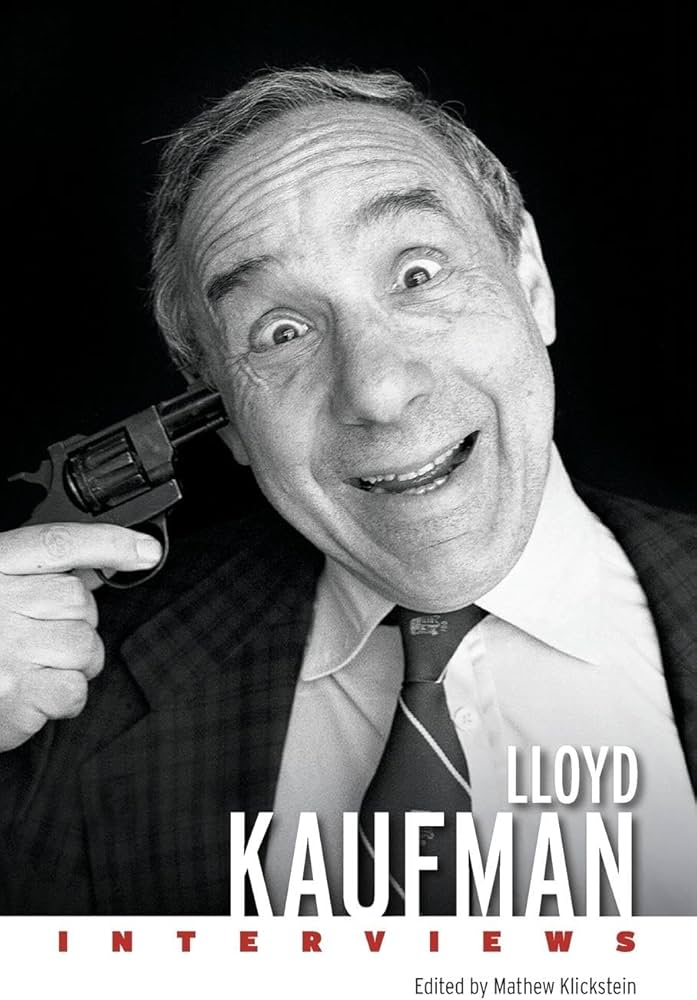

Interviews are entryways into people’s minds. They can pull the curtain back to reveal the mechanics of creative thought and the methods they come up with to bring certain ideas into reality. Few things are as valuable as this for those looking to grow as artists or to expand their worldview. Author and filmmaker Mathew Klickstein has taken upon the task of offering just that with his book Lloyd Kaufman: Interviews (University Press of Mississippi), a journey into the mind of the titular filmmaker through a career’s worth of interviews.

The book is available now and it is perhaps one of the most richly diverse, eclectic, hilarious, and smart collections of interviews in the market. Its scope and the breadth of its themes and discussions all point to a life of legend. As one of the founders of Troma, along with Michael Herz, the producer/screenwriter/director/actor has brought the classic Toxic Avenger series to movie screens along with a host of other projects that don’t conform to the rules of Hollywood or the mainstream on purpose. In a sense, his movies are a statement on non-conformity and the need to rattle the status quo. Kaufman has been the face of Troma, the longest running independent film studio in the world, for more than 50 years now.

Klickstein, a pop culture historian himself, decided now was the time to put together a book made up of some of the best and most insightful interviews Kaufman’s given throughout his life as a visionary creator. Below you’ll find one of them, in full, made specifically for the book. Enjoy.

The following interview was conducted via phone between author Mathew Klickstein and Lloyd Kaufman on June 11, 2023, exclusively for [Lloyd Kaufman: Interviews].

He knew now

Man, he really knew now!

But it was too late

And all he wanted was to make this crowd laugh

Well, they were laughing

But now he knew

— CHARLES MINGUS, “THE CLOWN”

Mathew Klickstein: Let’s start with a simple one. This book is a series of past interviews with you. I’ve been going through them all, and it’s clear you’re always very available for these people who want to talk to you and pick your brain for as long as they need. Sometimes longer. You even talk about how available you are in your books in which you often give out your email for those who might want to contact you. Which begs the question: Do you enjoy being interviewed? Is this fun for you?

