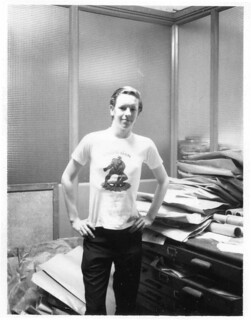

Stephen James Moore was born at 2:00pm on June 11th, 1949, in a house on Shooters Hill in South London, where he lived all of his life, and died on or around the 16th of March, 2014, still in that house on the hill. In between, he produced a huge body of work, of a very high standard, most of it written in that same house. He was a hugely private man, but his life and mine intersected over the past few years, and I got to learn a lot about him in that brief time.

But, actually, I was aware of Steve Moore’s work long before that. I had only ever been a desultory reader, at best, of 2000 AD, where he wrote a multitude of short sharp tales, but it’s probably not an exaggeration to say that Warrior, where he was a vital component both in front of and behind the curtain, changed my life. However, I had probably been reading his uncredited work in British comics for years before that, all unknown.

Meanwhile, in another part of his life, Bob Rickard, who he’d met through various fannish activities in 1968, was about to change Steve Moore’s life, forever. Rickard had discovered that the Odeon cinema in Birmingham was showing Chinese movies at one o’clock in the morning, so that Chinese restaurant staff could see them after work. He brought Steve to see a film called The Sword, starring Wang Yu, and he was hooked, immediately. This would lead to Steve seeing as many of those Hong Kong and Taiwan produced movies as he could, and eventually writing about them, and Chinese culture in general. He spent a large amount of his leisure time in the early and mid-1970s hanging around in Chinese cinema-clubs in the Chinatown area around Gerrard Street in London, and still had some of the lobby cards and posters he managed to persuade the staff to give him. Eventually this led him to the I Ching (more correctly Yijing, as the preferred spelling is these days), or Book of Changes, which became a major area of scholarship for him, leading to his writing the non-fiction The Trigrams of Han, published by HarperCollins in 1989, which was well-liked by fellow scholars, but made him no actual money, to speak of. He also joined the I Ching Society in London, more for the publications than the meetings, and soon took over production of their journal, The Oracle. He ended up as a Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society, and was one of the main contributors to I Ching: An Annotated Bibliography, an exhaustive 350-page analysis of the subject, published by Routledge in 2002, and continued contributing to both scholarship and debate in the field, right up to the present day.

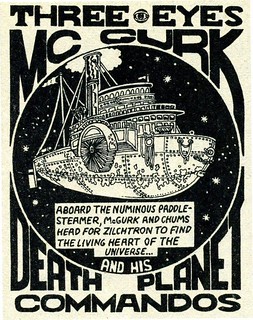

While all this was going on, there were changes afoot in British comics. In February 1977 IPC Magazines launched 2000 AD, one of the tiny handful of UK comics that is still in print. Steve Moore’s first story for 2000 AD appeared in Prog 12 (that is, issue #12), with the first part of a 12-part Dan Dare story, on the14th of May, 1977. He would continue to write for the comic, on and off, for nearly thirty years, finishing with Prog 1458 on the 28th of September, 2005. In Prog 25, he wrote the very first story to be called a Tharg’s Future Shocks, which would become an umbrella title for very short stories – which is still used as try-outs for new talent – which would go on to be written by all sorts of people, like Neil Gaiman, Peter Milligan, and Alan Moore.

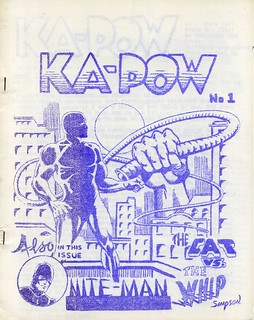

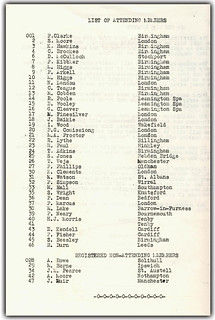

Alan Moore, who is famously no relation to Steve Moore, had first met his namesake through the pages of Phil Clarke’s sales-list fanzine The Comic Fan, around the middle of 1967, where Steve had advertised looking for a book called Dead or Alive, an Avengers novelisation – the British TV series Avengers, rather than the American comic Avengers, that is. In the end, it turned out that the book had never actually been published, of which Steve Moore said,

