By Ricardo Serrano Denis

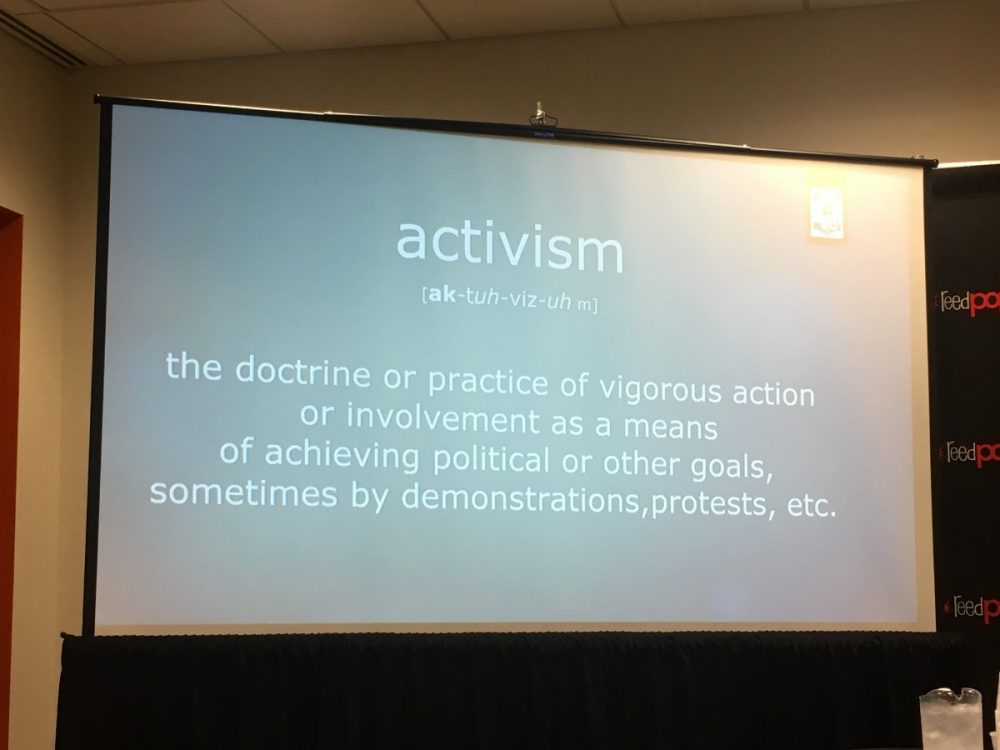

Comic books have a history of speaking out against tough topics in times were divisiveness, social strife, and even trauma are laid bare and haven’t even started to heal. One of the reasons why they do so, mostly, is because their weekly single-issue publication model keeps them current. They are intensely contemporary and they have an enviable time-sensitive window of opportunity that allows them to address subjects that are developing just as these comics are being published. Because of this, comics can also react to present problems. They become topical and timely. They become creative products of activism that can engage with the current political climate as it develops.

This is the idea that Comic Book Legal Defence Fund Deputy Director Charles Brownstein so eloquently argued in his panel “Comics Changed the World: CBLDF’s History of Activism Comics.” The time slot afforded to this panel was unfortunate. It took place in room 1B03 at 7:45pm. Having been present there and taking in what can easily be considered a masterclass in comic book history, I believe the topic was important enough, essential even, to justify an earlier time in the schedule. In the midst of national political distortion and social anger over those who hold certain positions of power, this panel was an excellent space for the kind of debate that needs to be happening everywhere.

The panel was set up as a history of activist comics and how certain iconic characters and underground comics creators took the call to argue for justice, policy changes, and unjust social treatment of underprivileged groups. It covered early 20th Century all they way to current times.

Brownstein made it a point to let the audience know that comics were talking about social justice when social justice itself was even a thing (much like we understand it today). In fact, due to their immediacy, in-your-face nature, social justice interests, and how they challenge the durability of outdated establishment structures, comics can be said to have activism deeply ingrained in their DNA. A lot of this rests on comics making full use of the 1st amendment, the right to free speech and expression. “We may not be brothers and sisters, but we are neighbors,” says Brownstein when discussing how comics tried to inform readers and how to treat their fellow citizens.

Early examples of Superman comics, for instance, show the man of tomorrow quashing domestic violence disputes, putting the male figure in a position of weakness that needs to be considered a larger social problem rather than a portrayer of an exception to the rule. “Superman is the original social justice warrior in comics,” argues Brownstein. He was the common man’s hero. This idea gets furthered cemented during the Depression, where Superman fought against corrupt bankers looking to foreclose the homes of poor families. Brownstein reminds us, “Superman was a radical character.”

