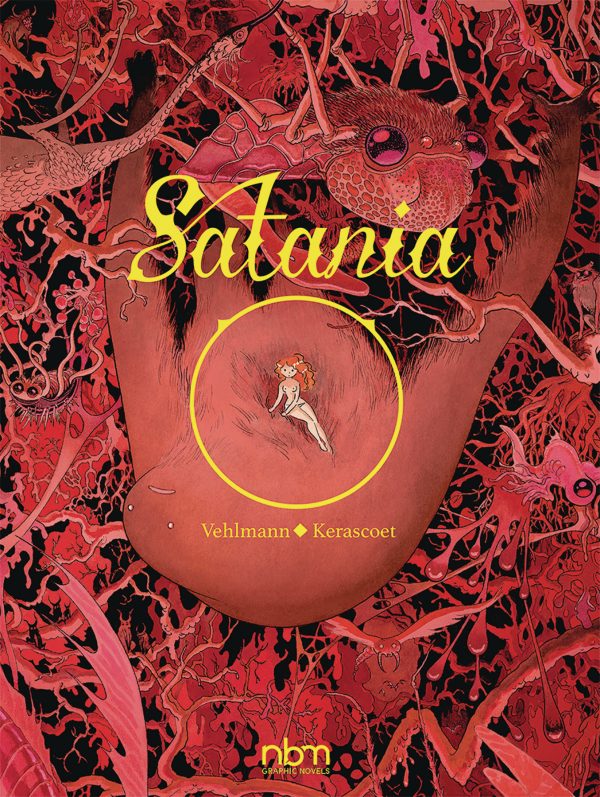

There’s something delightfully old fashioned about Satania, at least at the beginning, and that nod to tradition is what makes the whole experience so thrilling the nostalgia for this kind of adventure tale is slowly peeled away to reveal something more mysterious and terrifying.

Completely different in tone than Fabian Vehlmann and Kerascoet’s previous achievement, Beautiful Darkness, this story evokes Jules Verne and Journey to the Center of the Earth before careening into Lovecraftian chambers, though listing those narrative touchpoints makes it sound more standard than it is.

A team of researchers are exploring a cave in order to prove that Hell really exists — that is, there is a place with real inhabitants that has inspired our legends. The scientist behind this theory, Christopher, has even wrangled the Theory of Evolution into a form that supports his ideas. But Christopher has disappeared into the deeper caverns of the site, though his team labors on.

When circumstances force the team to move further underground, the players become more distinct, particularly Christopher’s sister, Charlie, who wants to find her brother and prove his ideas to be true. Fulfilling the role of skeptic is Father Monsore, a priest who tries to get the team to evacuate before they lose their lives, and who scoffs at both Christopher’s fantastical notions and the very idea that he could have survived in the deeper caverns.

It’s very much a journey into the heart of darkness — darkness being contained within the hidden bunkers of our own world — that as with Conrad’s tale involves the stripping away of civilization and rationality. At the same time, it’s not a descent into madness exactly — those capable of survival will not be the ones who accept irrationality, but rather shift their concept of the rational to the strange world and the beings who unfold in front of them as they journey deeper.

It’s no spoiler to say that Christopher’s ideas are both right and wrong. Satania’s great strength is that it provides adventure and visual spectacle on a scale and with an energy that isn’t often achieved with such technical prowess in comics, while still maintaining a portion of mystery that hangs through the story like the fog. There are never so many answers that the sparks of the story become dulled. And the cramped intimacy is never sacrificed to the bombastic moments.

And in the character of Charlie, there’s a female protagonist to inspire all readers. Kind but ferocious, Charlie has the same agency any reader would desire in her situation, and this is ultimately her story. The revelations of her journey tell us less about any wider truth, more personal ones that we can take comfort in. Charlie in Hell seems like an amazing person to be.