[Previous chapters: 1 to 8 – 1953 – 1985 Roundup]

From the beginning Dez Skinn had wanted to sell the Warrior strips further afield, with his most likely targets being the European album/bande-dessinée markets, and the enormous potential audience of the North American comic book companies. Skinn made a number of trips to the USA, which he often reported on in the pages of Warrior, right up to the end. He was hoping to sell all of the strips in Warrior together, with both individual character titles and a number of anthology titles. These were to have names like Pressbutton, Challenger, Halls of Horror, Weird Heroes, and of course Marvelman, all of which he made up dummy copies of, with the assistance of Garry Leach.

Skinn felt it would be easier to place all the titles if he offered them as a package, and that if all the creators presented a united front through him, it would be to everyone’s benefit. As he said to George Khoury in Kimota! The Miracleman Companion,

The deal that I was putting together was like the newspaper syndicate deal or films being sold to TV. If you want this one you gotta take the rest. It’s a package. It’s not a pick and choose. It’s not an a la carte menu, it’s a set meal. You take the lot or you get nothing. I knew strips like Spiral Path – which I put into an anthology alongside Shandor and Bojeffries Saga – were not the stars of the show, but they deserved to get US syndication. Everybody can’t be the star, somebody has to be the warm-up, the back-up. Somebody has to have their name below the titles. So I figured it wouldn’t be fair because without those guys we wouldn’t have had an anthology, we would have had a skinny little pamphlet. These guys deserved syndication as well. So, the deal was all of them or none.

The most obvious prospective American purchasers for the titles were DC Comics and Marvel Comics, both based in New York. Skinn already knew both Dick Giordano, who was Editorial Director at DC at the time, and Jim Shooter, Marvel’s Editor-in-Chief, so he flew over to New York and met with both companies, where he hoped his connections might help him to persuade one or the other to take the titles. First of all he talked to DC, where Alan Moore was by now working on Saga of the Swamp Thing, to enormous popular and critical acclaim. Jenette Kahn, who was at the time President and Editor-in-Chief at DC Comics, liked the Pressbutton title, but wasn’t necessarily crazy about the others. According to Skinn, again in Kimota!, Dick Giordano said,

We’d love to do Pressbutton, Bruce Bristow thinks Zirk is phenomenal, but DC Comics publishing something called Marvelman; are you crazy? Do you know the problems we have with Captain Marvel, and you think we’re going to do Marvelman?! I couldn’t touch it. I love it but we couldn’t possibly do it.

Of course, if Skinn had succeeded in selling Marvelman to DC Comics they would have been in the bizarre and unique position of publishing comics featuring Superman, his copy Captain Marvel, and his copy Marvelman, the three of them having originated at three different publishers: Detective Comics and Fawcett Comics in America, and L Miller and Son in Britain.

Having failed to sell his package of titles to DC, Skinn went to talk to Jim Shooter at Marvel Comics. Again, Marvelman proved to be a sticking point, both for its title and its contents. Skinn said,

Shooter said, ‘We can’t do Marvelman,’ and I said, ‘But you ARE Marvel!’ He said, ‘Yeah, but the trouble is if his name is Marvelman, he represents the entire company. It would be like if this character was called DC Man, he’d represent DC. We couldn’t have a figurehead character who’s involved in a bizarre sexual triangle with the wife who’d rather sleep with the Greek God superhero than the forty-year-old pudgy secret identity and all this other stuff. Besides, he’s British, so how could he represent us?’ So he didn’t want it either.

Although at one stage their distribution business had upwards of 800 wholesale accounts with comic shops, nearly 200 of these transferred their business to other distributors without paying for three months and more worth of stock received from Pacific. At the same time, there were lawsuits involving royalties owed for creator-owned properties they had published. All of this caused the company to find itself with an accumulated debt of around three quarters of a million dollars, and in August 1984, only three years after they began publishing comics, the Schanes brothers gave notice to their staff that Pacific Comics would cease to employ them from the following month. Marvelman was once more without a home, this time without a single page being printed.

