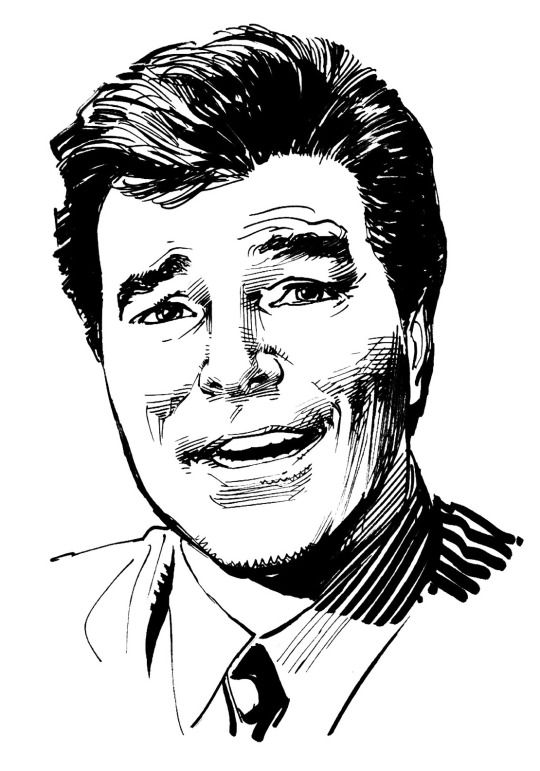

Neal Adams was born in New York City in 1941 and wanted to make comics from a young age, though as he said in numerous interviews, when he started looking for work, the comics industry was in decline. He spent years writing and drawing stories trying to break into one outlet after another, including a parody “Bent Casey” that he drew as a sample for Mad Magazine. As he would tell me years later, Joe Simon said that he didn’t want Adams to ruin his life doing comics.

“There was nobody either five years my junior or five years my senior in the industry,” Adams said in an interview I did with him in 2016. “There are people my age who got into it later, like Jim Steranko and Dennis O’Neil – but people my age were not in comics. I came into this business that older guys who were sad and depressed and assumed that the industry was going to be out of business in a year.”

