Cartoonist: J Marshall Smith

Publisher: Bulgilhan Press / $21

December 2025

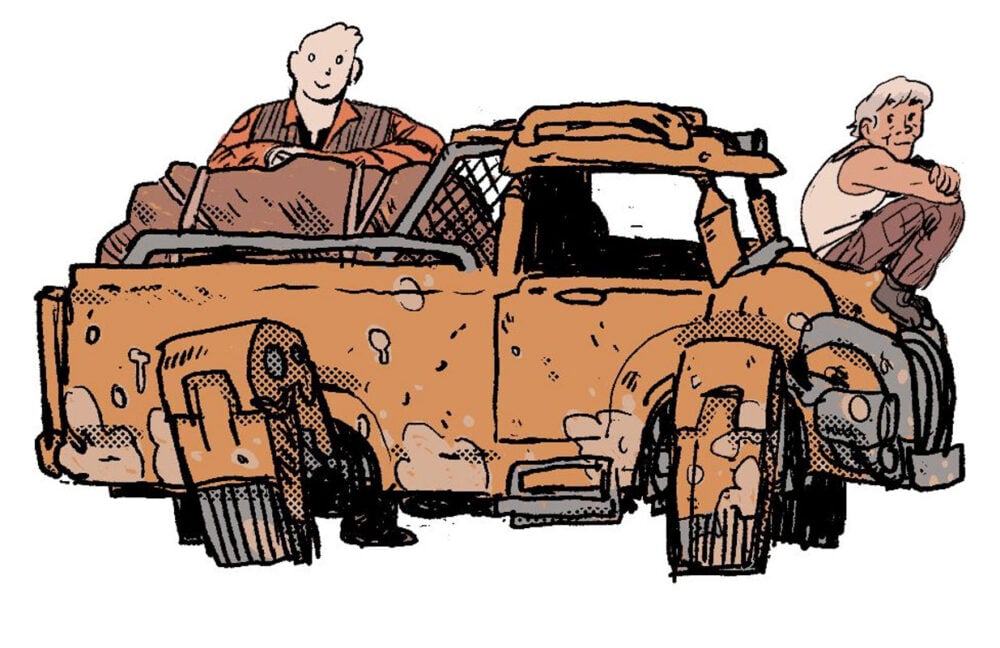

Judith came to this planet in a jar: one of hundreds of scientists, explorers, artists, philosophers, adventurers. It’s a planet too far out for corporate interests to invest in populating, too far away for anyone who goes there to come back. Theirs was a life dedicated to the acquisition and dissemination of unique experiences. And then there’s the mechanical shepherd sent along to watch over them, designation Testament. J Marshall Smith’s Testament might be named for a robot, set in space an epoch away from today and an impossible distance from here, but its concern isn’t science fiction.

