The Beat’s Greg-Gory Pall Thrillber is a connoisseur of the dark arts who has been accused of… several crimes against God and nature. Each week in Silber Bullets, he takes a terrifying look at the spookiest, scariest, and most blood-curdling bits of suspense and horror that he refuses to let out of his head.

Shortly after my horror kick began at the start of the pandemic, I made a point of addressing a major blind spot in my rediscovered identity as a horror aficionado: John Carpenter. I knew he was an influential filmmaker for a number of creators I enjoy, but somehow I’d gone 29 years without seeing a single one of his films. Streaming availability being what it is, I started with the first one I stumbled upon, albeit a sci-fi/action film rather than a horror film: 1981’s Escape From New York. It’s great for a number of reasons, including its distinct visual identity and a memorable starring performance by frequent Carpenter collaborator Kurt Russell as Snake Plissken, but what stuck with me most was the music.

I don’t know of many other directors who compose the music to their own films the way Carpenter does with his, albeit often with the help of collaborators like Alan Howarth in the case of Escape from New York. The only exceptions that come to mind are nu metal star Rob Zombie, whose horror-oriented directorial filmography includes a 2007 remake of Carpenter’s own Halloween, and Sorry to Bother You director Boots Riley, who until recently was best known as a rapper in hip hop band The Coup. Both Zombie and Riley were established musicians for many years before launching a film career, placing Carpenter in a unique position as a filmmaker first who also happens to make music.

That might lead you to assume Carpenter’s scores would be lacking, but that couldn’t be further from the truth. Carpenter’s minimalist, synthesizer-laden compositions, often with trace elements of rock and pop influence, brilliantly elevate the films they’re featured in and, in many cases, are quite listenable independent of the films for which they were recorded. Just listen to the funky drum and bass of Escape from New York‘s “The Duke Arrives,” which I do on a regular basis. It’s an appropriate tribute to funk legend Isaac Hayes who plays The Duke, and it also does a thrilling job combining catchy head-nodding rhythms with the film’s overall tense, oppressive atmosphere.

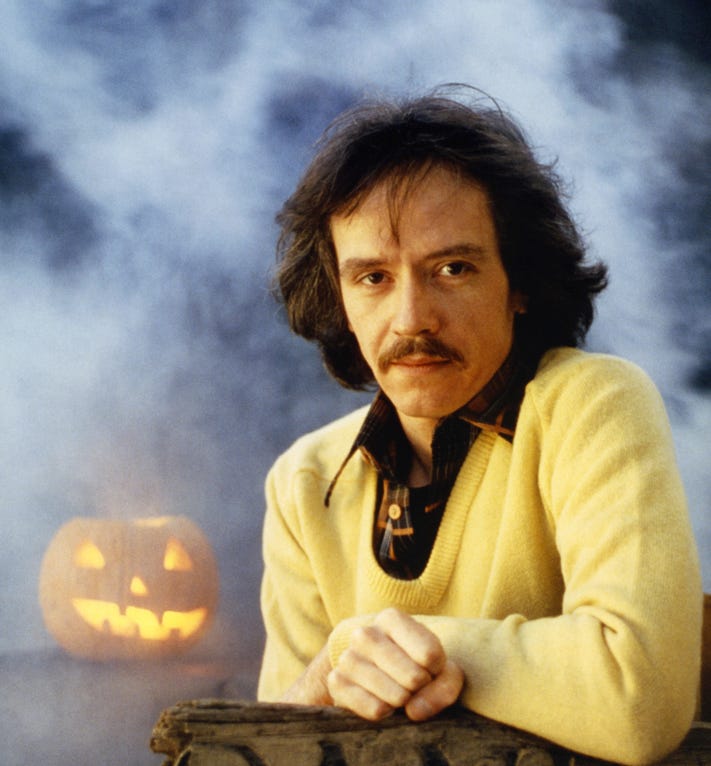

I next saw the original 1978 Halloween, for which Carpenter created not just one of the most iconic melodies in cinematic history, but what I’d wager may be the most iconic horror score of all time (at least if you don’t consider Jaws a horror film). It’s not just an earworm. Every time those menacing piano riffs play throughout Halloween – even when nothing ostensibly scary is happening onscreen – the audience gets the signal that something very much isn’t right in the fictional Chicago suburb of Haddonfield, Illinois.

