By Gabriel Serrano Denis

One cannot venture into the world of anime and Japanese art without coming across the names of Yoshitaka Amano and Mamoru Oshii. Their individual influences on modern art and filmmaking are so widespread that their only collaboration, the 1985 direct-to-video animation Angel’s Egg, is so difficult to find that it remains as elusive as the film’s own challenging narrative.

Amano’s work as a character and conceptual designer on early anime series, as well as his work on the popular Vampire Hunter D book series by Hideyuki Kikuchi and the early Final Fantasy video games, have cemented his reputation as one of the most recognizable and influential artists in Japanese popular culture. Oshii, director of the groundbreaking cyberpunk film Ghost in the Shell and its sequel, Ghost in the Shell: Innocence (the first and only anime film to screen in competition at the Cannes Film Festival), equals Amano in sheer ambition and influence in both Japan and the West.

Agreeing to work together after both had worked extensively in the animation industry,

Oshii and Amano set out to make something for themselves. The result was Angel’s Egg, a woefully underseen work that overflows with the talent of both artists, showcasing a unique world and narrative that remains fresh and potent to this day.

Oshii and Amano set out to make something for themselves. The result was Angel’s Egg, a woefully underseen work that overflows with the talent of both artists, showcasing a unique world and narrative that remains fresh and potent to this day.

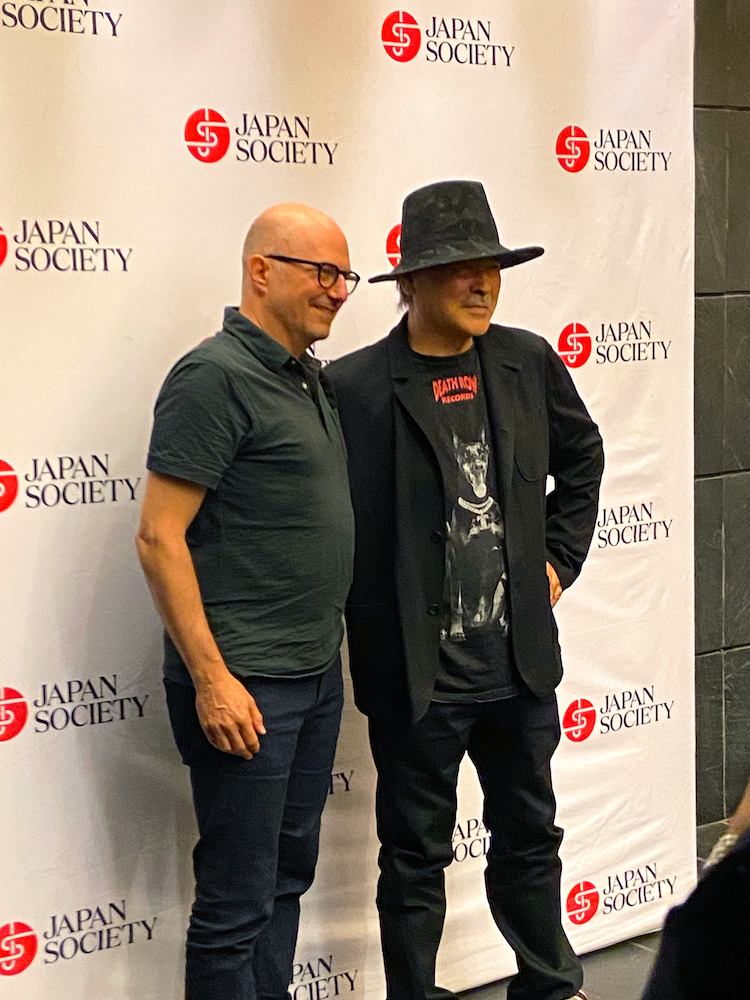

Presented at the Japan Society in New York City in conjunction with the Lomex Gallery’s exhibition showcasing Yoshitaka Amano’s new and historical works, The Birth of Myth, the screening was a rare opportunity to not only watch the film but to experience it on a large screen alongside many others in search of this animated treasure. This is significant as the film was produced as an OVA, and thus only made it to Japanese audiences by way of VHS tapes. Though catching the film in any format is a boon, watching it in a theater was without a doubt the most immersive and ideal way to experience it.

