and the medium has been reacting to that – though not without severe growing pains.

Having spent years talking about how the medium needs more respect, the existing clubhouse structure is bristling at the ways in which that respect is being earned. As more diverse characters are introduced to the fictional landscape, the core is clawing at what was once only theirs. Some of the uglier bits of this community have gone so far to ply the terms “feminizing” and “blackwashing”, illustrating clearly how out of depth they are in dealing with othering. While women and people of different races or sexual orientations have been treated as others in ways that more often than not affect their basic human rights, white males have had very little experience with not always having what they have been basically given – and the reaction can often be childish.

That’s not to say that the entire core audience is like this – for the most part, most individuals are open to listen and grow and change, while a select few bristle and dig in their heels while making a lot of noise. It’s not so much about the individual, but the built structure as a whole. While open to change, many people are afraid of it, and when dealing with a structure that’s supporting an entire medium, change can be slow moving or stagnant. It’s easy to see where we need to be, but there will always be those who stop and wonder if everything might fall apart trying to get there. Fear takes over, and the gears gum up. People start yelling their opinions about what direction to go, or whether things need to be going in any direction at all. That’s always going to be the case – but as always, there’s things that can be done by individuals that can help.

Almost everyone wants people to like the things that they do. It’s part of the human condition. We like comics. When we find other people who enjoy comics, that makes us happy. We can talk with them and connect. When othering occurs during this process of connection – when it becomes an “us vs. them” thing – that’s when everything breaks down. Pointing fingers and digging trenches does nothing to further a cause. Nobody has been swayed to the other side of an argument when their opinions or feelings aren’t at least treated with a modicum of respect.

Working on the business has provided us with a deeper understanding of this point. While we always believed that comics can and should be for everyone, it became swiftly apparent that action was needed, in addition to words. With the structure still taking baby steps outwards to accommodate a larger audience, it doesn’t serve to be complacent. Ordering can’t occur without thought. When we go through the order book, and when we put together events, we try to do so mindful of what those orders and events say. For example, if there’s a company that produces books that almost exclusively feature women contorted into nightmarish “sexy” poses, there’s a high chance we will not be hand selling those comics. We will order them for anyone who wishes to read them, because we respect everyone’s right to their own opinion and taste, but actively stocking those books on the shelf or talking customers into buying those books enforces old, outdated structures.

In being mindful of the product that we offer, and the way in which we offer it, we’re hoping to do our part in getting this medium into the hands of as many people as possible. It can be done without shaming, and should be done without shaming. Your taste is as valid as someone else’s, and that simple statement of fact and purpose allows for mediums and stories you love and enjoy to be experienced by more and more people without unconsciously building walls and limitations – and while there will always be those who will kick and fight and froth for their right to keep their precious things to themselves, they will inevitably be left behind, stuck to the ground while the structure, slow moving as it can be, leaves them behind.