Unlike most of the slasher films Halloween would influence, including its own sequels (Carpenter reluctantly wrote 1981’s Halloween II but never directed another film in the franchise), the first Halloween thrives on Carpenter’s restraint. Archetypal masked killer Michael Myers only commits four onscreen murders, and the violence that we do see lacks the blood and gore that would soon become a staple of the slasher subgenre. In between these attacks, Carpenter and company (including producer/co-screenwriter Debra Hill and Jamie Lee Curtis in her breakout starring role as pioneering “final girl” Laurie Strode) do an excellent job establishing the setting and creating a compelling cast of characters, but it’s that stuttering theme that keeps audiences on their toes and reminds them that nobody in Haddonfield is safe.

I’ve seen several other Carpenter films in the year since, including 1981’s The Fog, 1982’s The Thing (composed by the great Ennio Morricone), 1983’s Christine, 1987’s Prince of Darkness, 1988’s They Live (which might be my favorite of the bunch) , and even his 1993 horror-comedy anthology-style television movie co-directed with Tobe Hooper, Body Bags. As with any creator I love, I enjoy some of these films more than others, but the prominence of Carpenter’s scores are a key factor in their entertainment value.

For example, Christine is good fun, a zippy B-grade Stephen King adaptation about an evil car, but as much as I like the old time rock and roll that dominates the soundtrack, its prominence means there’s disappointingly little in the way of Carpenter’s signature synthesizer sounds.

Somewhat conversely, Body Bags is my least favorite of the Carpenter films I’ve seen. I avoid body horror as a general rule, and the TV-quality production value lends to the feeling that it was a half-hearted affair. That’s not entirely the filmmakers’ fault: originally it was meant to be a Tales from the Crypt-esque series on Showtime, but the network pulled funding to force Carpenter and Hooper to reduce it to a single film midway through filming. Carpenter’s films often have small budgets, but Body Bags is the only one I’ve seen that feels cheap. Still, the playfully spooky score makes it feel like a genuine Carpenter affair. He even appears onscreen as a disgusting, sardonic coroner, alongside a slew of cameos you’ll get a kick out of if you’re into the same stuff I am, including Wes Craven, Sam Raimi, Mark Hamill, Roger Corman, and even rock goddess Debbie Harry of Blondie.

Martin Scorcese once wrote that “John Carpenter is a filmmaker who is unashamed to stay within the genres he loves (horror and science fiction) and who practices his trade like a master craftsman. His pictures always have a handmade quality—every cut, every move, every choice of framing and camera movement, not to mention every note of music (he composes his own scores) feels like it has been composed or placed by the filmmaker himself.” It’s that “handmade” quality that I’ve come to love most about Carpenter’s films, and why I so appreciate his scores especially.

It’s not that I necessarily believe in auteur theory when it comes to cinema, but that I appreciate the sense in which Carpenter seems to involve himself in virtually every stage of the filmmaking process. Carpenter’s films are obviously aided by a number of talented collaborators, including other composers. In recent years, his son Cody Carpenter and godson Daniel Davies (son of The Kinks’ lead guitarist Dave Davies) have joined him on the musical front, and the trio worked together to compose the score for the 2018 Halloween sequel, confusingly also called Halloween, as well as its 2021 sequel, Halloween Kills. But what I’m more interested in only has a tenuous connection to film.

