by Carol Tilley

The business of early comic book publishing in the US is something of a black box: too little data about actual practices, too many secrets in the name of competition, and too much self-aggrandizement in lieu of actual information. What we do know is kludged together lovingly by a small army of devoted comics historians from oral histories of aging comics pros, scant extant company records, occasional legal proceedings, notices in trade publications, and similar bits.[1] It’s a documentary amuse-bouche, but one seemingly without the promise of a main course. Last year in the course of doing some research on comics readership, I stumbled across an interesting work that, while not providing a main course, perhaps at least gets us closer to an entrée.

David McKay Company was a Philadelphia-based publisher, founded in the 1880s. McKay published eclectic materials from the complete works of Shakespeare, detective fiction, and children’s books alongside titles on home economics, animal care and parlor games. In the early 1930s, McKay issued a handful of hardcover comics reprints including Mickey Mouse and Popeye. By the mid-1930s, McKay had brokered a deal with King Features Syndicate to repackage their newspaper comics—Katzenjammer Kids, Blondie, The Phantom, and other titles—as floppies. These reprints were published under three titles, Ace Comics, King Comics, and Magic Comics. The first two ran for more than 150 issues each with Magic making it for more than 120 issues. Feature Book, another McKay comics title, accumulated more than 50 issues; unlike its siblings, each issue of Feature included stories from a single property.

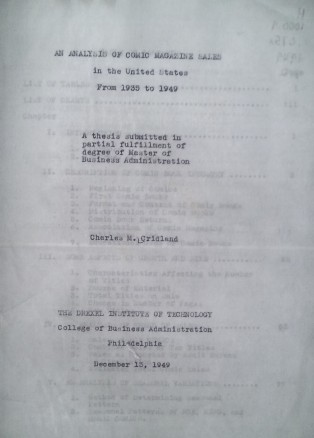

In the 1940s, a young accountant named Charles Cridland took over as treasurer for McKay. Cridland, who grew up in the Philadelphia area and was himself the son of an accountant, was married to Margery McKay, the granddaughter of David McKay and the daughter of Alexander McKay, who was then the company’s president. He and Margery may have been high school sweethearts, as they were both members of the Class of 1932 at Upper Darby High School. “Charlie,” pictured here in his senior class photo, was ribbed in the yearbook about being “quite a naturalist,” who was especially interested in “Boyds.”

Cridland’s motivation for choosing this particular topic for his thesis was practical. He wrote that when he took over the comics division for McKay, it “was then publishing five or six titles with an annual sale in excess of twenty-five million copies. I soon found that there was little available in the way of management tools to effect any informed decisions.” He goes on,

The main problems facing each publisher are first, to set print orders for each issue so that there are sufficient copies for adequate distribution and at the same time to keep returns of unsold copies to a minimum. Second, each publisher must decide on the advisability of of adding new titles and of discontinuing old ones. For the industry these two problems have existed since the end of the war and have become increasingly pressing. Excessive returns due to unbalanced production have been increasing. In turn there appear to be too many different titles (pp. 1-2).

Cridland was both a rationalist and an optimist: if he could document and analyze comics sales over time, looking for patterns with regard to seasons, pagination, and frequency, perhaps he could improve the industry’s bottom line. A handful of folks including some of the officers of the recently formed Association of Comics Magazines Publishers (ACMP) were excited about the possibility of wide-scale cooperation. But, as you might suspect, the industry as a whole wasn’t ready for management efficiency. Cridland writes,

Unfortunately, the comic magazine industry by its very nature has not been conducive to cooperation. Specific sales information concerning particular titles gives competitors results of perhaps expensive testing. It also invites immediate competition in the form of similar magazines…Very little information regarding sales is available. Estimates have been largely guesswork and most decisions have probably been of a similar nature (p. 2)

An even more sobering paragraph follows.

Before attempting to gather data, I spoke with many people in the industry. All of them thought that such a study would be extremely useful but most stated that I probably would not be able to obtain material. While I was able to gather material, it was extremely difficult and my being known in the industry probably accounts for this limited success (p. 3, emphasis mine).

After laying out his rationale and method in the opening chapter, Cridland uses the second chapter to provide an overview of the comics industry. Some of the history and explication in this overview is familiar even to the casual student of comics history, but there are some less common insights. For instance, it may seem counterintuitive, but repackaging newspaper strips in comic book form is viewed here as a more costly endeavor than creating wholly original material.

However, to adapt it to comic book form it was necessary to rescale and reballoon it to comic book size. And, since the newspaper strips were often produced for black-and-white daily papers, it was necessary to make color schemes (p. 8).

Likewise there are some useful insights into accounting practices related to distribution and sales.

Some distributors make a first payment of twenty-five percent as soon as distribution is completed…the final payment for an issue of King Comics is made at least sixty days after the off sale date, and then some adjustments will continue for another two or three months until the exact final net sale can be determined (p. 12).