It was at about this time that the legal letters from Marvel UK began to arrive, meaning that not only would Skinn need to find a new home for Marvelman, but would also have to find a new name for the character. Alan Moore in particular was not happy about this. He had already approached the powers that be at Marvel at the time, suggesting that they could change the title of the strip to Kimota!, in much the same way that DC had named their Captain Marvel title Shazam!, but they weren’t interested. As long as the character was to continue being called Marvelman, they were going to do everything they could to prevent it being published. He told me,

I was told that, when the new editor at Marvel took over, and he actually took over Jim Shooter’s desk, they apparently found a crumpled letter from Archie Goodwin to Jim Shooter saying, ‘Look, Alan Moore says that he’s not going to allow us to reproduce Captain Britain unless we allow him to call…’ – I’d suggested that we call the book Kimota! as a solution similar to the Shazam! solution – but no, I got some very stroppy letters back from people who once meant something at Marvel Comics, and were all-powerful and supreme, and are now probably working in Blockbusters. Archie Goodwin had said, ‘Alan Moore’s not going to be working for Marvel in any way, or letting us reprint Captain Britain, unless we ease up on the Marvelman deal,’ and he’d said, ‘I suggest that you go along with him.’ But Jim Shooter, who was another one of these comic book industry führers, whose will is not to be meddled with, he’d petulantly screwed this letter from Archie Goodwin up and thrown it in the bottom of a drawer somewhere.

Moore wasn’t happy about what he saw as very highhanded and bullying behaviour by Marvel Comics, and wanted to resist any efforts to change the name, but realised that it was inevitable that it was going to happen. He told me,

I didn’t like it, because it was actually accepting Marvel Comics’ bullying, so of course I objected to changing it.

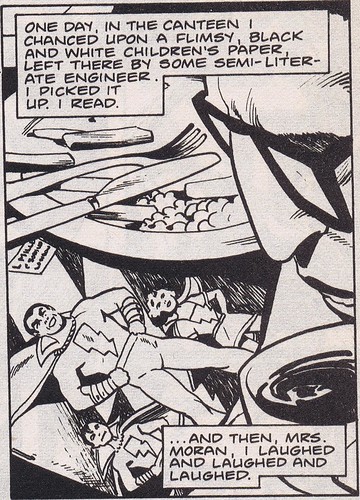

There were good reasons to object to the character being called something other than Marvelman. Part of the premise for Moore’s original Marvelman story was that the Miller-era Marvelman stories were a relevant part of the story, and were actually the plotlines for the fantasy scenarios that Dr Emil Gargunza fed into the minds of the sleeping superhumans. The fact that Marvelman was a direct descendant of the Miller-published Captain Marvel comics is acknowledged when Gargunza is telling the story of how he created Marvelman and his companions to Liz Moran in Warrior #20. He says,

The idea grew from my need to find a means of controlling these beings. I had decided to enslave their minds with dreams. With stolen alien science, I constructed a device that would shape their dreams and nightmares.

All that I needed was the appropriate fantasy… A pseudo-logical system that would explain their abilities to my over-men in a credible fashion. For six months I wrestled with the problem, to no avail.

One day, in the canteen I chanced upon a flimsy, black and white children’s paper, left there by some semi-literate engineer. …And then, Mrs. Moran, I laughed and laughed and laughed. …And went away and built my ‘Marvel Family’: your husband first, then Dauntless, then Bates. Rebbeck and Lear came later, but they need not concern you.

Almost inevitably, though, the new name suggested for Marvelman was Miracleman. After all, Moore had used the name before, both at the end of his initial pitch to Dez Skinn, where he said,

In the event of us not getting the rights to Marvelman then obviously I’ll have to rework all these notes. But possibly we could still do something featuring a pastiche character called Miracle Man who transformed himself with a cry of ‘Raelcun!’ or summat.

He had also used the name in the pages of the Captain Britain strip for Marvel UK, where he had a character called Miracleman make a brief appearance, as an obvious analogue of Marvelman.

Although the name Miracleman was put forward by Moore himself, he wasn’t necessarily happy about it. He told me:

I didn’t like it, I didn’t like submitting to bullying. When it became clear that that was the only way it was going to be – I think I’d suggested it as a fairly acceptable compromise, that if we were going to have to make one, then I suggested that that should be it.

None the less, the very fact that Moore had mused on the possibility of having to find an alternative name means that at some stage he must have contemplated the prospect of having to do so, and both Skinn and himself must have known there was always a strong possibility that Marvel Comics would not be happy with a character whose name was so similar to their own, regardless of who preceded who.

After a break of a year since Marvelman’s last appearance in Warrior #21 in August 1984, the first issue of Miracleman was published by Eclipse Comics with a cover date of August 1985, with the logos for both Eclipse Comics and Quality Communications featured prominently on the cover, and with Dez Skinn and catherine yronwode named as editors in the indicia. This was, as Skinn describes it on his website, ‘Conceived in Britain, coloured in Spain, printed in Finland and sold in America’.

