The fastest man alive is about to encounter something he’s never faced before: pure cosmic horror. DC’s new The Flash ongoing series, part of the Dawn of DC initiative, comes from writer Si Spurrier, artist Mike Deodato Jr., colorist Trish Mulvihill, and letterer Hassan Otsmane-Elhaou. It follows Wally West, his wife, Linda Park-West, and their kids – Iris, Jai, and new addition Wade – along with the extended Flash Family of DCU speedsters as they face new threats, powered-up old enemies, and a Speed Force – the familiar source of all of their powers – that’s become increasingly erratic.

Joe Grunenwald: Tell me a little about your history with The Flash. When did you first get into the character? Have you always wanted to write The Flash?

Si Spurrier: I mean, I’m not gonna lie, it’s sort of a late-flourishing interest. I was always vaguely aware of the character, but coming from here in the UK, it was always sort of sci-fi, spooky, strange genre stuff before it was the superhero stuff. And then it’s when you started to see writers whose names I would have recognized, like [Mark] Millar and [Grant] Morrison, and all of those guys sort of drift across to doing those things – that’s when I started to pay attention. That’s probably the beginning of it. I mean, they didn’t do it for long, about a year, but those few issues are so packed with the sort of 2000 AD-ish energy that I recognize from my own comics vernacular that it just made me aware of how much potential this particular corner of the DC universe could have.

It’s the sort of IP, for a host of reasons that I could bore you with, like pub chat territory, but it’s the sort of IP where it doesn’t feel awkward to be telling very intimate human stories in the same breath as gorillas invading Central City, or just really batshit sci-fi stuff. As long as you pack it with clever ideas, and as long as the underlying theme speaks to humanity and heart and doing the best you can, and it doesn’t matter how fast you can run, you also have to be a good person – these are all sort of things that The Flash is so very good at. So it’s always been a sort of paperclip at the back of my head that if ever I got the chance, those are the sorts of things that I could throw at it. I’ve never had a hard time generating ideas – if anything, one of the criticisms I get is that I try to fit too many ideas into a single page of comics, and I think that’s bollocks. I think there should never be too many ideas. But that appears to be okay in The Flash. I can get away with it. Nobody goes, ‘Hang on a minute, you’ve had too many ideas, calm down and chill out a bit.’ So yeah, it seems to fit.

Grunenwald: You mentioned the Morrison and Millar stuff. And I know you’re taking a cosmic horror approach to this book. I feel like there are sort of elements of that in those stories, too. Like, Wally breaks both of his legs in Morrison’s first issue. And then the last arc with the Black Flash, where he’s sort of being haunted by just the specter of death. How did you land on that as your approach? Was it inspired by that vibe? Or are you bringing something different to it?

Spurrier: That’s a good question. Honestly, when the opportunity arose to pitch, the question was, ‘What would you do if you were writing The Flash?’ And it was a no-brainer. That always confuses people when I say that, as if it’s not obvious that The Flash and cosmic horror should go hand-in-hand? And it confuses me a little bit, because for me it’s so completely obvious. Of course they go together, why wouldn’t they? So I don’t know exactly where that came from.

Grunenwald: I mean, you sort of said yourself, The Flash has always been sort of grounded in the humanity of whoever’s in the suit.

Spurrier: I guess. Cosmic horror at its best is about making the human feel simultaneously small and special, because they are adrift in a vast and careless universe. That’s the sort of Lovecraftian approach. When I came aboard The Flash, I was inheriting the incredible work Jeremy [Adams] had been doing – and for those who haven’t read it, they should, it’s just the most perfect, quintessential version of heart-filled superhero comics that I can think of. As a result of its brilliance, I’ve inherited this extremely stable, very happy, human picture of a man surrounded by people who love him doing the best you can, and that’s wonderful. You can’t sustain that without drama, but it was important that I not just flip the table and say, ‘Fuck all that stuff, we’re going over here now, none of that matters.’ So there was an importance that whatever direction I took, it would need to be respectful, it would need to allow me to still play with the toys that feel so essential to The Flash IP, like the big ideas, the sort of Silver Age energy, gorillas dropping out of the sky, all of that stuff, but also permitted me to pivot towards territory [where] you can have something quite important to say.

