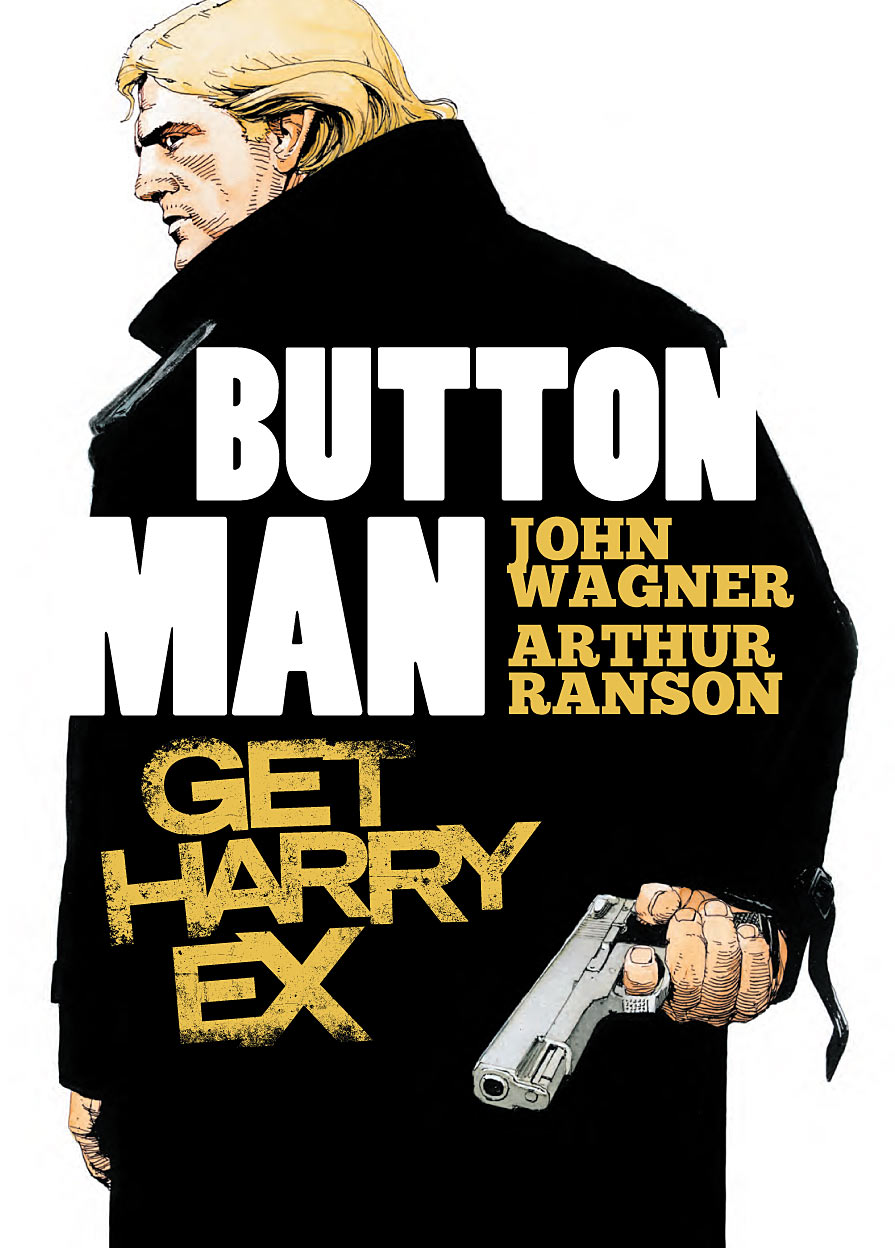

The Button Man series by John Wagner and Arthur Ranson is a rare creature. For a magazine designed to tell fast-paced adventures, this is a far quieter and more subdued piece of work than is typically found in 2000AD, and a reminder of how powerful a writer Wagner can be. A slow-burn story, the series moves methodically and carefully, building up a dangerous environment which wraps up the reader and drags them into engaging directly with the story.

This new edition collects the first three Button Man stories; excluding The Hitman’s Daughter, the fourth volume drawn by Frazer Irving. This is probably a smart move, as much of the book relies upon the naturalistic pencilling of Ranson, whose artwork feels gritty and hard. Rather than go for splash, Ranson repeatedly tones down the violence in the book to great effect – by reducing the bloodshed and emphasising effect, the bullets flying through each of the three volumes have much more of an impact on the reader.

