Story & Art: Yupechika

Script Advisor: Marie Nishimori

Translation: Jenny McKeon

Adaptation: Lianne Sentar

Lettering & Retouch: Karis Page

Publisher: Seven Seas Entertainment

In the wide world of comics, there is a general lack of what one might consider truly wholesome content outside of works directed toward a very young audience. But in our turbulent political and environmental times, it is refreshing to have a refuge inside works that promote pure ideals of friendship and embracing differences. Satoko and Nada scratches that itch very nicely.

Satoko is a Japanese student attending a university in the United States. Needing a place to stay for the duration of her education, she applies to be Nada’s roommate. Nada is likewise an exchange student, albeit one from Saudi Arabia. She has had a hard time finding a roommate because many young Americans are wary of Muslims. Satoko, however, does not have the baggage of Middle Eastern conflict in her past, and she gratefully takes the second bedroom in Nada’s apartment.

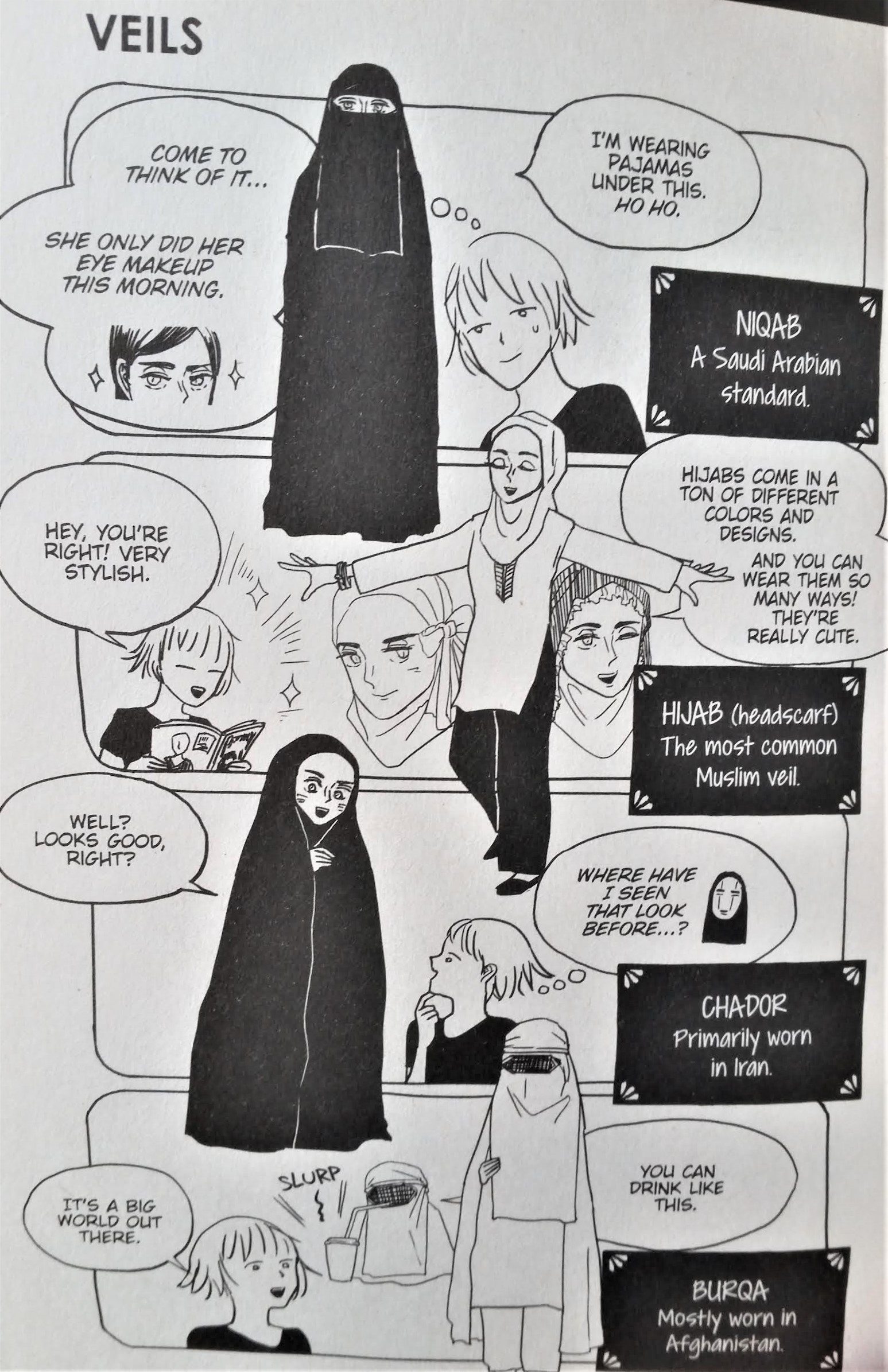

In pages separated into four-panel columns, readers are invited to peer into the blossoming friendship between these two young women. Since Yupechika is writing from a Japanese perspective, a great deal of time is spent learning about Nada’s various cultural and religious customs. This is of great benefit to the American reader, as well, who may have erroneous ideas about Islam and the Middle East. Satoko meets Nada’s other female friends from Saudi Arabia who all choose to dress differently; readers learn the differences between hijab, niqab, chador, and burqa early on in the series, dispelling myths about forced participation in modesty amoung Muslim women.

Turning expectations on their head, Nada is actually far more worldly than Satoko. Nada has to rescue Satoko from a potential abduction at one point because Satoko is too trusting, having grown up in a community where violent crimes are very low. Satoko is also less experienced with makeup or clothing, two things which Nada loves despite (or perhaps because of) her dedication to dressing modestly outside her home. Nada is very dedicated to politics and her hard-won right to vote, while Satoko realizes that she has always taken this particular liberty for granted. And though these two unlikely friends have their differences, both cultural and personal, they also find plenty of ways to connect their seemingly disparate worlds, often through that great unifier — food.