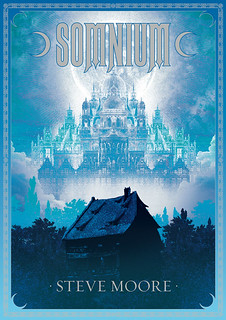

So the whole friendship is basically rooted in a quest for a non-existent, chimaerical book … which is a motif that’s turned up occasionally in the work of one or other of us, in mine as recently as Somnium. It’s not a bad symbol for writers, too, as their job is to bring non-existent books into existence, by writing them. But perhaps more interestingly, in view of our more recent notions about Idea Space, we were brought together by the idea of a text, rather than a real one. Attribute whatever significance you wish to that. Maybe it was just the universe having a laugh.

A regular correspondence soon developed between the fourteen-year-old Alan and the eighteen-year-old Steve, and Alan would become one of Steve’s two closest friends, along with Bob Rickard. And Steve is the man Alan blames for leading him astray, in all sorts of ways, although Steve begged to differ, when I asked him about it…

PÓM: I have this romantic scenario in my head where Alan is the wild one, always leading you astray, whilst you are the quiet one, being dragged into all sorts of wild scrapes by your friend. But this is really entirely wrong, isn’t it, as regards comics, drugs, and magic? You are quite literally the man who led Alan Moore astray.

SM: Well, I’d like to portray myself as an evil Svengali who took one look at Alan and realised that here was a striking-looking but malleable individual who I could get years of pleasure destroying an inch at a time, but it wasn’t really like that … even if he has said publicly that I was the man who ruined his life! I just wander into these things like writing comics, smoking dope, practicing magic and resigning on points of principle, and the next thing I know Alan’s decided that as I haven’t actually died as a result, he’ll do the same … only he does it much larger. It’s not my fault, honest! Mind you, he doesn’t always follow my lead. I’ve never got him hooked on China or classical music, in the same way that I’ve never really shared his interest in science or stand-up comedy. We just have areas of interest that overlap … and enormous mutual respect in areas where they don’t. And even where they don’t, there’s still a bit of influence going back and forth.

He also contributed occasionally to another ambitious British comics anthology series, Atomeka Press’s A1, including an article about Fortean Times in A1 #2, in January 1990, which I read, and which caused me to go looking for the magazine, and which, along with Jan Harold Brunvand’s The Vanishing Hitchhiker, was responsible for fundamentally changed my worldview. In is no exaggeration to say that a good deal of what I am today has been shaped by my reading that article in A1 #2, and by Steve Moore.

But he soon moved away from comics, mostly, and this was when he was heavily involved with Fortean Times, as mentioned above. He did come back to comics, to write for Alan Moore’s America’s Best Comics imprint, where he contributed to titles like Tom Strong, Tom Strong’s Terrific Tales, and America’s Best Comics: A to Z. His last work for comics was to write two five-issue mini-series for Radical Comics, Hercules: The Thracian Wars and Hercules: The Knives of Kush, on which the forthcoming film, Hercules: The Thracian Wars, is based.

I got offered a review copy of the book – probably prompted by my writing this piece about the book – and, out of the blue, also got an email from Steve Moore, thanking me for the piece, and asking if I would like to ask him any questions about it. After I got over my genuine shock at getting a mail from a man I had always presumed was going to be forever beyond even my reach, I told him that I would indeed. And I did, ending up with this interview, which went online on the 11th of November, 2011, as pleasing and magical a date as you could wish for.

PÓM: You are legendarily reclusive. How did you feel about Alan’s Unearthing, which is essentially a tell-all biography of you? Or is the reputation for reclusiveness exaggerated?

