Everyone knows about the wider mythologies that creep their way into childhood, everything from Bigfoot to Slender Man that infects young brains in a way that the most fantastic fictions mingle with the drudgery of normal life. But there’s also all the local lore that doesn’t necessarily make it out into the wider world, the strange intimate myths about neighbors and about parts of the neighborhood that resonate with the kids, get passed around, and might even have a direct effect on comings and goings. This is how the fantastic fictions do more than mingle — they meld with normal life so seamlessly that they are just a palpable part of it.

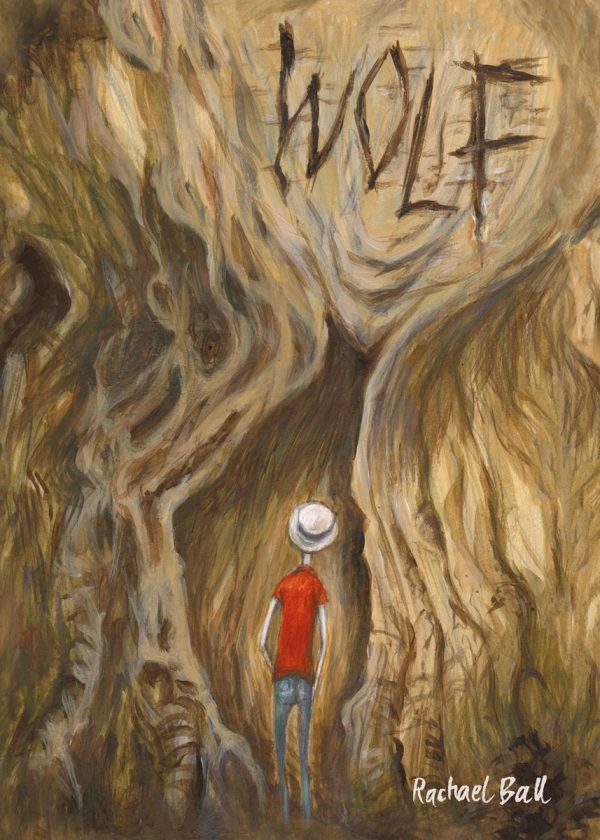

In Rachael Ball’s pencil-rendered Wolf, local lore plays a large part as a British kid attempts to move past the death of his father by letting an opportunity for adventure engulf his being.

It’s the summer of 1976 when Hugo’s dad dies. It’s an accidental death and a kind of madcap one that has Hugo’s dad stumble into his demise after being clumsy with a rooftop camera. But the last day of his life consisted of an outing with Hugo where they find an amazing, huge tree stump. Counting the lines to find out the age, the dad turns them into markers for specific historical events, transforming the stump’s presence into a form of time travel for Hugo.

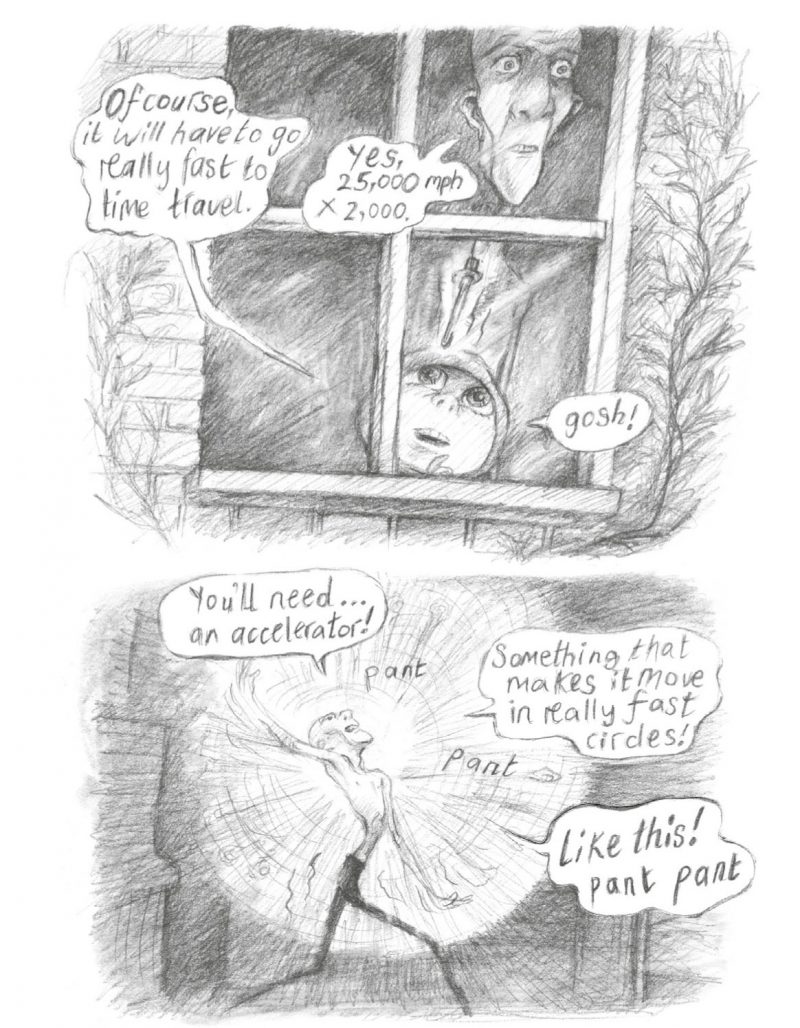

Later, when adjusting to a new house, new neighborhood, and new friends as his mother tries to start over with the family following her husband’s death, Hugo’s siblings and friends begin to collaborate on a contraption inspired by an afternoon’s viewing of the 1960 film The Time Machine. It starts with gathering junk parts and putting them together into what Hugo proclaims will be a time machine, but some genuine engineering begins to turn it into a pedal-powered go-kart, which elevates Hugo’s hope that he will have a time machine to help him reconnect with his father.

There’s one hitch, though — a much-needed part is contained on a disused bicycle in a neighbor’s backyard. That neighbor, known to the local kids as “the Wolfman,” is presented as a clear danger to the kids. That is, he eats them, and one eyewitness is more than eager to attest to the fact.

Whenever a mysterious, cloistered, and possibly dangerous neighbor appears in a story about kids, it is inevitable that a meeting with the mysterious, cloistered, and possibly dangerous neighbor will follow. And it’s also inevitable that they aren’t going to be quite what you expect.

As with the trope, Ball’s depiction of the Wolfman manages to be sympathetic and still disturbing. You find that there are reasons that the kids told stories because that’s how kids qualify what they don’t understand, but you also find that while the stories might have captured the ambiance of what they witness, they don’t quite get to the truth.

It’s in this way that Wolf flirts with the coming-of-age trope, but instead of one where a kid grows up in awareness, it’s more of a first encounter with innocent darkness. It was foisted upon Hugo and through the Wolfman, he finds that he’s not the only one be engulfed by it. It’s a hard lesson for Hugo to learn at first, and he doesn’t want to align himself with the peculiar recluse, but, like so many people, Hugo begins to find a connection through shared darkness.

He also finds closure to his dad’s death, in some ways by being very much his dad’s son. I won’t go into the details for fear of spoiling it, but let’s just say a lack of common sense has moved through the genes.

Wolf finds the people forced into change typically learn to adapt, and people faced with darkness typically learn how to live with it. The pencil artwork makes the story seem urgent, current, very much alive as if sketched hurriedly in order to get the message out there, but also to capture the frenzied quality of childhood summers when dark fictions become the structuring narratives of your everyday existence, and you embrace them.

Comments are closed.