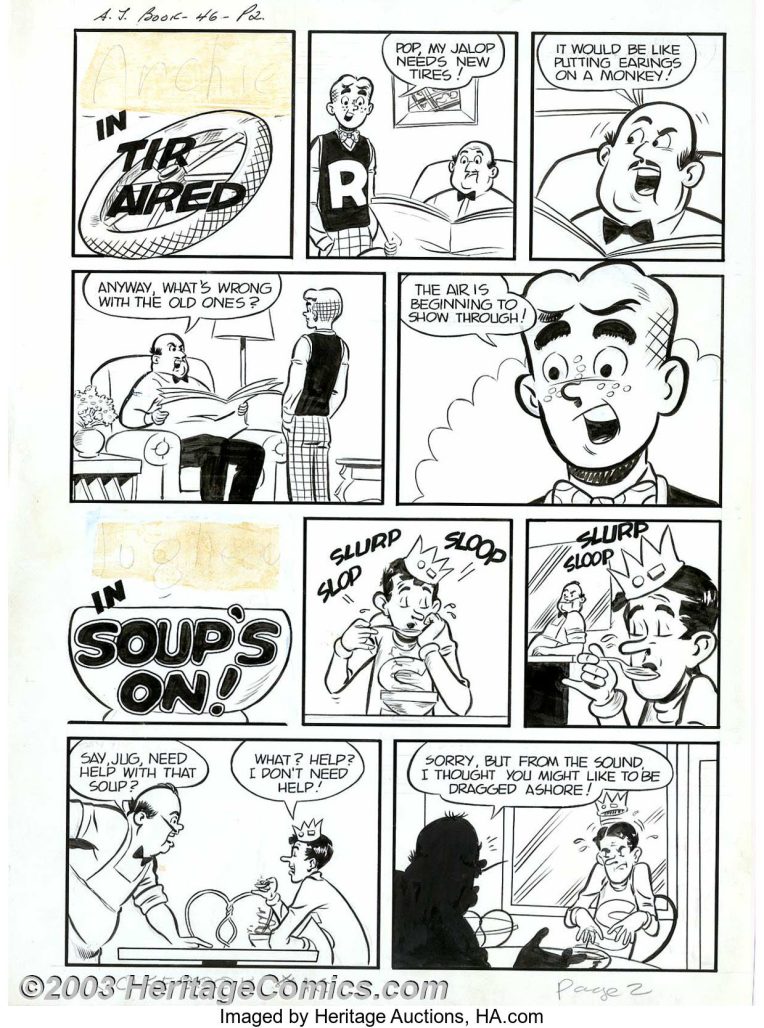

He made short comics for Archie Comics and Boys Life Magazine, he did advertising work, and for three and half years he drew the Ben Casey comic strip, based on the hit television show, which debuted in 1962. “And while I was doing that, I did advertising work because that strip didn’t pay all that well,” Adams said. “I worked seven days a week, 15 hours a day, and I loved it. I just loved it.”

In other words, by the time comic book readers saw Adams’ work in the late sixties, he was already a seasoned professional. More than simply being a good artist and a good storyteller, Adams understood comics and design, he had a sense of color and printing. And although he did work as a ghost for various artists in the sixties – for Stan Drake (The Heart of Juliet Jones), Lou Fine (Peter Scratch), John Prentice (Rip Kirby) and Al Williamson (Secret Agent X-9) – he was working at DC, Marvel and Warren Comics under his own name at a time when it was rare for to be working for companies simultaneously.

