By Kelly Kanayama

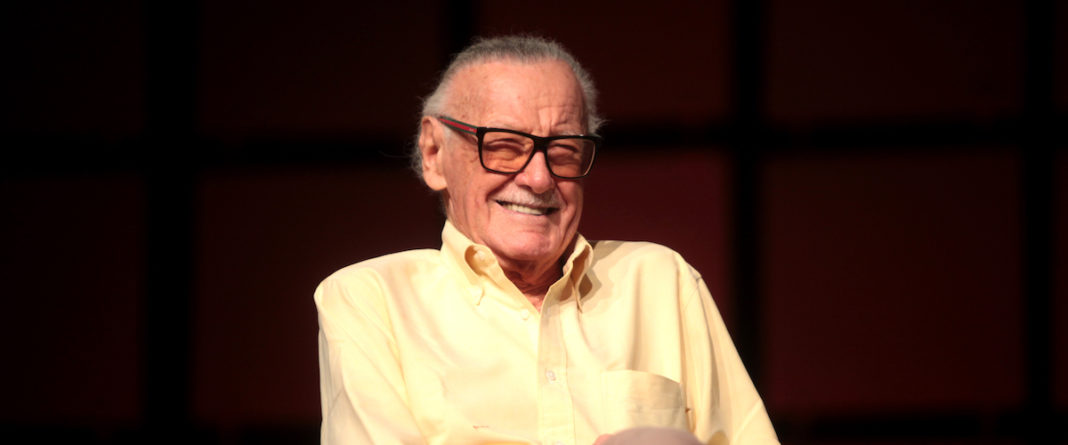

The Excelsior! Remembering Stan Lee panel felt like we’d all been invited to a wake held by the comics industry, in a good way. Moderator Danny Fingeroth led panelists Michael Uslan, Denis Kitchen, Paul Levitz, Jim Salicrup, and Todd McFarlane through an hour of reminiscence, where everyone shared their favorite Stan Lee story and reflected on what made him such a significant figure in comics and pop culture.

Fingeroth opened proceedings by giving a short background on each panelist’s professional background and connection to Lee, as well as his own. (He has written a biography of Lee which comes out next month, and has edited several Marvel comics.) The only exception was McFarlane, who arrived late; having to forgo his introduction was, Fingeroth said, “what he gets for being tardy.”

Fingeroth then outlined Lee’s early years in the comics industry with a selection of archive photos. He began by commenting on Lee’s image – “That was everybody’s impression of Stan for the first five years: Frank Sinatra with a comic book in his hand” – then talked about the 17-year-old Lee getting his start at Timely Comics and working on World War II propaganda, the most famous of which was an anti-VD campaign. Other photos showcased Lee in the 1960s sporting a “hipster” beard, side-hugging Jack Kirby in happier times for the duo, and holding an original page of Strange Tales. Fingeroth also touched on the first comics that Lee co-created: The Fantastic Four with Kirby, Spider-Man with Steve Ditko, and Ziggy Pig and Silly Seal with Al Jaffe.

At this point McFarlane arrived, and despite Fingeroth’s earlier pronouncement did get a bit of an introduction centering on his to-be-awarded Guinness World Record for the longest-running creator-owned comic. Initially Fingeroth stated the record was for the longest-running independent comic, but McFarlane quickly corrected him, adding that corporations can own independent publishers.

The panel resumed with an anecdote from Uslan, who recalled sitting next to Lee and Bob Kane at the premiere of the 1989 Batman movie, which he produced. He then talked about how the experience inspired him to bring Lee over to DC Comics to reimagine its central characters, such as Superman and Batman, for Stan Lee’s Just Imagine. During their work on Just Imagine, Uslan said, he had the experience of “being Jack Kirby” when Lee struck a pose and told him to draw it for a particular Superman panel. In that moment Uslan remembered the stories about Kirby drawing Lee that way, and felt like he was partaking in that legacy.

Kitchen’s contribution revolved around Comix Book, the quasi-underground comic he and Lee produced for Marvel. He praised Lee’s decision to let Comix Book’s creators retain their original art and the copyrights on their work, and to give them free editorial rein. He noted, too, that the decision was not popular with other Bullpen artists, who did not enjoy the same creative control or freedom and thus wondered, “why are you giving these hippies a better deal than you’re giving us?”

