In Guillaume Singelin’s PTSD, a fictional war and a fictional city bear resemblance to real life, examining in dark and gritty terms how people are stripped of their connection with other humans, and the daunting work of rebuilding what they lost.

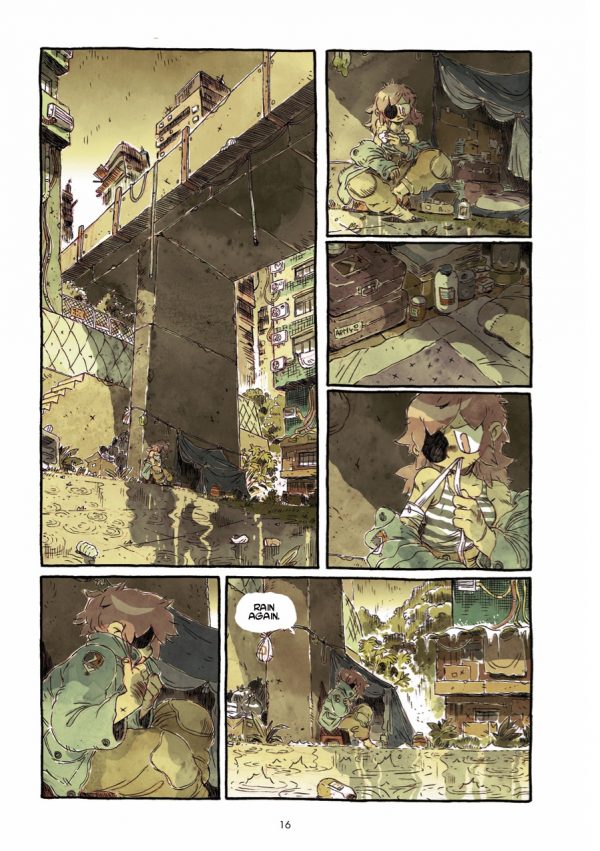

Jun is a homeless veteran who staggers through a chaotic and filthy urban environment on the constant brink of further breakdown, dependent on pills and solitude to keep her pain away. While on combat duty, Jun lays awake in her tent, the surrounding bombs booming through her skull and rattling her awake. Her current predicament is fully haunted by her rattled past.

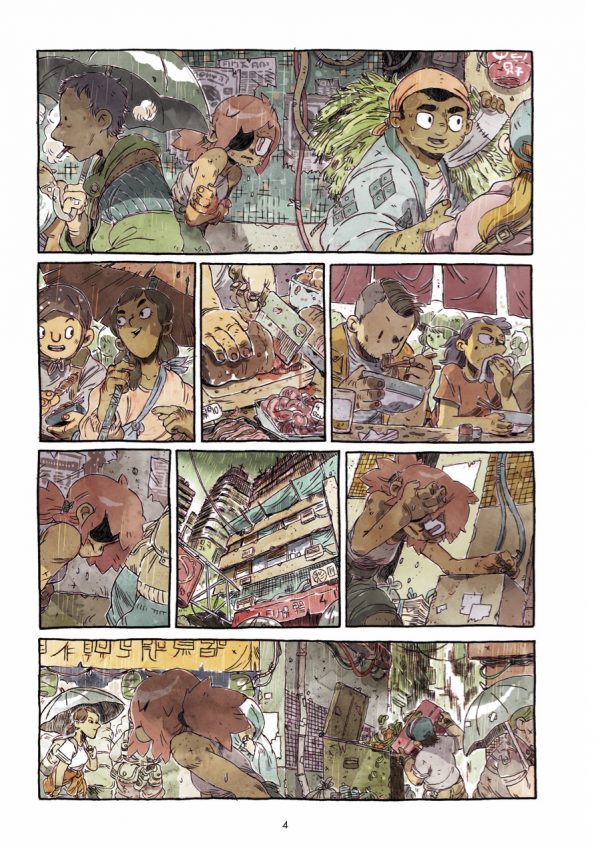

A morning encounter with Leona and her son Bao leads to an offer of breakfast after Jun passes out in front of their food stand. Leona, a single mother who’s struggling to keep her new business afloat, begins the complicated and messy process of attempting to befriend Jun, who resists attempts at closeness and lashes out at honest concern while escaping back into a life of violence and despair.

“How can we go back to being who we were before? And what are we now?” asks one homeless veteran in the story.

This loss of identity is entrenched in the soldiers’ perception of being part of a team and the shattering of that image following a war, where it becomes every person for themselves, though some of the homeless try to change that. It’s also part of something a pair of sleazeballs say to Jun — that soldiers were taken care of by the government. Her response is to rage against them about the fate of ex-soldiers, and yet, the truth is somewhere in-between. Soldiers were taken care of by the government during wartime, in exchange for their risk. Sending them into that situation created intense community. And that community was fractured after serving. The “we” the soldiers can’t reclaim isn’t an individual one, but a collective one. They were a community that no longer exists.

Saving yourself is one challenge, but fashioning connections to create a new “we” is quite something else, and a particularly difficult task when the self is broken, the ability to make connections impaired.

And the danger of the street has created a dog-eat-dog backdrop, one fueled by drugs and violence. Drugs to cope and violence to accompany the trafficking of the drugs, which creates an atmosphere of distrust that is taken advantage of by gangs who persecute the homeless veterans.

It’s Leona who might just be the non-shattered self who can gather a community from these damaged bits, but the dangers of the street and the demons of the veterans threaten to upend any compassionate effort and create such tumultuous animosity that the veterans may not ever be able to come together.

There are plenty of characters in this story, but one of the main ones, thanks to Singelin’s detailed rendering, is the city itself. Inspired by Tokyo, it’s a cluttered urban landscape of nooks and crannies, crowded and filled with life, with people in despair taking refuge in whatever corners are available. The city’s clutter is purposeful — it’s unattainable needs crammed together — food, companionship — taunting the homeless by being so in their reach, but which they are so obstructed from grasping.

It’s really a rendering of the mental state of Jun that Singelin creates in his city. Cluttered, hard to find focus, filled with fleeting moments and lost opportunities, as well as encroaching dangers and destructive distractions. In the end, PTSD ends up being a hopeful work that calls for blind compassion, and a mix of communal healing and self-sufficiency.

Comments are closed.