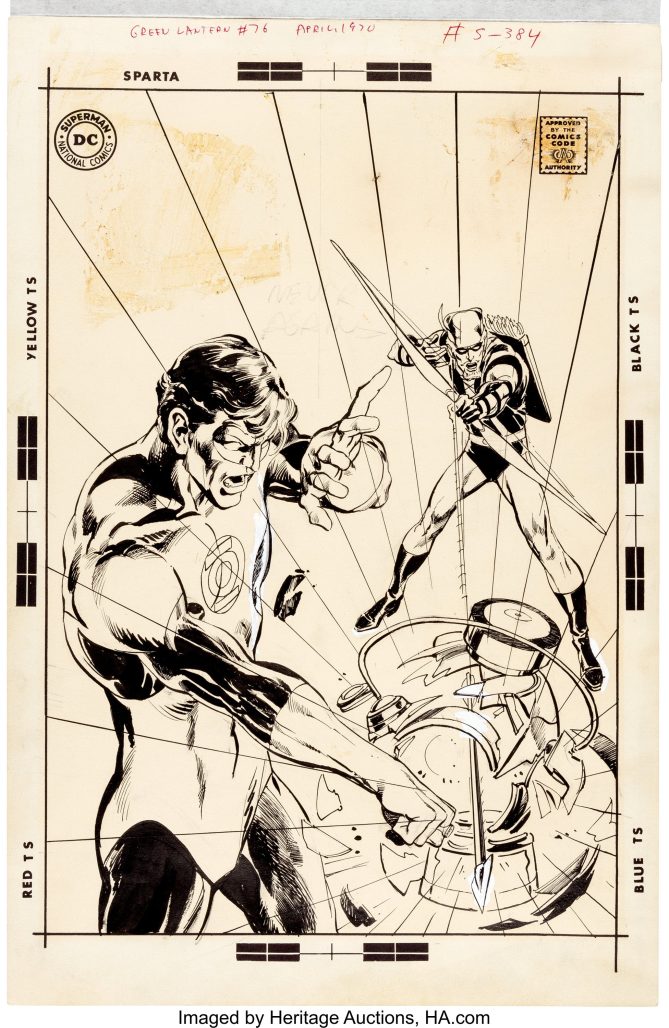

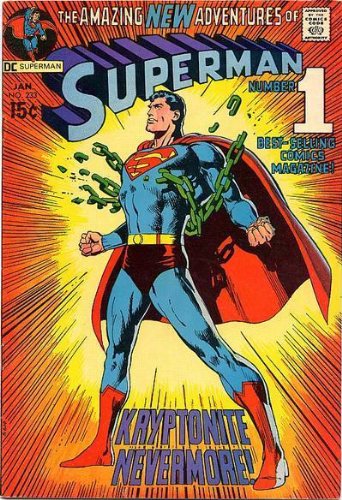

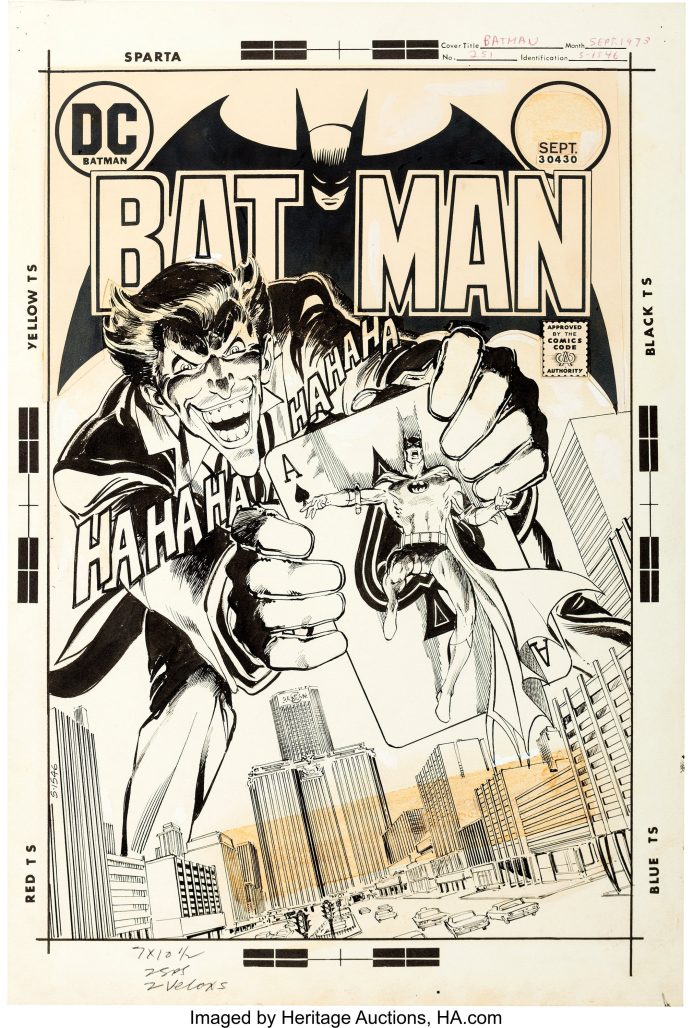

At Warren he contributed to Creepy, Eerie, and Vampirella. At Marvel he drew X-Men and The Avengers, including part of the Kree-Skrull War story. But his biggest legacy is his work at DC Comics. He drew The Adventures of Jerry Lewis and The Adventures of Bob Hope, Our Army at War and The Spectre. Adams wrote and drew Deadman. And beginning in 1970, he worked on Batman and Green Lantern/Green Arrow, primarily with writer Denny O’Neil.

Those stories introduced us to Ra’s al Ghul, Talia al Ghul, and Man-Bat, and for the impact and the influence that those issues had, it’s notable just how few stories Adams drew. He was a prolific cover artist, but he only drew a handful of Batman stories. But in those stories, mostly written by O’Neil, the style and the tone was so sure-footed. It was more than simply a shift from the campy tone of the Adam West TV show, it was a reinvention and a way forward for the character. And a reinvention of the Joker and other villains that affected the tone.