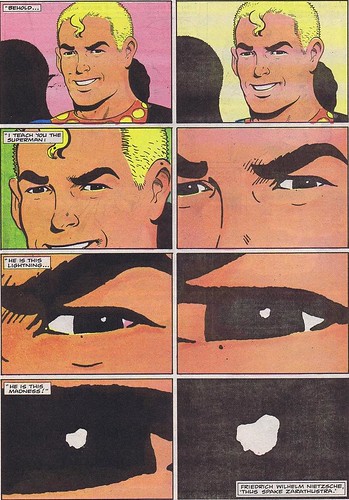

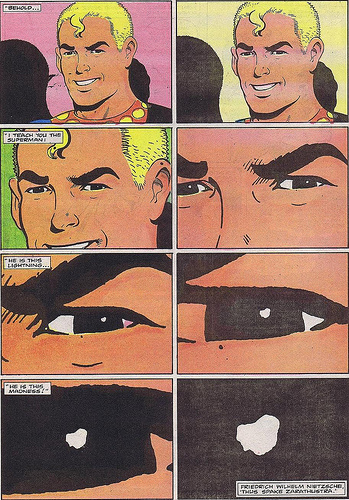

That first issue reprinted the Alan Moore and Garry Leach strips from Warrior #1 to #3, and actually opens with the Marvelman Family and the Invaders from the Future story from Marvelman Special #1 in May 1984, which had originally been published by L Miller in Marvelman Family#1 in October 1956, although this had not appeared when the first stories were originally published in Warrior. (And, if Marvel Comics ever get around to reprinting this, it will be it the presumably unique position of having been published by four different comics companies, on two sides of the Atlantic.)This strip was drawn by Don Lawrence, and probably written by him as well, although it is stated as being copyright to Mick Anglo in the indicia in Miracleman #1. This issue also contained a page of eight panels, consecutively tighter close-ups on the head of Marvelman from the last page of the Invaders story, finally ending up with a completely black frame. This is accompanied by this text:

Behold, I teach you the Superman: he is this lightning, he is this madness!

-Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra

Subsequent issues of Miracleman continued to reprint the mostly eight-page chapters of the story as they had originally appeared in Warrior, with the exception of very obvious lettering corrections where the word Marvelman had been replaced by Miracleman, and the addition of truly crude and awful colouring, credited from issue #2 to Ron Courtney. Issue #1 also reprinted Dez Skinn’s article on the history of Marvelman, which had originally appeared in Warrior #1, now slightly renamed to Miracleman alias Marvelman: Mightiest Man in the Universe.

Issue #2 contained a new two-page article by Alan Moore called M*****man: Full Story and Pics, where he gave a potted history of the character, and of his involvement with it. This is probably the first time he recounts the story of how he ‘came across an old and outdated Marvelman hard-cover annual in the racks of a bookstall on the windswept sea-front at Great Yarmouth’ and how this led to him imagining ‘the eternally youthful and exuberant hero as a middle-aged man, trudging the streets and trying fruitlessly to remember his magic word’. He also explains why the character had to have his name changed,

The strip seemed to be fairly well received, at least critically speaking, and managed to harvest a reasonable number of Eagle Awards during its stint in Warrior. The only real problems that have arisen have been those connected with exporting the title to America under the Eclipse banner. Despite the fact that ‘Marvelman’ has been a copyrighted character in England since 1954, it was feared that a certain major American comic company (not DC) might take exception to a comic entitled Marvelman being published upon its own turf.

Despite the fact that the company concerned hadn’t adopted their name until the very late sixties, it was decided that corporate clout and legal muscle would be more likely to decide the issue than such comparative trivialities as the concepts of right and wrong. Thus, the comic that you hold in your hand is entitled Miracleman. For all practical intents and purposes, the character that you read about in these pages is called Miracleman, has always been called Miracleman and always will be called Miracleman unless some jumped-up Johnny-come-lately outfit called Miracle Comics emerges in the early 1990s and forces us to change it to Mackerelman.

Hopefully, however, this little explanatory ramble might help you newer readers to bear the character’s previous history in mind as you read about his latest incarnation in the months to come. Try to remember two things: Firstly, he may be the bastard offspring of The Big Red Cheese, but he has Royal blue blood coursing through his veins.

Secondly, he isn’t really called Miracleman at all.