And the last element is The Speed Force, which, from the beginning of my awareness of The Flash has always been like a little red flag in my head. Because it’s a mystery. Multiple times, writers have attempted to have authoritative, science-y people pop up in the comic and say, ‘Okay, we know what the Speed Force is, and it’s this.’ And then two weeks later, somebody says, ‘Okay, we know what the Speed Force is,’ and they never match up, and a lot of them make zero sense. What’s really fascinating about this whole paradigm is that, you’ve got all these characters who are whizzing around, tapping into this energy every day, and using it for, mostly, really selfless, amazing things, using it to be good people, to save the world, to help people, to do the right thing, and yet, none of them has a fucking clue where it’s coming from, what it is, whether there are consequences every time they tap into it. And that’s fascinating. And [chuckles] it’s very American, you know what I mean?

Grunenwald: [Laughs]

Spurrier: Forgive me for being that crude, but the kind of formative image I have in my mind is an oil prospector striding across the frontier, and he’s like, ‘I’m gonna save this country, and everybody’s gonna get rich, and we’re all going to have cars, and 100 years of progress, it’s going to be great.’ And then cut to now and everything’s on fire, and we’re all getting lung cancer. I’m not saying that’s what’s happening with The Speed Force, it’s not, it’s something a little bit more interesting than that, but it speaks to that pioneering idea of, ‘I will do what I feel is right now, even though I don’t understand why.’ And there’s something that lends itself extremely well, when you think of it in those terms, to unforeseen consequences, and things that come down the same pipe that aren’t necessarily to do with The Speed Force, [and] things that are to do with The Speed Force. So I’ve got all of these huge conceptual mysteries to toy with, and I’ve got two or three really big answers that I’m gonna enjoy taking quite a long time to get to, and between now and then just a huge amount of beautiful, intimate human drama, and big, crazy, Silver Age-vibe action, and that’s the prescription.

Grunenwald: I sort of hear this a little bit in what you’re saying about The Speed Force, and on social media you’ve likened this book to Immortal Hulk and Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing. I feel like those are books that have sort of a, ‘Everything you know about BLANK is wrong’ vibe to them. Is that sort of how you’re approaching The Speed Force here? Or can you just elaborate on that a little bit more?

Spurrier: Yeah, no, you’re not a million miles away. I always use those [stories] as sort of comparative touchstones because of what you’re describing, rather than because I pretend that I’m writing an issue as good as “The Anatomy Lesson.” I would love to be compared to those things in the same breath, but that’s not because I claim that level of brilliance. But no, it’s about taking something that everybody has just started taking for granted and then saying, ‘Have you ever really thought about this?’ Because when you actually think about it, it’s a bit weird, isn’t it? It’s a bit odd, and maybe it’s not quite what you thought it was. And what I love about The Speed Force, and we make a lot of this as we go through – sidebar slightly, we have this amazing character, Michael Holt, Mr. Terrific, who’s one of our cast members, he’s an unbelievably clever man, who is simultaneously Wally West’s kind of science guy, who’s quite handy for the sort of Basil Exposition stuff, but is also his boss, and that’s a dynamic that doesn’t exist anywhere else in comics. It’s really, really clever. So we’ve got that going on, and Michael talks about the fact that, if he didn’t know better, he would think The Speed Force was being deliberately contrary, because every time he studies it, and he thinks he’s close to figuring out the fundamental math that sits behind it, it stops working and he has to start again.

Now, what that actually tells anybody who knows anything about quantum mechanics is that this is clearly a quantum phenomenon. Every time you try to observe it, the whole waveform collapses, and it starts to be something different. We toy with that relentlessly over the first arc in a way that I hope isn’t too techno-wanky and gibberishy, and it leads to some quite interesting places. And most importantly, it opens the door to some really interesting outside agencies coming in and sort of exploiting this gap in the knowledge. That’s kind of where we’re heading, the fact that The Flash Family have to admit they don’t quite know what they’ve been toying with all this time, and that they are therefore perhaps not as equipped to deal with certain things as they would like. To say more than that would be to spoil a lot, but as you can see, there’s a lot of very fertile soil here.

Grunenwald: The outside agencies that you mentioned – again, probably you can’t go into too much detail without spoilers, but, you know, Amanda Waller is playing a big part in the whole Dawn of DC story arc. How closely does this tie to the overall Dawn of DC initiative?

