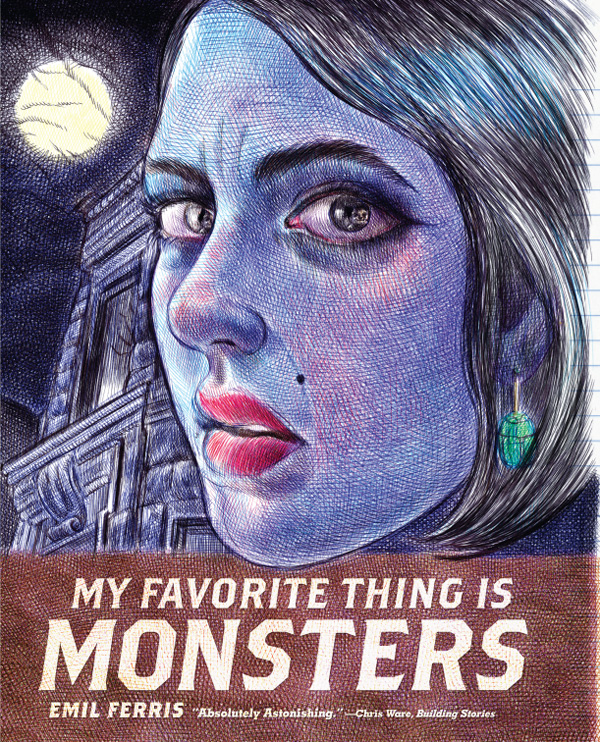

It’s fair to say that Emil Ferris’ sprawling My Favorite Thing Is Monsters — volume one of a two volume work — came out of absolutely nowhere for many people. Ferris is a Chicago-based artist who had worked in illustration and toy design, but after a debilitating battle with West Nile Virus, went back to art school and redirected her energy to this graphic novel that reads like a memoir, though my understanding is that it is at best based on her childhood, with a biography hidden inside. It’s her first graphic novel and given the reception, not her last, and you can only hope that the quality that makes this book so mesmerizing — simply put, that of an energetic outsider — is retained.

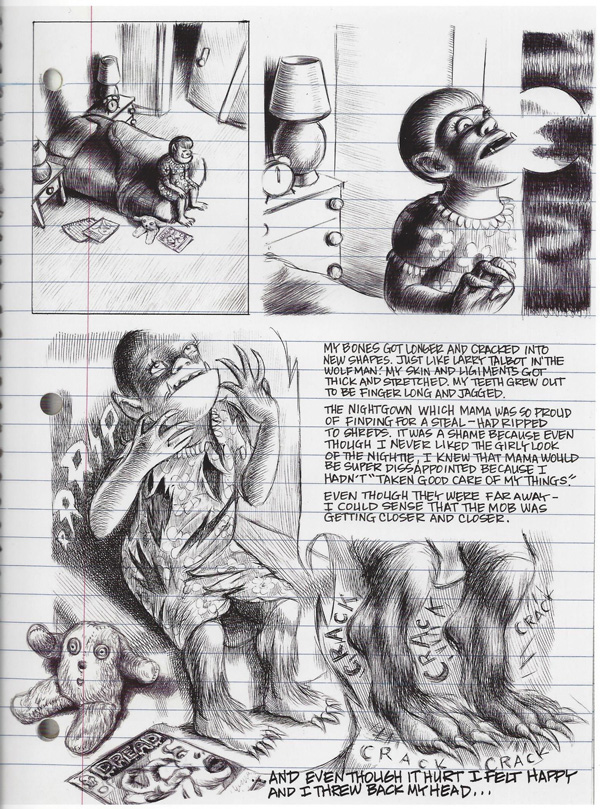

So sprawling is Ferris’ book that it’s actually hard to pin down the story in any satisfying way — that is, a way that actually captures what the book is about. On the surface, it’s a monologue by young Karen Reyes, obsessed with monster movies and visualizing herself as a werewolf girl in order to rationalize the difference in her that the world perceives and acts on. She is struggling with her sexuality at a time she is only just becoming aware it even exists, and as she creeps into the world of adults, is also become more clearly aware of the lives of her older brother, Deeze, and her mother.

But that makes the book sound awfully basic, and it’s anything but. In covering the intricacies of her day-to-day life, you are not only party to the inner workings of Karen’s mind, fumbling alongside her to interpret what in the world all this reality really means, you are also sucked into the her mysterious, almost conspiratorial view of the small world around her. This sees Karen giving back stories to neighbors and attaching mysteries to their lives that demand she solve them, including some that wrap around her brother and her mother.

Most especially the mystery focuses on the death of her neighbor Anka Silverberg, and the unexpected opportunity to really explore Anka’s past, which allows Ferris to devote a good-sized chunk of Karen’s story to the retelling of Anka’s. Hers was a dark and traumatic life of exploitation in Nazi Germany that by contrast makes Karen’s look self-pitying. But Anka’s story also makes plain that darkness is darkness, it wraps around you wherever it chooses — Nazi Germany or 1960s Chicago — and the real measure of the person is not the real level of trauma endured, but the way the situation is approached by that person, how well they rally to survive and learn.

But even then, Ferris’ story takes little twists and turns, not always just in plot, but also in focus, as with the time spent visiting the art museum with Karen and Deeze, learning not only about the characters’ relationships with art, but about the art itself as dissected through the mind of Karen. But there are also odd details about Karen’s friends, about various neighbors and people she meets, like the hippies who give her hash brownies, as well as the genuine touching drama that involves dealing with loss in general, whether mythic, whether sudden and mysterious, whether drawn out and painful.

Wrapped up in all this is an examination of self-esteem, of the way women are expected to conduct themselves, of how they are viewed by the men around them, what those men need from them in order to feel whole themselves, and the strange, exhausting psychological landscape women might inhabit because of this dynamic.

It’s sprawling, as I said, but it’s also dense. It’s packed, in fact, more packed than most graphic novels you encounter — packed with ideas and plots and words and pictures, creating some of the most dense, intentionally cluttered comics pages I’ve ever seen. And that’s where the energetic outsider quality I mentioned comes in, and really works to the book’s strength.

For one, it’s all ballpoint pen drawings on lined paper — color sections drift in and out of the narrative, though most of it is black and white — and that gives it the quality of something you’d find in a notebook in someone’s attic somewhere. But also the content leaves the same impression. Packed with details of life and long strands of emotional brain wanderings, illusory perceptions, and excited personal mythology, whether real or imagined, it reads in part like exactly the sort of autobiographical manifesto you would find in that notebook hidden in the attic.

This is the best part of Ferris’ work, the news that it gives — comics are still weird, still home to the weird storytellers with their weird stories that don’t belong anywhere else, stories that are so entirely their own that they can seem like personal manifestos in hidden notebooks. We might live in a world that has seen graphic novels sold in mainstream bookstores and covered in the New York Times, where it has become more desirable for young people to pursue them as an art form, but My Favorite Thing Is Monsters reveals that it is still the form for outsiders after all — or as Ferris puts it, a place for a “a good monster” who “sometimes gives somebody a fright because they’re weird looking and fangy,” in which case, the story of Karen Reyes speaks to many of us.