By Jeff Trexler

My last post explored how continuities between the cover image of Action Comics #1 and subsequent material could give DC a substantial part of the copyright in the original Superman. One question left unaddressed, however, was the issue of Clark Kent, not to mention other key elements of Superman’s character and mythos appearing in that historic first issue.

In this post, let’s take a quick look at that question and the role it could play in bringing this case to an end.

One aspect of the art of judging is knowing where your greatest strength lies–namely, your grasp of the law. By resting the future of the case on a matter of artistic interpretation, the judge left himself open to question in regard to his adeptness in both art and law. The notion that the Action #1 ad is wholly distinct from Action #1 is inconsistent with basic principles of literary and graphic analysis–in regard to design rhetoric and reader response, I’d argue that Grant Morrison’s analysis is far more credible, and far more consistent with disinterested critical analysis, than arbitrarily claiming that an ad has no connection to the material it represents. Judge Larson’s interpretation may serve the deeper interest of giving justice to the Siegels, but it left the ruling vulnerable to reversal and provided little impetus for an swift settlement.

In concluding that the black-and-white ad for Action #1 has no organic connection to the actual story or character appearing in the complete version of Action #1, Judge Larson echoed another storied case in copyright history–one that, in fact, was sharply criticized in Judge Posner’s opinion in the Gaiman v. McFarlane. In 1954, the Ninth Circuit issued a highly problematic ruling that found Sam Spade to be an uncopyrightable character. As Posner noted, it was a decision that had wafer thin support from a legal perspective–it was basically a clever way of enabling Dashiell Hammett to continue to use his character in novels despite Warner Brothers’ evident ownership of the copyright. Subsequent courts whittled away at this ruling to the point that now it is essentially void, but today the process for challenging such decisions is much faster–comprehensive electronic resources and pressures for standardization can provide an immediate check on judicial creativity.

Rather than risking a future reversal by arguing that a black-and-white copy of the cover to Action #1 has no legal connection to anything on the cover of the actual Action #1, I could imagine a more artful appellate three-judge panel approaching the problem more strategically. Let’s assume that our artful judges believe, with Judge Larson, that there is no way around the issue of the Siegels’ failure to include the ads in the termination notice–although, for the record, I should say that there may be a viable way around it. Faced with a legal technicality that seems to our judges to thwart the fundamental interests of justice in this case, they recognize a clear way to follow the relentless procedural rules of copyright termation while preserving the Siegels’ claim on the Superman character.

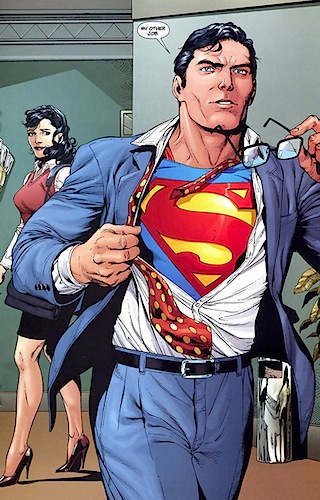

Namely, they determine that while the promo ads give core traits of Superman to DC, the Siegels own Clark Kent.

In contrast to both the black-and-white Superman and the equally problematic proposal to split the Superman character into wholly distinct old-and-new versions, Clark Kent as the alter ego of Superman is manifestly original material not apparent in the the cover image reproduced in the promotional ads. Because Clark Kent is arguably a derivative work of the preexisting Superman character, the Siegels could not use the character or conceit without getting a license from DC. By the same token, DC could not use Clark Kent or an alter ego (at least in the U.S.) without accounting for profits to the Siegels, just as the company would have to do with Lois Lane, Krypton, the news media setting and other original Superman elements in the Action #1 interior pages. The pressure on DC would only increase with the Shuster termination in 2013, after which it could not use this additional but essential material without a license from one of the heirs.

In short, by giving core traits of Superman to DC and the other elements to the Siegel and–in 2013–Shuster heirs, the court would present a recognizable and legally coherent variant on the classic judicial strategy of splitting the baby. Neither side would have the whole, and the only way for any party to get what it wants would be to reach an equitable settlement.

There is, of course, no guarantee that a court will reach this opinion, but if Judge Larson had taken this approach from the outset, chances are the case would be resolved.

Next: I respond to Kurt Busiek’s assertion that my legal analysis of the DC relaunch is a “slur” against the integrity of Grant Morrison and other creators.

[Jeff Trexler is a lawyer and consultant and a comics fan who writes frequently about how legal matters pertain to comics.]

always fascinating to read jeff trexler’s commentary on these kind of matters. thanks!

Re the Sam Spade case:

I see that the copyrightability of cartoon characters is a subject distinct from the copyrightability of literary characters generally, because cartoon characters can be used separately, for profit, from the stories they appear in.

While it could be argued that Clark Kent is copyrightable separately from Superman, I’d reject the reasoning because he’s useless to a writer as an independent character. He’s only an aspect of Superman.

There is a basis for supposing that, say, changes to a character’s powers result in distinct versions of a character since the changes affect how he’s used in stories.

SRS

This is really one of those situations where the article’s leading text, “My last post”, should be a hyperlink.

Interestingly, the Eighth Circuit issued a decision recently about publicity materials to the film The Wizard of Oz and agreed with the Siegel court’s analysis on the extent of copyrightable material contained in those publicity materials. Even more interesting was the fact that it was Warner Bros pushing for the Eighth Circuit to adopt the Siegel court’s analysis.

Even the copyright to a character cannot be divorced from the work in which it appears lest it transgress the cardinal prohibition in copyright law which is that ideas (meaning concepts not placed into tangible expression) are not protected.

Your efforts to link the copyrightable expression in promo ads to AC1 to an as of yet published AC1 seem to me to do just that and apparently the Eighth Circuit agrees on this one point.

The only issue I see is that if a Judge is willing to give them the ads, than they would most likely give them back the comic strips and Superman 1 pages, not mention the coloring from AC 1 & 4. Don’t really see it as an issue, but it seems the ad argument would seem to be the hardness one to pull off (from a justice perspective as opposed to a legal one, depending how the Judge views Justice).