Spurrier: Relatively closely. I’m keen that the core thing is a very speedster-centric thing, and it cracks open avenues that are on an order of magnitude bigger than the biggest thing that matters on the planet Earth. So there’s that. On the other hand, it’s also a very intimate story about a family who happen to be superheroes, some of them. So a lot of that realpolitik that’s going on on the ground in the DC Universe is very pertinent and absolutely plays a part. To give you an example, we’re participating quite strongly in the Beast World event that was announced recently, where we’re doing some really clever stuff in there, which is going to make it part of my ongoing arc rather than it just being a sort of sideways look at stuff, which I feel quite good about. I’m always a bit concerned about these sorts of tie-in events feeling a little bit disposable, whereas, frankly, I have so little real estate to toy with all my ideas that when somebody comes along and says, ‘Hey, do you want 40 pages to do a thing?’ I’m like, ‘Yes.’ And it’s going in my collected book, and it’s going to be part of the stuff, ao it all works really nicely for me. I hope that answers your question.

Grunenwald: Absolutely. Yeah. I still just want to talk about The Speed Force. You’ve got Maxine Baker, Animal Man’s daughter, as part of your supporting cast as friends with Iris and Jai. So that leads me to thinking about The Red, and The Green from Swamp Thing, and, like, elemental forces, and how the Speed Force is sort of similar to that…

Spurrier: You’re fishing for answers you’re not gonna get at. [laughs]

Grunenwald: [laughs] Fair enough.

Spurrier: But you’re thinking at that level of, let’s think about it all in a different way. Let’s not set ourselves any limits, let’s not say we have to understand an equation that makes sense. Let’s start thinking about this in really big terms. That’s exactly the line that I went down when I first approached this problem.

Grunenwald: Gotcha. So I want to step back from that a little bit and look at Wally and his family. The relationship between Wally and Linda is important to a lot of people, myself included, and then you’ve got Iris and Jai who’ve been really built up as sort of co-leads in the previous run. How do the three of them fit into this cosmic horror story that you’re telling?

