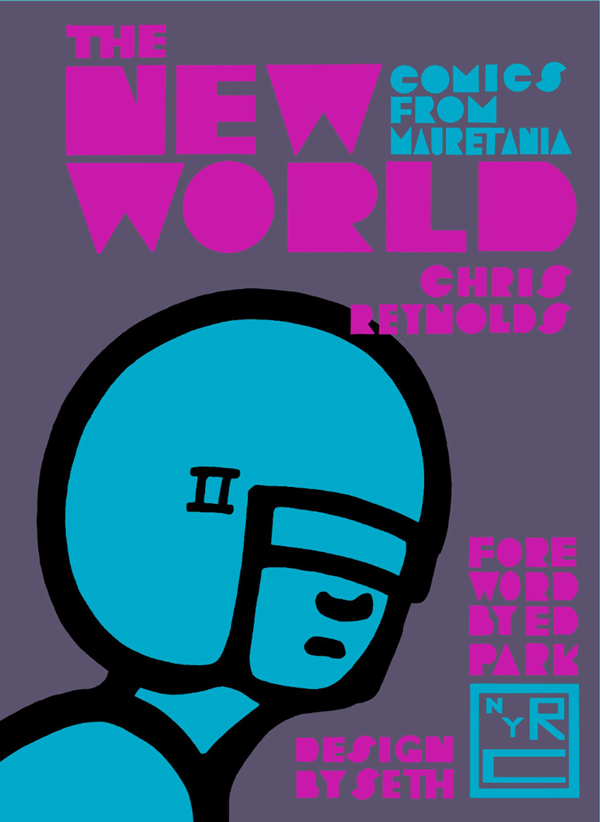

Subtitled “Comics from Mauretania,” the stories in Chris Reynolds’ The New World don’t take place in the African country of the same name, but in some cryptic landscape never referenced by name in the comics to which the title applies, but which creates a tone that unifies the stories, as well as offers some vague sense of place. Like using Brazil as the title for the movie Brazil.

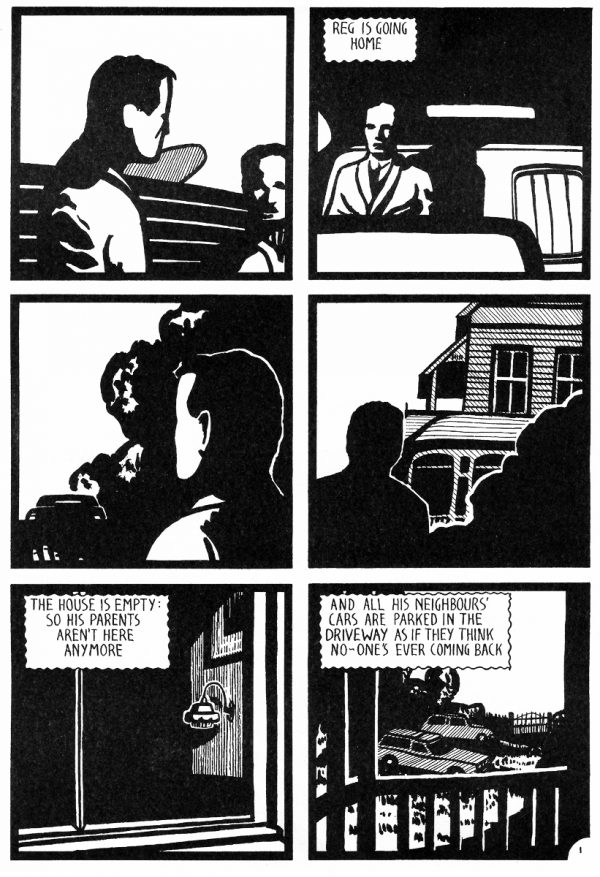

Given such an intangible quality to the unifier of the works, it seems a bit obvious for me to proclaim that the opening story, “The Dial,” is dream-like. Of course, it is. In it, we meet Reg, a fellow of little distinction other than walking through his world baffled at where he is headed, literally like the ball in a pinball machine being pivoted in various directions depending upon how it connects with the obstructions built into the device.