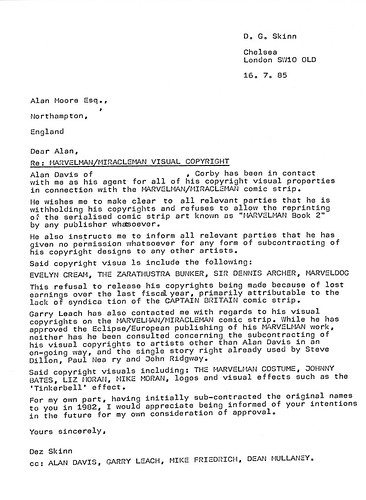

Issue #2 was comprised of strips that had been published in Warrior from #5 to #8, starting with Garry Leach’s last solo strip, then moving on to the two episodes that Alan Davis pencilled and Leach inked, and ending up with Davis’s first solo strip. However, despite Eclipse’s and catherine yronwode’s avowed espousal of creators’ rights, they did not have Alan Davis’s permission to reproduce his work, as is made clear in this letter from Dez Skinn to Moore and others:

Re: MARVELMAN/MIRACLEMAN VISUAL COPYRIGHT

Alan Davis of [address removed], Corby has been in contact with me as his agent for all of his copyright visual properties in connection with the MARVELMAN/MIRACLEMAN comic strip.

He wishes me to make clear to all relevant parties that he is withholding his copyrights and refuses to allow the reprinting of the serialised comic strip art known as “MARVELMAN Book 2” by any publisher whatsoever.

He also instructs me to inform all relevant parties that he has given no permission whatsoever for any form of subcontracting of his copyright designs to any other artists.

Said copyright visuals include the following:

EVELYN CREAM, THE ZARATHUSTRA BUNKER, SIR DENNIS ARCHER, MARVELDOG

this refusal to release his copyrights being made because of lost earnings over the last fiscal year, primarily attributable to the lack of syndication of the CAPTAIN BRITAIN comic strip.

Garry Leach has also contacted me with regard to his visual copyrights on the MARVELMAN /MIRACLEMAN comic strip. While he has approved the Eclipse/European publishing of his MARVELMAN work, neither has he been consulted concerning the subcontracting of his visual copyrights to artists other than Alan Davis in an on-going way, and the single story right already used by Steve Dillon, Paul Neary and John Ridgeway.

Said copyright visuals including: THE MARVELMAN COSTUME, JOHNNY BATES, LIZ MORAN, MIKE MORAN, logos and visual effects such as the ‘Tinkerbell’ effect.

For my own part, having initially sub-contracted the original names to you in 1982, I would appreciate being informed of your intentions in the future for my own consideration of approval.

Yours sincerely,

Dez Skinncc: ALAN DAVIS, GARRY LEACH, MIKE FRIEDRICH, DEAN MULLANEY.

It was while I was working with Jamie [Delano] that he told me about Alan being snubbed by Jim Shooter and, in retaliation, denying Marvel permission to reprint Captain Britain – nothing to do with the Marvelman name. I confronted Alan, told him to withdraw his objection to the Captain Britain reprints or I would deny Eclipse my Marvelman rights. Which I eventually did! Eclipse, Dez and Alan all ignored my protests/refusals and my work was stolen.

I asked him about this when I interviewed him recently. Here is a portion of that interview:

PÓM: When Eclipse reprinted your work on Marvelman, they did so without your permission, I believe?

AD: Correct. As explained above.

PÓM: Did you ever have any sort of contract or arrangement with Eclipse, and did you ever receive any payment from them for that work?

AD: No! and No!

PÓM: The same question goes for the collected editions of Miracleman that Eclipse did. Did you give your permission for those, and did you receive any payment for them?

AD: No! The only payment offered by Eclipse was as an attempt to get my agreement to allow Titan to publish a Miracleman collection in the UK. Which I blocked!

None the less Eclipse, despite their apparent commitment to creators’ rights, continued to publish issues of Miracleman containing Alan Davis’s artwork in spite of his objections, and even featured his name, along with Moore’s, on the front covers. In an article in Speakeasy #57 (Acme Press, 1985), catherine yronwode is quoted as saying,

Dez Skinn signed a contract with Eclipse allowing us to reprint material from Warrior, and we intend to reprint that material. If Alan Davis granted Dez Skinn the power to make that contract, and has since changed his mind, that is unfortunate for Alan but he is legally bound to that contract. If Dez Skinn represented himself to Eclipse as having the power to represent Alan Davis when in fact he did not, that is a matter for Alan Davis to settle with Dez Skinn. In any event Eclipse will be reprinting the material.

