I work alone on Sundays.

I pop in earlier than I do any other day. Things are still. The world moves a little slower during this time, unless the phone rings. When the phone rings, I curse, and while on any other day, I would answer it, on Sundays, I let it ring with a bit of resentment. While I’m pretty far from my days spent fairly deep in organized religion, my body still clocks the day of rest and worship in its own way. That time before I open the door is sacred. It is mine, and mine alone.

Shortly before I get things ready for the day and flip open the front door lock, I walk over to the surveillance device we welcomed into our shop, and I tell it to play my End of the World playlist on shuffle. It’s a mix I put together of songs I wouldn’t mind listening to as a wave of roaring heat washes over me. The music ranges in taste, featuring songs that have meant a lot to me when I was younger, to current favourites, and through to things that I just think would be funny to listen to in the moment. “Closing Time” by Semisonic is on there. “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” by The Band plays – specifically the version from The Last Waltz. That version takes the energy of one final performance and marries it with some stunning trombone work, and turns a horseshit song about the south losing the war into an equally horseshit song that I think is a perfect for the heat death of our lives. Humanity celebrating a defeat brought about by their own wretched behaviour, riding the bomb like a Doctor Strangelove1, filling our boots with nostalgia on the way out.

My current favourite on the mix is a song entitled “Single for the Summer” by Christian Lee Hutson, who writes incredible songs about people who are sad, but surviving. The chorus to this particular song is a phrase repeated over the gentle ticking guitar melody insisting, “things are gonna turn around any day now”. It would be a funny way to go, right? The noise grows louder around you, and you’re hearing someone insist that things aren’t okay, but by gum, they sure are gonna’ turn around. I listen to that most Sunday mornings, and I smile.

I thought I’d share that with you all for no particular reason.

Let’s talk about the direct market, shall we?

Up front, I want to acknowledge that I’ve been gone for a while. I have a short chronicle of the last year and a half up on my Substack, and its a mix of things you’d probably suspect (depression) and some you might not (death and fire). I didn’t want to go through all of that here, because I talk about myself enough in these columns when I’m focusing on the current events in the comic book industry, I didn’t like the idea of coming back with a full article’s worth of baggage to unpack before I could muster up some industry commentary. So. If you’re the type who is interested in the personal bits, head over there. If you’re not, let’s start talking turkey.

The first bit of clarity I felt around the end of the world was from an Image series in the last 15 years that I truly can’t remember the title of. I can tell you it ran two arcs. I can tell you it was about an apocalypse. I can also tell you the beginning, which sticks in my bones to this very day: the series opens with some in the far future giving a lecture on the times that the reader is about to experience in the book. Humanity has survived and is looking back at a time of hardship. The person at the podium talks about how, for a time, society was engaged with quick apocalypse stories because it satisfied the need within us to absolve ourselves of our actions. The world wouldn’t end because of anything we did – but because a cataclysm occurred. However, in the world presented in that comic, the world didn’t enter the apocalypse suddenly – it entered in dribs and drabs. Actions became consequences and everything crumbled in pieces. Humanity is not absolved of its crimes, we just have to live with them.

Now clearly, there was a happy ending to this book2 as the opening suggested a changed world. Things weren’t just rebuilt, but they were changed. The old structures hadn’t worked, they just had enough juice to maintain until something small went wrong. From there, everything cascaded until… apocalypse.

[Edit: Rad comics writer Matthew Rosenberg identified this comic as BlackAcre by Duffy Boudreau and Wendell Cavalcanti.]

As I prepare to write about the state of the direct market in 2023, I find myself thinking about that book, even in the absence of important details like “what the damn thing was called”. When collapse happens, it usually isn’t the results of a cataclysmic event – it is the results of actions taken over a large period of time. In the past, I have been publicly accused from folks in this industry of consistently predicting the fall of the direct market, much to their amusement. I won’t deny that. I think despite our gains, the direct market has been in a state of decline for a little over a decade. That’s easy to laugh at, but like the unknown comic above stated, collapse is a slow and creeping thing. It doesn’t account for appearances, only reality.