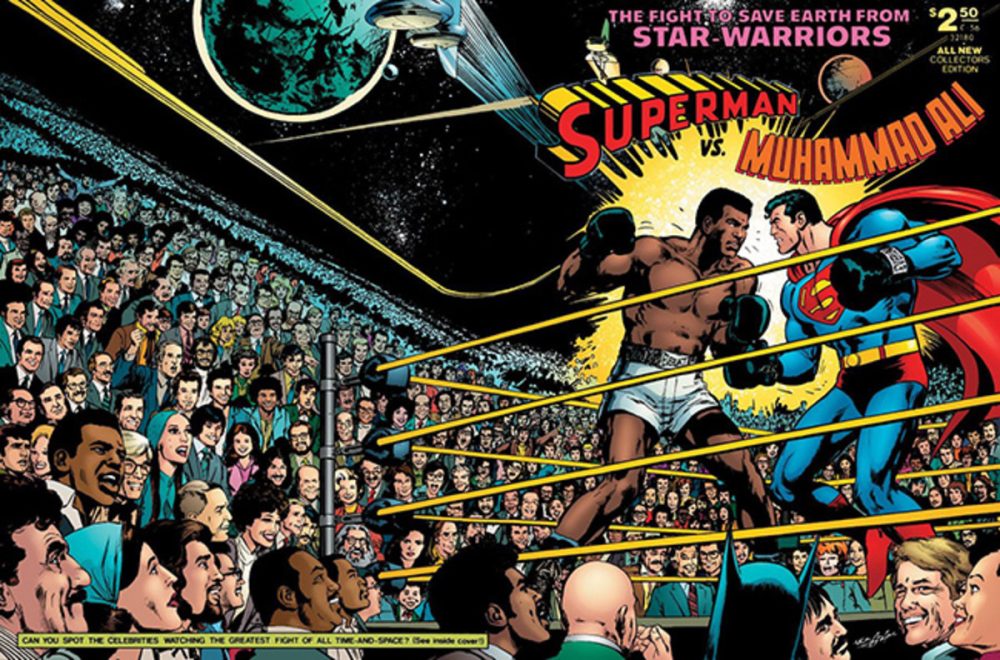

Adams continued to make comics and draw covers throughout the 1970’s, but he ended the decade with his biggest project, co-writing and penciling Superman vs. Muhammed Ali. Today that seems like an unusual – even bizarre – idea for a comic book, but in the 1970s it was even more shocking. “Remember, America didn’t love Ali,” Adams said in 2016. “Half of America hated Ali, but he was a hero to the world.”

Adams and O’Neil teamed up the folk hero Ali with a different kind of folk hero, a costumed superhero created by two young men, the children of Jewish immigrants. And in 1978, Superman and Muhammed Ali could represent not just the United States, but the world in a way that even today stands out. The book was funny and philosophical, featuring iconic images of Superman in space, of Ali as a fighter and a wordsmith. It was a book that had at its spine, a simple but not simplistic set of values. It was about fair play. Which is so simple, and yet, it remains out of reach.

“One may easily think that I did comics for a long time, but starting with, I guess, Elongated Man and ending with Superman vs Muhammad Ali, that was the beginning and end of my comic book career. From that point on I did advertising.”

In 1971, Adams and Dick Giordano founded Continuity Studios, originally Continuity Associates, which focused on not just comics, but storyboarding and advertising work, which continues to this day. “The thing about advertising is that you make more money,” Adams said. “You can put kids through college so they don’t come out with loans. My kids don’t and my grandkids don’t, and advertising paid for that. Comic books probably wouldn’t have. It was a good place to go. You may or may not think so – and I wouldn’t expect anybody to think so.”

Adams could be philosophical like that. “Look, lawyers suck and businessmen suck,” he told me. “I’m sorry. As much as I’m a businessman – and I have to be a businessman – there are moments when I suck. I will have a thought and go, ‘That really sucks. Neal, you’re an asshole, don’t think like that.’ But businessmen think that way. Nothing is gained by not being kind and courteous.”

Adams was a businessman because he had to be, but he was also unafraid of taking on comics companies. It’s easy to say that he had advertising work and other projects that he could fall back on to make a living, but he didn’t fight for himself. He fought for everyone.

Adams’ best known battle on behalf of comics was for Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster to receive credit and compensation for creating one of the biggest pop culture figures in the world. Along with Jerry Robinson and Ed Preiss, they fought for the two to receive credit and compensation as the creators of Superman.

“Finally, truth, justice, and the American Way win out,” Walter Cronkite said on the evening news that night when discussing the settlement.

Adams’ other big fight was over artwork. For years comics companies claimed that they had bought the rights to the art and proceeded to destroy it, give it away, horde it. In the 1970s, copyright laws in the United States changed, and Adams was one of the key people who helped to force companies to act differently. Although as he told the story to me, “it was never a battle. It was always pre-ordained that I would win.”

As he explained it, they didn’t understand copyright because there was a difference between buying a piece of art and buying the reproduction rights. And if they had been buying artwork for fifty years, they had not paid sales taxes on it. “Somebody, sooner or later, is going to go to Albany and visit these people – and when you press that button, it will never be unpressed. Tax people are not like that. They will hound you to your death. The next week, they started to return artwork. I did my homework, and they didn’t.”

