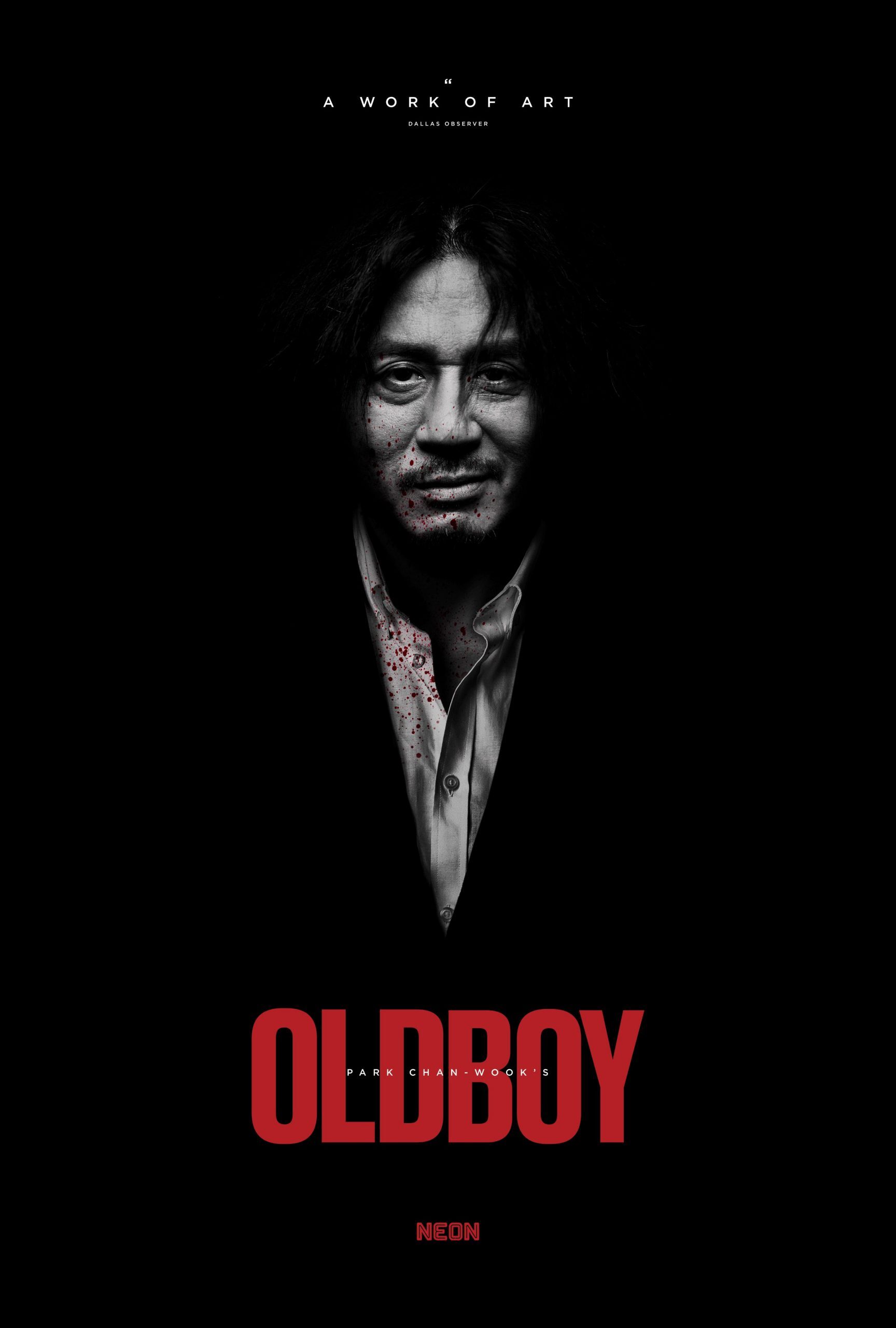

Review by Gabriel Serrano Denis

Back in 2005, one year after it won the Grand Prix award at the 2004 Cannes Film Festival, DVD copies of a strange Korean film titled Oldboy popped up in video stores in North America, notably bearing a critic’s blurb highlighting Quentin Tarantino’s love of the film. Tarantino’s seal of approval was a huge draw for moviegoers, ranging from the cinephile up to date on festival news to the more casual film browser. However, once people began to watch Oldboy, word of mouth quickly evolved from “Tarantino-approved film” to

“one-of-a-kind, must be seen to be believed violent spectacle.”

It was difficult to engage in a discussion of the year’s offerings without someone bringing up Oldboy and its shocking story and imagery (not to mention that jaw-dropping hallway fight!). Now, 20 years after its premiere, Oldboy is back in a 4k restoration from NEON,

looking as dirty as ever and still as original as only fearless cinema of its caliber can claim to be.