By Miracleman #3 Eclipse had added the line America’s #1 Superhero! to the masthead. They had also started getting big-name comics artists of the time to produce cover illustrations for them after the first two covers by Garry Leach, with people like Howard Chaykin on #3, Jim Starlin on #4, Timothy Truman on #6, and Paul Gulacy on #7, amongst a few others. There was also a rumour that Frank Miller was to draw a cover, but in the end this came to nothing.

Issue #6, cover-dated February 1986, marked the last of the reprint material from Warrior, but this wasn’t the end of Eclipse’s run on the title. Whereas Pacific Comics had only intended to reprint the stories that had appeared in Warrior, Eclipse had more ambitious plans.

To be continued…

Pádraig Ó Méalóid continues to be a middle-aged Irishman. He has been fascinated with the story of Marvelman for a very long time, and has written a book about it, which is currently looking for a publisher.

Has Alan Moore ever spoken about Alan Davis’s objections to the publication of his MM material by Eclipse, especially in the light of his public stance on creator rights?

When I saw the cat yronwode quote “that is unfortunate for Alan but he is legally bound to that contract”, I forgot what I was reading for a moment and thought that it was Jim Lee or Dan Didio talking about ‘Before Watchmen’!

I may have more on this later on. I can’t even remember, at this stage! Probably in next week’s piece.

When the article says “Some of the creators and titles that had started at Pacific went to other comic companies, like Elric of Melniboné, based on work by Michael Moorcock, which First Comics acquired the rights to after Pacific had already done the groundwork to introduce the character to the marketplace. Mike Grell and his Starslayer titles followed Elric to First, and Sergio Aragonés and Mark Evanier’s brilliant Groo the Wanderer went over to Eclipse Comics (before later ending up at Marvel), all of which caused prospective creators to think twice about signing up with Pacific.”, it gets things all out of order. Groo wasn’t published by Eclipse (as a title; Groo had first appeared in Eclipse’s Destroyer Duck title) until October 1984, after Pacific went under. The Groo Special which was one of the examples of Eclipse picking up what was left over when Pacific closed. Elric didn’t show up from First until 1985, after Pacific had closed; Starslayer certainly didn’t follow it there, as Starslayer showed up at First in 1983, and Elric was published by Pacific into 1984 (in fact, the first issue of Pacific’s Elric is dated the same month as the last issue of Pacific’s Starslayer, April 1983.)

Dagnabbit! I will freely admit that I’m no expert on Pacific, so it is entirely possible that I got some of these wrong. I’m not even sure what my original source for all those facts was, so I can’t point you at anything in my defence. I shall amend it all accordingly for next time ’round.

So has Alan Moore ever actually said that he had nothing to do with the Nietzsche quote?

the yronwode quote is pretty bad. you cant republish someone’s material without their permission and just waive away the concerns by saying you were told by someone else that it was all cool. its like, i can sell you my neighbors house if you want to buy it, but good luck trying to move in without a cleared title.

i don’t suspect she had anything but good intentions, but her attitude comes across as a tad too dismissive, to me, in that quote anyway. just another example of the perils of publishing creator owned work i guess.

i also love the Alan Moore passage from the Eclipse ish #2. very funny. and makes me kind of wish some issues of MackeralMan were actually produced at some point in the 90’s.

great work as usual, mr O Mealoid! its always a treat seeing these posts every sunday!

http://www.comics.org/publisher/427/

Ah, Pacific Comics. So much promise, and such beautiful covers and paper. And all over in a little over two years.

Arthur Spitzer: So has Alan Moore ever actually said that he had nothing to do with the Nietzsche quote?

He has neither confirmed it not categorically denied it, to the best of my knowledge. However, I’ve said this before, in a fairly high profile piece, and nobody contradicted me, including, for instance, Dez Skinn, who I know read this, and was co-editor on Miracleman #1. And, frankly, it doesn’t seem like the sort of thing Moore would do, from my experience of his work, and his work practices. He doesn’t go back and rewrite his work, ever.

jaroslav hasek: the yronwode quote is pretty bad.

Yes. It is.

i don’t suspect she had anything but good intentions…

I’m afraid I don’t agree with you. we’re not done with cat yet, so you can decide for yourself in another week or two.

25% p.a. for a credit? Yikes!

At the time Pacific and First were exciting new publishers, I remember their first monthly books arriving on the continent and buying them. But Eclipse not so much at first. I don’t think I ever stumbled upon an issue of Miracleman.