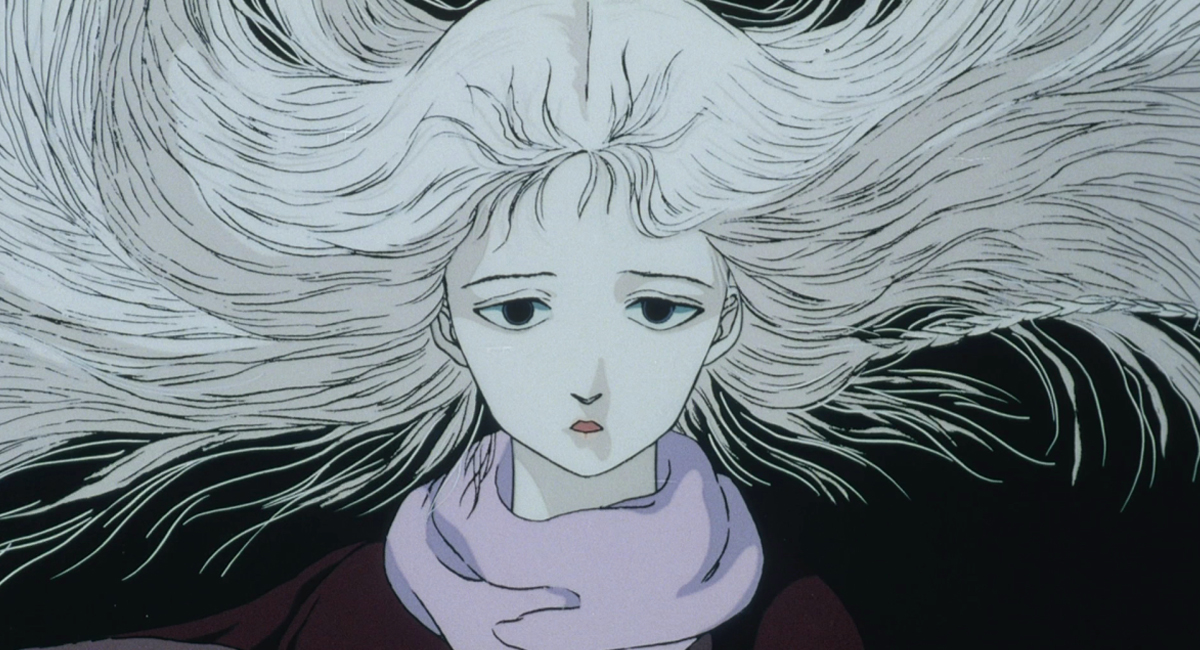

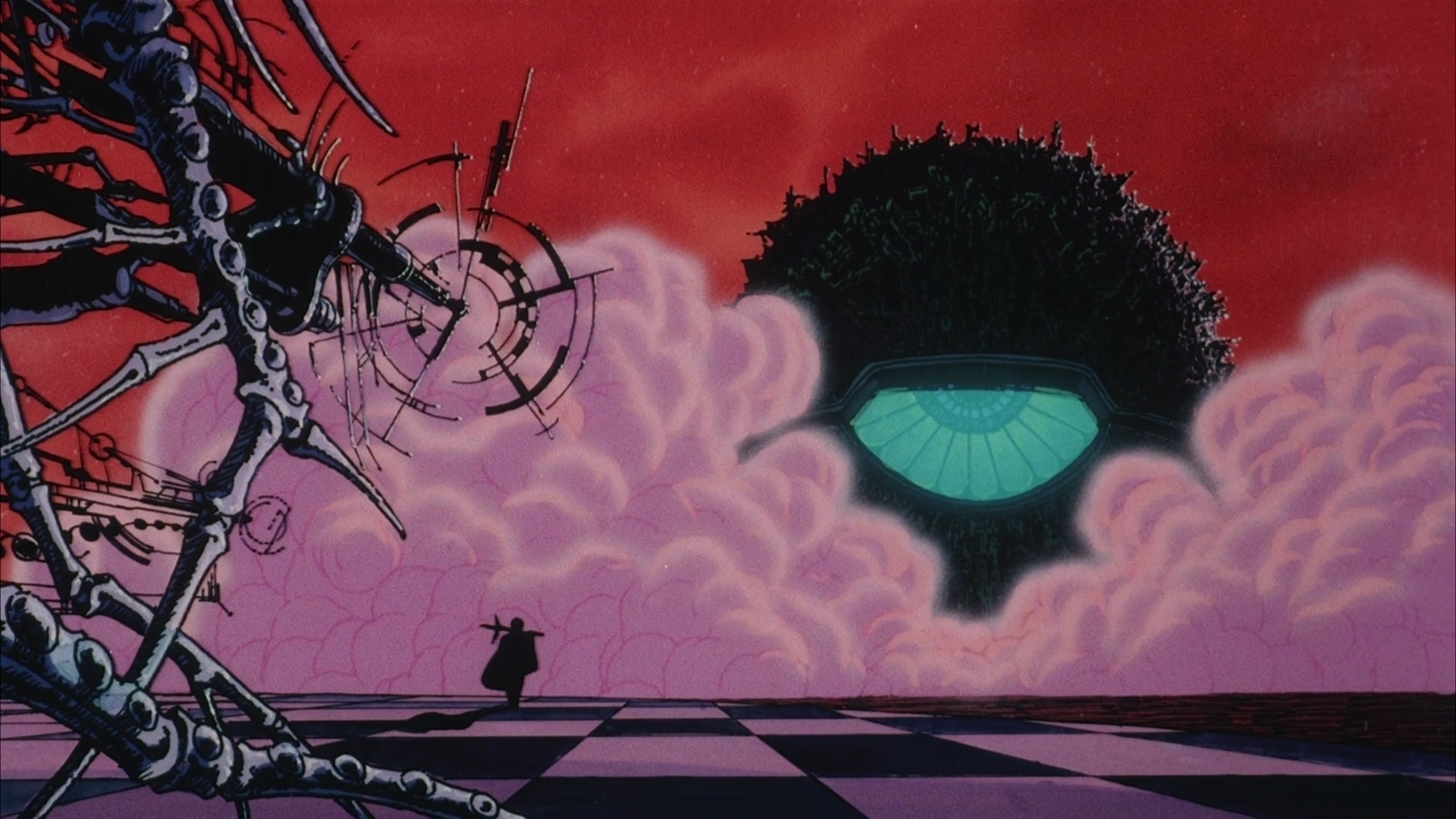

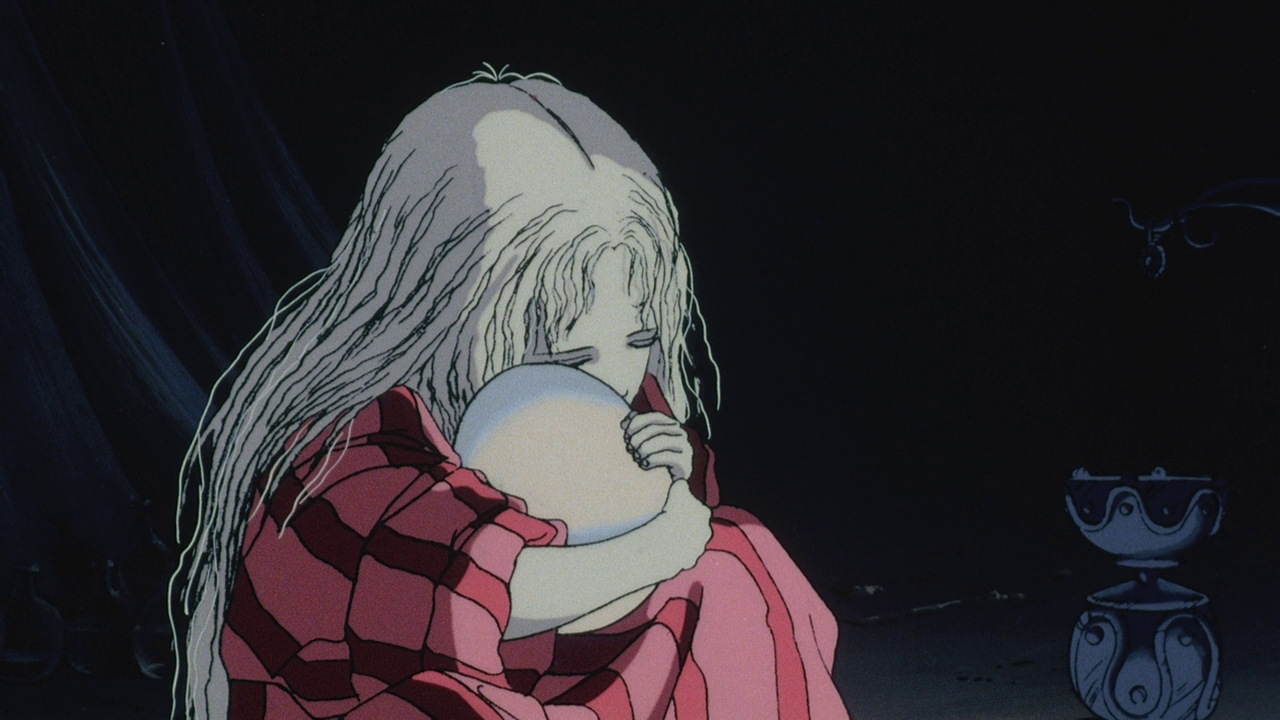

More of a piece of visual art than what was expected from anime in the ‘80s, the film follows a young girl carrying an egg through a vast and desolate dystopian landscape, her motivations for protecting the egg cryptically revealed through the sparse moments of dialogue that cut through the silence and striking imagery. Images of biomechanical machinery crossing an empty city street, spires with transparent eggs that reveal

large birds in an embryonic state, a gigantic ship in the shape of an eye composed of several chrome statues, and men throwing spears at the shadows of large fish roaming the city streets are mainly what the make up the fabric of the 71 minutes of this moving piece of art. Throughout all this, a man with a mechanical sword follows the young girl, finding her at every twist and turn despite her attempts to outrun him. Is he a protector or a

destroyer?

large birds in an embryonic state, a gigantic ship in the shape of an eye composed of several chrome statues, and men throwing spears at the shadows of large fish roaming the city streets are mainly what the make up the fabric of the 71 minutes of this moving piece of art. Throughout all this, a man with a mechanical sword follows the young girl, finding her at every twist and turn despite her attempts to outrun him. Is he a protector or a

destroyer?