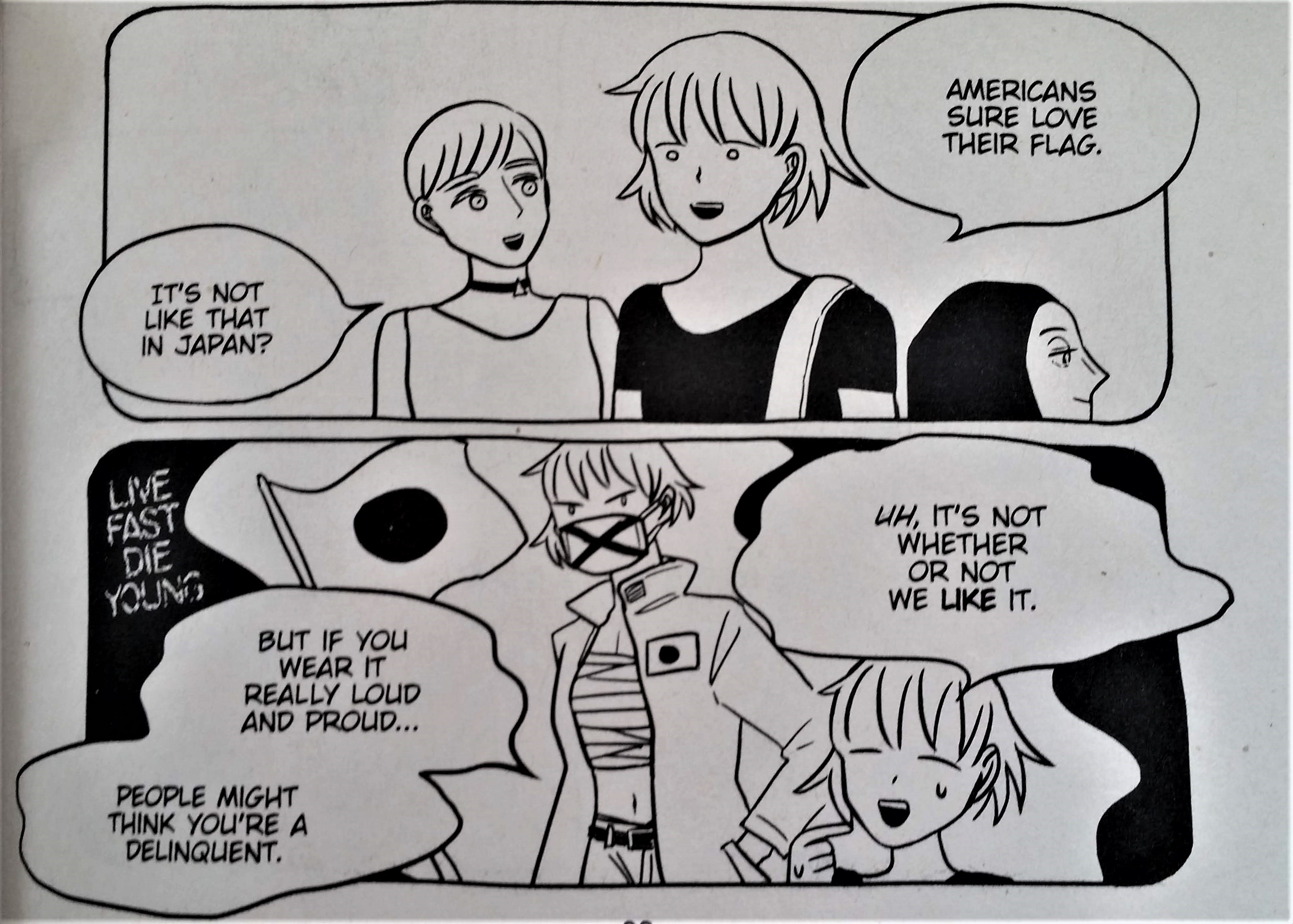

The young women become friends with Miracle, a white Christian American student, and Kevin, a third generation Japanese-American student who is learning the Japanese language with Satoko’s help. So even though the focus of the story is mainly on learning about Saudi Arabian culture and Muslim religious practices, the differing perspectives of multiple students help to round out Satoko and Nada’s experiences in their new, temporary home and allow them to learn about American culture while learning about each other.