Lloyd Kaufman: Certainly. Being a professional narcissist, there’s nothing I like better than talking about myself. But also, we don’t have money for advertisements at Troma. And my partner Michael Herz refuses to go public personally with anything. He doesn’t interact with the public. He doesn’t want publicity for himself. So, as ugly as I am, I have to be the face of Troma.

MK: Despite Michael’s aversion to being personally public, you keep purposely talking about him in your books, while mentioning how much he doesn’t want you to do that.

LK: [Laughs] That’s right. I do.

MK: I have to ask, in All I Need to Know about Filmmaking I Learned from the Toxic Avenger, you also keep talking about your editor on that project, Barry Neville. How much of that was true? Is Barry Neville even a real person, or was that more of a narrative device or a way to seem extra irreverent—you essentially mocking your editor the whole time, while, Troma-style, breaking the fourth wall throughout?

LK: No, he was real! And every time he’d say something, I’d write it down or [coauthor] James [Gunn] would write it down, and we’d put it in the book. Like the paper shortage issue. Barry didn’t want to use up too much paper on our book. “It has to be 353 pages,” he kept saying, “because we don’t want to use up too much paper on this.” The paper was worth more than the book! We made it all sound funnier than it was, but anything we talked about with Barry Neville in the book probably really happened. Really good guy. In fact, we ended up putting him in Terror Firmer.

MK: I find in your interviews a fascinating dichotomy in that you make these movies involving so much graphic violence and sex, and you can of course be extremely vulgar in what you talk about with all these reporters speaking with you… Yet, you also drop in so many references to extremely high-brow, sophisticated art filmmakers or European cinema—Stan Brakhage, Bergman, and their ilk. You’re obviously a very educated, knowledgeable, and articulate person. How much would you say Troma—and you, by proxy, in these interviews—focuses on the “sex and violence” because it’s provocative, compelling, and in many regards commercially viable, and how much is it because you personally really enjoy this kind of smutty, gallows humor posturing?

LK: I have to say that I like all of that stuff. A lot of it is aimed at younger, cutting-edge minds and audiences, too. At the same time, I enjoy interweaving political statements that may get our viewers and the readers of these articles to think a little bit outside of just the naked men and women in my movies or some of the shit talk I’m spouting out in these pieces you’re talking about.

MK: “A spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down”?

LK: Right. I can make some important points about how fucked up everything is in our world on a very important level through saying a lot of the crazy things I say in these interviews. Just as we do the same thing in our movies filled with people getting their heads getting chopped off. Meanwhile, yes, all of our Troma movies are informed by all the top directors. Take Toxie and [love interest] Sarah, the blind girl. That’s Chaplin’s City Lights. Tromaville is also very much Preston Sturges’s fond satire of American villages. In Troma’s War, there’s quite a bit of Sam Fuller and Robert Aldritch. The opening of Terror Firmer is supposed to be a tribute to Fritz Lang’s Glen Ford movie The Big Heat. I could go on and on.

MK: Would you say you’re parodying these films, or are you actually trying to emulate them?

LK: They really are tributes. For example again, I use the song “Shall We Gather at the River” quite a bit, because that was a big theme in many John Ford movies. I do that because I love John Ford and I love that hymn. Truly.

MK: What would you say to those who would think you’re totally fully of shit right now? You’re talking about John Ford and Charlie Chaplin, and meanwhile you’re making films where people’s heads aren’t just getting chopped off—they’re getting smashed by car tires and pulverized by slime-covered mutants.

LK: All I can tell you is that the Museum of Modern Art showed Tromeo & Juliet in their Shakespeare series. It took them thirty years, but they did it. And they also played the world premiere of Return to Nuke ’Em High Volume 1, which is an LGBT movie… that is also filled with the head crushings and all that. And then the Museum of Moving Image played the world premiere of #ShakespearesShitstorm. How do you judge art? It seems our fans like us, and so do museums. In fact, most of the theaters we do get into these days are art house theaters.

MK: A lot of this makes sense, actually, considering many of the filmmakers you talk about having so much admiration for in your interviews tended to have much more acclaim in artistic circles in Europe than in mainstream audiences back here in the States.

