Welcome to Queerness in Comics, a bi-weekly column by Avery Kaplan, which will explore queer representation and themes in comics. This week, Avery is exploring Queer: A Graphic History, originally published in 2016.

Publisher: Icon Books

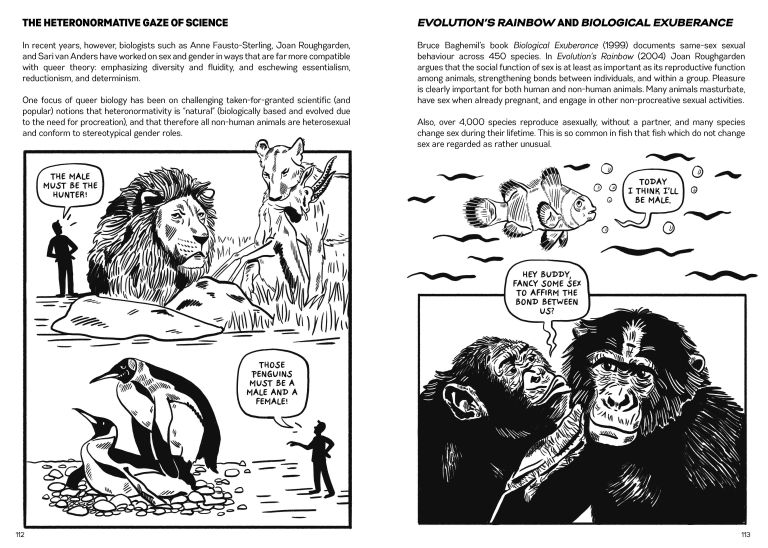

While many of the books covered by this column have been fictional narratives, comics can be an invaluable method of sharing factual information, as well. In part, this is thanks to the fact that information represented by an image can be so quickly communicated to the reader: for example, while a person may be able to glance at a page filled with words and refuse to read them, glancing at an image tends to instantly communicate the message.

On top of providing a method of effectively communicating information, however, including cartoons along with the history lesson can also make learning less intimidating. Words like “theory” and even “history” can make a text seem daunting, even when the ideas contained within are interesting and engaging. By including friendly graphic elements, and (dare I say it) a joke or two, it can help assuage fears that a book will be difficult to read because it concerns a more abstract concept.

So it is with the exceptionally informative Queer: A Graphic History by Meg-John Barker and Julia Scheele, a book that surveys some serious and complicated topics while engaging the reader with inviting black-and-white illustrations and cartoons.

Queer: A Graphic History

One of the very first topics covered by the book is the word “queer” itself. Queer: A Graphic History begins by tracing the origin of the word, noting that it originally was synonymous with “strange,” and divorced from any comment on sexuality or gender. To illustrate this point, the book includes a cartoon that illustrates a line from the short story “The Adventure of the Greek Interpreter” by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, in which Sherlock Holmes tells Watson, “The Diogenes Club is the queerest club in London, and my brother Mycroft, the queerest man.”

On the opposite page, the book dives into the origins of the word as a slur, noting that the first recorded use of the word as hate speech was by John Sholto Douglas, who used the word in a derogatory sense when accusing Oscar Wilde of having an affair with Alfred Douglas, John’s son.

From there, the book discusses the reclamation of the term, citing other instances of hate speech being reclaimed to illuminate the process (in the image on this page, a collection of Dykes to Watch Out For by Alison Bechdel is used to literally illustrate the reclamation of hate speech).

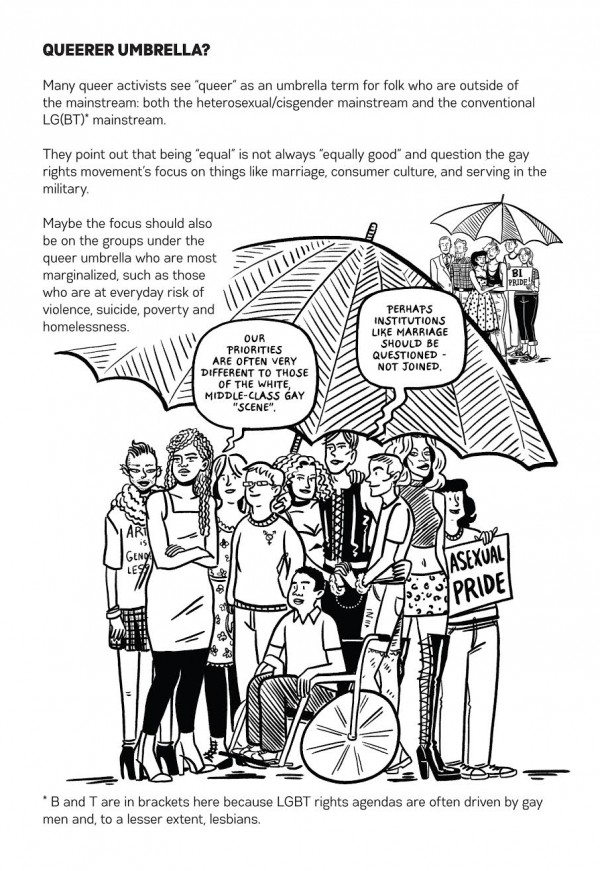

The three pages that follow are where the use of images become exceptionally interesting. As the book considers the idea that “queer” can be used as an umbrella term to unite anyone who is not heterosexual and/or cisgender. This idea is illustrated by a group of people standing beneath an umbrella.

However, on the next page, the idea that “queer” is a word that denotes a philosophy that does not involve attempting to be subsumed within a culture that has traditionally been hostile to those of us who fall outside of the “normative expectation,” but rather, questioning the tenants and institutions of that culture instead. To illustrate this point, a second group of people under and umbrella is shown standing in front of the first.

Then, on the third page, the text questions both of these philosophies, critically examining the ways they each may fall short. This concept is illustrated by both groups of people having their umbrellas threatened by a strong wind.

The three images on these pages tell a rudimentary sequential story even if the audience hasn’t read the text on the pages. This not only allows the book to impart two parallel lines of meaning – both through the images and the text – but also instantly informs the reader that the concepts explored on these three pages are casually connected. By providing the three related images, the book signals to the reader that the concepts explored therein are connected, even when the reader has yet to read a single word.

Nonfiction comics are invaluable resources

Queer: A Graphic History is an excellent example of how effective comics can be at imparting factual information. Just as Seeing Gender uses illustrations to help display the wide variety of non-binary identities, Queer: A Graphic History uses images in innovative ways to help ideas about queer theory and history be better illuminated that they may have been through a book that only included plain text.

Whether a reader is a member of the queer community or simply a reader who is interested in learning more about the ideas and language behind the concept of queer, this book is an invaluable and illuminating resource on the topic.