I have spoken to many artists over the years who have talked about their contact with Adams when they were young. How people would bring their portfolios to Continuity and Adams would sit down and be merciless in his critique. Many people have talked about the sound effects that Adams would make flipping through pages in ways that they can still hear. But if he saw talent, Adams would pick up the phone and call editors – or in some cases, Jim Shooter, then the Editor-in-Chief of Marvel – to say that he was sending someone over who they needed to meet. That was how Frank Miller, Bill Sienkiewicz and many others got work. Or Adams would say that a person’s art wasn’t there yet, but they showed skill as a letterer and called to find them a gig.

Adams didn’t take a percentage or a fee, or ask for anything in return. How many people can speak of having a mentor like that? How many fields have someone where dozens of people can cite someone doing that?

This is why so many different artists have spoken about their deep debt to Adams as an artist and a mentor and an artistic father and surrogate father, even if it’s been years or decades since they last worked together or spoke. From Frank Miller to Denys Cowan to Bill Sienkiewicz to Larry Hama and so many others. And they were not artistic clones of Adams. All the people I mentioned have their own style and approach, but they all credit Adams with a lot.

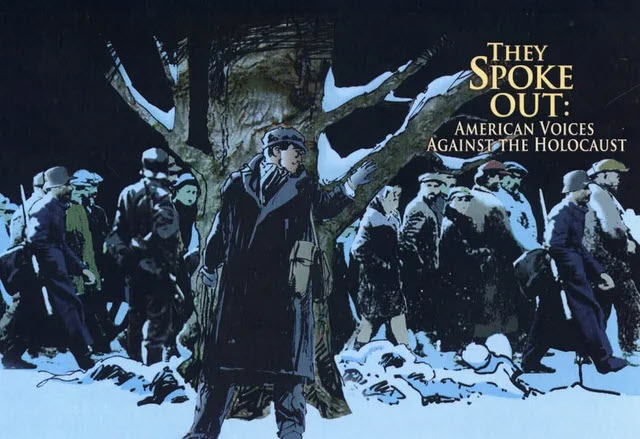

Though his most prominent work was superheroes, Adams did a lot of work on behalf of other artists and suing comics and art for various educational projects. With the David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies, Adams worked to get the government of Poland to return the original artwork of Dina Babbitt. Rafael Medoff, the institute’s director worked with Adams to produce They Spoke Out: American Voices Against the Holocaust which focused on Fiorello La Guardia, Varian Fry, and others who opposed the Nazis and saved lives.

That’s not to say that Adams was always right or that everything he did succeeded. Continuity Comics, which published between 1984 and 1994, was a mixed bag creatively and otherwise. The highlight being Larry Hama and Michael Golden’s Bucky O’Hare, which launched an animated series and toy line. There was mixed response to the more recent comics that Adams wrote and drew like Batman: Odyssey, Deadman, Superman: The Coming of the Supermen, and Batman vs. Ra’s Al Ghul, and his collaborations like First X-Men and Fantastic Four: Antithesis.

He seemed philosophical about that, perhaps because he believed that they would find an audience. He labored over his art. He took great pleasure in it. And while he loved meeting fans, he didn’t draw for fans. He loved art that people hated and hated art that people loved and was unbothered by this.

This is a man who ended up drawing a holiday storyline for the webcomic PVP with Scott Kurtz years ago because his granddaughter. But he liked comics and comics energized him. “This is the greatest time in the history of art,” he said in 2016. “There’s never been a time like this. We can do anything. We can publish it, and a portion of the population will buy it. So we don’t have to satisfy everybody, we can satisfy a niche, and they will buy it and love it. It’s not like rock and roll – it’s better. This is only going to get bigger.”

At a time when some creators expressed a disdain towards cosplayers and many young fans and creators, Adams had a very different response. “Forget Halloween – cosplay,” he said. “I don’t even recognize half the characters anymore, and there’s nothing wrong with that. They love it. It’s a creative community, and it’s coming out of America and it’s going to China and Russia and South America and Australia and all of those cultures have something to contribute to it as well. It’s incredible. This is the greatest cultural explosion in the world.”

