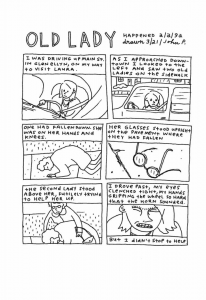

To gaze upon a page of King-Cat is to see the comics form stripped out to its basic element. There on the page, one can see the direct connection between the artist’s mind, his pen, his heart, and the piece of paper that acts as the conduit to all of these elements. John Porcellino, the auteur of the visionary King-Cat comics zine, is a master of the form. His genius comes from the deceptively unpretentious nature of his work. The black and white drawings, the irregular squares of his panels, and his deep, often painful subject matter all coalesce to display singular comics craftsmanship of the highest order.

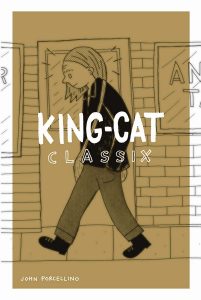

The early years of the King-Cat zine are newly collected by Drawn + Quarterly in King-Cat Classix. The collection offers readers the opportunity to see a budding artist dabble in different styles, genres, and tones before their eyes. With selections from the first fifty issues, King-Cat Classix is, in many ways, a revelation and a rosetta stone. The DIY aesthetic of the early 1990s is at full power in the pages of this volume. And now, reading some of these stories some thirty years later, King-Cat shows us the remnants of a different world; a world pre-Internet, pre-social media, pre-conspiracy theories in your face 24/7.

I had the opportunity to chat with Porcellino about the re-issue of King-Cat Classix. I started our interview by asking about the process to look back and what it felt like to see the early years of one’s life project.

AJ FROST: I wanted to talk to you today about the re-issue of your King-Cat Classix collection. Before you began the process of re-issuing select strips from your archive, did you often go back to look at your early strips? What do you feel when you look back on your early work?

JOHN PORCELLINO: When I was younger and had just started working on King-Cat, I would read and reread my work a lot… it helped me figure out what worked and what didn’t and gave me the chance to try to figure out why. I was basically teaching myself to make comics. I learned by doing it and making mistakes, or even “happy accidents” that I could investigate and grow from.

Nowadays I don’t read my own comics. I read through them while I’m making them of course, and then go through each new issue before it goes to press to look for last minute edits or typos etc. But once the work is published I don’t really go back to it.

When I do look at my early work, I feel mostly satisfied. I never worried about making a “perfect” comic. I always let each new comic be what it was trying to be without worrying too much, and just moved forward. So each comic sits in its own space. At every moment I just tried to be honest, so I accept that my old stuff, whether it’s good or bad, refined or sloppy etc., was coming from the heart, and I accept that about the work.

FROST: What do you remember about those first issues of King-Cat? When you think back on them now, where does your memory transport you to? How do they make you feel?

PORCELLINO: It was a time when anything was OK to explore. I tried all kinds of different things. There were no rules to comics, you could do anything, so there was a feeling of freedom. I had no audience, so I was just making comics for myself and a few friends here and there. I printed 18 copies of each new issue. It wasn’t a big deal. It felt good to always be working and stack up the finished pages.

I can picture where I was when I drew the comics… usually in DeKalb sitting in my bedroom, at my grandmother’s old kitchen table. This round formica table in the corner of the room, with an old red lamp that I garbage picked. So the whole room was bathed in this warm red glow. Playing music in the background and getting ink all over my hands.

FROST: I think that the appeal of King-Cat Comix (at least for me) stems from its raw and unflinching aesthetic. The reader feels so connected because these are stories not produced by a system. How do you feel your art connects to readers? Or do you not care about that aspect of the process?

PORCELLINO: It took a while to realize an audience of readers had built up around King-Cat. I went 40 issues before I noticed. At that point (1994) me and my friends Mr. Mike and Zak made a trip up the west coast and met a lot of our penpals from the zine and comix communities — Julie Doucet, Tom Hart, David Lasky, Jon Lewis, Megan Kelso, lots more. At the time Seattle was the center of the underground comics world, and we came in like hayseeds. I didn’t realize until that time that there were so many other people who thought seriously about comics as art. It was eye-opening and kind of intimidating. When I went home and started to draw it was the first time I realized people would read and judge the work I was doing. It kind of froze me up for a while.