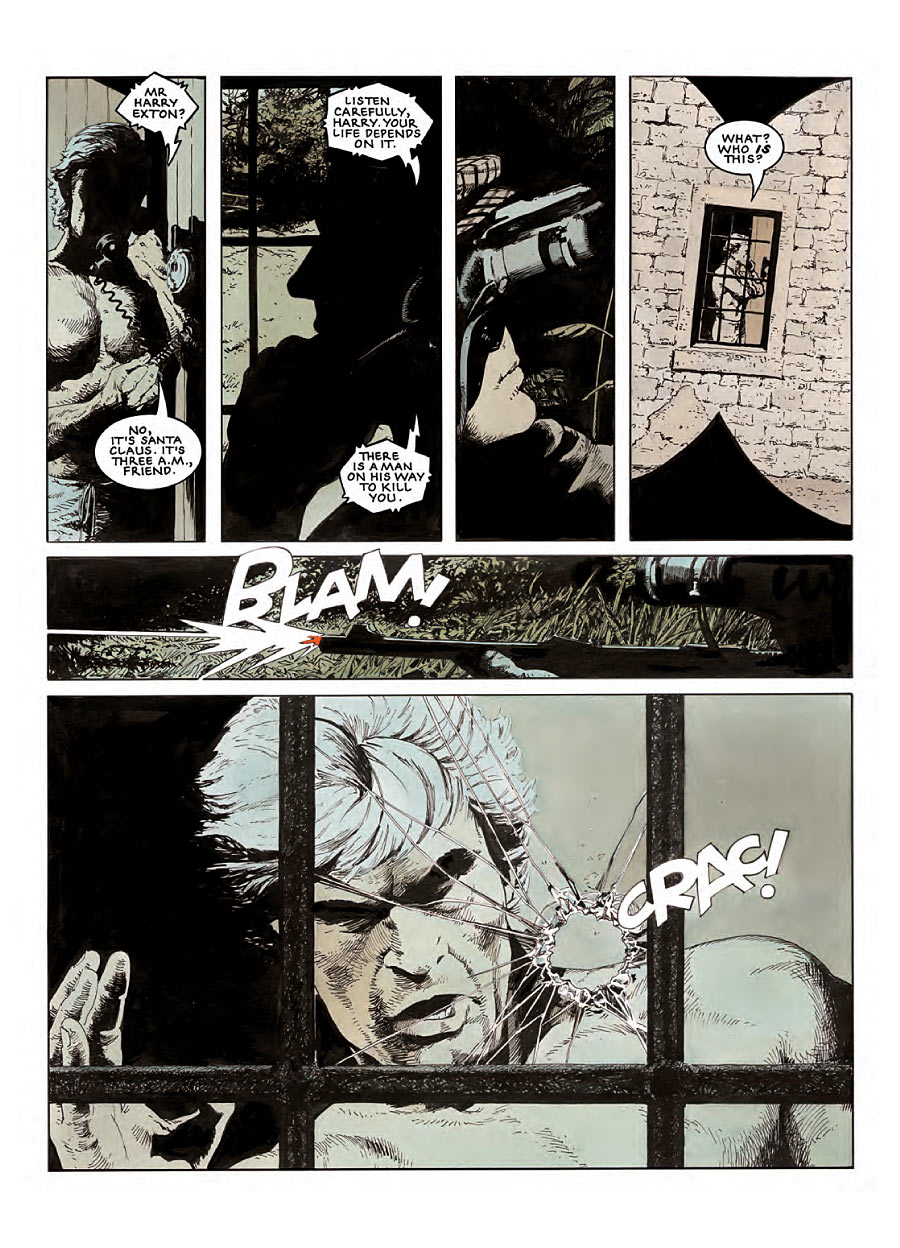

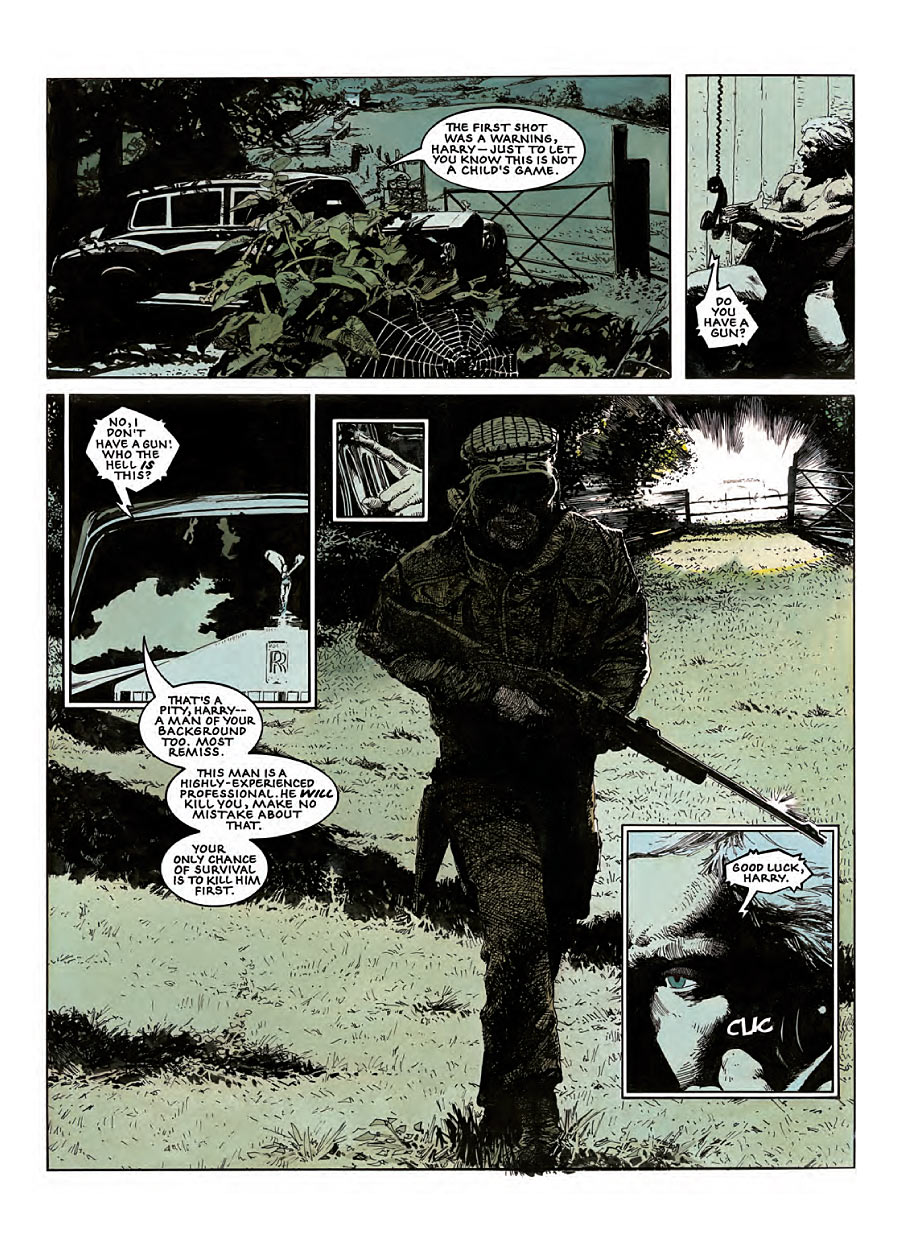

The central premise of the series is one which has become increasingly familiar over the last decade, especially as society grows more in thrall of reality television. Lead character Harry Exton is an ex-mercenary, who returns home to find himself hollowed out by the violence in his past. However, he is then approached by an old friend who introduces him to the concept of ‘The Button Man’. The upper class pit working-class mercenaries against each other in fights to the death, with bets being placed on the winners.

As Harry decides to take part in these underground contests, he then finds that leaving the service is next to impossible, and each book deals with him as he attempts to escape an escalating cycle of violence and conspiracy. The book thereby defines itself as a sustained analogue for the British class system, trapping the poor in a crushing cycle of poverty which can’t be escaped from; all while the rich get richer.

If the story sounds familiar to the premise of stories like Battle Royale – that’s because it certainly does share distinct similarities with those stories. In his introduction, Ranson even discusses how recent films have followed this general concept. But the difference here is in the execution of the satire. Button Man is for Battle Royale as Unforgiven was for the entire Western genre. It’s a redefinition of the entire concept, and stands as some of Wagner’s best satirical writing.

The three volumes here repeat the premise fairly openly, with the only difference being that the pressure escalates each time round. The first volume sees Exton dealing with a series of one-to-one fights in the UK, emphasising the barbarism and personal nature of each murder he commits. Wagner begins by taking his scarred lead character and forcing him into a direct repetition of his past life as a killer-for-hire – only this time there’s even less point in the murders.

