Having worked as a journalist since the late 1990s, I have found that most people have no clue about how news organizations work, which leads to a lot of confusion about how the news gets delivered and why certain news gets delivered while other news does not. There are tons of intricacies we could go into, but the most basic reason that things work like they do is that journalists are, like doctors, cops, soldiers, teachers, and politicians, human beings and subject to the same capacity for bad decisions and lack of vision. Their humanity can elevate their efforts or taint them.

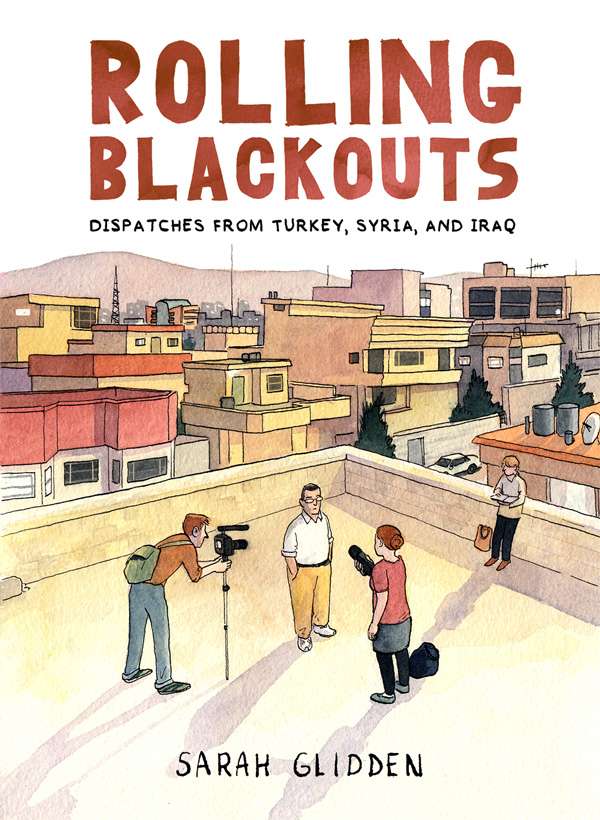

Sarah Glidden’s Rolling Blackouts captures this perfectly. On one hand it’s an account of a two month journey through Turkey, Syria, and Iraq, and a compelling record of the stories and situations that Glidden encountered in these countries, but on the other, and this was certainly Glidden’s intention, it is journalism about journalism, an investigation about how journalism is done.

In many ways, the journalists Glidden accompanies, her friends Sarah and Alex, are not typical. They are independent journalists who have freelance arrangements with a variety of outlets, so they sometimes have a little more lee-way with their approaches and insights than a staff reporter would have. Sometimes, though, their stories get rejected and this advantage doesn’t really matter, but behind the scenes, their independence does give them more opportunity to approach the intent of their work on a philosophical, and therefore more thoughtful, level that a mainstream staff reporter might not be able to afford themselves.