Now, having done King-Cat for so long, it’s beautiful to see the kind of community that has grown up alongside it. I have readers who began reading King-Cat in their teens who now have kids in college. Really, what I wanted most from art was a way to connect with people, and it’s succeeded beyond my wildest ideas.

FROST: Your stories range from ribald to romantic, meditative to manic. As an artist, how do you choose to you follow your muse? Do you feel that working quickly is the best way to capture the essence of your intentions? Or does slowing down feel better when producing such personal work?

PORCELLINO: Either way works, depending on what the story wants. Some stories need to be labored over, to be developed over time, refined, discarded, come back to, reworked, discarded again etc until they’re ripe and ready to pick. Other stories fall right out of you onto the page and have an energy and a spontaneity that would be killed by reworking them. The trick is learning which is which. It takes time and practice and a self-critical sensibility.

FROST: Do you agree that your work is “punk?” Are labels too limiting?

PORCELLINO: Labels are limiting, but they can also be important guides for people. I don’t worry about it too much.

My work is punk in the sense that it’s a way of engaging with the world in an honest, direct way; of looking at things with open eyes, not sugarcoating things or making them worse than they are, but really confronting the essence of things and wrestling with that, and then making some kind of art out of it that you can share.

I grew up in punk, but I always had a very broad view of it. To me, punk is less a form of music and more a lens through which to view the world. It’s a map that helps you navigate your life. In that way, punk can help you no matter where you are or what you’re doing. It’s a way of living in the world with autonomy.

PORCELLINO: If you mean will people always be creating independent art and sharing it with others, and will there be people looking for independent art, attracted to it, and transformed by it, then yes. Right here in 2021, the most unorthodox, groundbreaking stuff is in the underground. There’s a powerful energy in the self-published comics community. It ebbs and flows like anything, but it doesn’t go away. The more commodified the world gets, the more big companies look to train generations of consumers to enjoy being spoonfed pap, the more people will resist that and look for ways to make their lives more personally meaningful. That’s where real art can make a big impact. It’s happening right now, all over the world, as we speak.

FROST: In your opinion, what is the future of the zine? We are long past the golden age, right? Does the zine have a future as a physical piece of media? Or has all the underground art simply moved online?

PORCELLINO: I’ve been doing this long enough to know that the Zine World is like a wave, rolling in and then rolling out. It gets more powerful, and then it recedes a bit and comes back. Right now it’s a Golden Age of self-published comics, similar to the 90’s. You have some of the greatest cartoonists working today self-publishing their stuff in various formats.

A lot of the energy in zines migrated online when the internet took off. Of course, the ‘net was easier, cheaper (in a way), the potential was seemingly unlimited, so it makes sense. The internet is good for a lot of things. But what happened was maybe there were fewer print zines being produced, but the quality of those zines went way up. The people left making print media were invested in the very idea of print, of the tactile quality of holding a work of art in your hands, of the very personal interaction zines can engender.

Look around at some of the zine calendars online… Zine Festivals have sprung up all over the world. Every mid-sized city in the US seems to have one now.

FROST: How would you compare the work found in the first fifty issues of King-Cat to the work that you create now? Did you see any change in your attitude towards the work?

PORCELLINO: It’s different in many ways, mostly surface details — things now are more refined, more painstaking. I work a lot behind the scenes before I start drawing a comic, so there’s less slinging ink for slinging ink’s sake — but at its core, I think it’s stayed more similar than it has become different. It has always been about expressing myself openly, and honestly, as honestly as I can. Looking at small moments and digging into them to see what’s really there. Examining things and learning.

When I first started King-Cat, it was with the idea that it would be an open enough forum that it could change as I myself changed. As I grew, it could grow. It could always reflect what was going on at the time… what my interests were, where my head was at. So, I think the formal aspects of it changed — I expected and encouraged that — but the essence has stayed the same.

King-Cat Classix by John Porcellino is available today, February 9, 2021, from Drawn + Quarterly. Follow John on Twitter and Instagram.

Great interview with a great cartoonist.

Comments are closed.