LK: Take Jerry Lewis who was in the pantheon of the underground the way that we’ve been decades later. We all know how much he was beloved in France, and that’s true for us, too. They’ve really understood our movies, and the Cinéma Français has done several “seasons of Troma.” So, they get it. Japan gets it. But, we still don’t have distribution in many countries, even though we have a lot of fans thanks to bootlegging and people passing around our films all over the world. We also had so many festivals around Europe selecting and promoting our movies. Spain, Italy, as well as Portugal and all over Scandinavia. That was a while ago, though, back when they would get government subsidies so they could select movies like ours that were truly independent. Now, unfortunately, the economics are not so good, so they have to rely on advertising from the studios who now subsidize what they’re doing instead. It becomes sponsorship from the big studios, and that impacts what movies these festivals are showing now. They’re more likely now to play so-called independent movies from Fox Searchlight and HBO. That’s not really independent. Even Tribeca now plays these $200 million films as their opening features.

MK: That’s definitely been going on for years now, where you have these festivals like Sundance that have basically become marketing posts for films that are already ready to go and don’t really need the publicity the way true indie pictures need who don’t have that same studio, network, or streaming support the way true indies like you guys truly need.

LK: Yes, my daughter is now finishing a documentary called Occupy Cannes all about how Troma was policed out of the festival after supporting the Cannes Film Festival for fifty years. It’ll be a great film but doesn’t exactly show Cannes in a nice light.

MK: Yeah, what the hell is the new Indiana Jones movie doing there right now?

LK: Well, nobody knows about it, so they need the publicity. [Laughs] The filmmakers really need some more exposure.

MK: All joking aside, here you go again—Going back through all of your interviews over the years, you’ve never pulled back from being brutally, balls-out honest in what you’re talking about, even when it comes to naming names and speaking very specifically about those you deem as heroes and villains of the film, media, and political communities. This hasn’t just been recent for you, is what blows my mind. Even in the beginning before Troma and you had something of a cachet, you spoke your mind without any filter at all. You just came right out of the gate talking about “the system” and Hollywood and what you always call “the elites” as soon as you started being interviewed, going all the way back to your earliest, earliest days. That was really shocking to me to see in print. These weren’t simply words of a long-time, jaded filmmaker who had been in it for decades. You were like that in the very beginning, back when you were still in your twenties!

LK: [Laughs] I think a lot of that was because of Grammy Kaufman. My grandma wasn’t a Communist, but she was pretty close to it. And she gave me stuff to read from the time I was very young about people like Castro and anti-Vietnam [War] literature. She supported [activist] David Dellinger and Scott Neering who was a professor at the University of Pennsylvania who got kicked out and blacklisted; many of the kind of agitators of the fifties and sixties. She’d get me to read I. F. Stone’s Weekly. She’d explain why the war was bullshit. And she gave me a book to read, Brave New World, which was not the book you’re thinking of—It was about how great China and Mao were, entering a “brave new world.” Anti-capitalist and all of that. [Laughs] I was so young! Probably read it before I read the “real” Brave New World.

