The Beat’s Gregory Paul Silber has been accused of having a bit of an… obsessive personality. Each week in Silber Linings, he takes a humorous look at the weirdest, funniest, and most obscure bits of comics and pop culture that he can’t get out of his head.

Subtlety is often seen as a mark of maturity, especially when it comes to the art we consume. In a lot of ways, that makes sense. Children’s entertainment is rarely subtle, because developing brains that are still absorbing basic information about the world need things spelled out for them. I doubt Sesame Street would be an effective educational tool if Big Bird delivered a lesson like “sharing your toys is good” in an ambiguous fashion. Then we get older, and our ability to appreciate the messy morality of a book like Of Mice and Men when it’s assigned to us as freshmen in high school reflects our growing ability to view the world in less black-and-white terms now that we’ve had some life experience.

But lately, the older I get, the more convinced I am that subtlety isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.

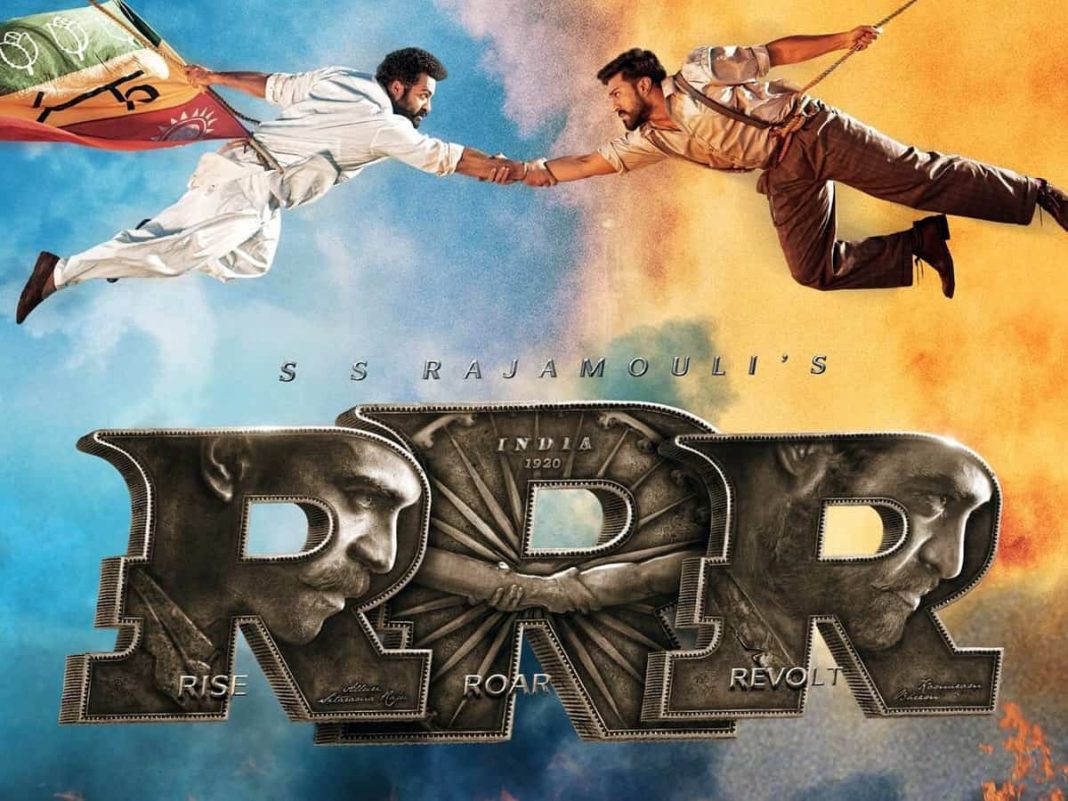

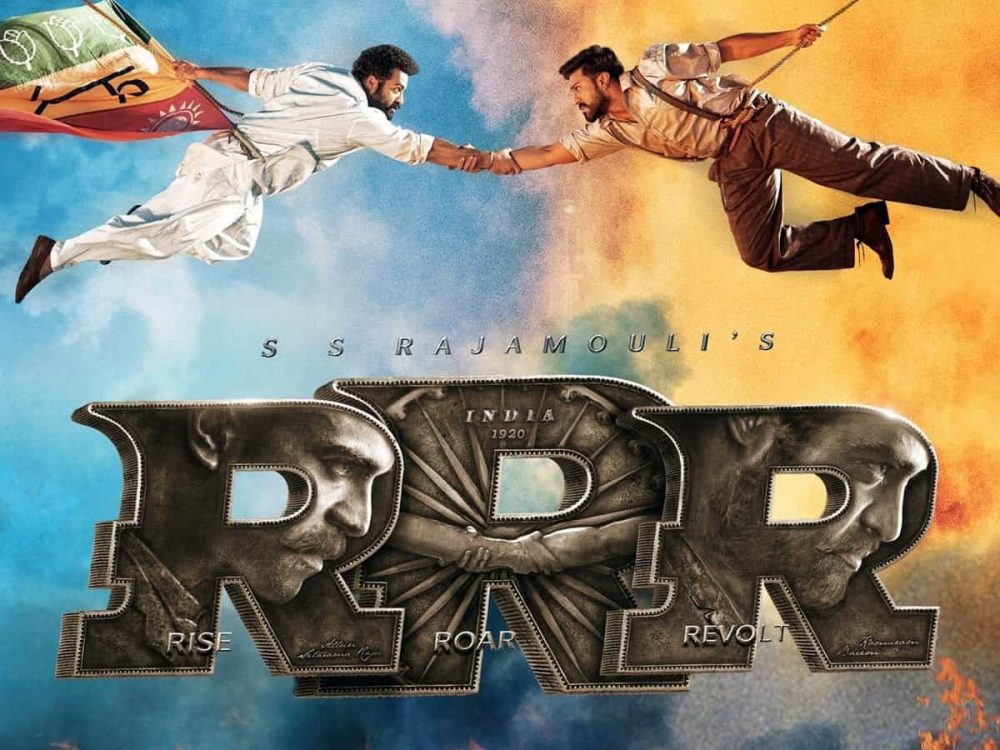

I found myself thinking about this once again Wednesday night when I saw the Indian action-musical RRR as part of a one-night-only “EncoRRRe” event in select theaters in the United States. You can watch it right now on Netflix, although for some reason they only have the Hindi dub (with subtitles available in other languages, including English), even though the actual film is primarily in Telugu. I don’t speak a word of either language, but that annoys me and I guess I’m the kind of annoying person who cares about stuff like that now.* Luckily, the EncoRRRe presentation was in Telugu, and since I heard such superlative things about how it’s the best action movie in years, I figured I’d treat myself to a ticket… with my mask on the whole time, of course.

(*Editor’s Note: It’s true. – JG)

Anyway, RRR (which stands for “Rise, Roar, Revolt” but has different meanings in other languages) is indeed a triumph, largely because of how gleefully it eschews subtlety. Granted, since I don’t speak Telugu, am not Indian, and had never even seen an Indian film before RRR, there’s no avoiding the fact that there had to be cultural references and other nuances that flew way over my head. I didn’t even know that its lead characters, Bheem (Nandamuri Taraka Rama Rao Jr.) and Ram (Ram Charan) were loosely based on real Indian historical figures until taking a Wikipedia dive on the subway ride home. But in terms of the core storytelling, dialogue, performances, aesthetics, et cetera, RRR is about as subtle as a tree branch to the face… something that happens to several characters throughout the movie.

Directed by S. S. Rajamouli, RRR is set in early 20th century India, right on the precipice of the nation’s revolution against British imperial rule. When British nobles trick a family from the Gond tribe into “selling” a little girl named Malli (Twinkle Sharma) to them as a slave, a small band of villagers – led by her superhero-like brother, Bheem – set out on a mission to save her. Meanwhile, the ruthless and ambitious Ram, who also possesses nigh-superhuman action movie abilities, is on his own quest to rise through the ranks as an Indian police officer serving British interests despite how this would appear to make him a traitor. Ram goes undercover as a revolutionary, and finds himself forging an apparently ill-fated friendship with Bheem.