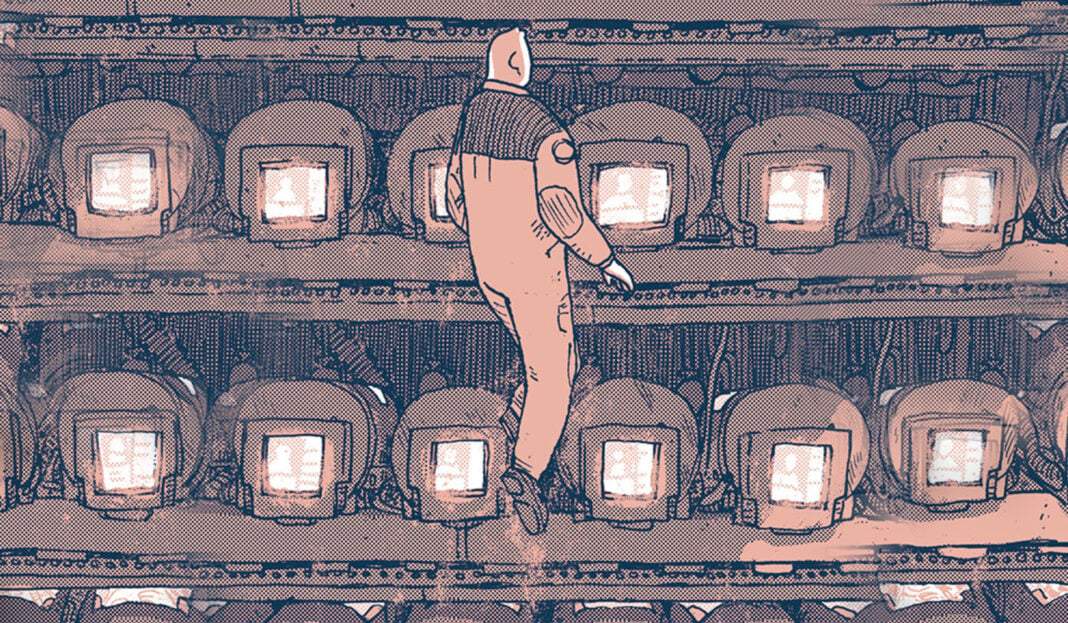

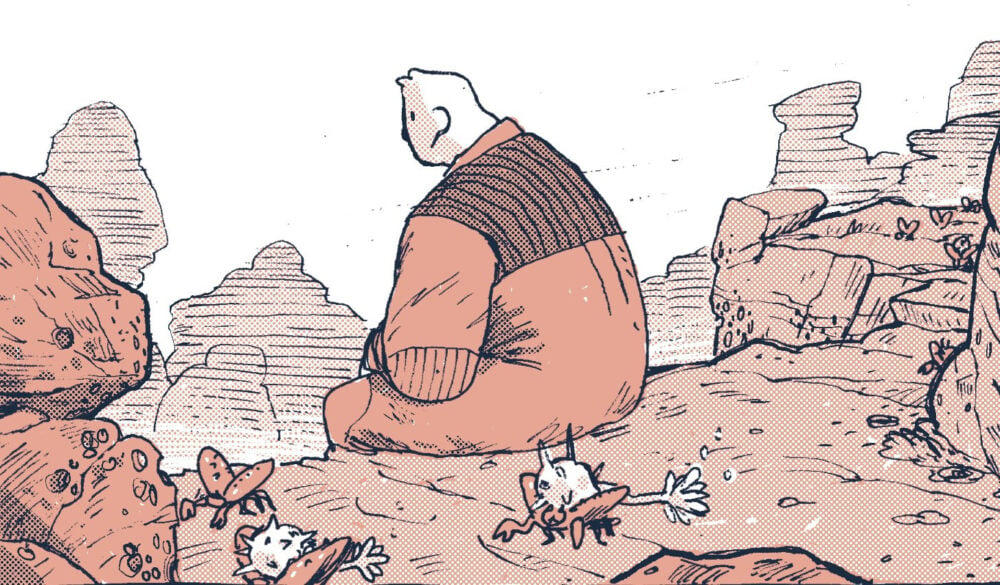

We’re given glimpses of the journey, years of Testament wandering starship hallways while the travelers sleep. Told of the society that was created with ambition, technology, and no small amount of faith upon their waking. Judith gave her life for art and science, so that a legacy of knowledge could be shared by all. And here we are, in the twilight days. Testament is the book closing, as it must for everyone, on every planet. Except Testament, of course. The perpetual energy core that stands in for an android’s heart has a battery life that can last forever.

How do you live on the precipice of an end you know is coming? A kitchen pantry stacked with empty bowls, a cabinet full of cups that will never be used. I found myself looking to Judith for answers rather than Testament. Trying to adequately articulate how I saw the way she has accepted her own mortality without compromising her pursuit of life. Purpose doesn’t require closure to validate it, it needs faith while being pursued. Does that mean that whether or not a thing is left unfinished is arbitrary? Testament, who will go on to live even after the end comes, will have more time to pit these questions against each other than you or I ever will.

But in a total Twilight Zone fashion, we blow past the science fiction premise and get straight to exploring what the human condition reveals about itself when placed in an impossible situation. What persists, what fades. For me, what Testament is going to do with himself for an eternity in isolation after his last friend dies, that’s a haunting question. I love good world building, and Smith does it. But soul searching, that’s harder to come by. So when I say character forward, I mean the book is full of Testament and Judith having fireside conversations about the essence of being, not demonstrating the mechanics of terraforming.

The android heart, a question of emotion’s validity. If you’re programmed to like helping, does that make your pleasure insincere? A character flaw in Judith is her repeated dismissal of Testament’s presence, often to his face, as if she’s the only one whose feelings are genuine. There’s an anxiety in acknowledging you share the same feelings as someone from a group you’ve culturally dehumanized. Judith might be stuck, but Testament bypasses the BS. Regardless of the why, this is how Testament feels. The mystery is what the distinction is between someone’s feelings being real or fake. It seems like we decide based on the identity of the feeler rather than the things they’re feeling.

Testament, listen. To live is to change. The old self dies a thousand times, if you’re doing things right. The fear of losing your humanity to technology, the pieces of yourself being taken away and replaced with so much automata you cease to exist, fails to acknowledge that the original form holds no static state. The Rachel Pollack science fiction prose I’ve read is all about this, too (and how it relates to her experience as a trans woman). While some robot ennui classics invite you to consider this as a “what if” kind of stinger at the end of the story, Smith puts it to work while Testament’s still going.