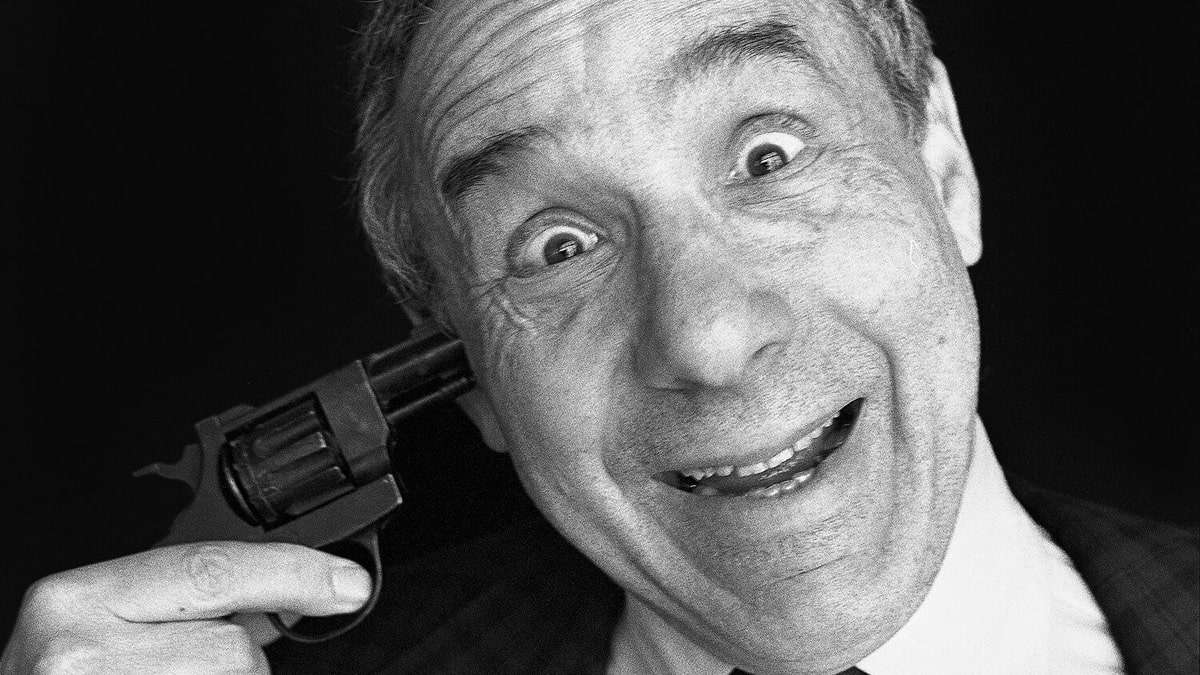

MK: Let’s move on to some of the more entertaining aspects of how you position yourself and Troma. You have this very carnival barker type of strategy, with the bowties and the brightly colored striped suits. It’s so clear what a great performer you are in the interviews you do. You do it very well. But I can’t help but feel that many of the people talking with you are kind of goading you on a little bit, and you react in kind by playing the part, so to speak, of the “wacky Troma president and filmmaker.” Can you talk about that and how, for instance, your wife Pat has said in the past that you’re not really like that in your everyday, domestic life?

LK: Dressing up as a clown is an act to get attention. Wearing a tie, jacket, suit or whatever, I want to respect the film festival or interviewer, too. In the old days, the director would often wear a jacket and suit on set. I never did that, but I thought about it quite a bit. Show respect for the crew, too.

MK: Your typical outfit almost has a kind of Henny Youngman meets used car salesman quality. Like an old vaudevillian or Borscht Belt comic. When I watch some of the videos of your interviews or when I’ve seen you at signings and other promotional events, I almost feel like you’re going to break out with an accordion and a monkey at some point. How did you develop this uniform of a sort over the years?

LK: A lot of it comes from my father. He had a great sense of humor, was genuinely funny. I don’t know that I’m genuinely funny myself. Really, though, it can be an Achilles heel for me, because all of my movies are comedies, and comedies don’t work universally. They’re the most difficult medium. My father used to tell me that a lot, how ill-advised I was to keep making comedies. What’s funny in Ohio is not always funny in Rome. Also, it’s very hard to make people laugh. You can even watch some of the great classic comedies of the twenties and thirties, and some of them are hilarious, but others are too timely and don’t really work anymore, if they ever did. But, I have been very proud of the fact that our movies have a certain timelessness. Look at something like Squeeze Play!, which people are really only now starting to rediscover. It’s a very funny film and has a very good theme to it, namely the underdog quality of women and the ERA, even though it was a raunchy movie about softball with balls getting hit in people’s butts and sex and goofy slapstick. Very entertaining, yet still making an important point. I mean, women still are the underdogs today, almost fifty years after that movie came out. I guess everything we do is about underdogs, though. Take Return to Nuke ’Em High, with the two lesbians who are underdogs in that movie—and yet it’s still a funny movie today. And I imagine it’ll be funny in twenty years. So, who knows. I guess maybe it really does come down to the old Frank Capra quote of him saying that the best causes worth fighting for are the hopeless causes.

MK: Similarly, you in your interviews and certainly in your films are always especially agnostic about the way you attack and mock all sides—the soi-disant right, left, and in between—of so many political angles and issues. You’re exceptionally even-handed in how you dole out the satiric jabs, very much like South Park, created by one of your protégés, Trey Parker.

