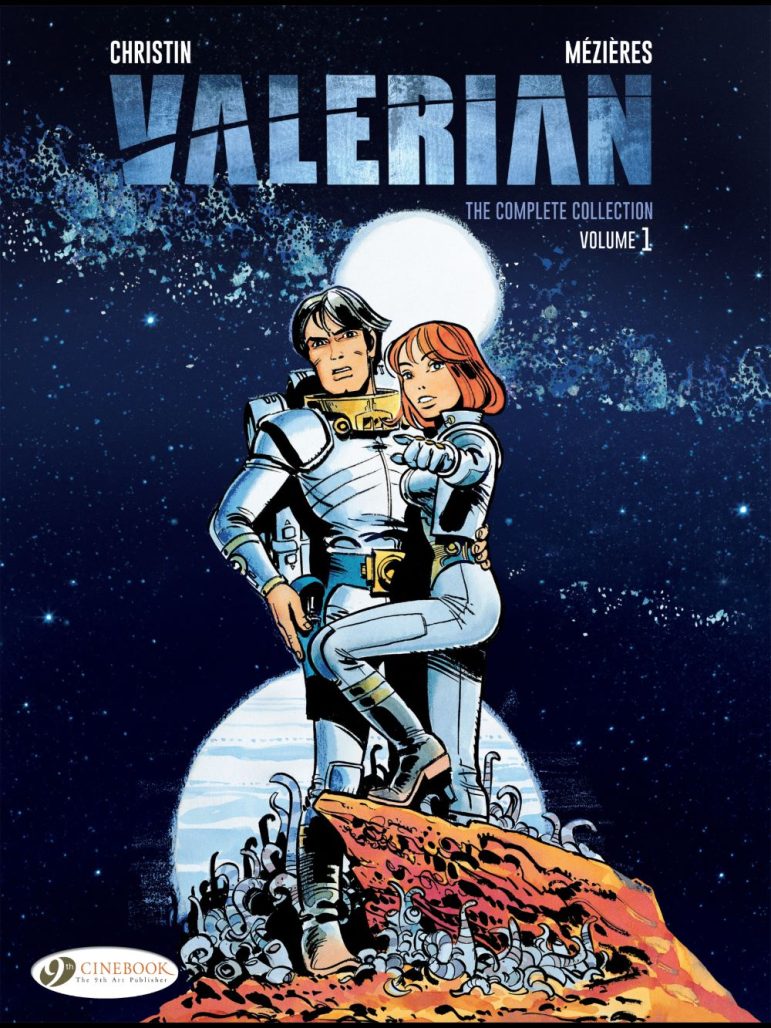

Over the weekend influential French artist Jean-Claude Mézières passed away, aged 83. While his work is relatively obscure to American audiences, the DNA of his imaginative work on the long-running Valerian and Laureline series made their way into American cinema, and the comic remains a classic in the European bande dessinée canon.

As Le Monde wrote [translated by DeepL]:

“Rarely has a French comic book author inspired so much cinema, especially American cinema. Without his innate sense of direction, science fiction would never have become such a fertile genre within the 9th art.”

Born September 23, 1938, Mézières grew up in the Paris suburbs and first met his lifelong friend and eventual Valerian collaborator Pierre Christin at a very young age – in an air raid shelter during the Second World War. Inspired by his older brother and the comic strips of his youth, the young Mézières pursued illustration as a vocation. At age 13 he was published for the first time, in French newspaper, Le Figaro’s children’s newspaper, and age 15 he joined the Institute for Applied Arts in Paris for four years. Among his classmates were Patrick (Pat) Mallet and a young Jean Giraud (later to be internationally known as Moebius). Classmates Giraud and Mézières would develop a lasting friendship built on the basis of a shared love of comics, science fiction and westerns. Christin coincidentally attended the high school nearby and Giraud, Christin and Mézières would travel by subway together.

“In spite of his training in the applied arts in 1950s Paris, it wouldn’t be through wallpaper designs that Jean-Claude Mézières would make his name. It was actually his childhood passion for comic books that would be the guiding light of his career.”