As the book continues, the story moves from the UK to the USA, where the battles become more of an exploitative entertainment. Mass battles are waged between groups of Button Men, with the people in power watching the fights from a distance. Whereas the first volume keeps things personal and gritty for Exton – but distant and detached for his handler, or ‘voice’ as they’re called in the series – the second volume exuberantly brings everybody together for a more grotesque yet more hollow version of the same event.

The third volume escalates things further once more, trapping the remaining characters in a chase across America, as a hit is put out and a score of Button Men are sent to try and collect. Each volume tells a complete and satisfying story, but the surprise here is how worrying it is to complete one volume and then know you have to move onto the next. There’s a palpable feeling of tension and fear before starting each new story, knowing that the characters are going to get trapped once more in this endless cycle of pointless violence.

The most remarkable aspect to this collection is how little it feels like a 2000AD product. Ranson’s art is low-key and quiet, evoking the mood of revenge-thrillers such as Get Carter. Britain is presented as a light and airy space, with almost every page having at least one panel which snaps away from the characters to show us the terrain they’re standing in. This creates the idea that somebody is always watching, as well as allows the reader an opportunity to get a handle on where the scene is currently set. When the time comes for a fight sequence, this use of page space means Ranson can orientate the readers on how the characters are situated and which space the combatants have to move within.

This means we aren’t lost once the shooting begins, but instead can build up an immediate visual image of how battle will likely go, who has the upper hand, and how the opposing tactics are being employed. It gives the reader a chance to look into the heart of the battle and work out what’s happening without Wagner needed to exposit at length.

Wagner’s script is light, which also assists the reader greatly. By having only a minimal amount of dialogue – Exton himself is relatively humourless, and remains calmly and ruthlessly professional during the series – more emphasis is placed on the actions of the characters. Each slight movement is carefully documented by the creative team, forcing a deliberate pace over proceedings. Even the fight scenes are slowly played out (although less so during the second and third volumes, where spectacle becomes more important to the story), forcing the reader to slowly experience the murders as they happen.

The central allegory within the story does sometimes grow a little overwrought. Each volume tends to show one sequence where animals are portrayed as signifiers for the main characters, and engage in heavily symbolic engagements with one another. At one point, for example, a badger is slowly approached by a snake, before suddenly revealing claws and killing the creature unexpectedly. This is a little on the nose, but is at least an indulgence which doesn’t telegraph the ending.

Wagner also has a few problems with the central character. Exton remains fairly untouchable throughout the story, and despite spending most of our time with him his narration remains sparse and factual. He tends to simply state what is happening to him, rather than respond in any emotional way. This gives him a fairly strong amount of grit as a figure, but it also results in a protagonist who purposely remains unrelatable.

There are a few signs of wear, given that the first story was released in 1992, but for the most part this doesn’t feel too dated. The lettering is the most notable improvement over the course of the collection, with Ellie De Ville’s handling of the final story featuring a markedly stronger sense of itself. The fashion and design doesn’t really stand out as feeling like it was drawn twenty years ago; while Wagner’s style of dialogue and script doesn’t particularly change between the stories told in 1992/1994 and then the huge gap before 2001’s third volume.

The scripting grows wordier, perhaps, in the final volume of this collection, but for the most part Exton remains the same half-responsive force of nature he started as. This is perhaps best demonstrated by the very last page, which works best really as a definitive final statement that people can’t change their nature. The characters in this series are all impacted upon heavily by the nature of their birth – those born into money stay in power, those born away from money do all the work. There’s never any particular idea that people can change from that, and the characters all seem stuck in their position in society, despite Harry’s rise up the social ladder.

It’s a gripping collection of stories, with some intriguing and subtly-threaded subtext weaving through every page of each volume. Enthralling told by Ranson, and with an understated and smart script from Wagner, it’s thoroughly involving and enjoyable.

Button Man: Get Harry Ex collects the first three volumes of the series, and was released on Wednesday.

” how little it feels like a 2000AD product”

I believe this strip was originally created to appear in the (ultimately) short-lived Toxic magazine; as a 2000AD strip it’s one of the few in which the creators own the rights.

Now a possible television series with Bad Robot

details – http://www.arthurranson.com/blog/tv-button-man

Comments are closed.