This small piece of tension and suspicion is the only thing in the way of drama the film proposes—the main purpose of the film lives in its expressionistic imagery and operatic score. As such, the film asks a lot of patience from the audience, but it isn’t without its rewards. Much like the films of David Lynch, Angel’s Egg builds its own world and dream logic to guide us through its unique journey. The images build towards an interpretation of a world destroyed by the folly of man, leaving behind the husk of a society where the task of protecting an egg feels like the most important and arduous ordeal for any human.

One trusts that this task is a benevolent one, as the child’s innocence begets our sympathy. But even that is left to interpretation and makes the audience complicit in the mythmaking on display. The viewer builds the puzzle however they see fit, but what is certain is that Oshii and Amano have an interest in challenging notions of destruction and the necessity of hope in the face of annihilation.

Watching the film with an audience was especially rewarding as the film dives between moments of deep silence and ethereal pieces of music that accompany some of the most impressive sequences of animation put to film. Even scenes where the young girl runs and her hair flows and billows against the stark art-nouveau-inspired backgrounds are awe-inspiring. Seeing Amano’s work come to life before one’s eyes is reason enough to go along this difficult journey, but sharing in that silence with an audience and being mutually absorbed by the visuals made this a special occasion for fans who have waited so long to get a proper viewing of the film.

Amano, in attendance for the film’s presentation, was amongst the audience and admitted

to having last watched the film perhaps 10 or even 30 years ago. Even his memories of the film were spotty as he could not remember his precise role in the film, though he could give the approximate number of storyboards he drew for the film (about 300 to 500). Nevertheless, what he remembered of the experience was tinged with nostalgia for a time when he took risks and made a daring film no one understood alongside his

contemporaries. He remembered the people who animated the girl protagonist’s hair by hand, the long hours spent in the studio trying to finish his storyboards, and his admiration for Mamoru Oshii.

to having last watched the film perhaps 10 or even 30 years ago. Even his memories of the film were spotty as he could not remember his precise role in the film, though he could give the approximate number of storyboards he drew for the film (about 300 to 500). Nevertheless, what he remembered of the experience was tinged with nostalgia for a time when he took risks and made a daring film no one understood alongside his

contemporaries. He remembered the people who animated the girl protagonist’s hair by hand, the long hours spent in the studio trying to finish his storyboards, and his admiration for Mamoru Oshii.

Just like the girl running towards an unknown destination for the sake of something grander, for Amano, the journey, though arduous and unyielding, was its own reward.