Some artists can’t help but document the things everyone else has forgotten. Drew Friedman has spent four decades doing exactly that—drawing incredibly detailed portraits of Borscht Belt comedians, character actors you’d recognize but couldn’t name, and the kind of showbiz lifers who never quite made it big. Kevin Dougherty‘s documentary Drew Friedman: Vermeer of the Borscht Belt (SHOUT! Studios) doesn’t just profile this singular artist; it asks a bigger question: why do certain creators feel compelled to rescue the overlooked from complete cultural oblivion?

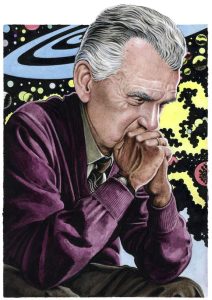

Friedman’s technique—painstaking stipple work that builds hyperrealistic portraits through thousands of tiny dots—becomes something of a visual metaphor here. Each dot is an act of preservation, a refusal to let these faces disappear entirely. Dougherty mirrors this obsessive attention by assembling an impressive lineup of interview subjects: the late Gilbert Gottfried, Patton Oswalt, Marc Maron, Richard Kind, Mike Judge, R. Crumb, and Leonard Maltin, among others. These aren’t just celebrity cameos. These are people who genuinely understand what Friedman’s doing and why it matters.

The documentary’s title invokes Vermeer, which might sound pretentious until you think about it for a minute. Both artists worked with obsessive precision. Both found meaning in subjects that others considered mundane. Both had an almost archaeological approach to capturing specific moments in time. Vermeer painted Dutch housewives and pearl earrings; Friedman draws liver-spotted elevator operators and forgotten vaudevillians. The comparison holds.

What’s smart about Dougherty’s approach is that he frames Friedman’s career as an evolution rather than just a timeline. We follow the artist from the underground comics scene—where guys like R. Crumb and Art Spiegelman were reinventing what comics could be—all the way to getting his work on the cover of The New Yorker. That journey from counterculture to cultural establishment could’ve been presented as a typical “artist grows up and sells out” story. But the film recognizes something more interesting: Friedman didn’t really change. The culture just finally figured out what he was up to.

The underground comics movement of the ’70s and ’80s was all about pushing boundaries and mixing high and low culture. Publications like RAW and Weirdo existed specifically to offend mainstream sensibilities. But Friedman, even back then, was operating differently. While his peers were trying to shock people, he was already engaged in his strange preservation project, using his technical chops to document aging performers whose time had passed.

The film’s best moments explore Friedman’s quiet focus on entertainers of yesterday, the subjects that fill many pages of his books. Through interviews and archival footage, we start to understand that this isn’t just nostalgia. The Borscht Belt performers, in particular, represented something specific: a moment when American Jewish identity was caught between the Old World and the New World, when immigrant anxieties got transformed into entertainment. By documenting their lined faces and tired eyes, Friedman does something that academic historians can’t quite pull off. He preserves not just what they looked like, but how they felt.

Maron and Oswalt, both comedians who know how precarious show business careers can be, talk about Friedman’s work with real understanding. There’s an unspoken recognition that Friedman’s subjects could easily have been them, that the line between success and obscurity in comedy remains terrifyingly thin. That awareness gives their praise more weight. They’re not just complimenting a talented artist; they’re acknowledging someone who honors their profession’s forgotten dead.

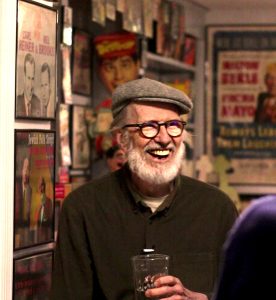

Crumb’s appearance provides crucial context. Crumb basically invented underground comics as we know them, and Friedman clearly learned from his technical skill and willingness to show uncomfortable truths. But as several people point out, Friedman avoided the psychosexual chaos and deliberate provocation that defined so much of Crumb’s work. Friedman’s art works differently—less confessional, more like cultural anthropology. Where Crumb looked inward at his own neuroses, Friedman looked outward and backward at cultural history.

The documentary’s examination of Friedman’s technique is genuinely fascinating, especially if one cares about the technical rigor of the craft. His stipple method—building images through thousands of individual dots—is both old-fashioned and perfectionist in an era when you could just do everything digitally. Watching footage of Friedman hunched over his drawing board, methodically placing dot after dot, you realize the almost religious devotion required. A single portrait might take weeks or months. That time investment mirrors the lifelong careers of his subjects. The technique isn’t separate from the meaning; these forgotten performers deserve exactly this much painstaking attention.

Dougherty shows admirable restraint as a director. He lets Friedman’s work take center stage and doesn’t try to manufacture drama where none exists. Friedman comes across as refreshingly normal—no addiction stories, no romantic disasters, no grand manifestos about the meaning of art. Just a craftsman who figured out what interested him early on and has pursued it with remarkable consistency across four decades and sixteen books.

The film’s later section, covering Friedman’s rise to mainstream recognition including multiple New Yorker covers, raises interesting questions. Did Friedman’s work change to fit these prestigious platforms, or did the platforms evolve to recognize what he was doing? The documentary suggests the latter. Friedman never compromised; he just kept working until the right audience found him.

Screenwriters Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski—who’ve made careers out of movies about showbiz outsiders like Ed Wood and Larry Flynt—offer particularly sharp insights. They recognize in Friedman’s work the same impulse that drives their films: the need to illuminate the margins, to find meaning in lives that conventional history ignores. Their presence reinforces what the film is quietly arguing: that Friedman’s portraits are a form of biography, each face telling a story about ambition, disappointment, resilience, and the weird bargain that show business demands.

What makes Vermeer of the Borscht Belt work is that it treats Friedman’s project as genuinely important rather than just quirky nostalgia. Friedman has created an archive of American entertainment history that doesn’t exist anywhere else with this level of detail and compassion. In an age when everything’s digital and disposable, his stippled portraits insist on permanence. They demand sustained attention. They argue that we have an ethical obligation to remember the people who entertained us.

The documentary honors that project by creating an equally careful record of the artist himself: making sure the guy who documented all these forgotten faces won’t be forgotten in turn. In doing so, Dougherty has made more than just a film about an artist. He’s made a tender meditation on memory, obsolescence, and what happens when someone decides that attention itself can be redemptive. In Friedman’s universe, populated by has-beens and never-weres, every face matters. Every life contained multitudes. Every forgotten performer deserves to be seen one more time, rendered with obsessive care, dot by meticulous dot.

Drew Friedman: Vermeer of the Borscht Belt is now available to purchase or rent in the U.S. and Canada from digital platforms such Apple, Amazon Prime, and Fandango At Home.