Is nature our friend or our enemy, or maybe a little of both? Perhaps it’s not even measurable against the human experience, since we are the only creature that has willfully left it behind to craft our own world, and are certainly the only creature that could be characterized as its potential destroyer. I’ve read two books recently that covered different aspects of nature in different ways, and I found their presentations to be compelling enough that I wanted to talk about them together.

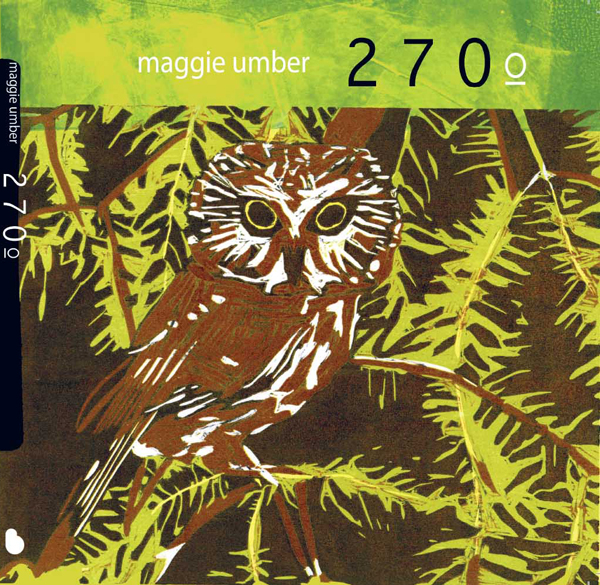

The title of Maggie Umber’s 270°, from 2d Cloud, refers to just how far an owl’s head can turn from the forward position, which is an apt symbol for how much territory Umber is covering in the book. Not so much a comic as an art book combined with a field guide, Umber takes the reader on an expansive examination of the existence of owls.

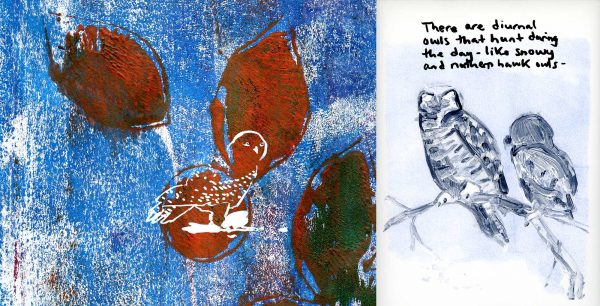

The text is sober and informative, providing basic facts about owls that eventually expand into specifics that take the reader deeper than you’d expect — in this way, I think this is a great book for kids.

The art, however, starts out as offering more than a clinical view of the creatures it captures and continues throughout the book as a method of getting to the mood of the life of owls and an attempt to pierce their very souls. Parts of Umber’s realizations are pure sketchbook and that adds some immediacy to the presentation, but there is no limit to the other vantage points Umber offers. Some images are illustrative and fanciful, some look like excerpts from unpublished and fully-realized narratives, some take the image of the owl into more experimental areas, and some are entirely abstract, offering textures that elicit emotion about owls and their lives and habitats more than facts, all utilizing various drawing, painting, and printmaking techniques.

Umber wraps these styles around plain language, and while it might be tempting to err on the side of poetry with these kinds of works, I think Umber’s choice is best, rendering a full experience that captures the multiple aspects of owls, both scientific and mythological.

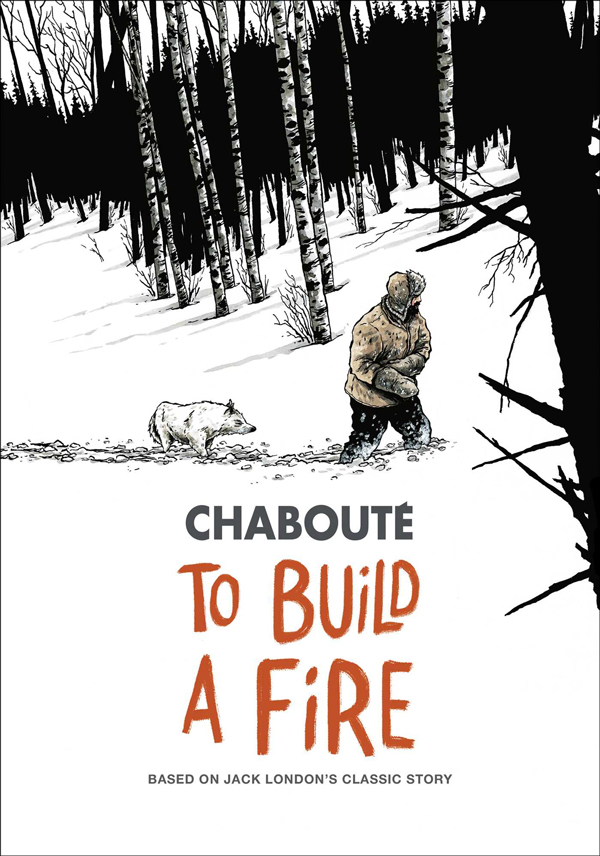

In the hands of French storyteller Chaboute, nature becomes the stage less for measured-though-passionate study and more for the strict terms of survival. Adapted from the Jack London story of the same name, To Build A Fire, published by Gallery 13, presents a poetic and sometimes surreal meeting between man and wolf the wild.

Much like Umber’s work, this too is a meditation on nature, but in the context of human brashness. Largely a troubled trek by a man in Yukon, Chaboute renders not the human penchant for the conquest of nature, but its proclivity at being defeated by it. Told in the form of rambling thoughts as the man struggles through the sub-zero temperatures accompanied by a white wolf like a ghost escorting him to his final resting place, Chaboute faithfully transcribes the last defiant thoughts of a man in the process of dying. Nature is getting the best of him and the wolf is the consciousness that witnesses it, makes it real in the universe.

Whereas in Umber’s presentation nature is elegant and mysterious and invites observation if not participation, Chaboute’s shows nature as cold not only in its climate, but in its emotions, especially when it comes to human participation within it. And as nature is irreversible from the universe itself, in watching the man’s fate, irreversible and resulting from his own presumptions, Chaboute’s book reads like a judgment of humankind, taking a step too far into the abyss without understanding warning signs or boundaries.

In presenting this mood piece, Chaboute outdoes himself with the art. Stark, grim, his work will freeze your soul just by looking at it as much as the man is frozen within it, sharing the space with the soulful wolf and intricate, delicate drawings of tree, with sparse color, Chaboute allows the emotional impact to walk side-by-side with a realistic representation of the situation, just like the man and wolf in the story.