Comics have always been a huge part of my life, from my questionable six year old speculator phase (when I was convinced that any issue #1 was a prospective goldmine) to my pretentious preteen obsessions with the “great works” of comics (feverishly studying anything labeled with the words “sequential storytelling”). But it wasn’t until I reached my mid-teens and hit one of the most temporarily devastating periods of my life that I can really say I found a comic that changed my life.

When I was sixteen, I began to experience some strange changes in how my body and brain worked, or more importantly how they didn’t. I had not long before lost one of my closest friends to suicide, so I was already feeling an almost unknowable distance to normality and maybe that’s why I didn’t see the signs. The first time it happened I was home alone. I woke up on the floor, my face bruised and aching on one side. I didn’t think much of it. See, when you’re young and you spend nights barely sleeping, drinking in dark dank spaces trying to work out exactly what it is that you’re missing, and you spend your days desperately trying to make yourself enough, you find yourself saying, “Hey, this is just one of those things.”

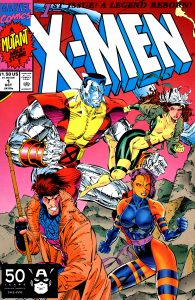

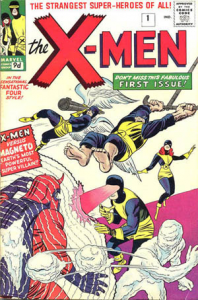

Unfortunately, relentlessly losing consciousness at inopportune moments is rarely “just one of those things” and after months of uncertainty and weeks in and out of hospital, I was diagnosed with Atonic Frontal Lobe Epilepsy. For the first few months of my diagnosis I couldn’t do much except stay in bed, sleep, and eventually read. In this time I turned to a lot of the things I’d loved as a child, seeking out some kind of security and familiarity in what was quickly turning out to be a very unfamiliar existence. One of the things that I revisited regularly during this time were my old X-Men books.

The stories of Xavier’s Institute for Gifted Students had long been a place I’d escaped to as a child, but suddenly this simple analogue for puberty took on a whole different meaning. The feeling of not knowing your own body, being unable to control it, and it manifesting energy in ways you didn’t understand or even actively partake in was now an acutely relatable experience in a widely unrecognisable world.

Using comics as a coping mechanism has become a natural response for me, and as the dumpster fire that has been 2016 slowly burns out, I’ve been inspired to try and write things that focus on the positives, on things that we love, things that have inspired us, driven us, and even just made us that little bit happier. I decided to reach out to some of my favorite creators to ask them which books have made that positive impact on their life, or why not finding that representation drives us to create art for ourselves and other people like us.

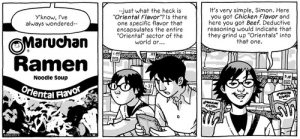

“Comic that changed my life” is a pretty big statement. I’m racking my brain for the comic that was a pivotal moment in my life and career. I never had that moment of feeling represented in a comic for the first time. But I think I might not have ever pursued a career in comics if not for webcomics, and I remember my mind being blown when I discovered Derek Kirk Kim’s work. Particularly Same Difference, which he was hosting online. It was thrilling to me that it was so different from the superhero comics my brother read or strips in the newspaper, and you could tell these full, beautifully illustrated stories on the Internet. I devoured everything on his website, and not only was his work funny, bittersweet and relatable for a young 20-something like me, but he talked earnestly about being a comic creator. Seeing him talk openly about his career, even his mistakes, gave me courage to continue my own comic work; to accept that it might be a bumpy road, but the journey is still worth it.

I’ll admit this is kind of a big ask.

Comics have always been a part of my development, whether humming softly in the background or leading the band in the foreground. My dad would read them to my brother and me as kids–and took us to our first comic shop in Cleveland in the early ’80s–and my mom encouraged us because it taught us not just how to read but to love reading. And while superheroes dominated most of my reading through elementary, middle, and high school (I’ll always have a place in my heart for the New Mutants), it was in my late teens that I began to branch out. I was studying Japanese and it was a revelation to read Frank Miller’s Ronin and Hiroaki Samura’s gorgeous, brutal Blade of the Immortal, both of which did change my life…

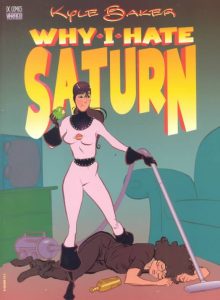

But this isn’t about that. This is about another book entirely. (I can have more than one life-changing comic, can’t I?) As a freshman at college in Pittsburgh, I quickly discovered my local comic shop–The Phantom of the Attic–and it was there I happened upon the comic that rewrote the rules for me: Kyle Baker’s Why I Hate Saturn.