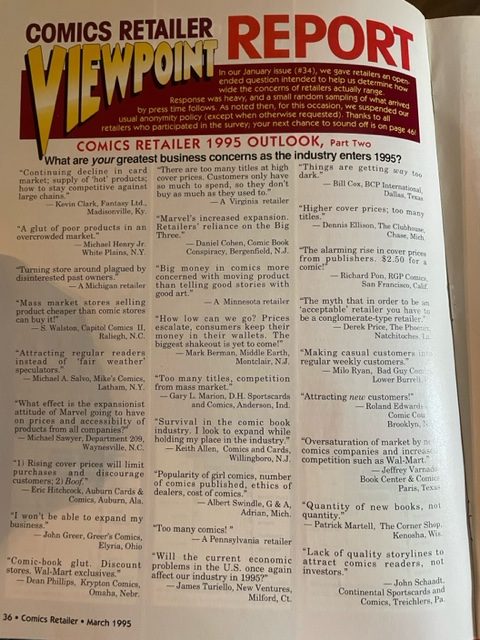

Here’s a look at a feature that ran in a magazine called Comics (& Games) Retailer with a cover date of March 1995. The content is concerned with things retailers are concerned about for the “upcoming year”. Very little of this would have to be changed for a similar article to run this very year. Some quotes:

“A glut of poor products in an overcrowded market.”

“Attracting regular readers instead of ‘fair weather’ speculators.”

“Comic-book glut. Discount stores. Wal-Mart exclusives” (I know this one works better for a year or so ago, but I still plotzed.)

“There are too many titles at high cover prices. Customers only have so much to spend, so they don’t buy as much as they used to.”

“Big money in comics more concerned with moving product than telling good stories with good art.”

“Lack of quality storylines to attract comic readers, not investors.”

“Will the current economic problems in the US once again affect our industry in 1995 2023?”

These problems are evergreen. They are never changing. They have been in play for at least over 25 years, and they have not been addressed in any way that sticks. This suggests something quite dire: the concerns these retailers are talking about aren’t bugs in the direct market system – they are features of the system.

Now, I wasn’t there when all of this happened, so my take involves a lot of second hand information. People have a grand nostalgia for the past of this industry, and I can see why. So much of it formed from folks identifying a need, and coming up with a solution, using an artful medium to do so. Any problems I have don’t come from the work that was done, but flaws inherent in the design.

Most things start with good intentions. The bad usually creeps in the larger a thing becomes. The structure needs to compensate for the load, and if the framework isn’t built to code, you start having trouble. This, is the story of the direct market.

At the start, the name on the tin said it all: direct. Folks were sourcing comics directly from the publishers, and selling them to customers. Deals were worked out, but nothing was standard beyond no returnability, which meant things were a bit messy, and you can’t grow something efficiently when it’s messy.

So the system adjusted. Distributors formed, and new deals were struck. The direct market became less direct, but the mess tidied a little. Distributors came and went while everyone tried to figure out the best way to keep the machine running. Every distributor had different troubles at different times, with some retailers (many literal children) hopping from distributor to distributor after skipping payments. Trouble never leaves this era, because distributors only make money when they move volume – but it was hard to maintain a volume with so many different distributors.

There was a long process of mistakes that led to Diamond emerging as the sole comics distributor. This brought a form of stability, but at the price of innovation. With one source controlling almost all of the supply, there was enough money in things to push through some dire times, but the company only innovated in reaction to the changing world. While positive changes did arrive (like the final order cut-off system, which I’m still stunned happened during my lifetime in retail), they came after retailers had generally devised their own solutions.

Then, the pandemic hit, and it hit hard. Diamond essentially shut the direct market down, single handedly. For roughly a couple of months, single issues are put on hold. DC built out a solution by working with the second and third largest distributors of comics to become official distributing partners.4 Shops that could run were hungry for content, and the publishers themselves needed product to get into people’s hands. This began the fracturing of the distribution system, bringing about the current system where Lunar, Universal, Diamond and Penguin Random House stand as the distributors of single issue comics.

And through this all, the same refrains. There are the same problems.

This past week, at my Substack, I talked about events and the need for the big two superhero comics to exist in a stasis by necessity. I call this state of being a perpetual second act, one that only ends when there’s been a failure. Looking at the direct market, I would suggest that we have the same problem. The direct market doesn’t change, because it can’t change.