Cridland also outlines the pricing structure. For a 10-cent comic, wholesalers paid 6-cents, which he says had just been negotiated to 5 ¾-cents for the majority of them, which some urban wholesalers were already paying. Wholesalers charged retailers 7 ½-cents per issue. For each issue sold, wholesalers kept a brokerage fee of ½-cent. Thus publishers grossed 5 ¼-cents for each sale, retailers 2 ½-cents, and wholesalers 2 ¼-cents. Unsold issues might be resold as premiums (e.g. 25 for $1) for use at movie theaters and similar businesses. They might also be sold overseas—although Cridland notes this practice had been largely curtailed because of currency devaluation—or donated to veterans hospitals, prisons, or other institutions.

In the third chapter, Cridland begins to provide some specific information about manufacturing and sales. With regard to manufacturing cost, Cridland cautions that his information should be viewed as an approximation.

Including all costs assignable to printing an issue and before considering overhead, the publisher of a magazine must sell from fifty to sixty percent of print order to break even. These break even points are applicable on a printing of from three hundred and fifty thousand to five hundred thousand copies [Earlier he states that a 500,000 printing would be high, and that an 80% sales rate would be viewed as strong, although he also notes later that during the war-era paper restrictions, printing runs sold at nearly 100%] (p. 24).

Using data gathered by Edward and George Dougherty in their Comic Magazine Publishing Report, a monthly bulletin of on-sale dates for comics, Cridland compiles a comprehensive tabulation of the numbers of comics titles on sale each month between January 1942 and October 1949, both as aggregates and by periodicity (or frequency). The low point in the range is 99 titles in June 1942, and the high end is October 1949 with 326 titles. With a few exceptions, the number of titles between 1942 and 1945 stays between 120 and 150, but in 1946, the number of titles begins to balloon. Here the range is 175 to 222. In 1947, it moves up: 198 to 226; 1948 sees it tick higher, 237 to 299. The ten-months reported for 1949 gives a range of 292 to 326. Bi-monthly and quarterly titles accounted for most of the growth during the decade.

The fourth chapter rewards the reader with some specific sales figures. Cridland uses Ace Comics as a single case. Full-year sales fluctuated for this title from a low of 2,004,000 (223,000 average per issue) in 1937 to a high of 5,761,000 (476,000 per issue) in 1945. Between 1947 and 1948, sales dropped by nearly 50%, a drop made more vivid by an accompanying chart that depicts an almost cliff-like edge. Cridland writes,

Sales during 1947 and 1948 show a very rapid decline from this unusual and highly satisfactory condition. Generally, when a title is made into a bimonthly from a monthly some increase in issue sales can be expected. In the case of Ace Comics, this was barely discernible. Actually then, Chart X represents the life cycle of this magazine; and, while the growth from 1941 through 1946 may indicate the situation for many other comic magazines, the subsequent period does not (p. 67, emphasis mine).

The final issue of Ace bore the October-November 1949 date on its cover. In fact, all of McKay’s comics ended their runs that fall. More phenomenal sales growth awaited publishers that could or chose to hang out, but McKay was finished with its comics gambit.

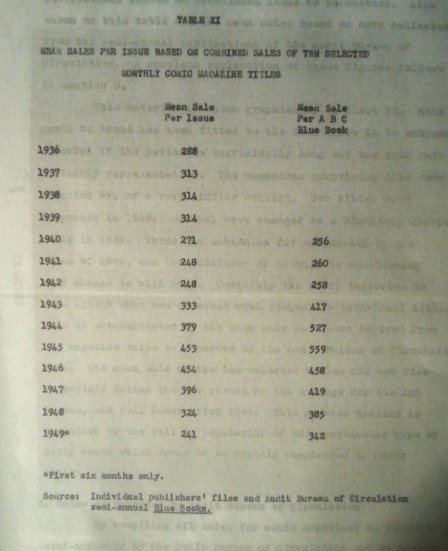

Cridland offers more sales data, though, in this chapter. Here I include a photograph of the table, Table XI, in which the sales of ten titles are compared against sales Cridland calculated for all titles reported by the Audit Bureau of Circulation (ABC). He does not name the ten titles, but three of them are likely Ace, King, and Magic, as he notes that three were being suspended at the end of the calendar year. Few of the ten were viable:

The magazines comprising this combination are of a very similar content. Two titles were suspended in 1948. Several were changed to a bimonthly status early in 1949. Three are scheduled for suspension by the close of 1949, and the publisher of another is considering what change he will make (p. 69).

Cridland delves deeper into the data available in the ABC reports. The ABC (which is now the Alliance for Audited Media) compiles figures from periodicals publishers to help establish reasonable advertising charges. Comics publishers typically reported their sales to ABC not by title, but by group, making it difficult to determine how well particular comics sold. Cridland, though, laboriously figured the numbers of titles represented in the ABC data, weighted them by frequency, and calculated means. Plus, he compared the total number of issues as represented in the ABC data to the number of issues that the Doughertys tallied each month.