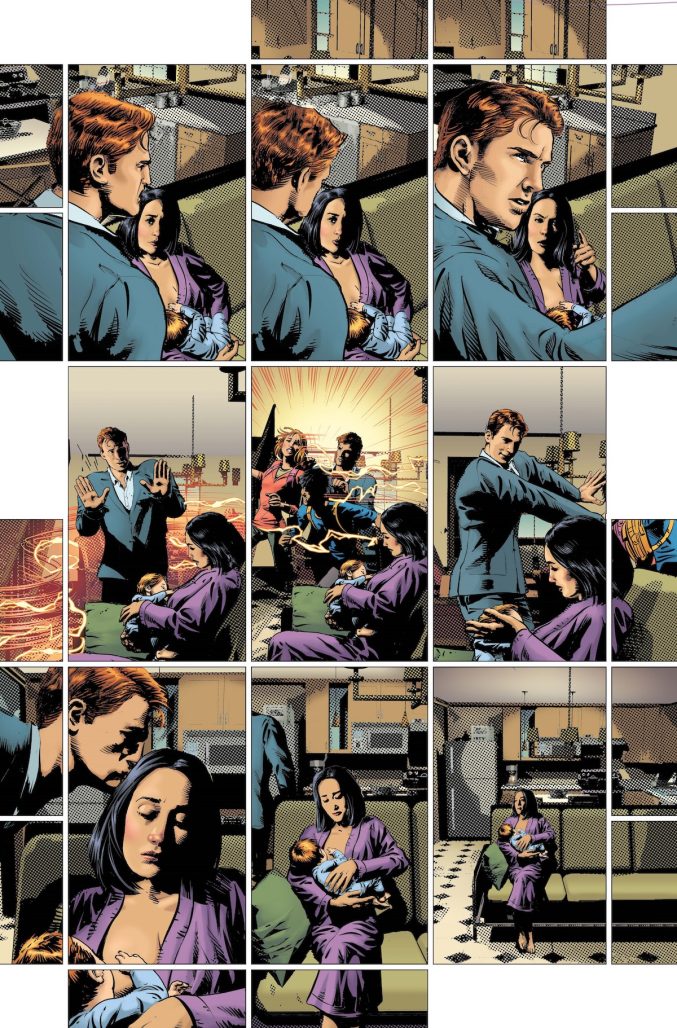

Spurrier: They’re key. As we’ll see in issue one, the dynamic I’m playing with is to come in, to see this family at its best, to see Wally as this guy with 1000 hats who’s trying to be everything to everybody, spinning all of these plates, and then one by one, we sort of check in on them and look a little bit closer and realize that, because it’s impossible for anybody to be everything to everyone all the time, cracks are starting to show. Not because there’s a lack of love, not because anybody’s changed their mind, not because Linda’s sitting there going, ‘I don’t love him anymore,’ it’s none of that. That would be cheap. It’s that there are strains and stresses put onto any family, any human from the outside, and that’s what’s crushing them. That’s what slowly making Wally’s smile start to falter.

In Linda’s case, the catalyst for the things that are going to happen is that, while she was pregnant [with new baby Wade], she had this very brief taste of occupying the same kind of heightened world that the rest of her family do. She was able to utilize superpowers, she could save the world, she could write five novels in a day. And then she has her baby boy who was kind of lending her his powers, and suddenly, she’s back to being merely an incredible journalist, ridiculously capable woman and all-around incredible person, and it feels like going back to nothing. She’s going to mourn that loss. And she still lives in a house where all the rest of her family are constantly whizzing around like mosquitoes, and she feels so lonely, and so guilty for feeling that way, because she knows all these people are just doing what feels right to them. That kind of triggers her emotional story. Jai and Irey have their own versions of that. And I’m not even going to touch on them right now, because issue four is all from Irey’s perspective, and that’s really interesting. Issue five is all from Jai’s perspective.

It’s that sort of book, where Wally can be our central character who is the sort of beating heart of all of these different threads, everybody interweaves through his story, and yet, he’s not the story all the time. We can jump away and check in with somebody else, witness all these different threads through somebody else’s eyes. As a writer who gets bored very quickly, it’s such a privilege to be able to utilize all these different voices. You can see it in issue one, we change the tone and the timbre of the voice every few pages. I think it’s to the book’s credit that you can do that. It feels a little bit like a team book without being a team book, if you know what I mean. It can be very intimate at the same time as having lots of different story threads running in parallel.

Grunenwald: Talk about working with Mike Deodato and the rest of the creative team. What are they bringing to this book that you didn’t expect?