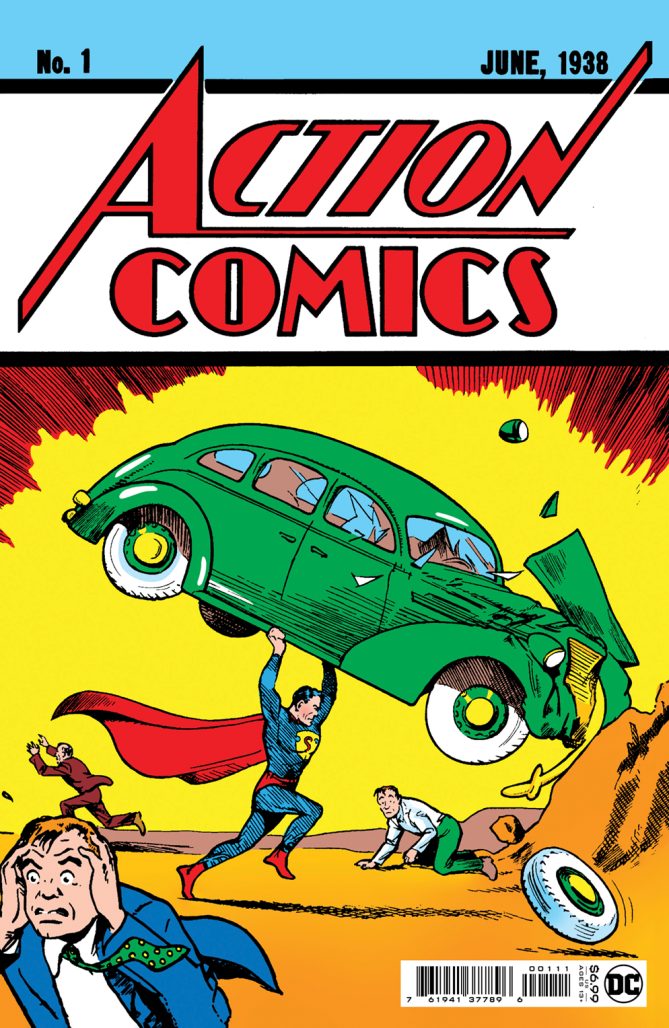

It started in the beginning. A need to get comics into the hands of collectors as efficiently as possible. A life raft away from the tanking newsstand market for comics. The trouble was, there was never enough juice in the format and the price point to make things work unless you were pushing things out through volume. The distribution wars proved an aspect of this. Another aspect was the fact that the direct market’s lack of returnability put all the pressure on retailers to move the product. On that end, you started to see retailers taking stock of their reality, and come up with solutions. Many of the stores that started before direct distribution sustained by flipping the comics they were purchasing to those who were missing issues. This practice continued and accelerated as retailers needed to compensate for unsold product.

This cycle eventually gets all fucked up on capitalism, and things start to routinely go awry. Pick an era of this industry, and I can find you a point of reference that shows how we weren’t doing okay during that time frame. Aspects would be doing well, sure, but even the industry’s largest successes are tied directly to the reasons we would eventually fall. Always. Consistently.

But we all want this thing to continue, in this particular way. We try and build structures to help us. Distributors come and go. Prices increase, titles increase, we spin the plates until they drop, and then we tape them together and try using the same plates, only this time, we start spinning them faster. More and more books come out. The prices increase. New characters seem to be a hit, so we make more new characters, but that eventually stops working and the plates wobble again, and they break. But we need this to work. We go back to the start, and try it again, the same things, over and over. The machine needs blood, and it can’t ever stop.

This was never okay. We were never okay. We all just loved this thing so much that we didn’t want to see it go away. And yet here we are, in 2023, and pretty much all of our problems are the same as they ever were. The only way we can fix this, is to stop trying to rebuild, and to just build something better. Which brings us, finally, to “act three”.

Using a window into the past, I’m going to tell you exactly how 2023 and a bit beyond is going to go for the direct market.

The system itself, will not change. It will outright refuse to be changed. Retailers, complaining about the woes we’re all suffering will chronicle the ways there are deficiencies in the structure, and their solution will be simple: we need to go back to the past. Things worked in the past. Tear down the decorations, let’s start from scratch. Put out some books with a classic feel! Build some more evergreen projects! Go back to basics!