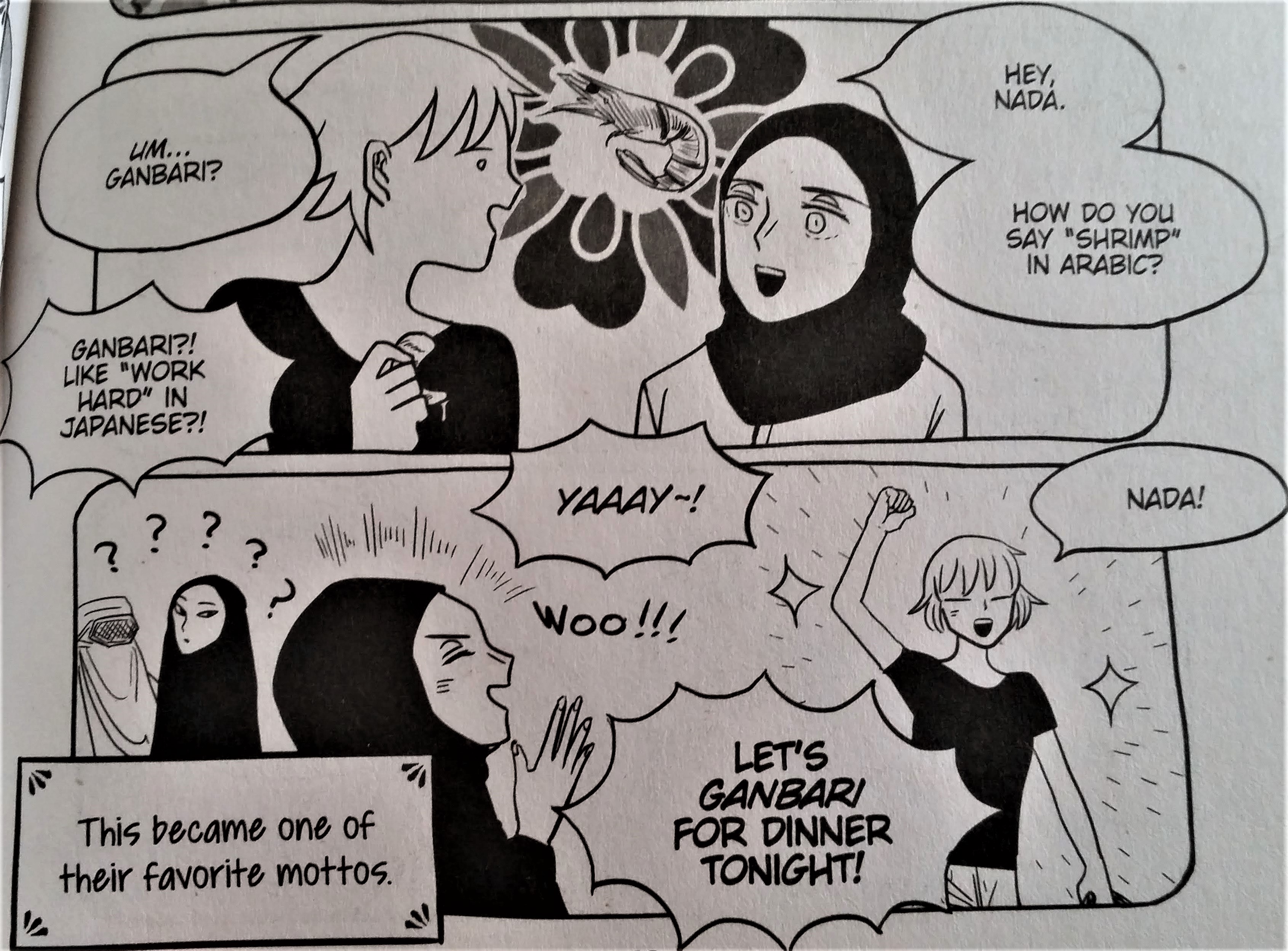

Though it is implied that the narrative is linear, the individual stories are self-contained, acting more as snippets of everyday life than a plot-driven story. Like peering through a keyhole, the reader observes how small, seemingly insignificant moments all add up to a strong, loving friendship between women. In this way, the series has a very realistic approach to relationships and what makes them succeed — the small gestures, the inside jokes, and the shared experiences that build a connection.

While Satoko and Nada is educational in many ways, it is also entertaining. Yupechika has fun referencing memes and playing with words, poking fun in places where it is appropriate and never, ever implying that any one cultural experience is superior. What’s more, it is clear that Satoko and Nada love each other very much; their bond is enviable, growing and evolving with each passing column. This series, which is currently comprised of two English-language volumes available from Seven Seas Entertainment, is a beautiful ode to how fulfilling one’s life can be when one chooses to be open to difference. Satoko and Nada don’t ask the reader to be color- or culture-blind, but to embrace and exchange in the interest of finding common ground. And that common ground is more easily accessible than one might imagine.

Essentially, Satoko and Nada is truly wholesome. It’s a feel-good manga for people who want to remember that there is still some good in the world, that there are still people who meet and love each other in a time so full of divisiveness based on perceived inferiorities. And it seems especially important that it has been translated into English, for American readers especially to read and contemplate. It is a salve to the constant barrage of horrifying news, appropriate for all ages, genders, and creeds, and hopefully an inspiration to fans to move outside their cultural bubble and experience something new.