The yronwode quote is bad. I wonder if they did the rest of their legal stuff with the same attitude.

There is worse to come about cat yronwode. When I started all this, I though I had a reasonably good idea who were the goodies, and who were the baddies. One of the people I’ve had to majorly reappraise is cat, which will become more evident as I go along.

I’m sorry this is the first thing that jumps out at me about that article, but man, the Pacific folks were not businesspeople. Who takes a loan at 25% that isn’t a three-months-overdue credit card?

Sam – Interest rates weren’t always as low as they are today. In 1979 prime rates ranged from 12-15.50% with bank mark-ups from there.

Yes, 25% is a really high rate, but it was a crappy time in the economy. I’d imagine that a bank would have given pause to a comic book distributor trying an unproven model of publishing orignial material direct to the consumer. From the bank’s standpoint, the comics would literally have been worth the paper they were printed on, and not collateral. From Pacific’s standpoint, seems like the only way they were going to make it was to recruit and pay for top-name talent and build out demand and a distribution system that would work and generate a hit for them. It didn’t. But they did serve as pioneers, and they delivered some great comics!

Jon

“But they did serve as pioneers, and they delivered some great comics!”

Yes, they’ll be remembered for The Rocketeer, which helped to spark the Bettie Page revival. And for getting Kirby back into comics. The recession of the early ’80s probably didn’t help their finances.

There’s a comprehensive history of Pacific Comics here, for those interested. Perhaps I should have read it more closely!

Yes, if only for The Rocketeer, we should be glad they existed. A wonderful comic.

I miss those “ground-level” publishers of the ’80s — Pacific, First, Eclipse, etc. They provided a nice alternative to the Big Two, without being as extreme as the undergrounds. And prices were still low enough that I could buy a lot of pamphlets. Those were the days!

I have a very vague notion of doing some sort of a history of all those 1980s independent publishers. I’d better finish this one first, though…

I’d be really happy if you did a history of 80s independent comic publishers! That would be so awesome! There’s so much history there….

As for cat yronwode, I always thought she was one of the good people in comics. Then again, I used to think Dez Skinn was the Devil before I started reading your various columns. I’m really, really curious to see what we’re going to learn about yronwode. Half the fun of this, for me, has been learning who did what to whom and when it happened.

I more or less started all this with a ‘cat is good, but Dez is evil’ stance, too, but have changed my mind, in both cases. Dez was doing his best, and I think honestly believed he was in the clear to publish what he did. and I believe that too. cat, on the other hand, seemed to get nastier and nastier as she went along, not to mention perhaps a little crazed. All shall become clear.

I shall continue to give further thought to the history of ’80s companies. I’ll see what Herself says, first!

Ah, dragged in again with an internet speculation.

You never asked direct, Padraig, but, as the quote of mine you ran from my website states, the entirety of MM #1 was editorially packaged/commissioned/paid for by Quality. Everything from the cover art onwards – except the ads and that annoying roundup inside front cover Eclipse always used instead of specific editorials. Guess it was those which blessed me with a “co-editor”!

…So it wasn’t Eclipse at all on either the Lawrence strip or the Nietzsche page. Our by-then in-house art editor Garry Leach redrew/copied out the Don’s strip (the original newsprint version was way too blurry to use) as well as putting together AM’s Nietzsche photocopy enlargement page, which we all thought was a dead clever link to the new stuff. Eclipse weren’t editorially involved, thankyouverymuch.

I remember so well simply because despite me paying Annie Parkhouse the standard rate for lettering it all (I don’t think AM charged us for the Nietzsche quote!), Eclipse never paid me/Quality back for that either!

And don’t get me started on receiving royalties for collections or foreign editions. What are those? Obviously contracts were considered a one way street by some.

A final note: Alan Davis personally sent me that actual letter you ran, asking me to stick my name to it and send it out to everybody else involved, to make his clearly defined and understandably miffed stance clear. Unless you’d become DC’s darling these were seriously tough times financially. Most of us could really have used the anticipated income from reprints I’d always promised would happen if we did a good job and were literally banking on getting it.

Losing V for Vendetta from our pool, the MM reprints being held up over a surely trivial and unimportant name change, plus the spotty payments which followed when the US reprint actually did get underway meant some seriously poor cashflows! From such a promising start, most of the Warrior team was not terribly happy with the way things turned out.

