There have been several good works over the past few years – Here, A Castle In England, and 750 Years In Paris come to mind – that examine the idea of place, and each of them does so in the context of human presence and place as something that transcends that. Chris Ware’s Building Stories create even more expansive, fussier, thematic complexities out of this idea.

I suppose it’s fair, since place in these terms require human construction, and in context of works that examine buildings, perhaps the most significant aspect of such structures is that though we create them, they exist beyond us. Their evolution is so vast that the human eye cannot perceive it in real time. These structures outlast us; they are like gods that we create and then take on an existence of their own.

But if there are major gods, then there are probably minor ones too. Definitely there. They exist in the form of abandoned bikes, fences, roads, sewers, and park benches.

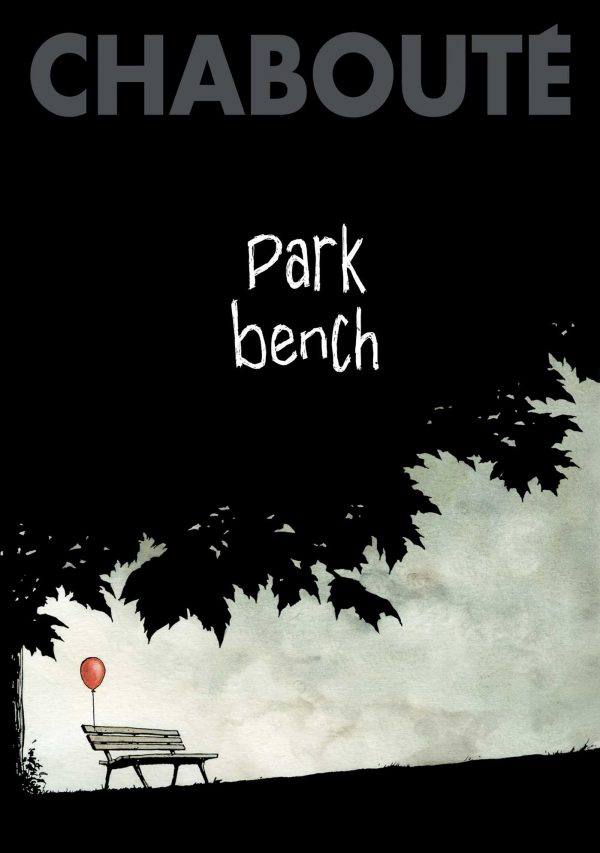

It’s this latter one to which Chaboute has devoted over 300 pantomimed pages in the straightforwardly titled Park Bench. What the title promises is exactly what you get, a narrative about a park bench that sits in the same place day after day, and the slices of people’s lives that intersect with it when they take a moment to sit on it or just pass it by altogether.

Maybe the bench’s function is to be a more mundane version of the monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey — less omnipresent, less powerful in general, but still a watcher in time and touchpoint for certain human revelations.

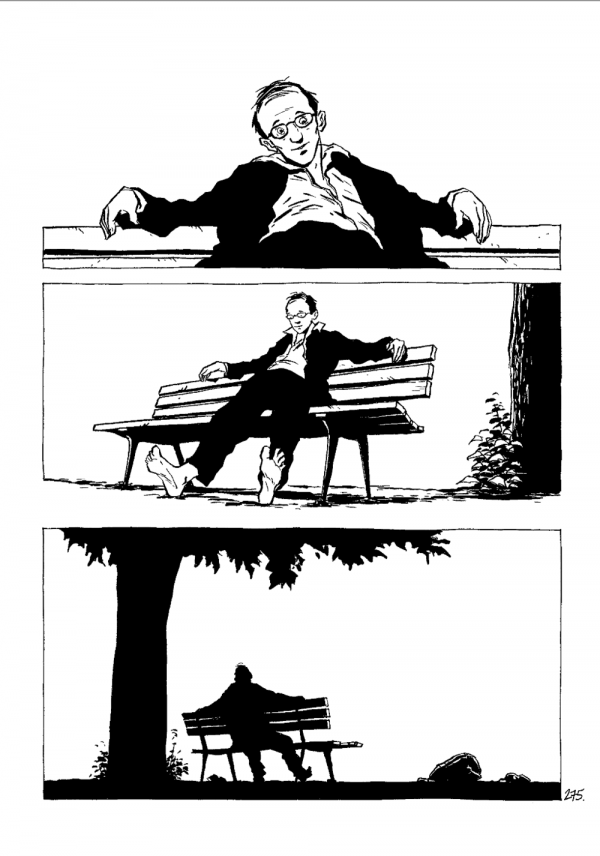

Or maybe it’s more passive than that. It’s a point in space where people routinely go to rest their feet, to spend some time reading, to sleep, or to wait for the next thing to happen in life. Some who access it for that latter reason are often tethered to tragedy and sadness — men being stood up on a blind date, men being forced into retirement, lonely women reading romance novels, the homeless looking for some safe haven.

Sometimes these moments of usage set up strange bedfellows, as when a street musician sets up — rather rudely I thought — to busk regardless of who else is setting there, or when the retiree bonds with the homeless man. Sometimes it’s between objects and humans, as when the young skateboard dude becomes fascinated with a discarded book, even as his friends heap ridicule on him.

As a public social space, the park bench is fixed point where anything can happen, particularly change. It is the opposite of a safe space. It is an outpost where people intersect with each other, often uncomfortably. But if you accept it as a microcosm, it seems that Chaboute is saying it’s only by working through the discomfort that anything eventually happens. Discomfort is a universal constant and a human requirement for change, and it’s contained in deceivingly static spaces like park benches. Not static emotionally, though.

Of course in Chaboute’s final summation, we don’t acknowledge the importance of such spaces — or more to the point, we don’t recognize that the fussier you become about them, the less pure the experience becomes. That too is part of the microcosm, a regular plot point in the sweeping human fable, and this simple graphic novel is probably victim of the same dynamic. Simplicity goes about its work quietly, its effectiveness never celebrated, because that would destroy its power.