People never know what they sign up for with the panels they attend at Comic-Con. Some panels regurgitate mind-numbingly boring content. Some panelists lack chemistry or enthusiasm, producing much pain and little gain in the hour that stretches painfully to infinity. Then there are those who bring infectious chemistry, enthusiasm, and comedic gravitas to the plate. At San Diego Comic-Con on July 27, 2024, “Inheritance and Legacy: Nonfiction Comics” checked off all those boxes as the smattering of attendees were treated to a conversational hour of camaraderie, community, and culture.

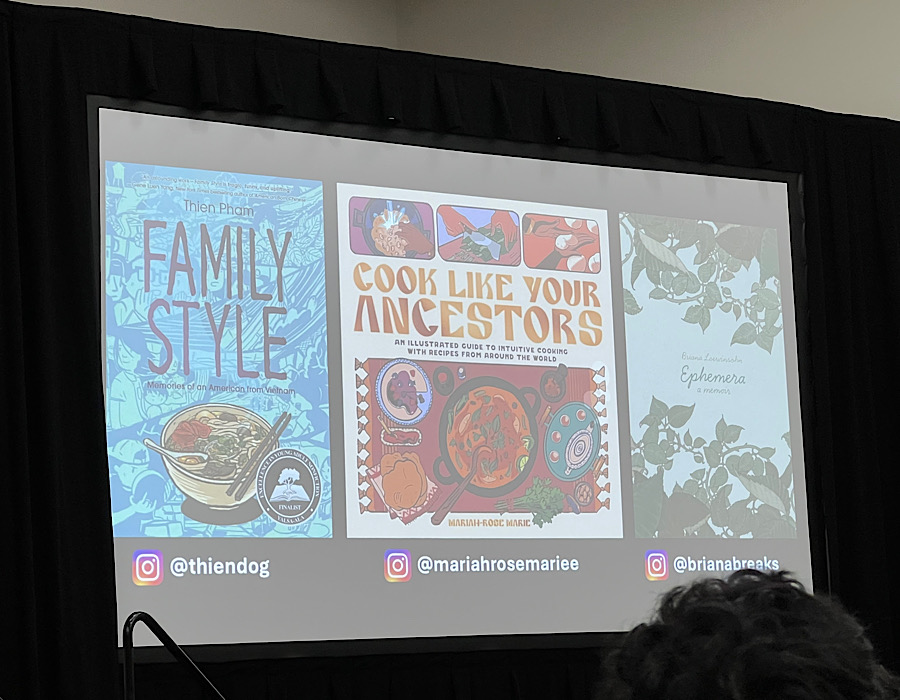

Gene Luen Yang (Lunar New Year Love Story) moderated an entertaining panel that included pals Briana Loewinsohn (Ephemera), newly crowned Eisner Award winner Thien Pham (Family Style: Memories of an American from Vietnam), and new kid on the block, Mariah-Rose Marie (Cook Like Your Ancestors: An Illustrated Guide to Intuitive Cooking with Recipes from Around the World). Yang dubbed Loewinsohn’s book as “astounding,” Marie’s book as “compelling,” and much to the exaggerated chagrin of Pham, who thought “delicious” a letdown to the glowing praise his fellow panelists received.

Yang asked the panelists to address a common theme across the three books—the people (family) who came before them and the reactions these stories had on their relationships.

Marie, whose book collects recipes from around the world and codifies ancestral cooking recipes that current generations can replicate, spoke to the fear of taking these classic recipes and tweaking the ingredients to appeal to modern tastes. One example Marie discussed was for a veganized version of pho ga, or chicken pho. The friend who provided this recipe was a home chef who had published the recipe. Marie sought validation from the friend’s mother, who broke into tears.

“Her response was indicative of the rest. ‘I really appreciate what you have to say about the recipe and the history of the recipe, and specifically, the fact that she said this was from her own materials, but the recipe was similar.’ As long as people feel respected and represented,” said Marie.

Pham was determined to hate that pho ga recipe without chicken since “there’s no chicken in the chicken,” but to his surprise and astonishment, he ended up loving the recipe, as did his mother, who privately quipped that Pham might need to reconsider his unhealthy meat-devouring lifestyle given advancing age.

Despite Pham’s success as a cartoonist, his parents insisted that he maintain a day job, even if they thought he was the best cartoonist on earth. But Pham’s mother was a little less enthused about his idea for a sequel.

“I had this idea for the sequel. I go back to Vietnam, and it’s like the opposite of Family Style, where instead of coming from Vietnam to America, I go back to Vietnam to experience the food, the culture,” said Pham. “I was telling my mom this, and she’s like, ‘I can’t wait,’ and next thing I know, they’re planning an entire family trip!

The thing that made me want to go back to Vietnam was that my mom told me that we still own that house that I grew up in before we came to America. That inspired me, and I was like, I need to go there, see where I grew up. And then before we got a chance to go back, it was COVID time, and my grandma, unfortunately, passed. away. Now, I love my grandma. I was very sad she passed away. She was 98. However, I was like, I want to go back to Vietnam to spread my grandma’s ashes. This is going to sell some books. So, I took this to my mom, but my mom was like, nobody wants that. We don’t do that; these people don’t scatter ashes. But yeah, my family is over the moon and very excited about this book.”