Following military service, which included a period in Algeria, Mézières briefly worked as an illustrator on publisher Hachette’s short lived History of Civilization books. When the project folded, Mézières managed to find his feet by forming an art studio with Benoit Gillain, son of Belgian artist Jijé, in 1963 – via the introduction of his friend Giraud. At the studio, he would fill varied roles: illustrator, photographer, model maker, and graphic designer – primarily for advertising.

Fascinated by imagery of the Wild West and the America seen on the cinema screen, Mézières had wanted to travel there for some time. In 1965, age 27, he got his wish – through a friend of Gillain’s father, Mézières secured a working visa for a factory in Houston, Texas. He didn’t reach the factory, instead spending a period travelling and hitchhiking across the USA. With funds running out and his visa only permitting work at the factory, he reached out to old friend Pierre Christin, who had gone into academia and was at the time working as a professor of French literature at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

Christin gave him a place to crash and helped him secure work as an illustrator for a local advertising agency and a Mormon kids magazine Children’s Friend. He also sold photographs from his travels and got to work on a ranch, fulfilling his childhood cowboy dreams. Salt Lake City was also the place where Mézières met his future wife, who at the time was a student of Christin.

*

…[S]oon it was winter, and in winter, there was this high snow, and in the mountains there was no real work to do. I certainly had no money, and Pierre was saying, “Why don’t you go back to comic strips? Because that’s the thing you know the Best.”

Mézières, in a 1986 Comics Journal interview with Gary Groth and Gil Kane (published TCJ #260, May-June 2004)

*

With the limits of his visa being reached, and ranch-work dried up, Mézières and Christin collaborated on a short comic strip Le Rhum du Punch [Rum Punch]. A copy was sent to old friend Giraud who at the time was working on comic western Blueberry for the highly influential children’s magazine Pilote. Giraud showed it to his editor René Goscinny (of Asterix and Lucky Luke fame, also published in Pilote). Rum Punch was published in the March 24, 1966 issue. Another collaboration was also published in July 1966. The money from these strips helped pay for Mézières flight home.

Returned from the US, Mézières went to the Pilote offices seeking work and got his first job on a serialised comic strip, L’extraordinaire et Troublante Aventure de Mr. August Faust [The Extraordinary and Troubling Adventure of Mr August Faust] but found the scripts provided by collaborator Fred to be highly restrictive.

A chance meeting with Christin, who had returned to France, led to them seriously discussing collaborating once more – but instead of doing a Western (since there was already plenty of competition from Giraud’s Blueberry, Goscinny’s Lucky Luke etc), Christin suggested they do science fiction. They pitched a strip to Pilote and Goscinny gave the green light. The first strip: Les Mauvais Rêves [Bad Dreams] introduced the characters and world that would define the rest of his artistic life: Valerian and Laureline.

Bad Dreams began in the November 9, 1967 issue of Pilote and ran for 15 issues. Subsequent series (and collected albums) quickly followed, under the title Valérian, or Valérian et Laureline.