He also recalled the title that Lee chose for himself: “the Instigator.” According to Kitchen, Lee explained that being an instigator absolved him of blame if things went wrong – “I just instigated it!” – but made him look good if they went well.

Kitchen then shared a Lee story that actually focused more on one of his employees, specifically a secretary whose contest-rigging led to the birth of MAD Magazine. In the mid-1940s, Lee’s secretary Adele Hasan was a huge fan of Hey Look!, a humorous one-page filler strip published in various Timely Comics titles that was written and drawn by Harvey Kurtzman. Lee was considering phasing out Hey Look!, which Hasan was adamantly against but couldn’t weigh in on due to her subordinate role. To help him make the decision, Lee held a contest where Timely readers could send in ballots to vote for their favorite strips; if Hey Look! fared badly, it would get the axe. Hasan, who was responsible for collecting and counting the votes, noticed that hardly anyone had voted for Kurtzman’s strip, so she “stuffed the ballot box” with votes for Hey Look! – all from her. Lee was surprised by what he thought was an overwhelmingly positive response to Hey Look!, and began giving Kurtzman more and more work. Kurtzman’s success at Timely gave him the impetus to eventually start his own publication, MAD Magazine. As a side note, Kitchen said, Kurtzman’s increased workload from Timely meant that he came to the office more often, which gave him and Hasan time to fall in love and get married.

The next panelist to speak was Levitz, who looked back on the gradual development of his professional relationship with Lee, which in time became a friendship. He recalled going to Lee’s house for dinner one evening and bringing all of his Avengers collections for Lee to sign: “I’ll be a grown-up at dinner,” Levitz remembered saying, “but this is for 12-year-old Paul.”

Levitz then talked about the “two Stans,” his term for Lee’s public persona versus his private self: “I really describe Stan in terms of both the avatar, which was very natural to him…and the inner Stan, which didn’t show up very often.” He noted that Lee was “always on,” even at home with friends.

He followed this up with an anecdote from the 1990s about Marvel wanting Lee to do more editorial work and Lee asking him for advice on what to do. Levitz reminded him about all the industry greats he’d worked with, such as veteran artists Don Heck and Dick Giordano, to which Lee replied, “I was never much of an editor; I just wrote all the stuff!”

Levitz rebutted with, “The only one who ever got them to do anything beyond professional was you.” As an example, he cited his own interactions with Giordano, which he described as straightforward and all about getting the job done. But for Lee, he said, “when Dick was working for you, you got him excited.”

Salicrup had the floor after Levitz, and started off with a story about Lee getting invited to the premiere of Titanic. (The invitation came because James Cameron was in talks with Marvel to do a Spider-Man movie, which never came to fruition.) Paparazzi were taking lots of photos of everyone on the red carpet, including Lee. When Lee related this to Scott Lobdell – “I couldn’t believe the attention I was getting!” – Lobdell told him, “They all thought you were one of the last survivors of the Titanic.”

Salicrup also illustrated Lee’s editorial approach with a recollection from their time working together on Just Imagine. DC’s editors, Salicrup said, occasionally wanted to suggest small changes to Lee, which didn’t go over well. “once he did something he certainly didn’t want to change it for anybody.” Lee would listen to everyone’s input and then quash it with, “those are all great suggestions, but the name of it is Just Imagine If STAN LEE Did Superman!…So it has to be me!”

After this came a story from the early days of the internet, when Salicrup worked for Stan Lee Media, Lee’s short-lived online platform for attempting to launch new superhero properties. It was “really ahead of its time in both a good way and a bad way,” said Salicrup. On one hand, “it was like superhero YouTube,” with short animated videos about superheroes that people could consume online in bite-sized chunks. On the other, these were the years of dial-up and 56K modems. So for a three-minute cartoon, “it would take 3 hours to download the damn thing.”