Based on the manga by Garon Tsuchiya and illustrated by Nobuaki Minegishi, Oldboy quickly lets its audience know that they’re not seeing the average revenge movie. We open on Oh Dae-su (Choi Min Sik) speaking to a man who’s about to fall off a building, grabbing onto him by his necktie and urging him to listen to his story. The story of Oh Dae-su is a tragic one: he was kidnapped on his young daughter’s birthday and imprisoned in an oddly well-furnished room for 15 years. Throughout his stay, he planned his revenge on whoever bestowed this wicked torture, training his body to fight and endure pain while he discovered on the room’s television that he had also been framed for the murder of his wife.

Suddenly, he is set free, and first encounters the suicidal man on the rooftop. After recounting his current predicament, he sets out to find whoever did this to him, meeting a chef he saw on his room’s TV along the way and letting her join his quest. Things turn violent, Oh Dae-su eats a live squid, and everything seems to point to the fact that Oh Dae-su was let out with a purpose, his torturer toying with him at every turn.

Approaching the story with the precise eye of early David Fincher and the gonzo editing of Seijun Suzuki, Park Chan-wook infuses Oldboy with style to the point of overflowing, yet it never overtakes the violent humanity at its core. Like Fincher, Park also heightens the absurdity of Oh Dae-su’s situation with bursts of surreal CGI imagery, throwing us deeper and deeper into the character’s mental state. In this sense, Park’s stylistic impulses are always in favor of the characters and their journey into darkness. Chung Chung-hoon’s

cinematography in turn has become emblematic of the representation of the darkest nooks and crannies of the Korean underworld, and along with Park’s eye for detail, the staging of action and violence is so impactful that it never calls attention to itself.

In a way, Park appears to want to surprise us every chance he gets. When Oh Dae-su exits a room where he just tortured a thug, little do we know that it will become a one-shot fight along a hallway packed with criminals wielding knives and pipes. Yet despite the hyper-stylization and expressionistic framing and lighting, the camerawork and Park’s blocking put the film’s most vital element front and center at all times: Choi Min-sik’s deranged and intense performance as Oh Dae-su.

No amount of blood or skull-cracking can prepare viewers for the raw display of emotion from Choi Min-sik. Most people will speak of the fact he eats a live octopus as it writhes and tangles around his mouth, or about the single-take hallway fight, and while these are undoubtedly iconic moments of contemporary cinema, Choi Min-sik’s embodiment of Oh Dae-su is equally iconic. His mess of hair and worn-out features, looking like he hasn’t slept in the 15 years he was imprisoned, make for a silhouette that is unmistakably Oh Dae-su. But it’s Choi Min-sik’s ability to go from deadpan mystery man to rage-filled animal that catches audiences off-guard. And even within those extremes, he also manages to let out bursts of humor as he relishes the suffering he dishes out. That smirk at the end of the infamous hallway fight, as piles of men fall over each other in the background after the beating they endured, is perhaps the shot that encapsulates Choi Min-sik’s commitment to Oh Dae-su. He allows us to root for him when beating down those deserving of his punishment but also to see the tortured soul within and the irreparable damage done to his humanity.

Every element in Oldboy is in constant conversation, the violence and dark humor informing the content and vice-versa. This is why the film never becomes pure shock value—Oh Dae-su’s violent revenge is nothing compared to the mystery of his capture and release. As we endure his painful imprisonment and eventual path to revenge, Park allows us to unravel the mystery with him, to the point of empathizing with him as he dispatches criminals and torturers. But this proves to be a trick by Park because we know nothing of Oh Dae-su’s past and he will make damn sure we’ll all share in his rude awakening.

It’s a strange film in the sense that it becomes more grounded as it unravels. Rather than going grander and more shocking, the film actually becomes more human, with a nuanced explanation for the pain Oh Dae-su has endured that hits all the harder precisely because our feet are on the ground by the time we’re hit with the sledgehammer revelation. As if the violence and dirty underground dealings weren’t enough, Park misleads the audience and flips the narrative so violently that the most shocking moment in the whole film is merely spoken rather than bludgeoned. This is Park’s greatest trick: letting us enjoy the carnage offered by genre filmmaking to reveal the disgusting side of human nature buried beneath the floorboards.

Oldboy is essential viewing in today’s cinematic landscape. In a time where films have gone more inward and “realistic”, Oldboy reminds us that the surreal and the shocking can co-exist with the personal. Similar to his Korean cohort, Bong Joon-ho, Park can give us thrills while attacking our preconceived ideas of morality in the turn of a scene.

Park continues to shock and innovate, from his follow-up films Lady Vengeance and Thirst to recent offerings The Handmaiden and Decision to Leave (again taking home a directing prize at the 2022 Cannes Film Festival), showing that his command of genre and human drama is truly one of a kind. Never the one to film or edit any scene conventionally, Park still displays the inventiveness of the filmmaker who made Oldboy.

Whether you saw it in 4k or on DVD in 2005, it is sure to leave a scar. And that ending still hits harder than any hammer to the forehead.

Oldboy is now available on 4k UHD from NEON.