LK: That was why I loved Cannibal! The Musical right away when I first saw it. It still needed to be finished—they had to shoot a more “Troma-esque” opening before we could really take it on, but they did that and we’ve loved everything Trey and Matt have done ever since, always seeing a bit of Troma in their future projects, too. They’re able to get away with a lot more than we do, though, because South Park is animated, and our projects are live-action. Even though you may see [South Park regular] Kenny getting his arms ripped off the way you might in some of our films.

MK: Even as a kid, when I was growing up with Troma movies on the USA Network and TNT evening programming—Up All Night with Rhonda Shear, and Joe Bob Briggs’s show, etc.—I could tell that you guys were doing something that was very forward-thinking. And nowadays, these many years later, it does indeed seem Troma’s motto, “Movies of the Future,” has been vindicated. So many of the films you’ve made are not only timeless but have proven to be extremely prescient in content, style, and agenda. This includes your pioneering takes on environmentalism in films, vegetarianism, and the fact you guys really were the first to kick off the “sex comedy” craze of the eighties, well before Porky’s and Revenge of the Nerds.

LK: It’s amazing, isn’t it? Take the guys who made the Deadpool movies: There’s no question they were greatly inspired by The Toxic Avenger. They’ve talked about it quite a bit in the past. And of course we’ve got our own James Gunn out there continuing to make movies that are very “Troma-ish.” There’s that new movie that just came out, Renfield, and they have two scenes that are exact copies from Citizen Toxie. The New York Times way-back-when said the filmmakers behind RoboCop clearly looked at The Toxic Avenger, too.

MK: What do you think changed for Troma? There was a point, as you’ve said numerous times before, when you guys were making some decent money, or at least would get your investors paid back or could get enough money to make more films more quickly. When did that change to how it’s become for you over the past few years where it’s nearly impossible to get funding for a Troma film?

LK: Well, I think it really started up right as we began breaking out, ironically enough. When Reagan became president in the eighties, he got rid of the consent decree of 1948.1 This meant, among other things, that studios could now own theaters again the way they did before 1948. This also led to the theaters all merging into an extremely small handful of chains. Which was not, in the long run, very smart. Because, today, they’re all going bankrupt. Oligopoly doesn’t work. You need competition to create innovation. And the Powers That Be don’t want competition. We’ve always seen this whenever there’s any new technology. The oligopolies want to screw it all up unless or until they can take it over. Which is what they’ve always done and which is what they’re doing now with AI. What they’ve done with the internet. Look what happened with Blockbuster—they took over the video market, they got rid of all competition, there was no longer any innovation, and the people running it couldn’t keep it going, and it went out of business. And it took down the entire video market, which independents like us—real independents—needed to keep us afloat. We lost the independent theaters, we lost the video market, and now we can barely even play in the online world. Streaming? Forget about it. They don’t want us, but they’re in charge, so they can do whatever they want. Which makes life very difficult for Troma and all the other true independents like us. Look at airlines: no competition, so there’s no amenities and no innovation. The experience has become horrible. No one likes to fly anymore. But then you look at hotels, and there’s plenty of competition there, so they have to innovate with better and better comforts and amenities and innovation to get people to come to their locations over all the other ones that exist. There it is right there.

MK: What you’ve said here about streaming services and the internet is interesting, I think, because a lot of people would believe these online portals and opportunities would be a big help to companies like Troma.

LK: Well, without a doubt, streaming has been helpful to us in some ways, actually. We have our own streaming service, of course—Troma NOW—which is small but is working. It’s probably the only profitable streaming service on the face of the globe. And it’s great, too! No advertising aside from me being a clown. Lots and lots of great movies, too. Even movies we’ve been acquiring like Robert Downey Sr.’s Putney Swope, and Dynamite Chicken with the guy who burned himself up—

MK: Richard Pryor?

LK: Yes! Hilarious guy. It’s a terrific film. And also all these films by new people, all the James Gunn’s of the future. Like Mercedes [The] Muse’s very feminist, experimental, and crazy movie Divide & Conquer. Men will be shocked, but women will understand. It’s a wonderful film. There’s all sorts of great stuff we’ve been getting, not to mention all of our own classics. All of this without any advertising aside from me doing my little videos and live events, and word-ofmouth through our fans. So, yes, the streaming has helped us, without a doubt. It’s helped us to connect and reconnect with those people who may not know who we are or watched us maybe when they were younger and are now coming back to remembering all of our great movies that have also influenced, as you’ve been saying and as we know, so many of the current generations of filmmakers, too.