Perhaps the greatest compliment that can be given to Adams – and it has been said by those who loved him and hated him – is that comics would be a very different place without him. There are few figures in American comics of whom that can be said. Other than Jack Kirby it’s hard to think of an artist with as much influence. And in terms of his mentorship and stylistic influence, he has few equals. The comics industry and community today is very different from the one he started working in.

I spent half a day at Continuity Studies in 2016 and during one story Adams paused to say, ‘I’ll tell you this, but only if you don’t print it.’ What he told me wasn’t salacious gossip. He wanted to explain what happened, but he also didn’t want to embarrass a friend in print. Or maybe they weren’t friends at that point; I don’t actually know. But he respected the person and wanted me to know that I needed to be respectful. That even if people knew, Adams didn’t want it to be in print.

Of course that required him to trust and respect me, as well, which is not something I forgot. One remembers the people who were nice for no reason. And kinder than they needed to be. I’m also a white cis male and not naïve enough to think that treating me well is a sign that someone is a decent human being. But there is something to be said about someone who makes a point of being kind to others.

Adams was neither quiet nor humble. He knew his worth, or what he thought his work and time was worth, and he would not apologize or exhibit false modesty. Perhaps he got in his own way sometimes, when trying to launch a comics guild or in different negotiations. I don’t know. But he was who he was, and did not apologize.

In our lengthy conversation that day he kept returning to family, to stories of being a father. There was a way in which the studio was an extended family, overseen by his daughter, Kristine, including his other children who work as artists. He loved his work, but he believed that there was more to life than work. That has always stayed with me, and our thoughts are with his family in these days.

There was only one Neal Adams.

May his memory be a blessing.

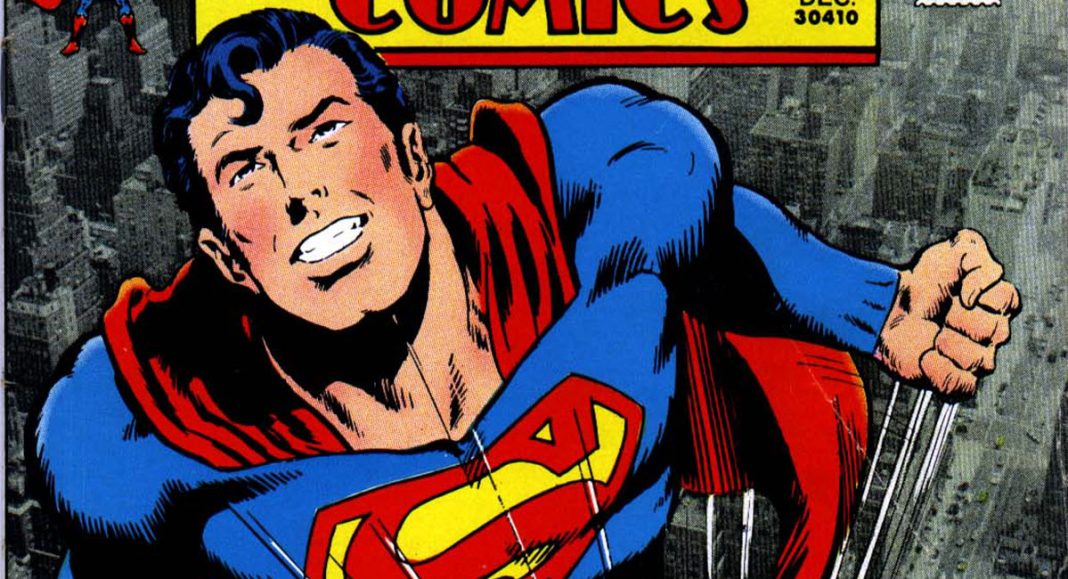

That cover from Action Comics with Superman flying straight up out of the city so impressed me as a kid that I wouldn’t stop staring at it. Couldn’t figure out how the whole thing looked so real, as if there really was a Superman. I don’t have any Neal Adams original art, but I have a numbered print he did of Jor-el with baby Kal-el that came out about the time of the first Christopher Reeve movie. It’s hanging over my head in my office as I type.

Great article on the master!

Comments are closed.