If I’d only known then what I know now…

So whose idea was it to put the old Marvelman strip and the Nietzsche quote in, then? It sounds like you saying it was an editorial one, at you end. I presume at this point that Alan and yourself were no longer talking, so it seems unlikely to me that he had any input on all this, but you were there, and may be able to give a definitive answer to this.

The Don Lawrence MM strip was definitely my idea, to ground the character for a new audience before launching into the then-new version.

Good point that Alan had gone incommunicado by that stage though, except for the odd pithy letter, While he used to claim having a photographic memory, I’d say mine’s a more a selective one. Its very good but seems to choose what events to remember. But now you throw that point in, it must have been Garry who came up with using the Nietzche quote. Certainly not me, I was never that well read!

OK, thanks for that, Dez. Always a pleasure!

(And, if Marvel Comics ever get around to reprinting this, it will be it the presumably unique position of having been published by four different comics companies, on two sides of the Atlantic.)

Far from unique, unless I’m missing something, given decades of reprints and licensing of material from the US, France, Belgium, Italy, the UK and so forth in various directions. The first appearances of many Marvel and DC superheroes would have been reprinted dozens of times by various publishers. From this very post, The Rocketeer’s first chapters got to leap the Atlantic with the movie tie-in reprint of Eclipse’s album.

And to take another Alan Moore example, the first chapter of From Hell has been published by Spider-Baby in the US in association with Aardvark One International from Canada; by Tundra in the US; by Kitchen Sink in the US; by Eddie Campbell Comics in Australia but printing in Canada and distributed from the US; by Graphitti in the US; by Knockabout in the UK; and finally (if I’m recalling my chronology correctly!) by Top Shelf in the US.

That’s not counting the Australian edition by Bantam/Random House when the other Australian edition was barred from import (even further on the other side of the Atlantic. If you keep going.), or any of the translations into French, Italian, Spanish etc (obviously, different lettering in the balloons, but you’re allowing that for Mackerelman too…)

>> Far from unique, unless I’m missing something, given decades of reprints and licensing of material from the US, France, Belgium, Italy, the UK and so forth in various directions.>>

Yeah. Just picking handy-to-me examples, ASTRO CITY #1 has been published by Image, Homage and DC on this side of the Atlantic and numerous others around the world. THE WIZARD’S TALE has been published by Wildstorm and IDW, and multiple publishers in Europe.

kdb

Oh, one more weirdness that should be corrected: Padraig O Mealoid, you have attributed to me the “very heavy-handed foreshadowing” of using a quote from Nietzsche over a series of increasingly tight close-ups of Miracleman’s eye in Miracleman #1.

Nope. That was not me.

I am around on the net, at Facebook, and in my shop (which still has the same phone number that Eclipse used to have), and you could have easily asked me if i wrote the page.

Instead, you have let us know that you didn’t like the page and you have let us know that you don’t like me, and you have let us know that you do like the writing of Alan Moore. Then, using some sort of convoluted lit-crit puzzle-logic, you have opined that i, whom you dislike, must have been the one who wrote the page that you dislike because Alan Moore, whom you like, would never have written a page you don’t like.

If you are intending to place this material with a publisher, as you say you are, I would suggest that you contact the parties involved and interview them. Get their memories down in text form. Don’t manufacture a past that never was.

Kate Halprin and jaroslav hasek: — Why does my statement that the two parties (Alan Davis and Dez Skinn) would be bound by their contracts *if they had any* seem so upsetting and “bad” to you?

Contract law is the basis of creator rights. Unless one signs a contract under duress or by guile — and i had no reason at the time to suspect either Alan Davis or Dez Skinn of duress or guile — signing a contract is the most powerful way of stating one’s own sincerity and one’s belief in the sincerity of another person.

Eclipse had a legal-seeming contract with Dez Skinn. Eclipse was legally bound to uphold that contract, just as Dez Skinn was. That’s why i wrote, “Dez Skinn signed a contract with Eclipse allowing us to reprint material from Warrior, and we intend to reprint that material.” Most publishing contracts contain some sort of timeliness clause, too — that is, holding the publisher to a publishing schedule of some sort, with a forfeit of the contract as a penalty for failure to publish after a set amount of time.

The only way to set a contract aside is through a legal challenge or suit, and that is what i stated, simply and clearly, when i wrote, ” If Alan Davis granted Dez Skinn the power to make that contract, and has since changed his mind, that is unfortunate for Alan but he is legally bound to that contract.” In other words, Alan having a change of mind would not be sufficient to void a contract *IF* a contract had been made.