SM: Reclusiveness is relative! I prefer to think of myself more as ‘private’. I love seeing my friends, and I like going out (though with the state of 21st century culture, it has to be said that there isn’t really a great deal to go out for, except perhaps dinner) … but I just don’t like making public appearances, and I’m not at all interested in fame or reputation. All I want to do is write. I don’t have the slightest interest in the game of being ‘a famous writer’ and I’ve no liking for Conventions, so nobody sees very much of me. Which suits me …

Anyway, as for Unearthing … Alan was invited to contribute a piece to Iain Sinclair’s anthology London: City of Disappearances, and really the only part of London he knew anything about was Shooters Hill, as he kept visiting me here. He then decided, for reasons best known to himself, that he wanted to make it a biography of me as well, so I just said okay. I told him I’d correct any factual details, which I did, but apart from that he could write anything he liked about me, which is what he did! Apart from the comic exaggeration in places, it’s all true, so I said fine and thought the piece would disappear as one of Alan’s ‘minor works’. Obviously it didn’t happen like that! Now it’s become an audio-recording, been performed, will soon appear as a coffee-table book photo-illustrated by the brilliant photographer Mitch Jenkins and, apparently, will even be coming out as an app. How do I feel about all this? Well, I imagine that like most people I tend to judge what’s ‘normal behaviour’ pretty much against what I do myself, so I’m just sort of bewildered by all the attention it’s getting. But overall, it’s been a lot of fun hanging out with Mitch and his photographic team, meeting the musicians and attending the performances. And the whole thing has rather surprised my friends and relatives!

PÓM: I suppose there’s an enormous irony in a piece about a private man becoming the subject of such an amount of attention, particularly in a book apparently about disappearing. There’s a section in Unearthing where Alan dictates what happens next, and then has you do what he’s said you would. Did this actually happen, or is that just Alan entertaining himself?

SM: Of course it happened! I read through the manuscript when it first arrived and knew I just had to go for my usual walk, as described. And, yes, I hung about for a while by the burial mound, as described, and there were actually rain showers that morning. Unfortunately I couldn’t quite disappear, as the manuscript prescribed! But you have to remember that Unearthing was both about magic and, to a certain extent, was a magical piece in itself, with the writing and world described merging together. So I naturally acted out what was described, just to ‘make that real’. And Alan knew I would when he wrote it, even though he hadn’t told me in advance what he was intending to do.

And, in August 2013, out of the blue, once again, I got an email from him saying,

I’m not quite sure why, but in the last few days I remembered that when we were last in touch you expressed an interest in doing a more general interview with me, and now that I’ve got a bit of distance from the comics industry, I thought it might be time for a retrospective. It’s something I’ve put off, although I’ve never really had a problem with interviews on more specific subjects, like Abslom Daak or Somnium … but I’ve always tended to be a bit nervous about more general retrospectives, because I want to avoid situations where I’m asked questions like ‘You know Alan Moore better than anyone, so tell us all about him and … etc.’ That’s still not an area I particularly want to get into, but if you want to discuss my life and career, I’d probably be up for that. Assuming you’re still interested, of course …

So if you’re up for it, I’d probably prefer to do this by email, as I then get time to think about my answers, and possibly look things up (though a lot of records have long disappeared … along with large chunks of my memory!), but we can always do further sets of questions if you want to ask me more about something that’s come up. And as it’s a pretty long career, we might want to do it in sections, too. But if we both look on it as ‘something we do when we have time, around other things’, I imagine we could do it. Let me know what you think. No obligation, of course. If you’ve got better things to do, no problem!

So, did I want to interview the most reclusive man in British comics, and a man who had, unknown to himself, taken a hand in my own life, here and there? Yes, I most certainly did. We started a slow to-and-fro correspondence, working through his life from its beginnings in 1949, slowly towards the present day. I’d send a handful of questions, he’d send answers back, and I would then respond with additional questions about his answers, as well as some fresh questions to move it all forward a little, and so on. It slowly inched onward, not only at the cutting edge of it, but in the middle as well, as either he or I thought of something that might be useful to add in to a particular section. Sometimes he would suggest specific questions, and sometimes I would suggest how I wanted him to answer a particular question, to allow us to reach a particular thing we wished to discuss. It was probably the most satisfying interview process I had taken part in, of all the interviews I have done.

Amongst other things, behind the veil of private emails, we discussed our own lives, a little. We both were unwell, in our own ways. I had prostate cancer, but it was going to take years to get me. He had problems with his stomach and lungs, and was having regular CT scans, but as recently as the beginning of February he had been told it was all under control, and that he needn’t bother coming back for another scan until October. There was certainly no sense of imminent death, and I had imagined that another few months would get us to the end of the chronological part of the interview, and onto more etheric matters, like his ideas about writing, and about magic, and other things. Then a bit of editing, and we would actually have a usable document, although exactly what would happen to it, and how or where it would actually be published, was still anyone’s guess.