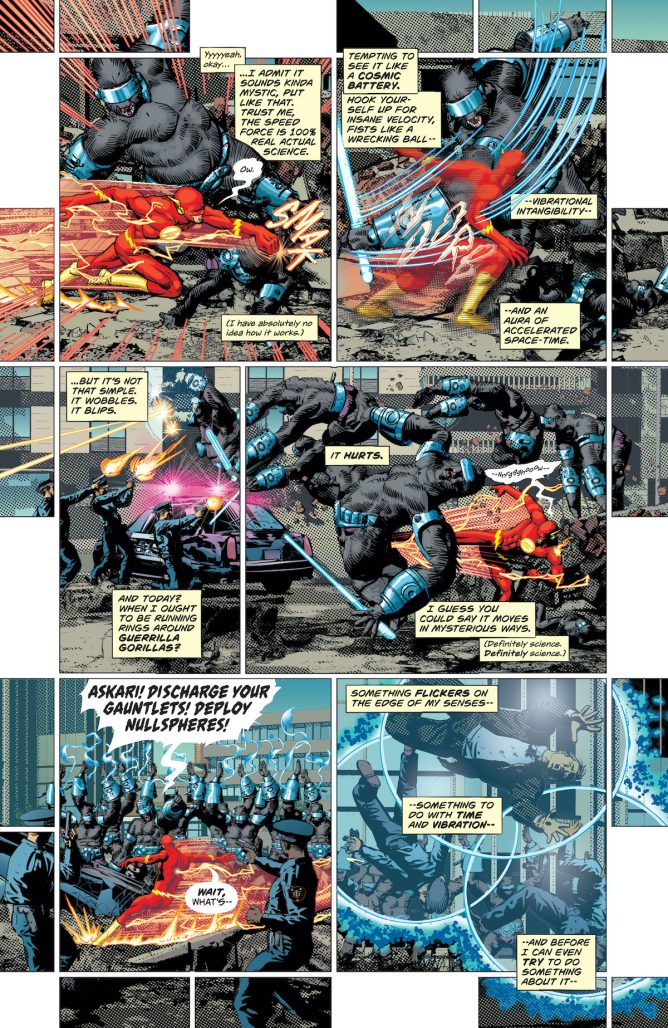

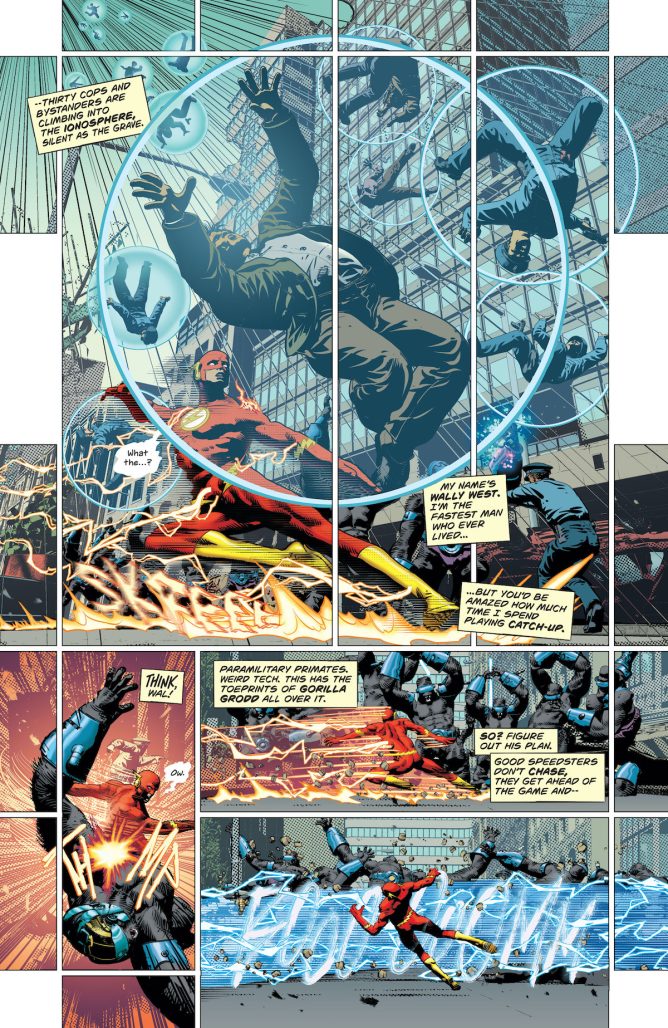

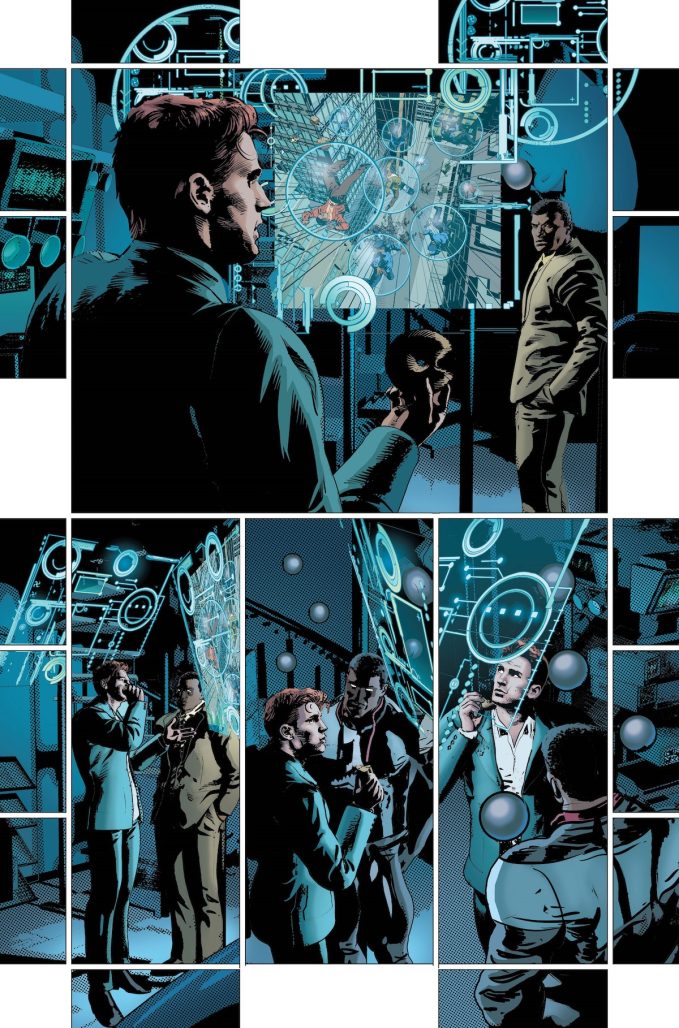

Spurrier: What’s great about working with Mike is that I got exactly what I expected, which is an absolute legend. I sincerely doubt I would have been given permission to take a book of this caliber and size off in the direction I’m taking it if it wasn’t backed up by somebody of his stature. He draws anything, and I mean anything, with the same professional, ‘Yeah, I’ll give it a go’ sort of shrug of the consummate draftsman. He can go from gorillas being knocked out in the streets to a mother feeling lonely to a kid locked in a boiler room to an alien dimension, and then back to a superheroes laboratory, all in the space of a few pages, and it doesn’t feel crazy, it doesn’t feel stupid. It doesn’t feel like we’re utilizing different voices and tones.