I also had some questions as to whether Dez represented the material legally. This is what i was getting at when i wrote, “If Dez Skinn represented himself to Eclipse as having the power to represent Alan Davis when in fact he did not, that is a matter for Alan Davis to settle with Dez Skinn.” I was hoping to draw out the truth from Alan Davis rather than hearing through third parties that he was upset. He was a grown man — either Dez had made a contract with him or not — and he could speak for himself at any time.

In my opinion, contract law is among the simplest and most elegant of the legal arts. It is, as Will Eisner once told me, “trust made evident.” He also said, “Any deal worth a hand-shake agreement is worth your putting your signature on a piece of paper. Never do business with a man who tells you his word is good but who won’t sign a simple contract, and never be afraid to sign a contract yourself, if you think you can uphold your end of the bargain.”

catherine yronwode: “I also had some questions as to whether Dez represented the material legally.”

At the time?

Lance Parkin — Thanks for asking about the time-line. This is a lengthy reply, because it goes to my own personal history as well as to the history of the publishing of Miracleman.

My grandfather was a copyright and trademark lawyer, and i have worked in various positions in the publishing industry and book trades since i was a teen. I knew from a young age what a publishing contract looks like, what a reprint contract looks like, what public domain laws are, and how copyright duration (and hence public domain laws) differ from nation to nation and over time.

Prior to working for Eclipse i had edited books for other publishers who had reprint contracts with comic strip syndicates and comics publishers, so my knowledge was practical and up to date.

At the time that Dean and i met with Dez Skinn’s agent, Mike Friedrich, i believed (as i was told by Mike Friedrich) that Dez Skinn had legal and contractual agreements covering all of the reprint material — that is, the reprint rights to old L. Miller work and the reprint rights to the Warrior work — and that, through Mike Friedrich, Skinn was entering into a negotiated contract whereby some of the Warrior principals would be creating new material for Eclipse.

At this meeting i personally came to understand that Pacific Comics had previously signed a similar contract with Skinn (again, through Skinn’s agent, Friedrich), that the Pcific contracted had been voided as a result of Pacific’s bankruptcy, and that Eclipse was being asked to pay a higher per-page rate for Warrior reprints than Pacific had agreed to pay.

We did not meet with Dez Skinn at that time, only with Mike Friedrich, his agent, and Friedrich did not indicate in any way that he doubted Skinn’s authority to engage in business as a rights-holder in Warrior’s interests. So, at that time, i was told that Dez held certain rights and would transfer them to Eclipse, and i had no reason to doubt what i was told.

(By the way, you might wonder why i was at this meeting, since i did not enter into financial transaction negotiations for Eclipse. I was present as an editor, to ask questions about how this unprecedently complex shared-creator-rights deal would be structured in terms of Eclipse’s editorial oversight, should Skinn sell his rights to Eclipse. In other words, my role was to determine whether the amount of editorial oversight permitted by the contract would be sufficient to enable the production of a marketable series — not only in terms of artistic creativity, about which i had no doubt — but also in terms of production under American deadline conditions in the direct sales market, which included the prospect of distributor cancellations if publication deadlines were not met.)

Later, by the time i wrote the material quoted above, i had heard many accounts of financial complaints between and among the various former associates at Warrior, about and against one other. The nature of these complaints, and the fact that i never saw any paperwork myself and was hearing some of the complaints second or third hand, resulted in my being unsure who held the truth, and therefore i couched my statement as a pair of opposing and contradictory viewpoints, with the adjuration that the parties who were involved should seek redress against one another, if their complaints were valid.

In a sense, i was asking for them all — each and every one of them — to “put up or shut up,” because their financial claims and counter-claims were always couched in emotional terms, with no hint of what i had been taught from an early age were standard contractual business practices.

What i was suggesting was that if the various parties to the Warrior material had a dispute amongst themselves, their complaints could not invalidate Eclipse’s contract with Skinn unless they could get a court to enforce their breached contract with Skinn — and if they had not signed a contract with Skinn, then their best recourse would be to take Skinn to court on a charge of arrogation of rights which had not been assigned to him.

In either case (on charges of breached contract or on charges of false arrogation of rights) , a victory for them would invalidate Skinn’s claims and might also invalidate Skinn’s contract with Eclipse, the latter leaving them free to negotiate new contracts with any publisher of their choice, and forcing Eclipse to sue Skinn for false representation. To my way of thinking, their taking decisive action seemed to hold a better promise of resolution than had their previous rounds of complaints and complaints-by-proxy … some of which continue to this day.

Comments are closed.