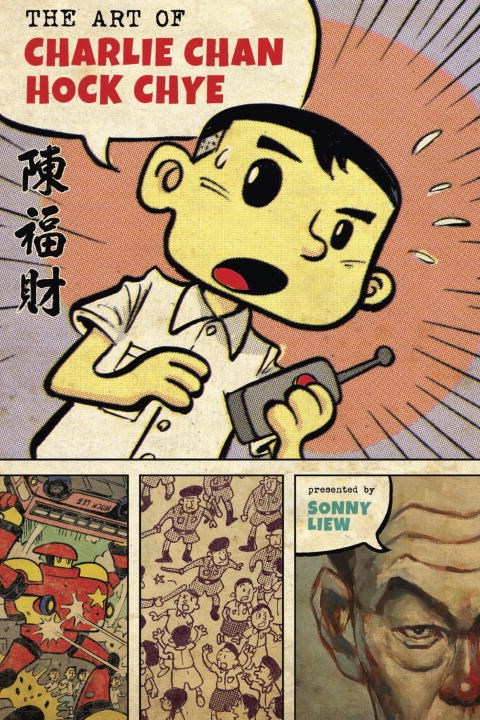

The Pantheon library of graphic novels is indeed a fairly hallowed one, publishing works such as Black Hole, Persepolis, David Boring, Here, Asterios Polyp, and of course, Maus. Sonny Liew, known by the weekly comic readership as the artist of the severely under-read Doctor Fate, and half of the team of 2014’s excellent The Shadow Hero, makes his Pantheon debut with The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye.