By and large, publishers will go along with this, but not in any way that will be helpful. Most of them can’t. The ones like Marvel and DC, who are owned by larger companies that live and die on quarterly earnings will need that line to go up, constantly. So their help will only come in the form of continued acceleration, while noting the trends in buying habits. A lot of the smaller companies aren’t going to be able to help, because they’ve been playing their own shell games on a larger scale. Every big company that saw Netflix and wanted that money for themselves have found themselves at the end of fiscal with too much content, and not enough focused attention, so everything’s contracting. With no parties dominating the streaming space, companies are finding it more fiscally advantageous to stop producing, and start shopping previously made content around. This means that many of the comic companies that were running off investments with an eye for alternative media opportunities are entering a troublesome period. Ones that remain more independent are also finding problems maintain that pesky volume that you need to make things work.

In 2023, you’re going to see all of this play out in several ways. First? The $4.99 single issue comic will be standard by the end of the year. You saw the creep start last year. For the smaller companies, it will be a necessity in order to keep publishing their titles. For the larger companies, it will be similar, but to justify the existence of the format in a world where the line needs to keep going up at all costs.

You’re going to see Diamond continue to struggle. Penguin Random House will continue to be just fine, and they’ll announce another publisher or two joining their ranks. No one small. You’ll see this because they were built outside of the direct market in a system that was frankly built better. They also didn’t start up a distribution arm to make money today – they did it so that they could continue making money tomorrow. Because while the direct market will have its troubles, and while that will effect the single issue, that format will not go away. It will continue to feed the graphic novel market, even as it becomes harder and harder for any and all parties to turn a profit on the production of the single issue itself. It will continue to exist, because PRH can support that better than Diamond can. And Lunar will continue to exist, because they don’t pretend to be anything else other than who they are.

When they started distributing DC Comics in mid-2020, they were very clear about their reasoning. The short version: without content, our business and the industry doesn’t function. There isn’t any money in distribution, but there is a tomorrow for their comic selling business if they can help maintain the flow of product. To this end, this is where you’ll see life rafts for the smaller companies exist. Diamond might continue, but they’re never going to “come back”. They never really did. They had to stop paying their vendors, which trickled down to creators not being paid at some companies. They eventually were able to restructure a loan to the point where they could start functioning again, and if I were a betting man, their absolutely wretched, worst-in-the-industry shipping costs aren’t going to be enough to compensate enough to get them to a place of strength. When you’re in a position like that, a hit with something even beyond your own control can take you down. I think that is going to be a problem we hear more about in 2023.

That said, it isn’t all bad. While the idea flow doesn’t always allow it, I know that comics as a whole will always be fine. The medium is resilient, even when some of the parts that keep it going are not. Single issues will, in fact, never disappear, but their place in the industry at large will have to be rethought. The direct market itself, within the industry? The system of retailers? That is going to have to change into something else entirely. We can not be relying on the single issue as a revenue point anymore. It certainly can be at times, but by and large, the industry has to recognize that the format is a means to an end, and not where the money will come in.

To that end, I have a few ideas on how the industry can shift and change. It will be tough, but honestly, we’ve been through worse. A lot of it is going to come down to embracing the strengths and the faults of how comics are delivered to people, and building toward those points. There are so many great possibilities out there for publishers, retailers and creators to grow with some shifts in the way things are built, and where we expect the money to land. It won’t be easy, but it definitely isn’t impossible.

To that end, I’m here. I’m committed, at least, to coming up with ideas. For providing new perspectives. To helping us all continue to experience and enjoy comics for years and years to come. I’ll be chronicling more of the “day to day” of it all over on my Substack, while the bigger ideas will end up landing here at The Beat, which I see as one of the last, great places where actual comic book industry information is gathered.

I’m ready for the work. I’d like to think that I’ve already been doing it, but I’m finally back in a place where I feel like I have the means to share it too. I hope you’ll join me.

Talk with you all soon,

-B.

1You know, from the part where Doctor Strangelove learns how to love the bomb. Movies are my passion.

2Although the series wasn’t able to see it through – it stopped unceremoniously after the second arc

3The stories from the early days of the direct market are absolutely wild too. Just a bunch of folks working on handshake deals, selling comics to literal children.

4In a leaked spreadsheet from Diamond themselves, Discount Comic Book Service and Midtown Comics were the number one and two biggest accounts Marvel had by a hefty margin, and both companies had mail distribution programs.

5That said, Universal and Diamond are sub-distributing, and aren’t full distribution partners.

Very thorough, you covered a lot of ground. I do think DC will hold the bulk of their line at $3.99, in fact they are discussing test marketing , a few superhero titles at $2.99. To see if it moves a book , 5k-10k.

Comments are closed.