I had broached the idea of death with him, early on, and had intended to come back to it towards the end of the interview.

PÓM: I can’t help noticing that both of your parents and your brother died in their sixties. Does this give you pause for thought at all, seeing as you’re in your sixties yourself now?

SM: Yes, of course it does, especially now that I’m developing a few common medical problems associated with ageing. On the other hand, though, my maternal grandfather lived to be 90, so there may be hope for me yet! But I’m pretty much of a fatalist, and a recent scientific notion about the nature of time (called ‘Eternalism’) suggests the future already exists and the universe may actually be deterministic. A lot of people don’t like that idea, but I actually find it rather comforting, because it means that everything happens in the only way it possibly can, whether we like it or not. Even if that’s not the case, when it comes to time to go, I’ll just have to go, so there’s not really any point in fretting about it. But I’m aware that my time isn’t limitless, and some projects can’t be left forever. And that awareness may also have had something to do with my deciding to do this interview.

In the meantime we both took holidays, had problems with our computers, and got distracted by other things, as one does. By the beginning of March, six months after we started, and after a little over 48,000 words, we had got as far as Warrior – already the size of a small book, with the prospect of possibly the same amount again to come. I had sent off a last handful of questions, just to tidy up the very end of what I needed to know about his time at Warrior. When I didn’t hear back from him after a week or so, I sent another, and then sent a mail to a few other people, to see if they had heard from him. They hadn’t. One of them arranged to have a member of the police call to the house on the evening of Tuesday the 18th of March, and he was found dead there. There hasn’t been an official announcement of the cause of death, but it’s likely that it’ll turn out to be related to his heart, or his lung problems, I imagine.

I only got to meet Steve Moore once, in London last November, when he surprised not least himself by going along to An Evening with Alan Moore, to mark the launch of Lance Parkin’s biography of the younger Moore. There were many things about the evening I treasure, and meeting Steve is very high on that list. I had fully imagined that we would meet again, on one of my occasional visits to London, but that is no longer to be. And I still can’t really believe that.

He had already made plans for his funeral – in Sketches of Shooters Hill, another of his Somnium Press booklets, whilst talking about a four-thousand year old Bronze Age burial mound on Shooters Hill, he says,

Born high up on Shooters Hill myself, when I die I want my ashes scattered on the burial mound, by the light of a lovely full Moon. So, just for a moment, I too can become an offering to the local Gods and Goddesses, and merge my essence with the native soil … before all that physically remains of me is blown away and scattered, like oak-leaves on the whirling wind.

I hope I can be there, at least for that, to pay my final respects to a wonderful, extraordinary, and gentle man.

[The first and last photos are by Kevin Storm, and are used with his permission. The rest are a mixture of images Steve Moore sent me, to go along with the interview we were doing, scans of my own books, and things I’ve, essentially, robbed off the internet. ]

— Pádraig Ó Méalóid —

Very moving and informative.

and Super Gran.

Oh no…. I didn’t realize he had passed away. He’s one of my favorite writers…I always thought of him as the everyman’s Alan Moore. The two authors covered a lot of ground, but Steve Moore’s work was always a bit more grounded and less technically showboat.

Beautiful, Padraig. Thank you.

Thank You Padraig. I am STILL in SORROW. Steve and I corresponded several times a year for the past decade. We both published Fanzines and went to the first ‘Conventions’ in the Sixties. I love his writing and his mind. I was honored when he sent me Somnium for comment years prior to publication. A Unique Rare Original.

What a terrible loss. His strips were gems and his imagination boundless. His novel, Somnium, was a hard but fascinating read. In all my dealings with him he was always a polite and enthusiastic soul who will be much missed by many. Thank you for your wonderful tribute, Padraig.

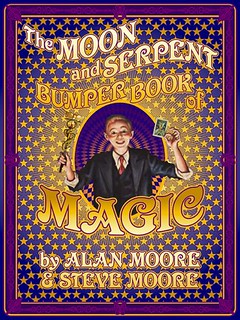

I wonder if Alan Moore will take it upon himself to finish the Bumper Book of Magic? Shame for all that work to go to waste.

Padraig,

Thank you for this. I’ve enjoyed reading all your wonderful writing about Steve Moore on this website. Thank you again.

Koom

Comments are closed.