MK: This is actually something I was talking with your assistant Garrett about when we were all together at our book signing2 a few weeks ago: It’s the idea that John Cassavetes used to say that everyone wanted to make movies like him, but nobody wanted to help him make more movies. You had something similar going on with Kubrick, too. Everyone respected him and wanted to emulate him, and yet he had so much trouble toward the end making the movies he wanted to make.

With you, we have now an entire generation—or maybe two or even three at this point—of extremely successful filmmakers who say they got their start with Troma or were greatly inspired by Troma films… and yet, if we’re being honest, a lot of the general public would have no idea who you are or even what Troma is. How do you reconcile this dichotomy?

LK: That’s a very good point. [Laughs] I don’t really know what to say. The problem is we’ve never been able to advertise, so we just end up getting steamrolled. It’s very unfair. Especially when it comes to certain filmmakers who go so far as to trade on our name or who are blatantly ripping us off. They know they can get away with it, because people know who they are and don’t know who we are. And the other problem too is that our movies don’t make any money anyway, because we’re economically blacklisted. There’s no way for us to get deals on Amazon and those kinds of places. Those streaming services are worse than terrible. Or they want to censor us. So, there’s no money to be made there. Netflix and all that stuff. If I direct a movie and I go there with a suitcase full of merch like Willy Loman, they’ll play the movie maybe. But only for one or two nights. In New York, maybe we get a couple of weeks. In LA, maybe a couple of weeks. But the rest of the country? Maybe one or two nights or a midnight screening or something. I enjoy meeting the fans and all that, but I’m seventy-seven years old and it’s getting to be a bit much. I can’t keep carrying everything all over the place anymore! We’re just not making any money, which means I can’t tell people that if they put their money into Troma you’ll make money. Twenty years ago, our movies would make money—quite a bit of money, or the worst that would happen would be that after two years, there’d be a small profit at least. Today, though, you invest in Troma, and you’ll lose money. As good as they are—and they’re even better today than ever! Take #ShakespearesShitstorm. My wife and I had to put up all the money for it ourselves—with a little help from a company called Bad Dragon, which I suppose you could call the “General Motors of dildos.” They paid for about 15 percent of the film, really as patrons, as fans. But we haven’t been able to make any money off of it yet. Nothing. Nobody wants it. We only got it in one film festival, but they weren’t able to get any media traction on it namely because of the title. And the Museum of Modern Art didn’t want it due to the content, which was too much for them this time around. And it’s a shame, because it really is my best movie yet, and my most personal. People will get it in twenty-five or thirty years. But, I won’t be around by then!

MK: Dour! Can’t you leave us with some light at the end of the tunnel here for what may very well be your last interview ever since you’re edging so very close to, as you often say, making a sound like a frog?

LK: Look, Troma has a life of its own. And Michael Herz is younger, too. As I become more infirm and demented, he’s in great physical and mental shape. So, I think it has a fair amount of time ahead under his leadership. But the company has got some very valuable properties that in the right hands could make quite a bit of money. Sgt. Kabukiman has already been optioned twice by Legendary to become a series; people all over the place want to do things with Poultrygeist. With some money behind it, the Troma brand name could be very, very successful. It’s worldwide known. You can look at my Twitter feed, and people think we’re doing great! Troma does have a life of its own. And then there’s the fact that, though I’ve urged her not to, my oldest daughter has been considering taking the reins once my two grand-monsters get past high school. Which won’t be too long.

Notes:

-

As ruled by the landmark Supreme Court case United States v. Paramount Pictures Inc., the consent decree essentially broke up the monopolies major studies had over the entirety of the Hollywood film system, disallowing ownership of theaters by studios (for example) and creating other crucial policies that would allow not only more independent fare but foreign films to be exhibited and marketed more easily in the United States. Indeed, the ruling is also known as “Hollywood Antitrust Case of 1948.” This was systematically reversed by President Ronald Reagan and, later, by President Bill Clinton during their respective tenures, particularly via Clinton’s Telecommunications Act of 1996.

-

Kaufman took part in Klickstein’s 2022 book See You at San Diego: An Oral History of Comic-Con, Fandom, and the Triumph of Geek Culture.