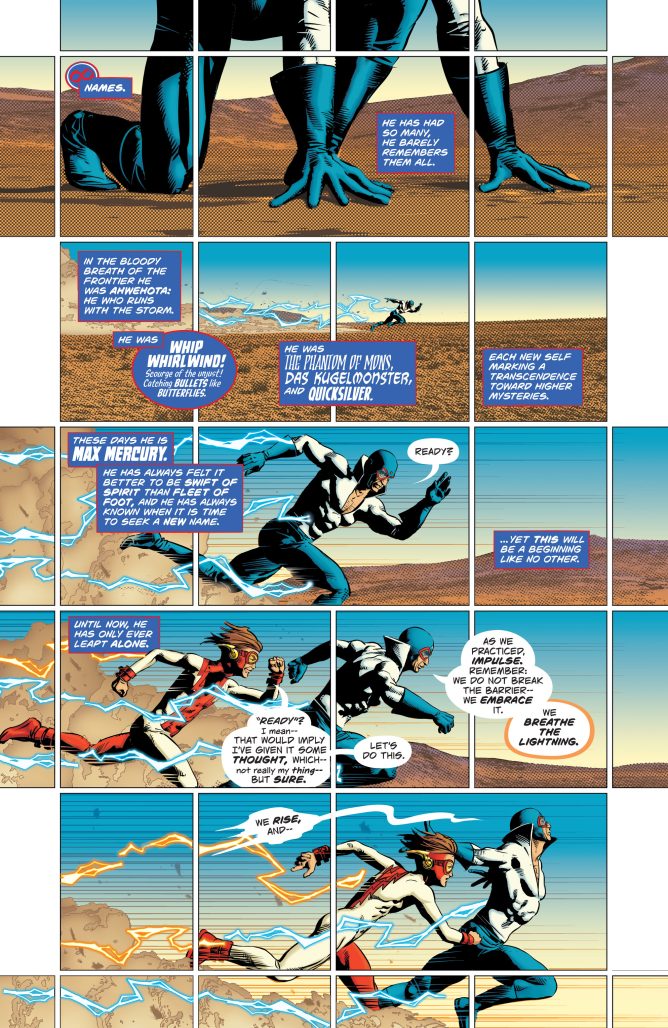

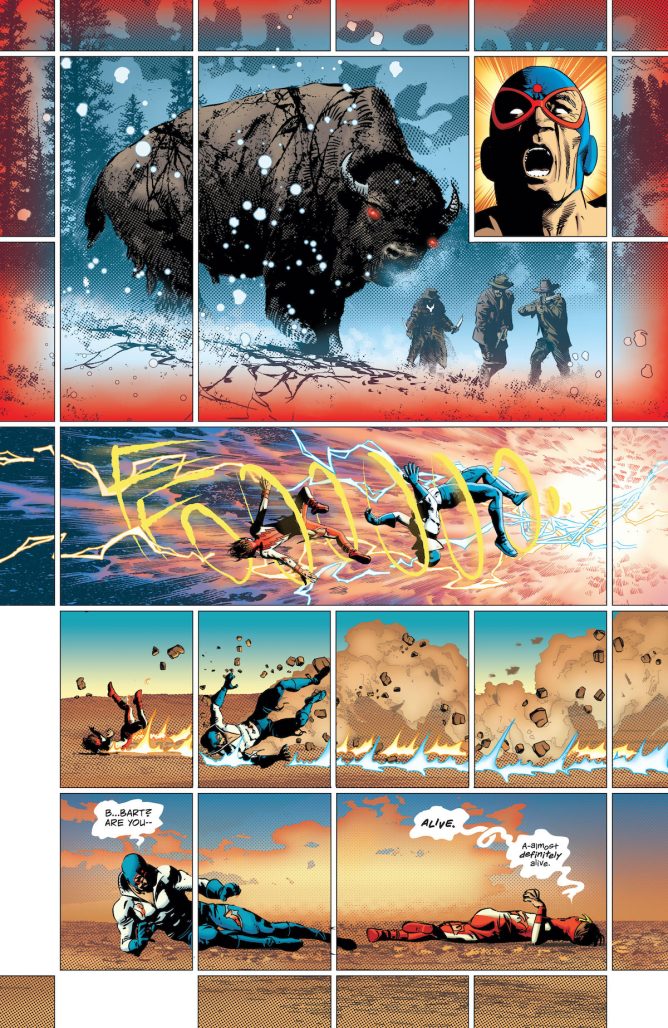

He’s got that simplified primary, utterly perfect draftsman’s line that works so well for classic superhero comics, but always underscored by just a smidgen of sinister, shadowy spookyness, which makes him such a great choice for the tone we’re gradually steering towards. And then there’s his, he calls them Mondrian Lines, quite appropriately. He breaks up panels into sub panels in a way that I’ve never seen anybody else do. And that allows me, and Hass especially, our letterer, who’s like just wildly inventive, and utilizes text in a way that I think it should be used in comics, which is as a graphical interface, it’s something that makes you respond, you should feel things when you read words, rather than just having to utilize it like blank text. And he can play with Mike’s panel structures in a way that tells you things about whether a character is entering a scene or leaving it, whether he’s in the room or not in it, he can break up beats.

Basically, we have a lot of back and forth when the pages come in about, ‘Can we break this balloon up and put half of it in that panel.’ And that conversation makes this book feel, I think, like no other book on the stands. It feels simultaneously very dense, but very breathless and fast. And I think there’s a sort of really beautiful alchemy in the team that we’re absolutely learning on the job. This has never been done quite this way before, and we make mistakes, but we’re learning how to make it all fit together. There’s a scene that feels very slow, and a scene that feels very fast, and it’s just wonderful at this stage of my career, having been doing this for quite a while, to suddenly stumble upon all these new tools that can be toyed with in different ways. It’s quite a privilege.

Grunenwald: Is there anything else that you want to tease about what’s coming up? I know you’ve teased a lot already. But is there anything that you’re excited for people to see?

Spurrier: There’s a lot of good stuff. I could waffle on, and as you know I’m a waffler. There’s a beat at the end of issue two, the last page of issue two, which I think is going to lift a lot of eyebrows, and make a lot of people who might have given this book short shrift a second look at it, and we’ll hopefully set a quite interesting standard for where we go after that and open up some opportunities and possibilities that people probably didn’t realize we had to play with.

Grunenwald: Interesting.

Spurrier: [laughs] It’s very mysterious, isn’t it?

Grunenwald: Very mysterious. I’m excited to see your take on The Folded Man, who I think has maybe appeared three or four times before and I always thought was a really cool visual character.

Spurrier: He’s amazing. And that’s, without going back into it, that’s the sort of thing that made me think, ‘Well, of course The Flash is a horror story.’ Because like Mirror Master, Folded Man, [there’s] all these characters who are either bizarre, impossible science and a bit hokey, or they have a sinister edge that makes you shiver because nobody can possibly understand how they do what they do. And it’s that. It’s got to be that.

The Flash #1 is out in stores and digitally today.