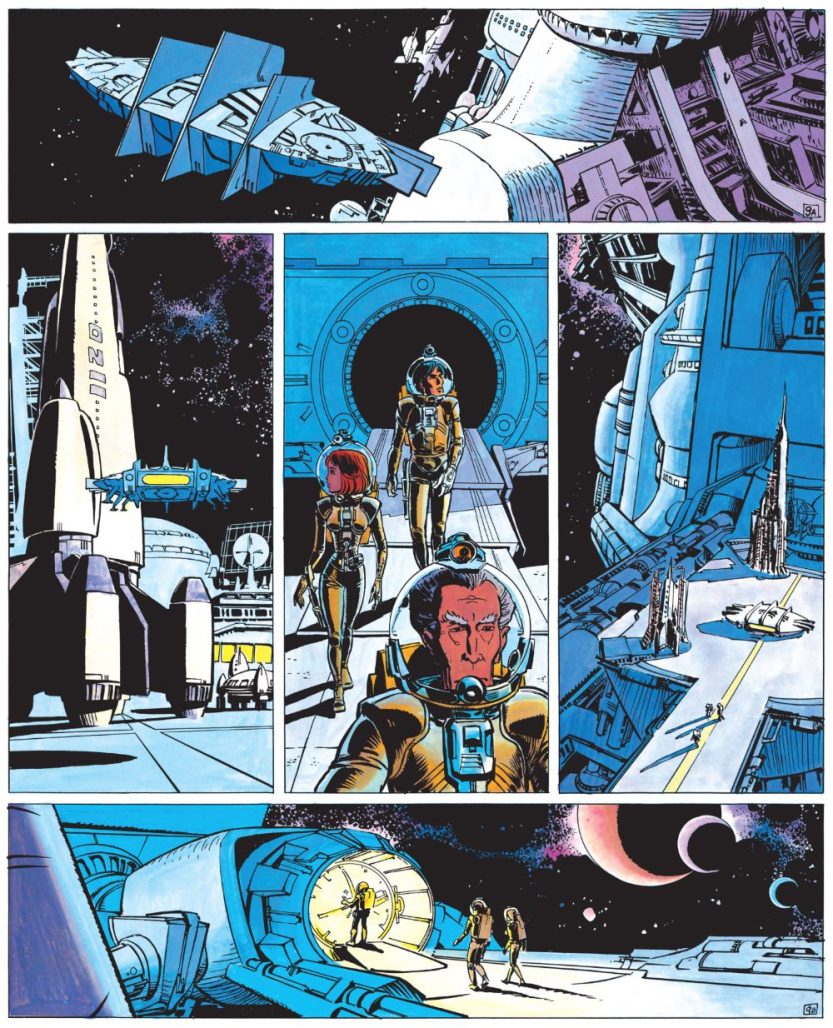

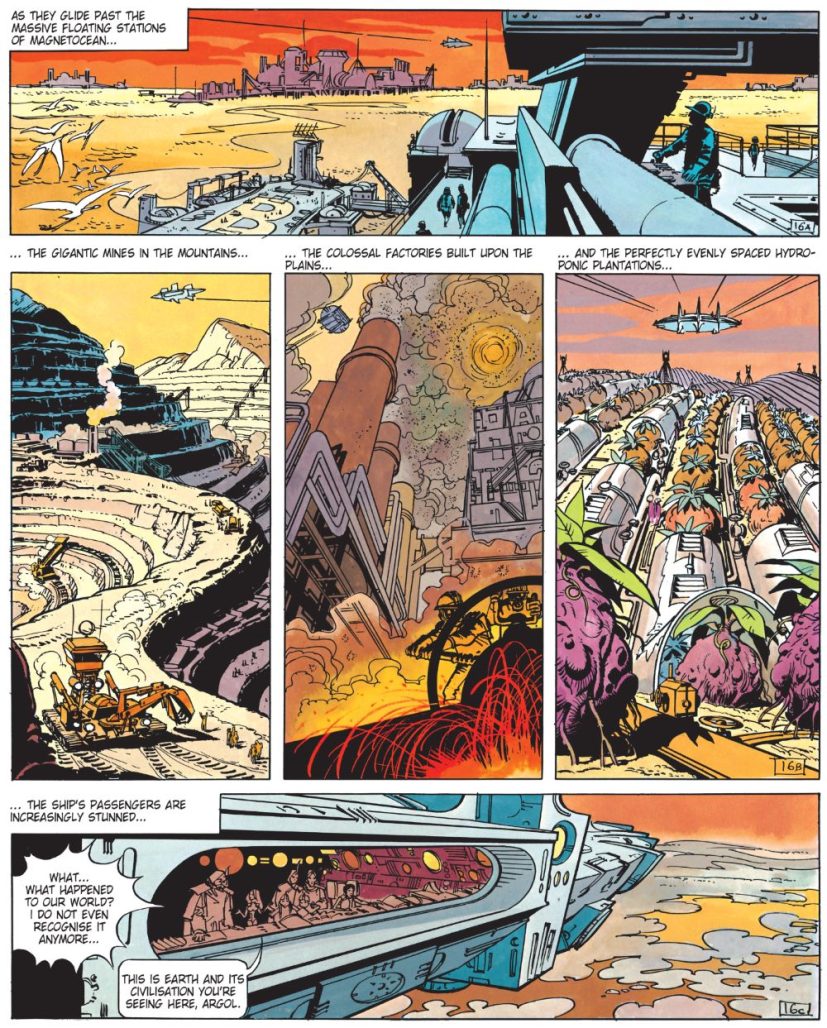

Set in the 28th Century, Valerian and his partner Laureline act as ‘spatio-temporal agents’ bent on protecting time and space from mischief and malfeasance. The debut storyline Les Mauvais Rêves [Bad Dreams] features the first meeting of Valerian and Laureline and the subsequent storyline La Cité des Eaux Mouvantes [The City of Shifting Waters] was the first to be published in collected album format, in 1970 (Bad Dreams had to wait until 1983 for a collection). With such a simple premise every story could take place in any time or any place, giving Mézières and Christin a perfect creative vehicle to pursue their interests and fancies. 24 albums were produced by the pair for publisher Dargaud before the series officially concluded in 2010.

The characterisation of Valerian as the cool, collected – if often clueless – male hero stereotype, and the smart and capable Laureline proved a hit at a time when women’s rights and liberation movements were gaining traction.

Mézières’ incredibly immersive visuals in Valerian coupled with the pair’s inventiveness, helped establish the potential mainstream success of science fiction as a genre in Francophone comics. Alongside 60s contemporaries Philippe Druillet (Lone Sloane, also published in Pilote) and Eddy Paape (with writer Greg’s Luc Orient, published in weekly Tintin magazine), together this work set the stage for the ground-breaking anthology Métal Hurlant in 1974. His participation in such a transformative period of Franco-Belgian comics – a time that elevated the medium from overlooked children’s fodder to what is today described as the ‘9th Art’ was not lost on him.

TCJ interview:

Goscinny started Pilote in 1959, and the beginning of the revolution in comics started when I just came back from the United States. I think in ’65, ’66. I was like a surfer on the top of the wave. I was part of it, really lucky. People were doing what they wanted to do

The partnership between Mézières and old friend Pierre Christin was important to him. While Christin was able to work with other artists and other books, Mézières – who had tried to work with other writers – only found their pairing to truly fit. Besides the Valerian series they produced Lady Polaris, in 1987. One of the rare times that Mézières and Christin departed from their long-running science fiction series.