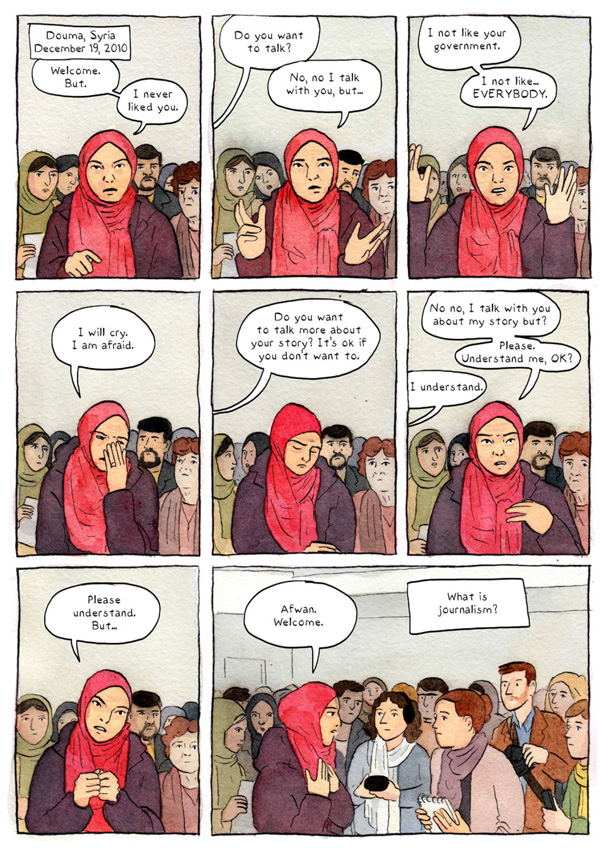

Their goal of this trip is to investigate stories that the mainstream media spend less time on, often human-centered stories with larger political impact, and with Glidden, they are specifically looking at Iraqi refugees with a mission to enlighten and inform Americans about the reality of actions in the Middle East.

To complicate the dynamic on this trip, journalist Sarah’s childhood friend, Dan, who fought in Iraq in the military, also comes along, with the idea that part of their story will be about his return to the region in an attempt to understand better the implications of his own actions there.

To be clear, this is not quite Joe Sacco territory, which tends to be gritty and fraught with the feeling of danger — Glidden’s charming cartooning style, a little bit Herge, a little bit Rutu Modan, is more apt to soothe than to elevate signs of alarm — but that’s not the point either. Glidden’s experience is one that recounts the firsthand tales from the mouths of the people that lived them, which is no less powerful, but is an important distinction, since a lot of the action involves people in rooms and at tables discussing things. And while some of those discussions are about the horror and personal loss faced by the subjects of the reports, many others are about the journalists themselves traversing this hard emotional territory and weighing their obligations to various people in the journalist equation, from their subjects to their potential audience.

As such, Glidden manages to capture a fascinating dynamic and one that is, honestly, far less covered than the tragedies that permeate the lives of the subjects — the process of getting their stories out there by collecting the information that goes into these presentations. This provides Glidden with an opportunity to not just capture the conversations with the subjects and the stories the subjects tell, but also the wider backgrounds of different events, various players, and certain organizations, providing pictures both big and small for a more complete overview in a work that is packed with information.

And while this is technically a work of comic book journalism, at its core it is a drama. Part of that drama involves a young journalist still forging ahead in her chosen profession. Journalist Sarah’s professional outlook is challenged when she begins to mix her personal history with the subject of her coverage by bringing along her childhood friend, Dan.

There are obviously expectations in the interview scenes and part of the tension is that Dan can’t live up to the journalistic expectations in the same way strangers can. It speaks to the idea that maybe the surest way to tell someone’s story is to approach it with a blank slate and allow it to come out in the interviews on its own terms. But it can’t with Dan. There are pre-conceived notions built around personal histories, and these are hard to just push aside when they are ingrained in the interviewer, and at odds with some of the objectives of the reporting.

This dynamic creates the real tension in Glidden’s book, forming the thread that weaves amongst all the locations and passing strangers with heartbreaking stories. It’s the dynamic that personalizes the larger story of covering the Middle East, of Glidden documenting how journalism works. It brings the whole thing right down to earth as it also provides a parallel to the larger, geo-political story that Glidden captures — actions on the world stage affect the small corners of our lives, and the solutions are seldom obvious or easy, and the worst case scenario is that there are no solutions.

If there’s anything frustrating about Glidden’s book, it’s something that isn’t her fault nor the fault of the journalists she travels with. There’s a lot of talk in the book that revolves around the importance of getting the information out there and reveals not only the passion and sense of responsibility that can get wrapped up in journalism, but also the wishful thinking. As our intrepid journalists struggle in Glidden’s story to get real information about the Middle East to the American people, we sit on the other side of a Trump victory and you have to wonder if the American people actually care about any of this information. I applaud and admire people like Sarah and Alex for trying to get it out there, but I’m disappointed that too often their energy and effort only ends up only further informing the ones who already know anyhow, especially in regard to in-depth news about refugees in the Middle East. America isn’t much interested in knowing the other these days, and I don’t know how to turn that around.

That’s the sad state that journalism has found itself in currently. Glidden’s exceptional book, if nothing else, offers some of the tools required to help bring journalism to a better place, and the first of these is thoughtfulness.