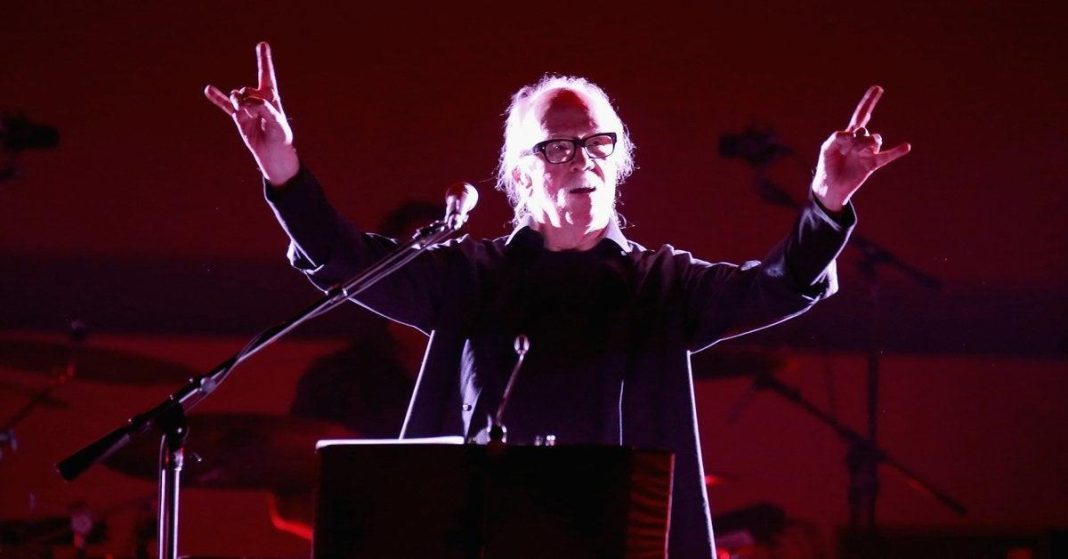

Lost Themes is the debut studio album by John Carpenter, with help from Cody Carpenter and Daniel Davies. Released in 2015, it was followed by Lost Themes II in 2016 and Lost Themes III: Alive After Death in 2021. All three albums are well worth listening to, and while there’s an obvious appeal for fans of Carpenter’s filmography, I’d encourage anyone with an appreciation for electronic music to give these songs a fair shake.

I’m a big fan of synthpop, from classic bands like Depeche Mode and New Order to contemporary artists like M83 and The Midnight. While Carpenter is hardly a pop artist, I suspect he had a far bigger hand in bringing synths to the mainstream than he gets credit for. Today, you can hear Carpenter’s influence in 80s nostalgia-fests like Stranger Things, and in the music of my favorite synthpop band, CHVRCHES, whose latest album, the horror-inspired Screen Violence, has Carpenter’s sonic fingertips all over it.

It’s because of the enormity of Carpenter’s influence, as well as the high quality of the albums themselves, that I actually kind of hate “Lost Themes” as a title. I’m reminded of something Prince once said about how he disliked when people referred to his music as “experimental,” as it suggests the work is “unfinished.” On that same token, “Lost Themes” suggests these songs are something of an accident, as if they were intended for films Carpenter never got to make, or that they were simply misplaced at some point. It does a disservice to his own craftsmanship and originality when the title implies, even unintentionally, that these songs are missing a visual component. This is fully-realized electronic music that deserves to be appreciated on its own merits.

Of course, that’s not to say we should reject the temptation to ascribe narrative onto songs with titles like “Distant Dream” and “Dripping Blood.” One of the great things about music – and why I don’t habitually watch music videos – is that it allows us to play out a story in our own heads. This is especially true of instrumental music, where the specific dialogue and characters, as it were, is up to the listeners to imagine.

Theoretically, one could listen to the They Live soundtrack without knowing it was written for a film, and imagine a totally different story playing out in their heads. Perhaps they’d imagine it’s about a hard-boiled 1940s private eye, or a sexy rendezvous between two rival spies. But the fact remains that They Live is a movie that exists, and the music was written to accompany the tale of a drifter (Roddy Piper) who discovers a pair of mysterious sunglasses which reveal that the world is secretly run by a cabal of evil space aliens seeking to enslave humanity with the power of, well, capitalism. If you played this music for a stranger and asked them to tell you what they imagined, they’d be wrong if they didn’t describe this exact thing.

But the magic of each Lost Themes song is the lack of baggage. What’s “Weeping Ghost” about? Who is this ghost? Why are they weeping? Are they a scary ghost, or a friendly ghost like Caspar? There’s no wrong answer, and if you didn’t know the title, that opens up a whole other world of narrative possibilities.

Because Carpenter’s most impactful films came out in the era that they did, as well as the slew of imitators, I think there’s a tendency today to think of the synthy sounds he pioneered as cheesy or antiquated. But actually watching the films in their proper context reveals their dark edge and ingenious intentionality. When you listen to Carpenter’s non-filmic albums, it becomes ever more clear that his ear for evocative, thrilling electronic music can still sound as vital as any of the themes he wrote at the height of his success… and as exciting as any younger, contemporary musician.