The key takeaways are that the mean sales per issue – as calculated from the ABC data – ranged from a low of 256,000 in 1940 to a peak of 559,000 in 1945. For the first half of 1949, the mean sales were 342,000 per issue.[2] While there was a decline in sales per issue after the end of the war, the number of comics on sale increased significantly, driving total sales per year higher. Cridland reports what the total sales are according to the ABC data, but I’m skipping that part. Why? Because he also found that the ABC data accounted for only about half of all of the titles that were actually on sale.

To account for this disparity, Cridland works out estimated total comics sales for the years 1942 to 1949. Here are his figures:

1942 231,000,000 issues sold

1943 407,000,000

1944 518,000,000

1945 532,000,000

1946 644,000,000

1947 641,000,000

1948 728,000,000

1949 750,000,000 (extrapolated from the first 6 months)

These numbers are a little more robust than, but largely consistent with, figures I’ve encountered elsewhere. Certainly they help make sense of the trajectory that led Publishers Weekly in a 1954 article to place annual comics sales above 1 billion.[3]

Except to note that Cridland found peak sales for McKay titles in January and August with a dip in the summer months, I’ll omit his discussion of seasonal trends. Instead, let me leave you with one of his concluding observations.

[I]t should be pointed out that, although the industry is enjoying the highest level of sales since it began, it is highly probable that present operations have resulted in the lowest financial return. Probably more comic magazines are returned unsold today [1949] than were produced in 1946. Because of the lack of mutual trust among publishers, little is known of actual results. During those months of the year when sales can reasonably be expected to be lower due to seasonal slack in demand many print orders are not regulated accordingly.

Conditions in the field of distribution are not satisfactory…Many times large bundles of magazines never leave the wholesaler’s warehouse but are moved from the receiving platform to the return room…

[T]here appears to be a pressing need for complete information. Such factual data could then be combined to furnish industry-wide data so essential to management control. In addition, the continued development and improvement of such management tools would undoubtedly be accompanied by more experienced and competent management throughout the industry (pp. 106-107).

About a year and a half ago here on the Beat, Brad Ricca and Sean Howe shared their discovery of a 1942 graduate thesis by cartoonist Paul Cassidy. Although, as I’ll share in the near future, it wasn’t the first graduate level work on comics in the US, it is unique because of its author: someone in the industry studying industry practices. Cridland’s thesis is intriguing for the same reason, and it offers a useful parallel to Cassidy’s work. In Cassidy’s paper we learn about cartooning practices via a survey; in Cridland’s we gain insights into management and sales via a detailed analysis. Are there other insider gems awaiting us in a library’s stacks? Possibly, but I don’t think so.

Cridland left McKay, although I’m not certain when, and took a similar job with the publisher Thomas Nelson & Sons. He died in 1972. I wonder what he would think of the comics industry today?

About the Author

[1] These historians include Brad Ricca, Sean Howe, Gerard Jones, and Michael Barrier. I have great respect for the work they’ve done and continue to do to tell the story of comics.

[2] By way of comparison, the top selling comic in January 2016 was Walking Dead #150, which sold about 156,000 copies. John Jackson Miller’s Comichron site contains extraordinary information about comics sales during the past half-century.

Fascinating stuff, Carol. And not surprising that Cridland kept running into roadblocks — he found then a lot of the same ones we’re finding today.

I continue to find fascinating that if the 1 billion-copy figure for 1954 holds, that translates to $100 million retail then and $880 million in adjusted 2014 dollars. The value of the total print comics market in 2014 (including comics and graphic novels, in both comics shops and the book channel) was likely $835 million, with digital adding another $100 million. (It’s looking like 2015’s print market alone will wind up higher than that $880 million, once the numbers are all in.)

By no means are there remotely the same number of readers — but it is an interesting comparison, if we’re contrasting how many people the business is providing a living wage for. It’s just that instead of just sending one format to newsstands, we get to that total in ways never imagined back then.

Maybe I’m supposing too much, but if Cridland got his data from ABC, wouldn’t the very same data be available nowadays at Alliance for Audited Media? Those auditing companies rarely, if ever, throw anything out…

Pedro – The ABC data still exists, but the problems with it are a) it’s represents only about half of the titles that were available for sale, and b) it’s largely aggregated by publisher (e.g. Fawcett’s titles were grouped into two categories and the sales were only reported by category).

Thanks for the explanation! Well, it’s SOME information, at least.

Excellent, fascinating historical work! Kudos to Carol!

Great article and what a find! Just a minor quibble — you should block-indent those paragraphs that come from Cridland’s paper to make clear they’re quotes from his paper!

Hi Randy – The quotes were block-indented in my original draft, but they didn’t get transferred over to the blog post. Thanks!

Comments are closed.