Examples such as these were plentiful in Brownstein’s presentation. Stepping back to the First World War, we see Winsor McCay’s work as dissenting against war, violence, and how society should be governed. His strips sometimes took a kind of Little Nemo in Slumberland feel to drive the metaphors through. One political cartoon, for instance, shows the Grim Reaper shopping for meat in a butcher’s stall, the tagline “The Best Customer” accompanying the image.

Superman laid the groundwork for Captain America, one of the original pop culture Nazi punchers. Propaganda during WWII recognized the power of comics and enlisted it in the war effort to get readers to act according to the examples of patriotism and duty exuded by characters such as Captain America, Captain Marvel Jr., Wonder Woman, Nick Fury, Bucky Barnes, and so on.

Brownstein reminds us that during WWII, comic were read by people in the late teens to early 20s age group. These readers were soldiers, workers, boys, and girls that found inspiration and important information in comics.

Harold Gray’s Little Orphan Annie decided to practice another type of activism in speaking against government intervention on social problems, such as poverty and public housing and programs. It favored a “pull yourself up by the bootstraps” type of discourse while also allying itself with the pro-WWII cause. Annie wanted more people involved in politics, to shape policy. Comics about President Truman, Li’l Abner, Bald Iggle all spoke out on the era’s many challenges to having Americans show a unified but critical front against the social and cultural ills doled out by the world.

The American Spirit, according to Brownstein, was at play here. Comics embodied that spirit. The 50s, 60s, 70s, and 80s, contain more than enough examples that prove how comics have been at the forefront of public discourse and debate. Robert Crumb’s contribution to showing the ugly trends of social behavior in America contrasted well with the legacy of EC Comics’ confrontational brand of comics storytelling and activism—one that was so powerful that it sparked the Comics Code debate.

Female writers took the 1960s to counteract male sexism in comics with comics such as It Ain’t Me Babe, where creators such as Crumb were challenged for their depiction of women in a time where gender equality was being aggressively sought after at a policy level.

Brownstein mentioned National Lampoon and Steve Engelhardt’s Captain America: The Secret Empire storyline as example of activism against Vietnam, the My Lai Massacre, and the Nixon presidency. Neal Adams and Denny O’Neill’s Green Arrow/Green Lantern comics join the fight with stories centered on Native American treatment in 20th century America and racism. During the 70s, Howard the Duck ran against President Ford’s reelection campaign, something Brownstein and I think most of the audience wouldn’t mind seeing on the next election.

Watchmen, V for Vendetta, and Alison Bechdel’s Dykes to Watch Out For strip, come in a time where Reagan’s presidency is in full power but acting against American interests. Bechdel’s work was a beacon of light at a time where the President was afraid to say AIDS in public, thus leading to a general sense of ignorance and fear throughout the country, which also bread discriminatory resistance against the LGBTQ community.

The panel’s foray into the 90s and the present served as an examination of the current state of activist comics. The September 11th, 2001 terrorist attacks sparked an immediate response from the industry that called for unity in the face of catastrophe. Comics were one of the first mediums to react to the attack, making sure public servants were seen as the true heroes of 9/11.

A few years after the attacks, though, Marvel Comics decided to recapture the 1940s sense of comics activism with the release of The Ultimates. Brownstein thinks this project has not aged well, but that it still offers an important example of how comics can still advocate for changes in foreign policy, such as they did during WWII.

Frank Miller’s Holy Terror was discussed as a type of activism that finds its roots in the anger and outrage of 9/11. It’s politics are messy and somewhat misconstrued (um, what? – Ed.), but it offers an honest take from a creator that basically saw the attacks take place just outside the windows of his home. Brownstein mentioned that a lot of comics activism will be rethought and reexamined later on, in hindsight. Things that shock and create controversy know might offer different insights into their messages after time distances them from the events.

Cartoon strips like Doonesbury and Bloom County are back and the Trump presidency is being carefully examined in comics as a way of keeping the conversation going in a media-saturated environment. Brownstein warned that the current state of comics activism is a bit inconsistent and that it might still be finding its north. We are fighting multiple social battles at once and trying to locate a center or central focus to it all proves difficult, but not impossible. There was the suggestion that we do need a point of activist convergence to fight for real change.

The questions posed by Brownstein as he finished the panel should be further discussed in order to create a more coherent line of discourse for activism. What do we advocate with comics? What should activist comics advocate for? Do we advocate for changes in policy? Do advocate for social justice?

Whatever answers these questions yield, comics are there to act the activist consumer products they are to support future causes. Brownstein states, “the key for this type of activism is creativity.” Now it’s up to us to be creative in our activist endeavors, comic book in hand.

Makes me laugh when Comicgaters pine for an imagined past of apolitical comics. Comics have ALWAYS had political and social commentary. And some of it has been quite conservative, as in Gray’s “Little Orphan Annie.”

Comments are closed.