I don’t know what possessed me to pick it up, though the blurb on the back that proclaimed “Kyle Baker is god” didn’t hurt, but I’m glad I did. More than anything it reminded me that comics can be funny. After a decade plus of mutant angst, cool samurai, superhero deaths and rebirths, and everything else in between, Why I Hate Saturn was a breath of fresh air to laugh with a comic again. It was easy to forget that aspect of comics existed and could be expected so well. And it didn’t look like any other book I was reading then: the sepia tones, the playful lines, even the placement of the dialogue on the page. I didn’t know who this Kyle Baker was, but with this honest, hilarious book about brilliant, listless writer Anne Merkel, he’d tapped into something deep in my brain I didn’t even know laid dormant. Eighteen years later, it holds up remarkably, and it remains the only comic I consistently re-read at least once a year, and it still makes me laugh like it’s the first time.

I guess I’d have to say that the first American comic I read that engaged me intellectually Batman vs Grendel. I feel like the title foreshadowed deeper ideological and formal conflicts inside. That comic made me question the comic book hero archetypes and motives. Batman just seemed so two dimensional next to Grendel and the storytelling was far better than the superhero comics I would read at my friend’s house. Around this time I first saw Moebius’ work hanging on the wall in the comic store.

When I was maybe a junior at Pratt I discovered Moebius’ Arzach. That lead to the creation of my first Gratnin project, a ninja comic that had no dialogue. This was pivotal for me because from that point on I got really deliberate about panel to panel and space. Gratnin had to sink or swim on visual storytelling alone.

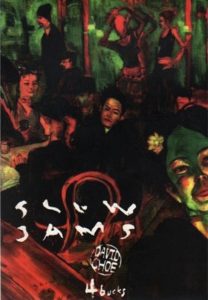

Shortly after this I picked up THB. The storytelling was great; the mark making was exceptional. This was someone who was DRAWING. The pages were interesting drawings. Also, THB fit in with all of the weird design magazines I’d get from Zakka or St. Marks bookstore. THB was smart design. This ruined me for many of the comics for which Slow Jams hadn’t already ruined me. Also, as a creator, Paul Pope was the first cartoonist I saw and thought, “Oh, this is a cool guy. Making comics could be cool.” I was an art school drop out.

When I saw Tekkonkinkureeto, it was a floppy. I was probably coming in Jim Hanley’s to find more Paul Pope, Moebius, or Dave Cooper. It was my first real experience with Gekiga I think. The drawing was right up my alley. I was already familiar with Matsumoto Taiyo’s artistic lineage, but it was great to see it used in comics so liberally. I also really appreciated how succinct the story was.

Enigma – Milligan and Fegredo

But as

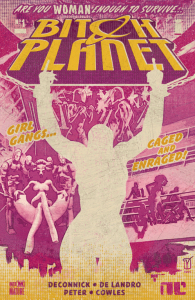

The other comic was Bitch Planet #3 by Kelly Sue DeConnick, Robert Wilson IV, Chris Peter, & Clayton Cowles, and it was somehow about all the same things that Bitch Planet #1 (and the series in general) was about, but it was also about a subject that almost never gets tackled in media – fat acceptance. And it approached fat acceptance in such a forward thinking and bold way, as a fat woman, I’ll tell you, my mind was blown. And it shouldn’t have been, because I should have already learned in BP #1 that this was where this series was headed – that it was more than just a comic book – it was a MOVEMENT.

And not every comic could (or should?) be that, but it sure as hell made an impact on me and how I approach my own comics. It’s exactly what I needed as a creator and a reader.

Without a doubt, Miller and Gibbons’s Give Me Liberty, which I firs read at age 13,completely changed my idea of what comics were and could do. It was the first female black protagonist I can remember reading in anything and as a teenager the subject matter blew my mind, and after a recent re-read, almost fits better in today’s political climate than it even did in Reagan’s 80’s.

Like Heidi, still hoping and praying that someday a movie gets made.

After graduating high school is when life really started for me. I was engaged. Started to work and went to college. At the time my husband thought I needed some down time. He took me to my first comic shop. I was introduced to Deadpool. This character reminded me not to take life too seriously. Comic books have been in my life ever since then. My kids learned how to read from comics. Now they are teenagers and appreciate the art and literature behind it.

As a teen i was very much in to the vertigo line of comics and I loved Sandman and Hellblazer. I got the opportunity to go a now defunct comic store named Heroes and meet Neil Gaiman. You could get 3 items signed and i had 4 people getting things signed. When I stepped up and handed him Hellblazer #27 my hand was shaking because it was my favorite comic at the time.As he took the comic from me he remarked that I had been the only person to bring that comic for him to sign at any of his stops. I said that it was my favorite story that he had written for comics and he said it was his too and proceeded to outline the heart and draw several things on it before personalizing it for me. That comic sits in a picture frame above my desk and reminds me not only of the meeting, but why I try just about any new comic that doesn’t involve a super hero.

Comments are closed.