Salicrup then recalled his time as the voice of “Stan 2.0,” a Stan Lee Media character who was essentially an evil Stan Lee clone, for one such cartoon. He would sometimes do impressions of Lee’s distinctive speaking style around the office – but never around the man himself, of course, until he was asked to voice Stan 2.0. Suddenly, Salicrup said, he was having to imitate Lee while Lee was watching him, which was a bizarre experience.

McFarlane was up next, choosing for some reason to deliver his recollections in a half-standing, half-bent over position. “I had three phases of my time with Stan,” he said, the first of which began at the age of 16 when he traveled to Florida to compete in a baseball tournament. There was a comic convention happening at the same time, and so the young McFarlane decided to visit. “At one of the tables was Stan Lee. This was royalty to me.”

Being a teenager with budding notions of getting into the comics business, “I asked if I could ask him a couple questions,” said McFarlane. “He pulled out a chair next to him and said, ‘Sit down, my son’.” Not only did Lee answer his questions, the two ended up chatting for several hours until the con closed.

Phase two began at the dawn of Image Comics in the early 1990s, when McFarlane and co-founder Rob Liefeld were breaking away from Marvel to start their own independent creator-owned company. McFarlane said that he was worried about how Lee would react to the schism, especially when the three of them met up on the set of The Comic Book Greats, a video series where Lee interviewed big-name comic artists about their craft. You can watch the full Lee/McFarlane/Liefeld episode here, which features quotable gems like “Kids love chains”. Just before the shoot, said McFarlane, Lee dispelled those fears, expressing enthusiasm and congratulations regarding his move away from Marvel toward Image.

The final phase revolved around McFarlane becoming Lee’s “professional introducer,” providing introductions for Lee at large public events. One such event, a screening of the first Iron Man movie in Las Vegas, left Lee “so enamored” of McFarlane’s skill that he asked McFarlane to continue introducing him, almost like half of a double act, at other events for the foreseeable future.

McFarlane recalled introducing Lee’s acceptance of a Walk of Fame star, which, he said, “legitimized comic books to the world.” To finally have someone from the comics world on the Walk of Fame, he explained, felt like a statement of purpose: “Here we come. The movies are coming, the TV is coming.”

He also provided a counterpoint to Levitz’s concept of the two Stans, stating that “The Stan Lee that you saw talking to you or on stage was the same Stan Lee off the stage. He almost didn’t turn it off,” and backing up his credentials by noting, “I’ve been on stage with Stan arguably more than any other human being.” This attitude was perhaps most apparent when Lee met the public, according to McFarlane: “he understood, more than any other celebrity I’ve ever been around, that those 30 seconds are the most important 30 seconds” to an adoring fan shaking hands with their hero. Dealing with so many fans was never a burden to Lee, who “got as much joy out of you as you did out of him.”

McFarlane then began talking about Lee’s failing physical health in the last years of his life, and the passing of Lee’s wife several months before his death, just short of their 70th anniversary. “If you did an autopsy on [Lee], I bet it would show he died of a broken heart.” At this point McFarlane teared up, inducing similar tears in many audience members.

“Who the hell goes out on top at 94?” asked McFarlane. Lee did, he said; that’s who.

The panel concluded by returning to Fingeroth, who reminisced about his time editing Lee’s writing on a Spider-Man annual and shared an example of Lee’s indomitability. Near the end of his life, Lee appeared at a con for what was supposed to be an hour-long panel moderated by Fingeroth. However, Lee was ill from a bad reaction to a flu shot, so the organizers said the panel would have to be cut to 20 minutes. When the 20-minute mark came up, Fingeroth started to wind things down as planned, but Lee stopped him. “Is God talking to you?” Lee asked. “Did he tell you we have to stop?” Despite his poor health, Fingeroth recalled, Lee powered through to fill the whole hour, revived by the energy of being on stage in front of his beloved public.

Fingeroth then threw in another quick plug for his biography of Lee, prefacing it with, “In tribute to Stan I’m going to sell something.” To close out, he played a video of Lee wishing Al Jaffe a happy 95th birthday, where Lee riffed on their co-creation Ziggy Pig and Silly Seal, looked back at their long friendship, and gave one last “Excelsior!” to Jaffe – and, at least in that moment, to an audience who would have been hard pressed to think of a more fitting sendoff.