The TCJ interview, again:

Mézières: There’s one thing for sure. I work with Christin. I don’t think I would be able to work with somebody else.

Groth: On Valerian

Mézières: On anything…It’s either Christin or nobody.

Valerian and Laureline have been translated into many languages. In English it has been released haphazardly. In 1981 the seventh Valerian story, Ambassador of the Shadows was serialised in Heavy Metal. Three other stories were released in English by Dargaud USA between 1981-1984. After other faltering attempts at releasing the series in English, the most comprehensive one finally came in the 2010s when UK-based publisher Cinebook began translating and releasing the series in individual album softcovers and later hardcover collections to coincide with the 2017 Luc Besson film Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets.

The series has proved incredibly influential with its visual DNA making it into Star Wars, 1982’s Conan The Barbarian, and The Fifth Element (the latter of which Mézières worked as a concept artist).

Mézières work was acclaimed and respected in his lifetime. He won numerous awards, including the Grand Prix at Angoulême in 1984 and an Inkpot award at San Diego Comic Con in 2006.

He seldom deviated from working on Valerian and when one thinks of him, one instantly thinks of the series and every gloriously realised page, and Mézières seemed to appreciate this and his achievement from it. In an interview with Ligne Claire in September 2021, on the release of a career spanning art book, the interviewer says [translated by DeepL]:

Interviewer: What will be remembered above all else is Valerian?

Mézières: My only comic book and that is enough.

*

Jean-Claude Mézières

September 23, 1938 – January 23, 2022

For More:

- Pierre Christin and Jean-Claude Mézières discussed Valerian with Paul Gravett at the Institut Français, London, in 2017. A recording can be found here.

- An interview with The Comics Journal was published in 2004 and is available in their digital archives (but is behind a paywall)

- Mézières sketches his characters:

He was not only an incredibly talented artist, he was a real gentleman. Charming and fascinating. This is such sad news.

Comments are closed.