BACK MATTER

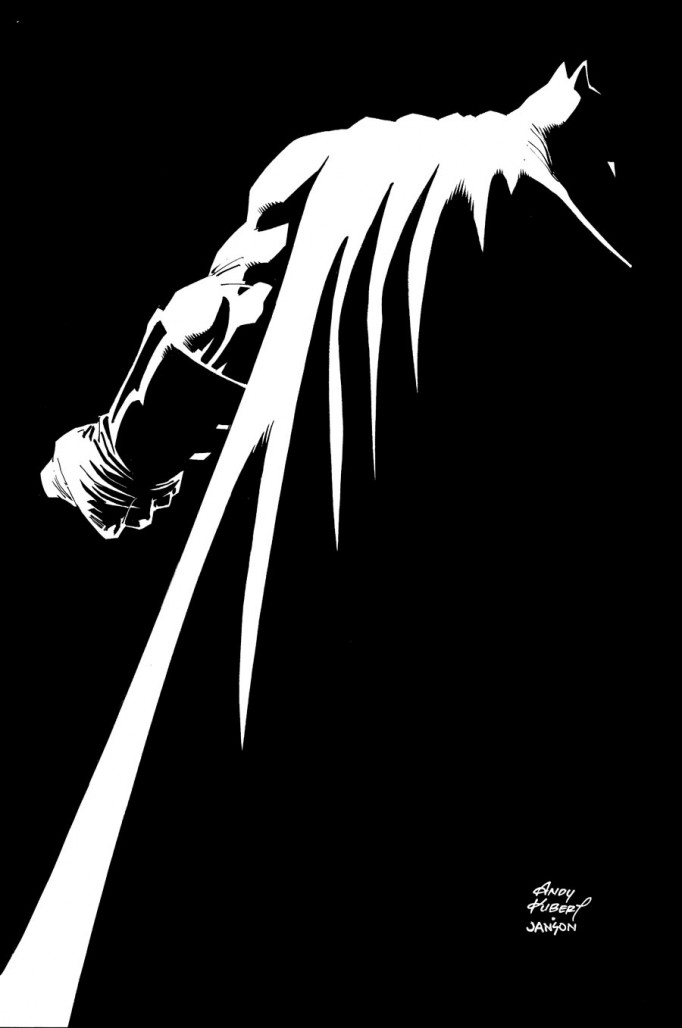

Did anything of huge consequence happen at NYCC? Not really – at least in terms of retail. DC talked more about their variant scheme for Dark Knight III, which continues to be an infinitely perplexing bit of comic book marketing.

Not only did the company wait until three days before final order cut off to provide readers and retailers with a complete look at the book’s structure, but they did so in the form of a two page sell sheet. To boil it down, DC is being so cartoonishly greedy about this concept, they took a book that would sell with the simple hook of “Frank Miller returns to Batman” and turned those five words into two pages of convoluted sales information. The book will be $5.99 US a pop, at least. The collector’s edition will be $12.99 US. That will ship two weeks after the regular edition, so if you want the story right away and the collector’s edition, you’re spending almost $19 per issue – and that doesn’t even begin to talk about the comic itself, and the mini-comics that come with it, and the variant structure they’ve worked out. I will be (and have been) able to sell DKIII to customers easier by saying “Frank Miller returns to Batman” than trying to tell them anything about the format. It’s ridiculous, and serves no purpose but to gut the golden goose one last time to steal all the delicious golden eggs they can from the corpse.

In other news, Marvel continues to announce dickish “1 for 4999” variants (there’s one for the upcoming Deadpool #1 and Star Wars: Vader Down #1) to jab a thumb in the eye of DC’s 1 for 5000 DKIII Jim Lee Sketch Cover and… well, I’m not exactly sure what that’s supposed to accomplish. Are… are people going to actually spend thousands on those variants? Will some stores bump up their orders to get a copy, and have these books spilling out into the aisles? Or is this like a gentle, useless hug for giant comic chain stores? I don’t know anymore. Everything is madness.

TO BE CONTINUED…

The Retailer’s View will return in a week or two with a hot take on Island. Mainly that I think it’s a format Marvel and DC should adopt sooner rather than later but, you know, with more detail.

Words are hard.

More to come.

ISLAND rocks. I sell more copies of ISLAND than virtually any Marvel or DC comic…. but, man, nationally it’s not at all what we’d call a hit.

-B

We’re early adopters, Brian. People are followers. Retailers, more so.

I hope they do well enough/worked out their business model to last long enough to let everyone else catch up, then — I’d LOVE to still be selling copies of ISLAND monthly in 2025 or later….

-B

I’ve never understood the desire for comics to be a boys club. When I was young, I would have loved to have a Heidi MacDonald or Kate Fitzsimons to chat with about comics. Alas, I didn’t know any girls who were into my hobby — and not many guys, either. I’m talking about the pre-Internet era.

I’ve heard that the resurgence of Image has brought more women into comics as readers. Image comics don’t take place in a shared universe, so you can pick up any title and start reading. You don’t have to read the entire line, or be aware of 50 years of continuity, to understand what’s going on.

Comments are closed.