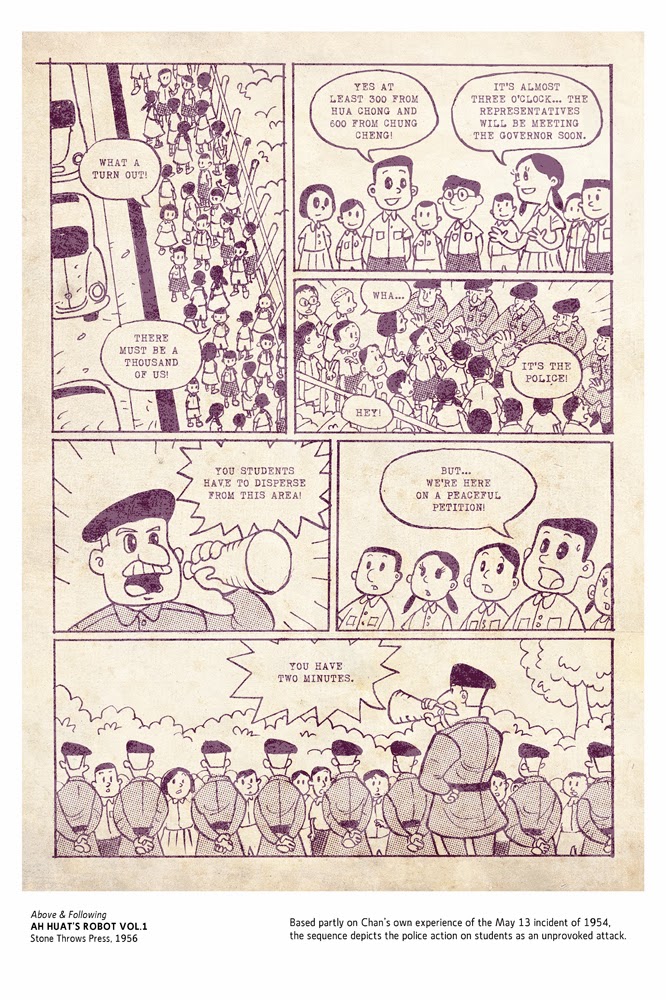

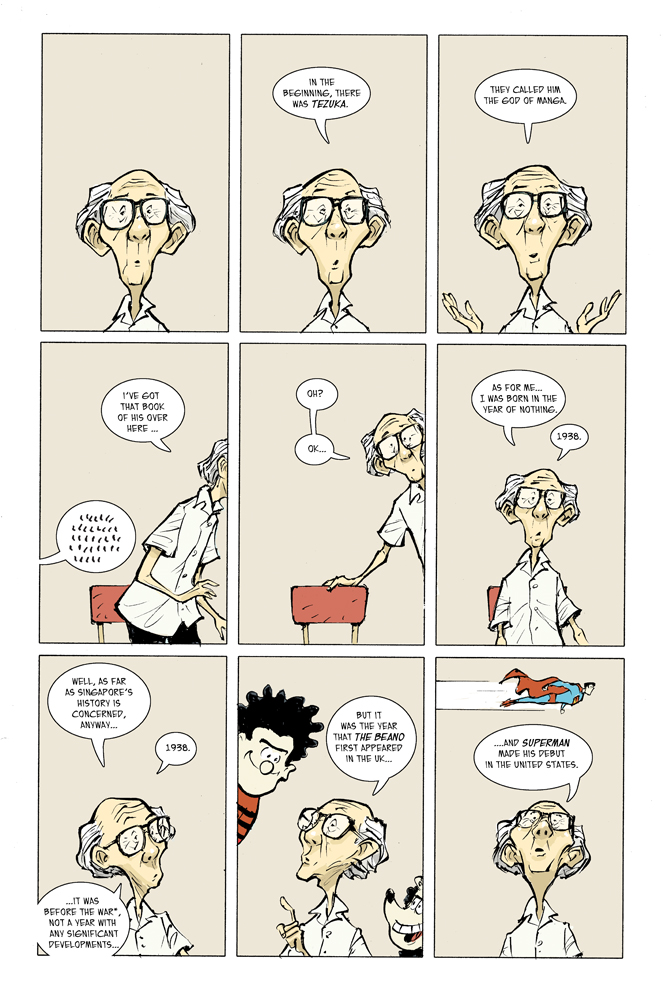

The book in question delves into the life, work and political leanings of “Singapore’s most famous comics artist”, the ubiquitous Chan Hock Chye. Born in 1938, Chan’s only passion in life is to draw comic books. Inspired by the work of legends like Osamu Tezuka and Carl Banks (whom he’d read at the local “pavement libraries” in the city-state), he sets off to create his first character: the Astro Boy inspired “Au Huat’s Giant Robot”, a giant robot that only responds to commands in Chinese. That latter detail is particularly important as it sets into motion the kind of cartoonist that Chan will grow into, one that is particularly moved by the cultural and political moors of his home.

This is an awfully impressive achievement given that Chan is a fictional character.

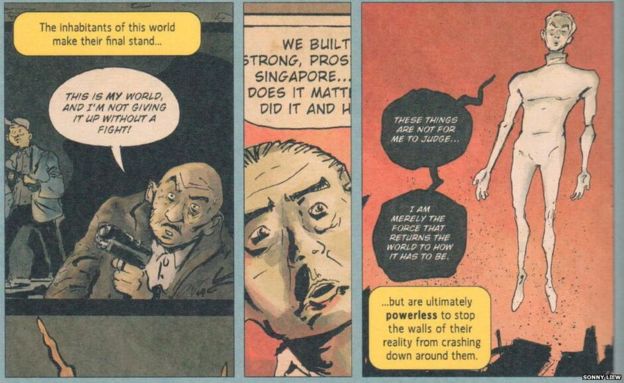

While the subject matter of The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye centers on the life and times of the creator it’s titled after, the potentially richer portion of the text is focused more on Singapore’s history and how Chan views it through the lens of the artist. Chan himself is a fiction utilized to convey the ever shifting political landscape of Singapore, from British colony to Japanese occupation to the rise of its own self-governance, with a failed merger with Malaysia in between. This theme is nailed with a hammer from the proverb that sits inside the cover: “One Mountain Cannot Abide Two Tigers”. Those two tigers that Liew references are the recently passed long-time political leader Lee Kuan Yew and the slandered and wrongly imprisoned Lim Chin Siong, two men that once worked together for Singapore’s future but found that political power could only be centered in one individual.

Chan’s work is highly indebted to the impact that both of these players had on his native land, and they make appearances throughout all of his comics in some form or fashion (as tag-teaming science fiction heroes against an alien stand-in for their British authoritarians, as Pogo-like funny animal characters, and revolutionary figures that are none too dissimilar from what might appear in work inspired by Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns). While Liew also has Chan set his sights on Singapore’s economic and socio-political troubles in a broader sense, it’s his even-handed focus on these two towering figures and the inherent tragedy of their one-time partnership gone sour that makes the book work best.

Liew swings a particularly tough dramatic punch by the story’s back-half, at the moment when Chan’s partnership with writer Bertrand Wong comes to an end due to the need to find a “practical vocation”. This dovetails with Lim and Lee’s partnership dissolving and the mindset that Singapore found itself in during its post-failed Malaysian merger. At this point in time, the Lee Kuan Yew led government began to guide the newly independent nation with a strong hand, leading to economic growth but also crushing needed freedoms, such as Lee’s need to overtake the press in an attempt to quell any personal or political causes that may speak out against the ruling regime. The question posed by Liew (vis a vis Chan) is one of “what do we leave behind in order to gain material prosperity?”. Chan’s spirited approach to his own comic output stands in firm opposition to the idea that giving up those types freedoms would stifle his artistic expression.

The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye arrives in stores today via Pantheon.

Comments are closed.