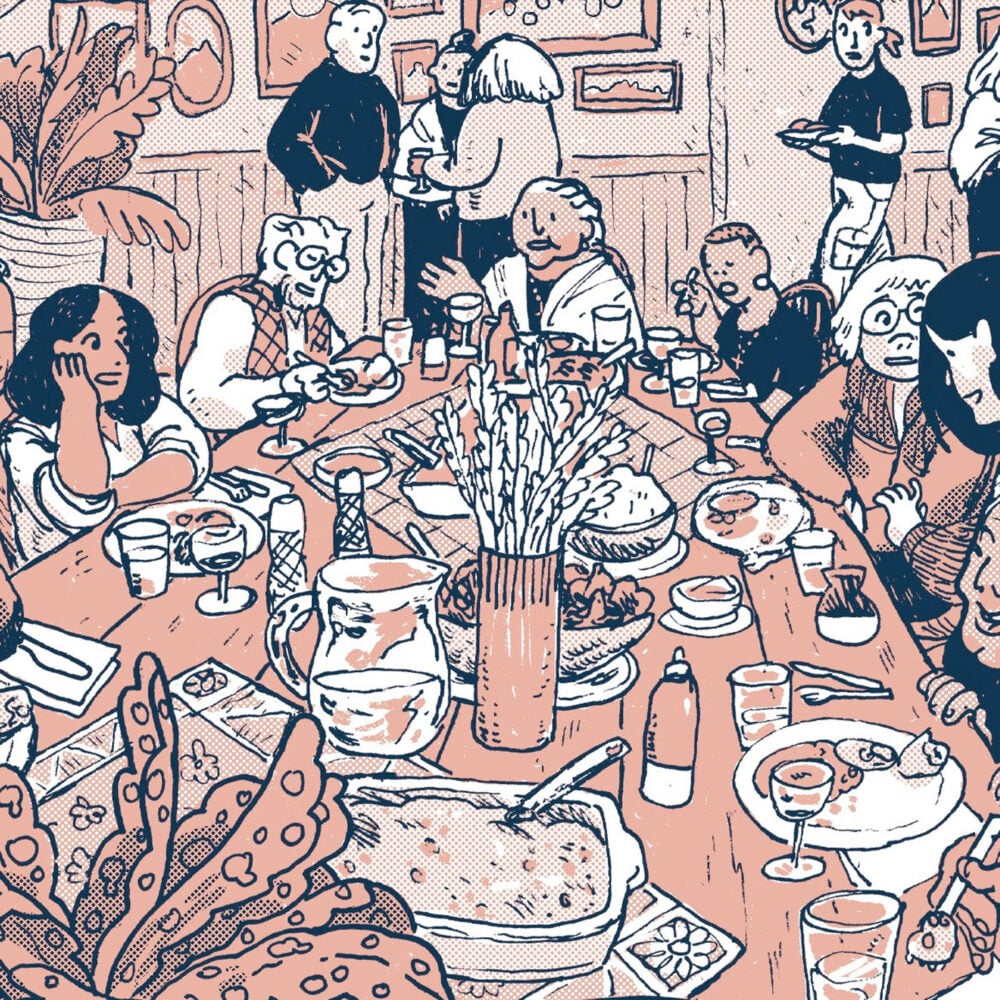

As sad as where it inevitably leads, I gotta say it’s refreshing to read a book with an older woman as the protagonist, more so when she’s both depicted realistically and free from a heavy-handed design that emphasizes her age. Testament is a caretaker, and we see that in the book’s frank depictions of the physical frailty that comes with age. Smith draws with that same compassion, recognizing beauty. Hayao Miyazaki is a king in the feisty old lady game, but all his movies cartoonishly gonk them out, overemphasizing their age in comparison to his beautiful, bishi leads. Judith isn’t Dola, and she isn’t Dandadan Seiko either. She’s just old. It’s nice.

This is not to imply that the artwork in Testament, though it typically favors domestic over fantastic and subtle over theatrical, is in any way lacking worked-in detail. Smith is an artist who is clearly constantly drawing. His linework is full of scribbled in detail, hash marks here and there, giving the drawings a slight texture and depth that sings with confidence. A dance of freedom and control. Even the objects, like the squares of a quilt tucked into a wheelchair, are full of details that speak to the history of the world.

The coloring is just as cerebral, half solid colors to add depth- an offset printing effect that doesn’t clash with the rawness of the illustration, a complimentary flatness. There’s also colors done as Ben Day dots, giving the negative space texture without shaping it the way the solid coloring does. Some panels layer dots on dots on solids so that the shadow on a cheek, the pallor of a face, and the impression made in a pillowcase are all discernibly different. This whole book is layers and layers of Smith’s total devotion.

Out of curiosity, I looked up who Judith was in the Bible; turns out I was familiar with her beheading of Holofernes. Which is definitely not an image I associate with her relationship to Testament. She’s actually an apocryphal reboot. An allegory who gives permission to the pacifist to defend themself. Judith is a lesson. We have the strength within us to stop what matters from being destroyed.

Testament liked tending to his sleeping flock, a gardener in their silent greenhouse, making sure everything is growing and healthy. I think the fear Ridley Scott and Cordwainer Smith choose to negatively cultivate is still there, but (J Marshall) Smith keeps it trapped inside the reader. This comic isn’t about technology without morals compromising humanity. It’s contemplating why people do what people do.

What makes it last is it gives you absolutely no answers. I was left feeling more devastated than hopeful, telling myself stories about what could be happening beneath the planet’s distant, rolling clouds.

Testament is available from Bulgilhan Press, or wherever finer books and comics are sold.