Reg starts out at his parents’ empty home with the purpose of cleaning it out for some reason but is quickly diverted to a long road trip involving a guy named Steve and a mysterious church called the Dial. Reg keeps going over the Dial in his mind even as he is faced with the destruction of his own home, presented as the inevitable result of industriousness and officiousness.

The story completes itself with Reg going over the same conundrums presented in the story in much the same way as any of us, and with its mysteries fading out presenting the finality of a document that outlines the dissipating mysteries in matter-of-fact form. Want to know what the Dial is? Why the house is empty? It explains that and more, though it doesn’t make anything clear.

Kind of like the real world, actually — the more information you get, the less stable everything seems.

The second section in this collection features shorter works, most of them about Monitor, who wears a big motorcycle helmet and visor, a jumpsuit, and a box-like backpack that looks like something an astronaut would wear. Monitor’s motivations are a mystery and his movements even more so.

The various episodes appear unconnected beyond Monitor’s constant searching and consistent disorientation. He never seems totally comfortable in whatever situation he is in, and they often involve his efforts to decipher a situation or a physical space, frequently giving cryptic clues to events and people in the past.

Monitor seems to move a lot and jump from job to job. He is a perpetual visitor, an eternal alien.

But not all the stories are about Monitor. For instance, “Cinema Detectives” offers an incomplete reunion between occasional partners in detection, Inspector Rockwell and Detective Rosa (both of whom appear in further stories) as they collaborate on a case involving missing buildings. The case baffles Rockwell and by the end of the short piece, seems to be destined always to do so. As with any episode in the collection, the story involves a series of details that only hint at the truth behind the world these characters inhabit, though refuse to give you much to work with.

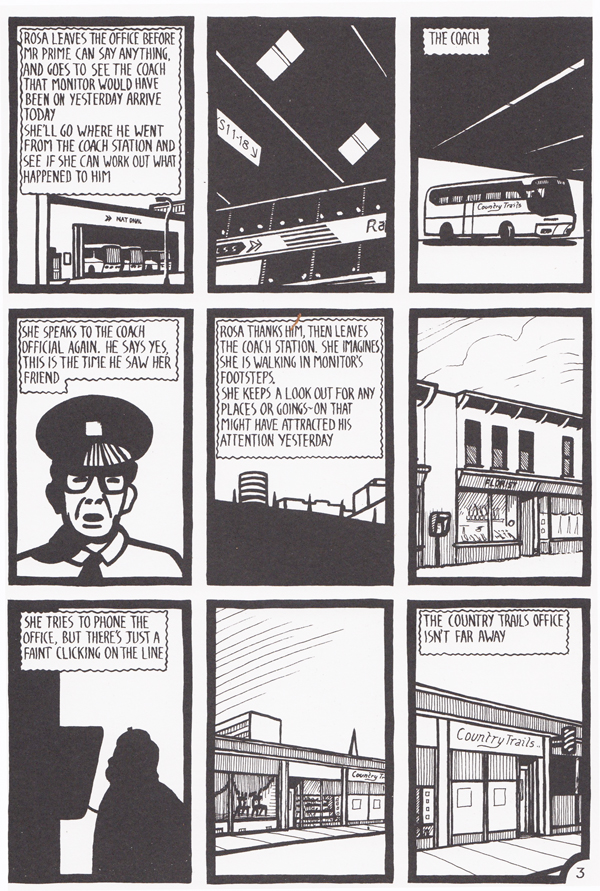

One of my favorites of this section is “We See Each Other,” which is about Rosa and unfolds like a stress dream. Rosa is waiting for Monitor but he never shows up, and her focus on finding him turns into a cryptic odyssey around the city for Rosa, checking into different places and confronting the people in them, and haranguing people in her life to lend a hand in finding Monitor. It’s obvious that Reynolds has realized a world here, and he is giving us a tour of this world, but he’s letting confusion and tension define the world for us.