Like Pham, Loewinsohn’s parents supported her artistic ambitions but happy that she maintained a day job, “which is teaching comics with these jokers.” Loewinsohn’s work, however, is colored by her mother’s mental illness.

“If you’ve ever dealt with someone with mental illness, it can be a very complicated relationship or sometimes it’s like the most love and sometimes it’s your biggest monster all in one person. I could have never written the story before she passed away because I would have been too scared of what she thought of it. But since she was gone, I felt really compelled to write a story about us. And I try and try to get time to draw her. Every time I drew her likeness, I almost felt like sick to my stomach because she was such a scary person.

And then what I did for Ephemera was I took it completely out of reality. It doesn’t look like me. It doesn’t look like where I lived. All I tried to do, as honestly as I could tell, were feelings of what it felt like to have her as a mother, and there are very few words. If you notice, the words are actually all directed towards her, so I’m speaking to her in the book, trying to almost commune with her. And I tried to really honestly to find how I felt settled at the end of the book, with wrestling with these two very strong feelings that I have towards her. So, I’m hoping that her ghosts that follow me around would be happy with the book.”

Yang drew significant conclusions from each of these stories, which highlights community over individualism, a departure from the overarching theme of comics where an individual finds their power and makes their way in the world.

“That’s a really good question,” said Pham a little sarcastically. “Like, I’m really impressed by that.”

And then in answer, Pham explained his need to always look for community in high school and during his quest to create comics. Pham found that community in Yang, Loewinsohn, Jason Shiga and Derek Kirk Kim. Community provided Pham with the inspiration and support to write Family Style.

“I reread the book, and I realized that every step, every chapter, not only does it deal with a food and a certain thing. Every chapter has a different community that I was involved in. I didn’t realize what I was trying to put it until, ‘Oh, my! I’ve been needing this all my life,” said Pham.

“When you are a refugee, and you’re in a refugee camp, you need that community. When you come to America, you go to a community you need. When we first came here, we were latchkey kids. In kindergarten, my brother and I were left alone at home from after school until like eight o’clock at night. So that community was the thing that kept us alive, that somebody who wasn’t working at that time to check in on us and then when my parents got home, they would check with all the other kids. So, we needed that community when I was growing up. That’s why I always need that community. I just feel safer. I feel happier when people are around me. I’m a super extrovert. I need that energy.”

Marie, who did not have a relationship with her parents, found the process of collecting recipes soothing.

“I wanted this book to be a total invitation that you can build your own connection to a place, a way for me to tell them something,” said Marie.

Loewinsohn’s search for community arose from different circumstances. Being left to her own devices much of her childhood, where family was “all just living parallel lives in spaces,” Loewinsohn spent a lot of time alone, developing her art. Art led to connection with the comics community. And that was the community that stuck with her.

The conversation then turned towards the use of metaphors, such as gardening (Loewinsohn) and food (Marie, Pham), as stand-ins for human relationships. Loewinsohn stressed the importance of making art that one loves, and plants represent life. She described her attempt to create an atmosphere similar to the dramatic opening in the film adaptation of Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca.

“It [the film] starts with the narrator saying ‘Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again,’ and then this house opens a gate, and it’s this fog going through these gardens. That is to me what Ephemera is. It’s like you’re going into the body of memory. And I feel like plants are like that, too. So, we’re using plants to say my mom didn’t give me enough affection. And then you would see that those two things juxtaposed together was much more interesting than just watching straight images.”

Pham used food as a stand-in for human emotions simply because emotions are harder to write about than food.

“I’m like a man child and so I can’t really process connections articulately,” said Pham. “I have to deal with metaphors, so is like that. Even though it’s a food, that is what happens in that chapter. I have a chapter about assimilating to American life as a kid coming from Vietnam. So, I chose to talk about my experience with Salisbury steak. When we first came to America, I went to school, we had the free lunch program, and that was the only thing we ate most of the time. When we first ate Salisbury steak, I was like, this is disgusting. And then eventually, I loved Salisbury steak. That was my metaphor for becoming American.”

Finally, the trio discussed upcoming projects, with Loewinsohn anticipating an early 2o25 release of Raised by Ghosts and Marie’s children’s book that Random House will publish in 2027. Pham will illustrate a graphic novel about chess that will be authored by Steve Sheinkin. But then, Pham teased a new project that drew applause from the audience but disbelief from Yang.

“You ready for this? Thien Pham, Gene Yang and Briana Loewinsohn are going to be doing book together.”

“No! Dude, you were like, let’s think about it,” protested Yang. “It’s not something we want to announce on a panel!”

And thus concluded the panel of the Three Amigos, where old-fashioned ribbing, offbeat humor and camaraderie combined for an engaging hour of respite from the madness of Comic Con.

Stay tuned for more SDCC ’24 coverage from The Beat.