So dire has the world situation been, even on the smallest levels, that the massacre of the Charlie Hebdo staff seems like it happened at least a decade ago. But it’s only been three-and-a-half years and there’s been much blood under the bridge since that has elongated our perception of time. That’s a privilege that I and many others have, that by not being direct victims of such horror and by having recurring opportunity to tune out of the barrage of nightmares that are reported, I can put the worst moments in the world at a distance in order to save my own sanity.

But to those who are there, an eternal present can haunt them, indeed torture them, and the path to escape that psychological prison is not an obvious one.

That’s what French cartoonist Catherine Meurisse documents in her memoir Lightness, which depicts her emotional state following the Charlie Hebdo murders and her efforts to deal with what she witnessed. Meurisse arrived late to work one day to witness the two gunmen fleeing from the office, and taking refuge in the theater next door where she and others had to process what had just happened.

The processing didn’t end with that day and it certainly doesn’t end with this graphic novel. Meurisse makes that plain as she shows how the minutiae of reality bring back reminders of what transpired, the little details that stick in her mind spurred on by innocuous words spoken that the speaker could never know makes such a mark in her psyche.

Aside from the trauma, Meurisse also shows how the nuts and bolts of being a survivor of such an incident affects the way you encounter the world, specifically in her case with a constant police escort to protect her should further attempts be made. Her guards become the ghosts of the horrible scene, accompanying her everywhere and reminding her of what happened. They are the manifestation of the emotional and psychological weight that bears down on her.

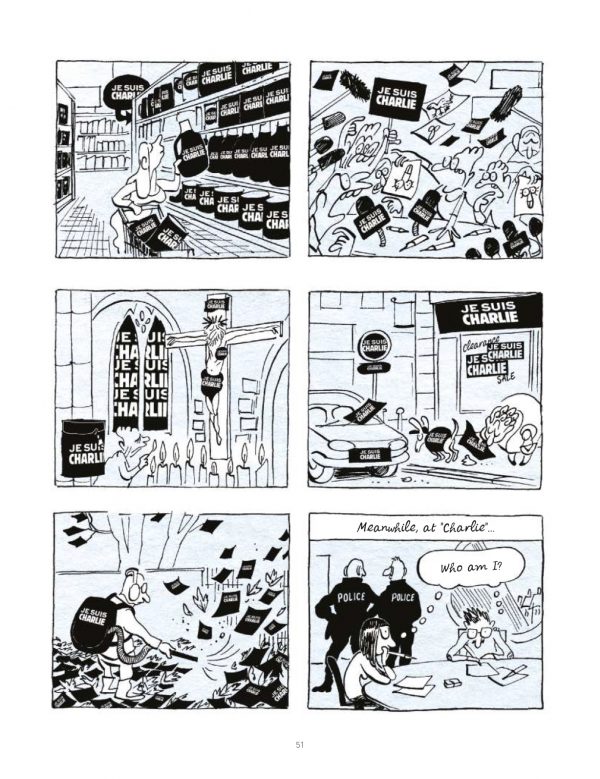

Another unexpected burden that Meurisse must grapple with is the idea that the tragedy quickly belongs to everyone, that it becomes a symbol of wider issues and even a personal matter to those with no involvement. How do you grieve when the focus of your grief becomes co-opted?

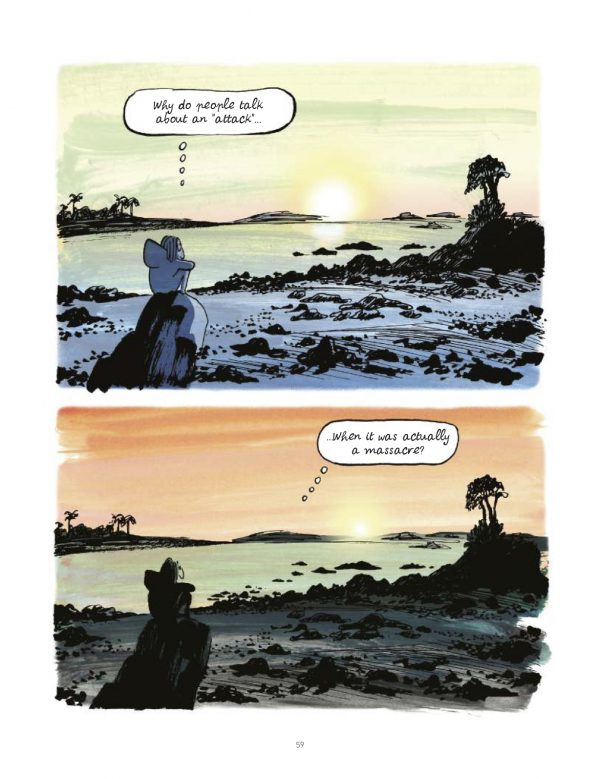

Eventually, Meurisse decides that the only way for her to heal is to step outside the world that was so throttled by horror and into a more bucolic setting that allows her to let her mind become awash in art history. It’s there that she makes further connections between the circumstances of art history and the work of Charlie Hebdo, and the subject matter of that history and its place as a slice of never-ending horror that moved into the Charlie Hebdo murders and then past it, into further, nightmarish incidents.

Meurisse’s conclusion is the only one that anyone could ever have — grasping for the light, even in the smallest portions, in order to cast away the darkness as best she can — but that’s partially the point of her challenge. Part of the job of a Charlie Hebdo cartoonist is to face the darkness, react to the darkness, depict the darkness, challenge the darkness, interpret the darkness, embrace the darkness. And that’s hard to do when you have to escape the darkness.

Part of the purpose of Lightness is to explore Meurisse’s relationship to darkness in the context of her trauma, of her extreme sense of loss. She does that with a Charlie Hebdo sensibility that no doubt comes naturally to her after a decade in those offices. She jokes about the murders and the murderers, about the victims, about the larger implications of the incident. She speaks to the dead and these conversations aren’t somber. She is coping.

Darkness is a coping mechanism, as many of us know, but it is balanced by light. We need both of those to heal, though neither may heal us permanently. It’s really amazing to me that Meurisse can share not only a story that is very personal, very revealing, very raw, but does so in a way that puts her right out there, vulnerable. I admire her for being able to do that so honestly.