The next story, “Endless Summer Wells,” offers a calmer, but still similarly dream-like tour of a city. Together they remind me of reoccurring dreams that I have, and I’m sure others must, where I drive to the closest mid-western city I can get to, and it’s always the same place, and in the dream I have been to it before, but each dream it appears new to me despite the fact. That’s the feeling that Reynolds captures, that dream-brain logic and vivid reality where several things are true at once, several opposing feelings are felt at the same time, and it’s this sense of place that begins to weave through the stories, uniting them into one fever dream shared.

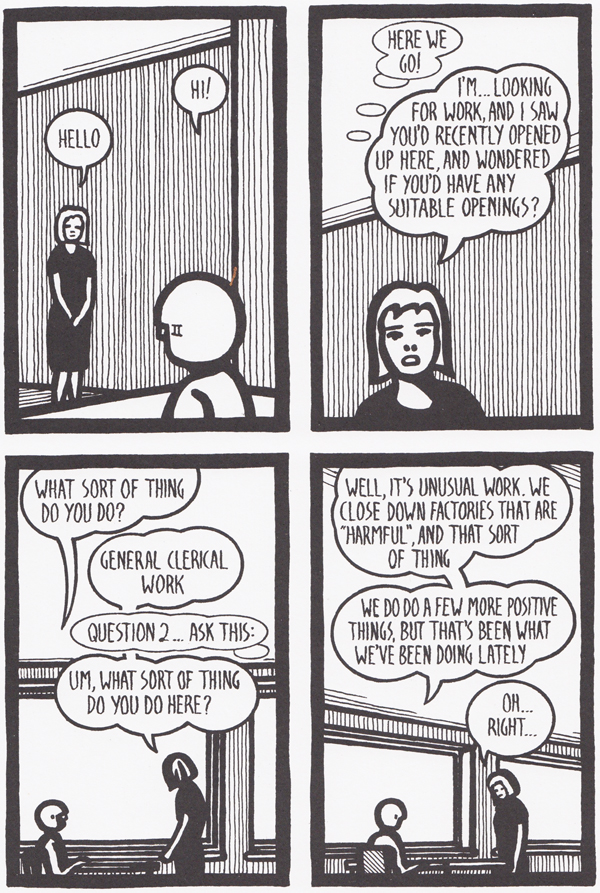

The final section of the book offers the 1990 Penguin graphic novel called Mauretania, which spirals around Jimmy, who was introduced in the short story “Whisper in the Shadows,” in which he donned his own Monitor-like helmet as a kid and expressed his desire to be “Monitor II.” By the time this graphic novel rolls around, he may well have achieved his goal. Now all grown and still in the Monitor helmet, Jimmy runs a mysterious company whose business it is to “close down factories that are ‘harmful’ and that sort of thing,” as he explains.

We find out more about Jimmy and his company — well, sort of — through Susan, who operates kind of like an industrial spy, prodded into finding out more about Jimmy’s business by her new employer, Reynal, who is also pumping her for information about her previous employer. It’s the typical dream journey that we’ve become accustomed to in this volume, with Susan stumbling through a barely comprehensible quest for Jimmy and accumulating information and coming up with conclusions that have no context nor clarity.

In the end, Jimmy, like Monitor before him, seems to have the context and clarity, a circumstance that hints at a status apart from the other characters inhabiting Mauretania, a privileged place that allows him an overview of the complete picture and the opportunity to transgress the limitations that others must adhere to.

In this way, it reads much like a fable of our own existence. Few of us have that massive map of the way things all fit together, let alone have an inkling of the subtle meanings behind mundane actions. We are wandering in the dark, and the mechanisms that are in place take care of themselves while we react to the more obvious movements they make. That’s the rhythm of Mauretania too, and Jimmy isn’t going to launch into exposition because none of us would understand it anyhow. It’s enough that someone else sees the mechanisms from an advantageous vantage point. We can’t all put together the pieces that constitute everything.

Thanks, John!

Comments are closed.