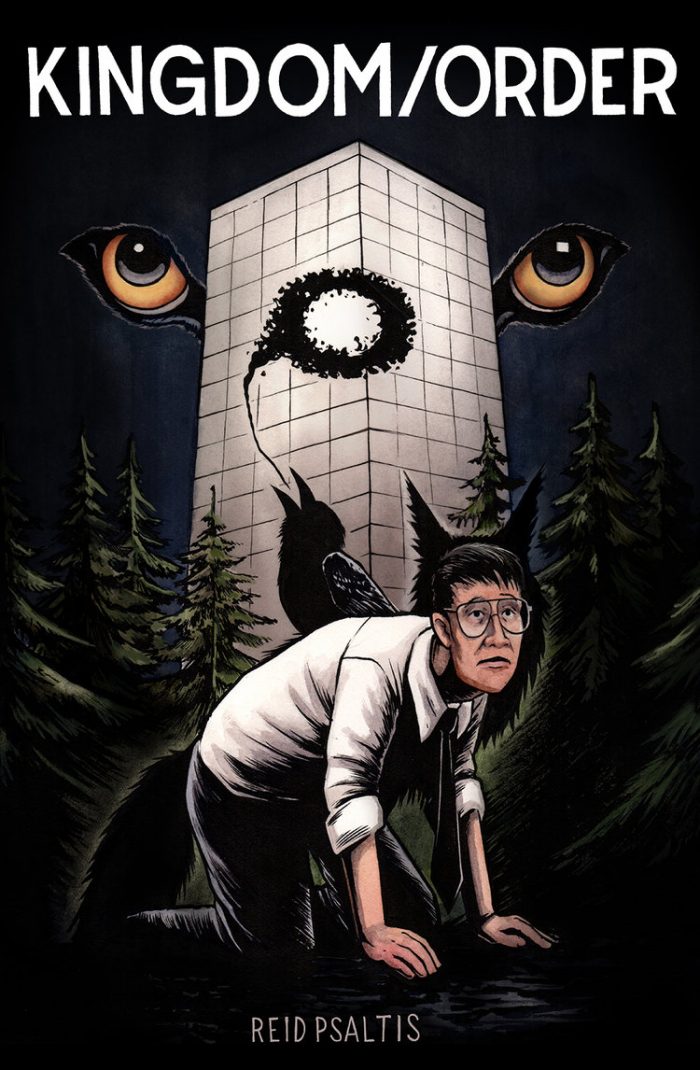

A silent, surreal meditation on the human condition in context of the natural world, Kingdom/Order takes as its hero an unnamed man in an unnamed city and in drawing connections between this urban dweller and the so-called “wild kingdom” finds the commonalities between the two might be largely built on desire.

Reid Psaltis’ meticulous black and white work does well with a wordless story, taking the reader by the hand through the journey and being exacting about what the reader is seeing. Why, however, is a different question.

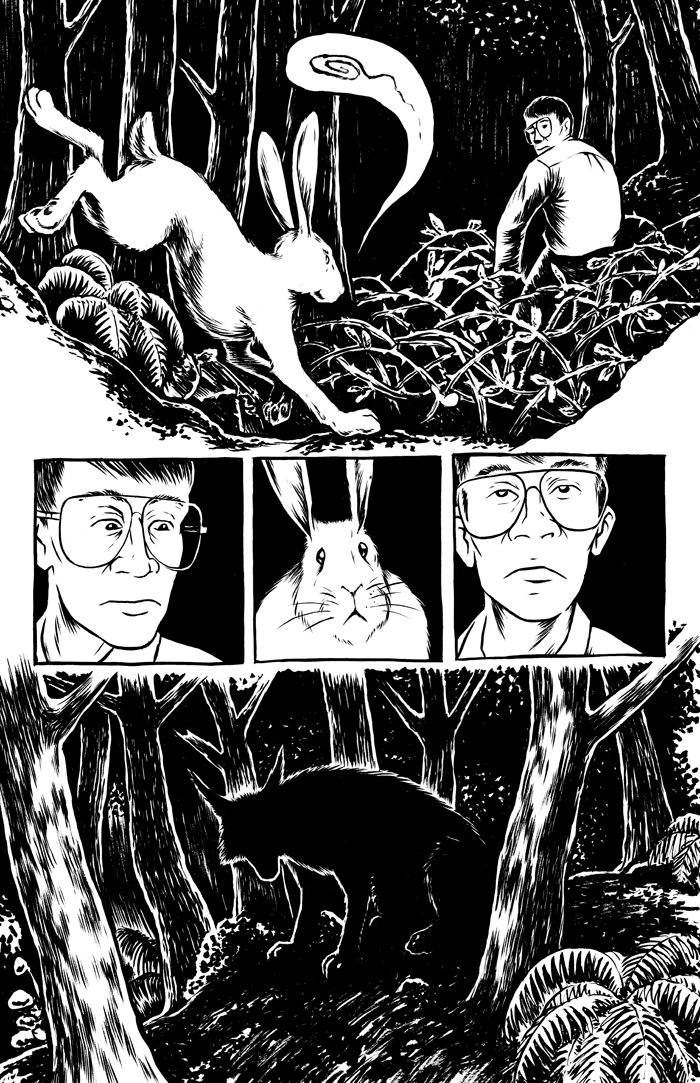

The unnamed man’s meaningless passage through the urban landscape is disrupted by the realization that he can speak to animals, or at least, understand their language. Psaltis presents the animal language in a series of abstracted symbols, a solid choice that keeps the animal world alien but creates a longing in the reader to understand it better.

As the man explores his sudden understanding further he is taking on an increasingly unreal journey that evolves into an invitation to join the world he has come to understand better. But this is done through a lens of fear, of confronting that predatory emotion, of embracing it, of recognizing your own role in it, of becoming it.

In the end, the man opts for the human world by exhibiting one of the main differences between human and animal, at least, apparently — abstract thought. It’s this ability of humans to conceive of a world and then make it possible, to conjure the intangible as a real world presence on a grand scale, that separates us. And this reality separates us not only neurologically and culturally, but physically, and it creates myths about the animal world that work to separate us further from it.

But it’s hard to say that in opting for the human world, the man is rejecting the animal, or even making an informed decision at all. Is he just building his own prison? Or is he already in a prison and just acknowledging that fact? Are humans prisoners of their own abilities?

These are the kings of questions Kingdom/Order asks. It suggests that barriers between humans and the natural world are real because we have made them so, but that doesn’t mean the experiences in either are necessarily doomed to be exclusive.