I’m trying my best to make this as light on spoilers as possible, but RRR is so unsubtle that the film explicitly tells the audience what it’s about on several occasions. This is usually achieved musically, as the the songs function much like a Greek chorus. The lyrics wax poetic about the unlikelihood of Ram and Bheem’s friendship, the inevitability of betrayal, and even the fact that both these guys are fucking badasses. Surely most audiences could have figured all that out on their own, but the bluntness is exhilarating.

The thing you have to understand about RRR is that it goes hard. Bheem fights a wolf and a tiger with his bare hands in his introductory action sequence, and that’s not even the 10th coolest thing that happens in the film’s three-hour runtime (don’t let that intimidate you; the time flies by and I was still left wanting more). I’m not a massive fan of musicals, but a scene in which Bheem and Ram lead an intensely athletic dance-off against the British colonizers is one of the most exciting scenes I’ve seen on film in a long time. Subtlety can be interesting, but it’s rarely conducive to fist-pumping moments like that.

A lack of subtlety, however, doesn’t equate to a lack of nuance. That’s certainly true for RRR, but my go-to example for this thesis is Pixar’s Inside Out. It’s as unsubtle as a kids’ movie needs to be, but what’s impressed me about it most ever since I saw it in theaters in 2015 is the way that it uses simple symbols to illustrate something that’s actually quite complex: a child’s struggle to process her own emotions.

11-year-old Riley (voiced by Kaitlyn Dias) is the ostensible protagonist as she struggles to adjust to her new life in San Francisco following her family’s move from Minnesota. But most of the film literally takes place in her own mind, led by personifications of her own emotions: Joy (Amy Poehler), Sadness (Phyllis Smith), Fear (Bill Hader), Anger (Lewis Black), and Disgust (Mindy Kaling). It’s a deeply entertaining movie with some big laughs, but the highly literal depiction of the messy ways that human emotions interact with each other, especially in times of crisis, is genuine and thoughtful.

None of this is to say that subtlety is never good or necessary. One of my favorite films last year was Drive My Car, a subdued Japanese drama which won the Academy Award for Best International Feature Film. Directed by Ryusuke Hamaguchi and based on a short story by Haruki Murakami, its story of an actor (Hidetoshi Nishijima) coming to grips with the death of his wife while directing a stage production of Anton Chekhov‘s Uncle Vanya may not sound exciting enough to maintain your interest for the duration of its three-hour runtime. But while it may be slow, it’s never boring. The film is grounded and understated throughout, with characters rarely even raising their voices, but every shot, and every line of dialogue, is packed with layers of meaning. The subtlety is thrilling in the way it rewards a close viewing from a patient audience.

That’s great, I just want to challenge the snobs among us to consider that a story as subtly told as Drive My Car is just as valid as one as unsubtle as RRR. Some stories need to be told with a scalpel. Others are better suited for a chainsaw.

You (and the epic dance sequence) have sold me on watching RRR!

Comments are closed.